Читать книгу A Decolonial Ecology - Malcom Ferdinand - Страница 15

A modern tempest

ОглавлениеAn angry red covers the sky, the waves are rough, the water is rising, the birds are panicking. Swirling winds wrap around the destruction of the Earth’s ecosystems, the enslavement of non-humans, as well as wars, social inequality, racial discrimination, and the domination of women. The sixth mass extinction of species is underway, chemical pollution is percolating into aquifers and umbilical cords, climate change is accelerating, and global justice remains iniquitous. Violence spreads through the crew, chained bodies are thrown overboard, sinking into the marine abyss, while brown hands search for hope. The skies thunder loudly: the world-ship is in the midst of a modern tempest. In the face of this storm, which finds horizons hidden behind the clouds, vision blurred by the salty waters, and cries covered up by unjust gusts, what course can be taken?

This book seeks to chart a new course through the conceptual sea of the Caribbean. For the Europeans of the sixteenth century, the word “Caribbean,” being the name of the first inhabitants of the archipelago, meant savages and cannibals.2 Like the character Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, “Caribbean” would refer to an entity devoid of reason. The inspection of this entity by waves of European colonization and their sciences would bring forth economic profits and objective knowledge. This colonial perspective persists today in the touristic representation of the Caribbean as a place where one can take a break on the beach without people and offside to the world. To think ecology from the perspective of the Caribbean world is a reversal of this touristic perspective, driven by the conviction that Caribbean men and women speak, act, and think about the world and inhabit the Earth.3

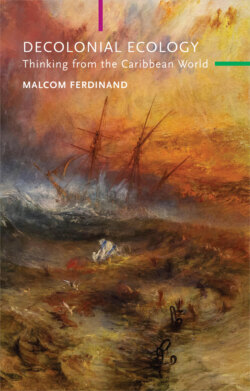

Many rushed to Noah’s Ark when the ecological flood was announced, with little concern for those abandoned at the dock or those enslaved within the ship. In the face of the ecological storm, saving “humanity” or “civilization” would require leaving the world ashore. This desolating perspective is revealed by the slave ship Zong off the coast of Jamaica in 1781, painted by William Turner and found on the cover of this book. At the mere thought of the storm, some are chained below deck and others are thrown overboard. Environmental collapse does not impact everyone equally and does not negate the varied social and political collapse already underway. A double fracture lingers between those who fear the ecological tempest on the horizon and those who were denied the bridge of justice long before the first gusts of wind. As the eye of the storm, the Caribbean makes it necessary to understand the storm from the perspective of modernity’s hold. Through the Caribbean’s Creole imaginary of resistance and its experiences of (post)colonial struggles, the Caribbean allows for a conceptualization of the ecological crisis that is embedded within the search for a world free of its slavery, its social violence, and its political injustice: a decolonial ecology. This decolonial ecology is a path charted aboard the world-ship towards the horizon of a common world, towards what I call a worldly-ecology. Three philosophical propositions guide the way.