Читать книгу A Decolonial Ecology - Malcom Ferdinand - Страница 18

A world-ship: the world as a horizon for ecology

ОглавлениеThe third proposition is to posit the world as ecology’s starting point and horizon. In this, I follow the intuitions of Hannah Arendt, André Gorz, and Étienne Tassin, for whom nature, its defence, and the ecological crisis involve the world above all.68 The “world” is to be distinguished from the “Earth” or the “globe,” with which the world is often confused. The world would seem to be given from the outset, with the physical interdependence of the globe and the ecosystems of the Earth taken as proof. But, unlike the Earth, the world is not self-evident. Our existence on Earth would be very bleak if it were not also part of multiple social and political relationships with others, human and non-human. If the Earth and its ecosystemic equilibriums constitute the conditions for the possibility of collective life, the world in question is of a different nature, as Arendt says:

the physical, worldly in-between along with its interests is overlaid and, as it were, overgrown with an altogether different in-between which consists of deeds and words and owes its origin exclusively to men’s acting and speaking directly to one another.69

This in-between, made up of actions and words, is not reducible to its material scenes, to the intimate circles of communities, or to the economic exchanges of the markets. What is at stake for the collective experience of the world in stock markets and other transactional arenas of global finance or global economies is quite different from what is at stake in demonstrations that aim to protect democracy or take place in the parliamentary spaces of debate. Globalization and worldization are therefore two different, even opposing, processes. The first is the totalizing extension and standardizing repetition of an unequal economy on a global scale, one which destroys cultures, social worlds, and the environment. The second is an opening, through the political action of a living together, of the infinite horizon of encounters and sharing.70 The problem arises when public scenes, where laws and ways of living together are imagined, are usurped by the capitalist interests of the free market, by lobbyists in particular. The ecological crisis is also the manifestation of what Gorz refers to as the “colonization of the life-world”71 and what, in his ecosophy, Félix Guattari called “Integrated World Capitalism,”72 referring to the processes by which the financial interests of certain companies and groups such as Monsanto-Bayer or Total dictate to the rest of the world ways of inhabiting the Earth that are violent and unequal.

Certainly, the importance of the concrete aspects of ecological degradation has led some theoretical approaches to focus solely on the economic and material dimensions of the ecological crisis – nature being included in the material – and led to the continued confusion of the globe with the world. In this vein, Jason Moore’s brilliant analyses of “world-ecology,” inspired by Fernand Braudel and Immanuel Wallerstein, the analyses of political ecology by eco-Marxists, and those of global environmental history paradoxically suffer from the same ills that they denounce: they take the material sphere of physical economic forces impacting the Earth as the main focus for understanding the world.73 Undoubtedly, this global understanding of the ecological crisis in terms of humans’ ecological footprints, “unequal ecological exchange,”74 or “global limits”75 reveals the inequalities between those who consume the equivalent of three or four planets and those who live on almost nothing. And yet, the power of words and political actions are set aside in favor of what can be measured. What remains is what cannot be quantified: suffering, hopes, struggles, victories, refusals, and desires.

This proposition echoes the call of anthropologists and sociologists to focus on other forms of world-making carried out by First Peoples who do not share the modern environmental fracture.76 However, my suggestion that the world be posited as ecology’s horizon is not exactly a call to adopt specific techniques in relation to the environment, ecosystems, spirits, and human beings. Starting from the constitutive plurality of humans and non-humans on Earth, of different cultures, taking the world as the object of ecology brings back to the fore the question of the political composition between these pluralities, and therefore the question of acting together as well. This political approach to the world, in the Greek sense of polis, removes ecology from the single question of the oikos (economic and environmental) because, even if the Earth is indeed strewn with houses, fertile spaces for life and exchanges with it, the Earth is not, however, our home. If these ecumenes are fundamental, then the Earth cannot be adequately represented as one single global oikos. This reduces the Earth solely to the framework of property issues (whose house is it?), cast in the image of the imperial drive to capture and monopolize “territories,” “resources,” and power (who controls it?), like in ancient Greece where a citizen man enslaves the men, women, and children of the household and repels foreigners. This falls back into a violent territorial and root-identity thinking that Édouard Glissant denounced, a way of thinking that still presents the Earth as a colonial and slave-making oikos, and still maintains the colonial ecology model.77

Earth is the world’s womb, its matrix.78 From this perspective, ecology is a confrontation with plurality, with others different than myself, leading to the foundation of a common world. It is from the cosmopolitical foundation of a world between humans, and with non-humans, that the Earth can become not only what we share but what we have “in common without owning it.”79Arendt’s proposed world horizon is enriched in two different ways with which she was not originally concerned. It is creolized and marked by the recognition of the Caribbean experiences of colonialism and slavery, and it is extended by the political recognition of the presence of non-humans, giving rise to a world between humans and with non-humans. If nature and the Earth are not identical to the world, here, the world includes nature, the Earth, non-humans, and humans, all the while recognizing different cosmogonies, qualities, and ways of being in relation to one another.

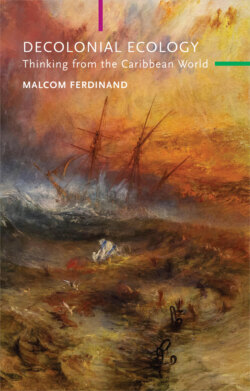

The starting point for thinking ecology from the world cannot be a point that is off-ground, off-world, off-planet, and it cannot be expressed from a being without a body, without color, without flesh, and without a story. Though the history of the Earth is not limited to Western modernity and its colonial shadow – Asia and the Middle East also had their empires and colonialisms – it is here from this shadow that I wish to contribute with this work to thinking about the Earth and the world. My starting point is the Caribbean and its multiple experiences, with a particular emphasis on Martinique, the island where I was born. I speak first in my name, from my body, and the experiences of my native land. I. A Martinican Black man, I lived the first eighteen years of my life in the rural town of Rivière-Pilote and in the small city of Schœlcher, and the next sixteen in Europe, Africa, and Oceania. I will no longer speak from the usual categories of “Man” (with capital M) or “man” (with a lowercase m), as the Caribbean writer Sylvia Wynter invites us to stop doing. This term reflects the over-representation of the White man of the upper classes who wishes to usurp the human and its constituent plurality.80 By claiming to designate both the male of the human species and the entire species as such, this word perpetuates the invisibilization of women, of their places and their actions, as well as the acts of violence that are committed against them. “Man” has never acted upon or inhabited the Earth; it has always been humans, persons, groups, hybrid human/non-human groups that act, struggle, and meet upon the Earth.81 To take the world as the starting point and the horizon of ecology is, in essence, to approach the ecological crisis with the following questions: how can a world be made on Earth between humans and with non-humans? How can a world-ship be built in the face of the tempest? These are the questions that guide this worldly-ecology.