Читать книгу A Decolonial Ecology - Malcom Ferdinand - Страница 16

Noah’s ark or the colonial and environmental double fracture

ОглавлениеThe first proposition is based on the observation of modernity’s colonial and environmental double fracture. This fracture separates the colonial history of the world from its environmental history. This can be seen in the divide between environmental and ecological movements, on the one hand, and postcolonial and antiracist movements, on the other, where both express themselves in the streets and in the universities without speaking to each other. This fracture is also revealed on a daily basis by the striking absence of Blacks and other people of color in the arenas of environmental discourse production, as well as in the theoretical tools used to conceptualize the ecological crisis. With the terms “Black people,” “Red people,” “Arabs,” or “Whites,” far from the a priori essentialization of nineteenth-century scientific anthropology, I am referring to the construction of the racist hierarchy of the West that resulted in many peoples on Earth having the condition of being associated with a race, culminating in the invention of Whites above non-Whites.4 Because of this asymmetry, I refer to those others, non-Whites, by the term “racialized,” for it is their humanity that has been and is being contested by these racial ontologies, and it is they who de facto suffer a discriminatory essentialization.5 Even though this hierarchy is a socio-political construction that no longer has any scientific value, it should not in turn lead to the denial of the ensuing social and experiential realities (for example, by refusing to name them) or the denial of their violence, including when those realities and violence take place within environmental discourses, practices, and policies.6

In the United States, a 2014 study showed that minorities remain under-represented in governmental and non-governmental environmental organizations, with the highest positions held predominately by White, educated, middle-class men.7 A similar situation exists in France. Racialized people who have come as part of colonial and postcolonial migration and who collect the cities’ garbage, clean public squares and institutions, drive buses, trams, and subway trains, the ones who serve hot meals in university dining halls, deliver mail, care for the sick in hospitals, those whose welcoming smiles at the entrance of establishments are a guarantee of security, are the same ones who are usually excluded from the university, governmental, and non-governmental arenas that focus on the state of the environment. As a result, environmental specialists regularly speak at conferences as if all these people, their stories, their suffering, and their struggles remain inconsequential to the way we think about the Earth. This leads to the absurdity that the planet’s preservation is thought about and implemented in the absence of those “without whom,” as Aimé Césaire writes, “the earth would not be the earth.”8 Either this fracture is completely hidden behind the fallacious argument that non-White peoples do not care about the environment, or it is restricted to a subject that is deemed secondary to the “real” purpose of ecology. My proposition here is that this double fracture be positioned as a central problem of the ecological crisis, thereby radically transforming its conceptual and political implications.

On the one hand, the environmental fracture follows from modernity’s “great divide,” those dualistic oppositions that separate nature and culture, environment and society, establishing a vertical scale of values that places “Man” above nature.9 This fracture is revealed through the technical, scientific, and economic modernizations of the mastery of nature, the effects of which can be measured by the extent of the Earth’s pollution, the loss of biodiversity, global warming, and the associated persistence of gender inequality, social misery, and the “disposable lives” that are thereby created.10 The concept of the “Anthropocene,” popularized by Paul Crutzen, winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, attests to the consequences of this duality.11 It refers to the new geological era that comes after the Holocene, in which human activities have become a major force impacting the Earth’s ecosystems in a lasting way. This fracture also conceals a horizontal homogenization and hides internal hierarchizations on both sides. On the one side, the terms “planet,” “nature,” or “environment” conceal the diversity of ecosystems, geographic locations, and the non-humans that constitute them. Images of lush forests, snow-capped mountains, and nature reserves mask those of urban natures, slums, and plantations. Also masked are the internal conflicts between nature conservation movements and animal welfare movements, the animal fracture, as well as the latter’s own hierarchies in which “noble” wild animals (polar bears, whales, elephants, or pandas) and pets (dogs and cats) are placed above animals that are farmed (cows, pigs, sheep, or tuna).12 On the other side, the terms “Man” or anthropos mask the plurality of human beings, featuring men and women, rich and poor, Whites and non-Whites, Christians and non-Christians, sick and healthy.

The environmental fracture

I call “environmentalism” the set of movements and currents of thought that attempt to reverse the vertical valuation of the environmental fracture but without touching the horizontal scale of values, meaning without questioning social injustices, gender discrimination, political domination, or the hierarchy of living environments and without concern for the treatment of animals on Earth. Environmentalism therefore proceeds from an apolitical genealogy of ecology comprised of its figures, like the solitary walker, and its pantheon of thinkers, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Pierre Poivre, John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, or Arne Næss.13 They are mainly White, free, solitary, upper-class men in slave-making and post-slavery societies gazing out over what is then referred to as “nature.” Despite disagreements over its definition, environmentalism remains preoccupied with “nature,” cherishing the sweet illusion that its socio-political conditions of access and its sciences might remain outside the colonial fracture.14

Since the 1960s, some ecological movements have been concerned with addressing vertical and horizontal scales of value. Ecofeminism, social ecology, and political ecology have argued for a preservation of the environment intrinsically linked to demands for gender equality, social justice, and political emancipation. Despite their rich contributions, these green interventions make little room for racial and colonial issues. The colonial and slave-making constitution of modernity is veiled by pretentious claims to the universality of socio-economic, feminist, or juridico-political theories. In the green turn of the 1970s, arts and humanities disciplines confronted the environmental fracture while at the same time sliding the colonial divide under the rug. The absence of people of color who are experts on these issues is striking. From universities to governmental and non-governmental arenas, movements critical of the environmental fracture have marked the boundaries of a predominantly White and masculine space within postcolonial, multiethnic, and multicultural countries where the maps of the Earth and the dividing lines of the world are imagined and redrawn.

On the other hand, there is a colonial fracture sustained by the racist ideologies of the West, its religious, cultural, and ethnic Eurocentrism, and its imperial desire for enrichment, the effects of which can be seen in the enslavement of the Earth’s First Peoples, the violence inflicted on non-European women, the wars of colonial conquest, the bloody uprooting of the slave trade, the suffering of colonial slavery, the many genocides and crimes against humanity. The colonial fracture separates humans and the geographical spaces of the Earth between European colonizers and non-European colonized peoples, between Whites and non-Whites, between the masters and the enslaved, between the metropole and the colonies, between the Global North and the Global South. Going back at least to the time of the Spanish Reconquista, when Muslims were expelled from the Iberian peninsula, and the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas in 1492, this fracture places the colonist, his history and his desires at the top of the hierarchy of values and subordinates the lives and lands of the colonized or formerly colonized under him.15 In the same way, this fracture renders the colonists as homogeneous, reduces them to the experience of a White man, while at the same time reducing the experience of the colonized to that of a racialized man. Throughout the complex history of colonialism, this line has been contested by both sides and has taken different forms.16 Nevertheless, it persists today, reinforced by free markets and capitalism.

The colonial fracture

From the first acts of resistance by Amerindians and the enslaved in the fifteenth century to contemporary antiracist movements and anticolonial struggles in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, this colonial fracture is being called into question, exposing the vertical valorization of the colonized by the colonist. Anticolonialism, antislavery, and antiracism together represent the actions and currents of thought deconstructing this vertical scale of values. History has shown, however, that these movements have not always challenged the horizontal scale of values that in places maintains the relationships of domination between men and women, rich and poor, urban dwellers and peasants, Christians and non-Christians, Arabs and Blacks, among the colonized as well as among the colonists. In response, movements such as Black feminism and decolonial theory shatter both vertical and horizontal value scales, linking decolonization to the emancipation of women, recognition of different sexual orientations and different religious faiths, as well as to social justice. However, the ecological issues of the world remain relegated to the background.

The double fracture of modernity refers to the thick wall between the two environmental and colonial fractures, to the real difficulty that exists in thinking them together and that in response carries out a double critique. However, this difficulty is not experienced in the same way on either side, and these two fields do not bear equal responsibility for it. On the environmentalist side, this difficulty stems from an effort to hide colonization and slavery within the genealogy of ecological thinking, producing a colonial ecology, even a Noah’s Ark ecology. With the concept of the Anthropocene, Crutzen and others promote a narrative about the Earth that erases colonial history, while the country of which Crutzen is a citizen, the kingdom of the Netherlands, is a former colonial and slaveholding empire that stretched from Suriname to Indonesia via South Africa, and now consists of six overseas territories in the Caribbean.17

In metropolitan France [France hexagonale], or the Hexagone, environmentalist movements have not made anticolonial and antiracist struggles central elements of the ecological crisis.18 These struggles remain anecdotal or are even ignored within the extensive critiques of technology (including of nuclear power) carried out by Bernard Charbonneau, Jacques Ellul, André Gorz, Ivan Illich, Edgar Morin, and Günther Anders. The damage caused by nuclear tests carried out on colonized lands, such as the 210 French tests in Algeria and those in Polynesia from 1960 to 1996, is downplayed, but so is the damage caused by the plundering of mines in Africa by Great Britain and France and by the exploitation of the subsoil of Aboriginal lands in Australia, the First Nations in Canada, the Navajos in the United States, and of the Black workers forced to extract uranium in apartheid South Africa.19 In addition to transforming the Hexagone, nuclear energy has relied on France’s colonial empire, using mines in Gabon, Niger, and Madagascar – which have long been in use throughout Françafrique – while exposing miners to uranium and radon gas.20 To disavow this colonial fact is to cover up the opposition to nuclear power that has been voiced by anticolonial movements, such as the demand for disarmament made by the Bandung Conference of 1955, or Kwame Nkrumah, Bayard Rustin, and Bill Sutherland’s pan-Africanist rejection of “nuclear imperialism” and French nuclear tests in Algeria, or Frantz Fanon’s denunciation of a nuclear arms race that maintains the Third World’s domination, or the contemporary demands for justice by Polynesians.21 By omitting the colonial conditions for the production of technology, environmentalist movements have missed possible alliances with anticolonial critiques of technology.

Certainly, there were some bridges that were built in light of René Dumont’s commitments to the peasants of the Third World, Robert Jaulin and Serge Moscovici’s denunciations of the ethnocides of the Amerindians and their collaboration with the group “Survivre et vivre” [Survive and live], which led to a critique of the scientific imperialism that serves the West and the rare support of overseas citizens.22 Today, Serge Latouche is one of the few people in France who has placed the decolonial demand at the heart of ecological issues.23 Despite these rare examples, colonized others have not had important speaking roles within the French environmentalist movement, cast away with “their” history to a distant beyond that is reinforced by the illusion of a North/South dichotomy. The result is a sympathy-without-connection [sympathie-sans-lien] where the concerns of others that are “over there” are recognized without acknowledging the material, economic, and political connections to the “here.” It is taken as self-evident that the history of environmental pollution and the environmentalist movements “in France” does not include its former colonies and overseas territories,24 that the history of ecological thinking continues to be conceived of without any Black thinkers,25 that the word “antiracism” is not part of the ecological vocabulary,26 and, above all, that these absences do not pose any problems. With expressions such as “climate refugees” and “environmental migrants,” green activists appear to be discovering the migratory phenomenon in a panic, while they make a tabula rasa out of France’s historical colonial and postcolonial migrations from the Antilles, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. So, it remains a cognitive and political embarrassment to recognize that French overseas territories are home to 80 percent of France’s national biodiversity and 97 percent of its maritime exclusive economic zone, without addressing the fact that the inhabitants there are kept in poverty and on the margins of France’s political and imaginary representations.27 Aside from such sympathies-without-connection, the encounter between environmentalist movements and thought of the Hexagone with the colonial history of France and its “other citizens” has not yet taken place.28

As Kathryn Yusoff notes, this invisibilization results in a “White Anthropocene,” the geology of which erases the histories of non-Whites, and a Western imaginary of the “ecological crisis” that erases colonial experiences.29 A colonial arrogance persists on the part of present-day “collapsologists” when they talks about a new collapse while concealing the connections that exist to modern colonization, slavery, and racism, the genocides of indigenous peoples, and the destruction of their environments.30 In his book Collapse, Jared Diamond describes the postcolonial societies of Haiti and Rwanda through a condescending exoticism that places them in a distant off-world [hors-monde] and that does not include any scientists or thinkers from these countries.31 These people, who are “more African in appearance” according to Diamond, are reduced to the role of victims who lack knowledge.32 The colonial constitution of the world and the resulting inequalities are passed over in silence.33 The Anthropocene’s claim to universality seems to be sufficient to dismiss critics of the West’s discriminatory universalism.34 Could it really be that a global enterprise, which from the fifteenth to the twentieth century was predicated upon the exploitation of humans and non-humans, including the decimation of millions of indigenous people in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, the forced transportation of millions of Africans, and centuries-long slavery, has no material or philosophical relationship with ecological thinking today? Are the ecological crisis and the Anthropocene new expressions of the “White man’s burden” to save “Humanity” from itself?35 Fracture.

On the other side, the racialized and the subalterns who are met with repeated refusals of the world feel this double fracture every day in their flesh and in their stories. W. E. B. Du Bois’s “veil” expanded upon by Paul Gilroy’s “double consciousness of modernity,” Enrique Dussel’s “underside of modernity,” and the “White masks” on Fanon’s Black skin or Glen Coulthard’s Red skin are only different ways of describing this violence.36 From 1492 to today, we must bear in mind the incommensurable resistance and struggles on the part of colonized and enslaved men and women in demanding humane treatment, to engage in a profession, to preserve their families, to participate in public life, to practice their arts, their languages, to pray to their gods, and to sit at the same world table. Yet those who carry the weight of the world see their struggles, like the Haitian Revolution, silenced.37 In these pursuits of dignity – those that focus primarily on issues of identity, equality, sovereignty, and justice – environmental issues are perceived as an extension of colonial domination that fortifies the holds, exacerbates the suffering of racialized people, the poor, and women, and sustains colonial silence.

A dangerous alternative emerges. Either this legitimate mistrust of environmentalism leads to the neglect of the dangers of environmental devastations of the Earth. Ecological struggles would then be a matter of “white utopia,” or at the very least unimportant when faced with the immense task of reclaiming dignity.38 Or, paradoxically, in their laudable calls for ecological sensitivity, postcolonial thinkers such as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Souleymane Bachir Diagne will have discarded their critical theoretical tools and adopted the same environmentalist terms, scales, and historicities, such as, for example, “global subject,” “whole Earth,” and “humanity in general.”39 The durability of the psychological, socio-political, and ecosystemic violence and toxicity of the “ruins of empires” is concealed.40 Likewise, one underestimates the colonial ecology of racial ontologies that always links the racialized and the colonized to those psychic, physical, and socio-political spaces that are the world’s holds. This is true whether it is a matter of the spaces of legal and political non-representation (the enslaved), the spaces of non-being (the Negro), the spaces of the absence of logos, history, or culture (the savage), the spaces of the non-human (the animal), the spaces of the inhuman (the monster, the beast), the spaces of the non-living (camps and necropolises), or, if it is a matter of geographical locations (Africa, the Americas, Asia, Oceania), of habitat zones (ghettos, suburbs) or of ecosystems subject to capitalist production (slave ships, tropical plantations, factories, mines, prisons). In turn, the importance of ecological and non-human concerns within (post)colonial struggles for equality and dignity remain understated. Fracture.

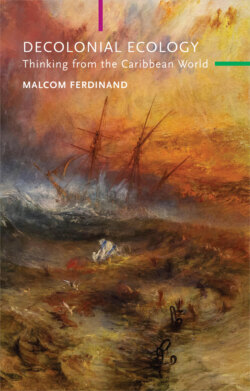

Here is the double fracture. One either questions the environmental fracture on the condition that the silence of modernity’s colonial fracture, its misogynistic slavery, and its racisms are maintained, or one deconstructs the colonial fracture on the condition that its ecological issues are abandoned. Yet, by leaving aside the colonial question, ecologists and green activists overlook the fact that both historical colonization and contemporary structural racism are at the center of destructive ways of inhabiting the Earth. Leaving aside the environmental and animal questions, antiracist and postcolonial movements miss the forms of violence that exacerbate the domination of the enslaved, the colonized, and racialized women. As a result of this double fracture, Noah’s Ark is established as an appropriate political metaphor for the Earth and the world in the face of the ecological tempest, locking the cries for a common world at the bottom of modernity’s hold.