Читать книгу During My Time - Margaret B. Blackman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

Squeezed between hardcover is the text of a life, its beginnings, its turning points, its closure at the time of the telling. It represents in some ways a final statement, an authoritative text on a life lived and recalled, but in reality a life story is never finished with publication. The book presents but one version of the life as told, and the story and the text are further subject to alterations over time as the narrator ages, rethinks, revises, and retells, and as the editor reconsiders the representation of life history material. Such re-examination, in both its affirmation and revision of the original, enriches our understanding of the life history process. At a time when reflexivity, the questioning of textual authority, and close examination of narrative structures direct many anthropological endeavors, new readings of old texts is a critical enterprise. But few anthropological life histories have undergone re-examination to the extent of being issued in second editions.1

Within this context, I was motivated to re-examine During My Time. In the summer of 1990, ten years following completion of the manuscript, I sat first with Florence Davidson to record her reflections on her published life story and then with several members of her family to record theirs. My narrative of that research and of the magnificent 95th birthday party fête held for Florence the preceding year comprises the epilogue, “One More Time.”

An issue central to the writing of that epilogue is the nature of Native American biography and life history today and our unique role as authors/editors of those works. Questions of audience, the politics of cultural representation, and the changing narrative of Native American history are all raised in the re-examination of Florence’s story and my attempt to update it.

The collaborative nature of life histories from inception to print, especially those from Native North America, is emblematic of the times in which we write and of the larger relationships between the scholarly community and the communities of people we research. Much has been written recently in anthropology of the dispersal of ethnographic authority, the democratization of anthropological research, the blurring of lines between the researcher and the researched.2 Canadian native people have asserted their current status as “First Nations People” at the same time that the anthropological community has elevated its native “informants” to “native teachers,” “research consultants,” and “native experts.” Edward Bruner (1986) and, following him, James Clifton (1989) document the changing anthropological and historical view of Native American cultures, from a narrative of forced acculturation and social disorganization leading to assimilation, to one of self-determination, resistance, and nationhood. The change in the narrative of Native American history follows sweeping political and economic changes in the years following World War II, during which time Native Americans gained greater control over their own destinies. Under today’s conditions, anthropologists have difficulty doing research without formal tribal approval and “deliver their manuscripts to tribal governments for commentary, criticism, and correction before publication” (Clifton 1989:4). Obviously such circumstances make portrayal of conflict and other sensitive issues both more difficult and more challenging in life histories. At the same time they also make the life history a welcome genre in native communities. The anthropologist is led to exemplary lives, not just because the published life stories are to be offered to the larger world, but because the narratives return home to become community history as well as models for the fashioning of lives and life stories. Florence is a good model. She did what was expected of a woman of her time and did it well: she is community-spirited and has tirelessly served her community through her various leadership roles within the Anglican church. She was and continues to be a devout Christian. She raised her children to be prominent and active citizens; she shows, in the Haida way, “respect for herself.” Florence and her family fulfill their social-ceremonial obligations. And they manage their money well, with the result that very few of their large extended family are on welfare. Florence’s is the exemplary life, its value enhanced because of her age and the period of history to which her experience reaches.

In a community such as Masset, a life history is never simply the product of two individuals’ collaboration. Florence’s account was subject to a number of cultural constraints. Issues of cultural representation and presentation of self are crucial in Northwest Coast societies, with no exception in Masset. One’s prominence and social standing should be apparent, but not through public self-proclamation. It is acceptable to describe the hard work you’ve always done, but you shouldn’t “brag” about being from a chief’s family, extol your own or your children’s good behavior or accomplishments, or publicly berate someone else, even though in certain circles you may do all these things. Gossip, accusations, commentary on other people’s social misbehavior and stinginess in comparison with one’s own exemplariness fill the spaces about the kitchen tables in Masset, but are not fare for public speechmaking, nor for life histories, particularly if the author wishes to maintain good ties in a village where inevitably one’s book is “read.”

Florence’s own editorial hand in her life history was apparent from the very beginning. “I don’t tell everything—what’s no good” she cautioned, as I noted in the first edition. On more than one occasion, she would instruct me to “shut that thing off” while she relayed something important that was not to be included in the book. Interviews with her and her family in the summer of 1990 included similar instructions and/or material proffered on tape but “off the record.” Some reviewers of the first edition of the life history complained about these omissions: “The untold stories lie beneath the facts. The main element missing in this life story is conflict” (Jackson 1983:56). If we are interested in how people construct their identities and how they tell their stories, we must read the omissions, with the understanding that they, in their own way, also tell the story. On a more operational level, the very kinds of things that lead to lawsuits when biographers transgress agreements with their subjects make the anthropologist at the least an unwelcome guest in the native community and increasingly lead to formal resolutions banning anthropologists, as happened with one ethnographer in Masset in 1983.3

Every life history interviewee obviously edits the telling of his or her story, and consequently every life history is a partial story. But some life stories contain more conflict or seem more candid, less guarded, than others. In some cases the explanations may lie in culturally specific traditions of self-revelation and public discourse, but the reasons may be more blatantly political. In Marjorie Shostak’s (1981) popular life history of a !Kung San woman, Nisa, the interviewee speaks freely about her sexuality, her husbands, her extramarital affairs. Had members of the interviewee’s own community had access to the book’s contents, her story might have been less freely told, the author concludes.4 But Nisa’s people are not literate and do not speak English, and she knows little of the world that her story has reached. By contrast, Florence’s book is not only marketed in her own community but nonlocal purchasers come to meet her, locals read the book, and she and members of her family have given the book as presents. Her narrative conveys her public self; “the world’s Nani,” as she sometimes jokingly refers to herself, offers the world her story.

The individuality of the life history endeavor can be misleading. Florence worked with me always on an individual basis and, very much her own person, decided what to include in her story. Nonetheless, that she is also the senior member of a large, prominent, and very protective family was not lost on the final document. Family members offered retrospective views on the book in 1990, and even though they were not interviewed when I did my initial research between 1977–79, a copy of the manuscript was circulated among Florence’s children in Masset. Both directly and obliquely their comments reached me. They expressed more concern about my parts of the manuscript than about their mother’s narrative, though one comment was made about my grammatical editing (or lack thereof) of one of Florence’s statements. There was some distress at my reliance on “books” rather than people as authoritative sources on Haida ethnography, as well as concern about my choice of words in certain passages. In particular, they focused on my use of the term “ordinary” in describing their mother’s life. “Ordinary” held connotations of “common,” and Florence, of course, was anything but “common” in the Haida social hierarchy. Clarification was easy enough to make, as I did by noting that the reference was to Florence’s self-perceptions of the uneventfulness of her life. More important, this was a lesson both in the care with which appropriate words are selected in the Haida world and in the power of words to affect a person’s social standing.5 Family were equally concerned lest Florence be identified with comments about the Haida ranking system; especially bothersome was quoted material on this ranking system (p. 24) attributed to Florence. Social position is everything in Masset, but when it comes to mention of the aboriginal social system of chiefs, commoners, and slaves, people are quick to publicly assert, “but we’re all equal now.” Noting that so-and-so’s great-grandfather was a slave or perhaps even mentioning the qualities that identified those who did and did not belong to chiefly families is kitchen-table talk, but not acceptable public discourse, permissible for the ethnographer’s edification, but not for attribution in print to the human source. To talk about such things publicly is not “high class.” The information was left in; the reference to its source was deleted.

Despite their pre-publication concerns, the family appear generally happy with the book. It has brought Florence both some income and some positive attention from the outside world. She is, after all, now “the world’s Nani.” The book is testimony to who she is, not only through her own words but also through those of an outside speaker, the anthropologist. It is, so far, the only life history of a living Haida.6 Its uniqueness is not lost on Florence. One morning in 1983 as we lingered over tea at her kitchen table, she told me of another Haida woman and the ethnographer who attempted to do her life history; “They tried to copy us,” she sniffed. As the only one, Florence’s life history is a model of sorts. An elderly Haida woman in the summer of 1989 approached an ethnographer working for the Masset Band and asked if she would be willing to write her life history, “just like Florence Davidson’s.” The unspoken caveat was, “only better.” Of course, During My Time is also not without its detractors in the local Haida community; Florence’s long-time rivals predictably pronounced it a pack of lies the minute it was published.

Though it is not known exactly how the book is “read” in Masset (save that my parts, as one family member confessed, could be deleted without harming the integrity of Florence’s life story), that it is read and even marketed locally speaks volumes on the anthropologist/Native American community relationship.

I talked with family members about the book. Not all had read it from cover to cover despite the pre-publication scrutiny given the manuscript. There was interest in what I had to say in respect to the issue of cultural representation, but that aside, it became apparent that life histories intended for local use do not need introductions, analyses, summaries, and afterwords. Some outsiders concur that the narrative is best left to stand on its own. Complained one reviewer of the book, “During My Time threatens to overwhelm Nani’s delicate, rather shy reminiscences with an overly academic context…. Blackman is formal and scrupulous in providing ethnographic background, bracketing Nani with forewords and afterwords, footnotes and bibliographies” (Jackson 1983:56).

But how was Florence’s narrative itself perceived by her family? Everyone agreed that there were no surprises nor any glaring omissions in Nani’s story, even though in our interviews each contributed new dimensions to Florence’s story. One comment, offered by daughter Virginia Hunter, was particularly revealing regarding ownership of the story and the role of the collaborator in its creation. Racking her brain to recall the book she had read so long ago, she suddenly remembered a portion of it that struck her as strange. “I just wondered,” she questioned me, “why Mom kept talking about having her period. A woman has her period. They’re so superstitious about things like that. I couldn’t understand why she would talk about something like that in her book, because they weren’t even allowed to talk about what they went through.” I remembered well the interview Florence and I had about her seclusion at menarche and our subsequent discussion of menstrual customs, a subject she would not consider broaching until the male linguist residing with her at the time had vacated the house for the day. That important life-cycle material was included in the manuscript at my urging (see chapter 7), yet obviously it was seen neither as normal Haida discourse nor as Florence’s discourse on her life.

In every life history, the final shape of the narrative, both consciously and not, is determined by the editor/author and the narrator. Asymmetries in this collaboration, however, give the advantage to the editor. The narrator, less familiar with the world of books and publishing, may defer to the editor, as Florence did sometimes in our interviews when she instructed me: “Just ask me questions.” Or as she told me during our most recent interview: “Just write it down the way you think it’s best.” The life story is also manifestly a product of the times in which it is told and written. As I confessed in the first edition, my inquiry was driven towards more traditional Haida customs that continued to be practiced by Florence and others of her time; thus my focus on her seclusion at menarche and her arranged marriage and my interest in feasting and potlatching. Given the notable Haida ceremonial efflorescence in recent years which has paralleled the political evolution of the Haida Nation, if Florence’s story were told today, it might well focus more on recent ceremonial events than it did between 1977–79.7 Similarly, my own inquiry would attend more to domains short shrifted in the original, such as the role of the church and Christianity in Florence’s life.

In the intervening years since During My Time was published, public interest in the life history has continued to intensify. In a survey taken in 1985, the Library of Congress reported that more people had read a biography in the previous six months than any other form of literature, and since the 1960s the number of biographical titles has virtually doubled each year (Oates 1986:ix). There is a universal appeal to the life history, for it is testimony that each of us has a life worth relating, a story to tell. It is an inclusive, as opposed to an exclusive, form. The life stories of the Florence Davidsons take their places among the ghost-authored autobiographies of the Nancy Reagans and the Donald Trumps. The life story is also seen—for a price—as anyone’s route to immortality or at least to a place, however modest, in history. The February 1989 issue of the popular high-tech catalogue The Sharper Image made the following limited offer to its more up-scale customers: “Hold the story of your life in your hands in a custom-written, leather-bound biography.” Touted as a personalized treasure that would only appreciate in value with each reading, it was available for a mere $27,000. Appealing to a much wider audience, the U. S. Postal Service in 1988 offered free genealogical charts as part of a program encouraging children, through oral history interviews, to learn from their grandparents their family history. Works such as William Zimmerman’s How to Tape Instant Oral Biographies and the Foxfire series also make the point that the life history is not confined to the rarefied realm of the academy but is a form of endeavor open to all.

The life history is enjoying a renewed popularity in Anthropology as well. The sharing of ethnographic authority, the growing recognition of multivocality, heterogeneity, and cultural diversity within cultures once oversimplified as homogeneous have bestowed increased credibility and value on personal experience and individual narratives. No longer justified primarily in terms of what they reveal about culture or how they amplify other ethnographic data, life histories are increasingly being read and understood as texts that reveal the multiple ways in which people conceptualize, integrate, and present their lives to others.

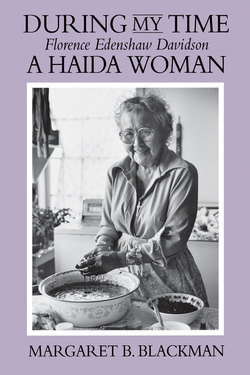

More difficult to calculate is the personal value of the life history. For both the subject and the interviewer, the life history endeavor holds a gift. For the narrator, it offers an unparalleled opportunity for life review to an attentive audience; for the interviewer, it offers the receipt of a well-told story with all its insights, reflections, and shared experience. As one anthropologist confessed, the life history endeavor is “a constant meditation on life.”8 For Florence and me, the process is ongoing; I return each year not only to renew our close personal relationship and to have my daughter know the woman she calls her great Nani, but to continue to touch and learn from the life Florence has shared with me.

MARGARET B. BLACKMAN

January 1992

1. See, for example, Keesing (1983), Underhill (1978). Marjorie Shostak is in the process of writing a second edition of Nisa. Other accounts ask new questions of old texts: e.g., Krupat (1985), Brumble (1988), Bataille and Sands (1984).

2. See, for example, Marcus and Fischer (1986), Clifford and Marcus (1986), and Clifford (1988).

3. See Ames (1986:43–44).

4. Marjorie Shostak, personal communication.

5. Proper and skilled speechmaking is a valued Haida attribute, so it is not surprising that such concerns would extend to the biographer of a Haida. See Boelscher (1988) for a discussion of contemporary Haida speechmaking.

6. Biographical accounts of the artistic careers and works of Haida artists Robert Davidson and Bill Reid have appeared (Stewart 1979; Shadbolt 1986), and there are biographical accounts of past Haida as well (Robinson 1978; Morley 1967). However, all these differ considerably from the life history.

7. Just within Florence’s family since 1987, in addition to her birthday feast, there have been three memorial potlatches, two totem-pole raisings, and the taking up of a chieftainship; planned for the fall of 1991 is another headstone-moving and a totem-pole raising.

8. Gelya Frank, personal communication.