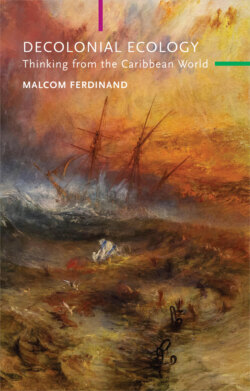

Читать книгу A Decolonial Ecology - Malcom Ferdinand - Страница 22

1 Colonial Inhabitation: An Earth without a World

ОглавлениеConquérant (1776–7)

On May 21st, 1776, the Conquérant, a 300-ton ship, began its journey from Nantes, heading for West Africa. From August to October, while surveying the Gulf of Guinea, the Conquérant inspected and chose the materials-bodies for its building site. Among the 400 pieces packed into the hold and the steerage, only 338 survived the bloody swell of the middle passage, reaching Port-au-Prince on January 9th, 1777. After removing the weeds, the forest, and the Red Amerindians, the Conquérant joined the Negro joists together into the frame of a colonial inhabitation of the Earth.

The current ecological storm is bringing to light the harm and the problems associated with certain ways of inhabiting the Earth that are inherent to modernity. A long-term [longue durée] perspective is required to understand these problems. One must return to modernity’s founding moments and processes, which have contributed to today’s ecological, social, and political situation. This is why it is important to go back as early as 1492, to the founding moment of the European colonization of the Americas. However, it has to be said that this event remains a prisoner to the modern world’s double colonial and environmental fracture. On the one side, anticolonial critique condemns the conquests, the genocide of Amerindian peoples, the violence against Amerindian and Black women, the transatlantic slave trade and the enslavement of millions of Black people.1 On the other side, environmental criticism highlights the extent of ecosystem destruction and the loss of biodiversity that has been caused by the European colonization of the Americas.2 This double fracture erases the continuities that saw humans and non-humans confused as “resources” feeding the same colonial project, the same conception of the Earth and the world. I propose that this double fracture be healed by returning to colonization’s principal action: the act of inhabiting.

The European colonization of the Americas violently implemented a particular way of inhabiting the Earth that I call colonial inhabitation. Although European colonization is plural in terms of its nations, peoples, and kingdoms, its politics, practices, and different periods, colonial inhabitation draws a common thread, which I will describe here with a particular focus on the French experience. The deeds creating French companies, such as the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe, which financed and founded the exploitation of the Caribbean islands, explicitly stated the intention to render these islands inhabited:

We, the undersigned, acknowledge and declare that We have made and do hereby make a faithful association between Us … to render inhabited and populate the islands of Saint-Christophe [present day Saint Kitts and Nevis] and Barbados, and others at the entrance of Peru, from the eleventh to the eighteenth degree of the equinoctial line, which are not possessed by Christian princes, both for the purpose of instructing the inhabitants of said islands in the Catholic, apostolic, and Roman religion, and for the purpose of trading and negotiating in said islands for money and merchandise which may be collected and drawn from the said islands and surrounding areas, and brought to Le Havre to the exclusion of all others ….3

This inhabiting might seem obvious at first glance. The ones who inhabit would be those who are there, those who populate the Earth. It was quite different, however, as evidenced by the vocabulary used. Plots of forest cleared to plant tobacco or sugar cane were designated as “inhabited” land.4 The houses of the enslaving colonists were called – and still are today – habitations or bitations in Creole. The male occupant of such a habitation or dwelling is therefore called a habitant or inhabitant. Colonial inhabitation was therefore based upon a set of actions that determined the boundaries between those who inhabit and those who do not inhabit. Lands exist that are said to be “inhabited” and others that are not. There are houses that are habitations and others that are not. People populated these islands without being designated as “inhabitants.” Conversely, there were inhabitants that rarely resided in their habitations.

By “colonial inhabitation,” I mean something other than a habitat, a style of architecture, or a kind of occupation and culture. If Martin Heidegger has clearly shown that inhabiting (or dwelling) and building are not circumstantial activities of man but constitute, to the contrary, an unsurpassable modality of his being, Heidegger still did not make it possible to understand colonial inhabitation.5 Heideggerian dwelling assumes a totalized Earth and a solitary man, immobile in his dwelling. However, philosophically grasping colonial inhabitation requires an interest in these others and their becomings, in these other lands, in these other humans and these other non-humans. This is what the Martinican poet and philosopher Aimé Césaire proposes in his poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal [Notebook of a Return to the Native Land] which brings to the forefront “those without whom the earth would not be the earth.” Césaire provides a conception of inhabitation that does not “take the other into account,” but which can only be conceived of on the condition of the presence of others. Without others, the Earth is not the Earth, only deserted or desolated ground. Inhabiting the Earth begins through relationships with others. Therefore, colonial inhabitation refers to a singular conception with regard to the existence of certain human beings on Earth – the colonists – of their relationships with other humans – the non-colonists – as well as their ways of relating to nature and to the non-humans of these islands. This colonial inhabitation involves principles, foundations, and forms.