Читать книгу During My Time - Margaret B. Blackman - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The Life-History Project

… the life history is still the most cognitively rich and humanly understandable way of getting at an inner view of culture. [No other type of study] can equal the life history in demonstrating what the native himself considers to be important in his own experience and how he thinks and feels about that experience. [Phillips 1973:201]

THE LIFE HISTORY IN ANTHROPOLOGY

The writing of native life histories has long been regarded by anthropologists as a legitimate as well as popular approach to understanding and describing other cultures.1 In 1922, for example, anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons wrote in the preface to her biography of a Zuni woman: “In our own complex culture biography may be a clarifying form of description. Might it not avail at Zuni?” (Parsons 1922:158). Alfred Kroeber, who wrote the introduction to American Indian Life, in which Parsons’ article appears, believed that the unique contribution of this collection of biographical sketches was their insight into the social psychology of the American Indian. Unfortunately, most of the contributors to this volume found it necessary to fictionalize the life histories, inventing characters for the ethnographic data on the individual life cycle.

While it is fortunate that fictionalized life histories have been the exception in anthropological research, their very existence points to the significance of the medium for presenting the cultural record. The utility and success of the life-history approach in anthropology can be attributed to a number of factors. In the first place, the basic fabric of ethnology is woven from the scraps of individuals’ lives, from the experiences and knowledge of individual informants. Many ethnographic accounts of subsistence activities, marriage, and ritual observances, for example, are derived directly from the personal experiences of members of a culture, and as anthropologists work closely with selected informants, the presentation of ethnographic data from the longitudinal perspective of the individual life is not surprising. “Culture” as lived by the individual represents the ultimate inside view, and the life history thus serves as a useful complement to the standard ethnography.

The life history also complements the ethnographic account by adding to the descriptive an affective or experiential dimension. We know, for example, from early ethnographic accounts of Haida culture the form and function of the girl’s puberty ritual and the structure of Haida marriage, and from more recent ethnohistoric studies we know the changes wrought in Haida culture following contact. But these sources do not really address the question of meaning: What was the puberty seclusion really like? What did it mean to the individual to have his or her marriage arranged at an early age? How did individuals respond to various cultural changes? The life history is uniquely suited to addressing this kind of question.

The life history is also an appropriate medium for the study of acculturation. In many cultures the lives of natives span periods of critical and rapid culture change; the life history affords a personalized, longitudinal view of these changes.

Kluckhohn (1945), in a now classic article on the use of personal documents in anthropology, adds that life histories can be avenues to understanding status and role, individual variation within cultural patterns of behavior, personality structure, deviance, and idiosyncratic variation.

Native Americans have been by far the most popular subject material for life histories. Interest in the lives of American Indians began in the nineteenth century as famous and notorious Indian leaders commanded the attention of the public and sparked the writing of romantic and sentimental biographies. Langness (1965), for example, lists thirty-six American Indian life histories published between 1825 and 1900. A more recent and comprehensive accounting of Native American life histories (Brumble 1981), which brings the list up to the 1980s, contains over five hundred entries. Were one to include the numerous non-first-person accounts of Native American lives, which Brumble does not, this total would be considerably larger. The earliest anthropological life histories were also of American Indians (Kroeber 1908; Radin 1913). The recently published biographical sketches in American Indian Intellectuals (Liberty 1978) point to a still-current interest in the “great men”2 of native society, though simultaneously there has been a growing interest in recording the lives of ordinary Native Americans.

Inspired in part by Franz Boas’ early interest in the individual and his field research on the Northwest Coast, a number of life histories of Northwest Coast natives have been published over the years.3 Edward Sapir included a fictionalized life history of a Nootka trader in American Indian Life (Parsons 1922); Diamond Jenness (1955) relied upon the personal reminiscences of “Old Pierre” to compile his treatise on Katzie supernatural beliefs; and Marius Barbeau’s discussion of Haida argillite carvings (1957) included data on the artistic careers of the major Haida slate carvers. Further recognition of the importance of genealogical and life-history data to the study of native Indian art in British Columbia led the Vancouver Centennial Museum in 1977 to initiate a comprehensive collection of biographical data on British Columbia’s Indian artists.

Two Northwest Coast life-history documents span successive generations of recent Southern Kwakiutl culture history and are particularly valuable for their documentation of continuity and change in that culture. In 1940 Kwakiutl Chief Charlie Nowell dictated his life story to Clellan Ford (1941), and in the 1960s James Sewid related his personal history, with the editorial assistance of anthropologist James Spradley (1969). Aside from Barbeau’s brief biographical sketches in Haida Carvers in Argillite (1957) and the account of Chief Gəniyá (“Cunneah”) in Robinson’s Sea Otter Chiefs (1978), the only Haida life history is that of Peter Kelly of Skidegate (Morley 1967). To date, no life histories of native Northwest Coast women have been published, though as early as 1930 several short life histories of Kwakiutl women were collected by Julia Averkieva, a student of Boas (Rohner 1966:198).

In fact, for native North America as a whole there are more than three times the number of male life histories as female life histories. At least in the case of the life histories authored or collected by anthropologists, this imbalance is in large part due to the fact that male ethnographers, who until recently have greatly outnumbered female ethnographers, understandably came to know and work more closely with the male members of the cultures they studied. Then, too, as Rosaldo (1974) has noted, men live much of their lives in the public arena, as policy makers, warriors, intellectuals, and philosophers in native societies. Given such roles it is not surprising that anthropologists should have found the lives of men more visible, interesting, absorbing, and significant than the lives of women. This viewpoint has often affected even those who do write about native women’s lives. Ruth Underhill, for example, justifies Papago Maria Chona’s narrative by demonstrating her affiliation with important men: “As a woman she could take no active part in the ceremonial life. But her father was a governor and a warrior; her brother and husband were shamans; her second husband was a song leader and composer” (Underhill 1936:4). She does add, however, that a Papago woman’s life is interesting in and of itself “because in this culture, there persists strongly the fear of woman’s impurity with all its consequent social adjustments.”

I suspect that anthropologists are more influenced by their own cultural background than they would like to acknowledge. Perhaps the relative neglect of women’s lives in other cultures stems also from the fact that autobiography in the Western tradition has been primarily a male form. As Pomerleau notes:

The traditional view of women is antithetical to the crucial motive of autobiography—a desire to synthesize, to see one’s life as an organic whole, to look back for a pattern. Women’s lives are fragmented…. the process is not one of growth, of evolution; rather … earlier and more decisively than for a man, the curve of a woman’s life is seen by herself and society to be one of deterioration and degeneration. Men may mature, but women age. [1980:37]

In the same volume Jelinek summarizes, “Insignificance, indeed, expresses the predominant attitude of most [literary] critics towards women’s lives” (Jelinek 1980:4).

Only recently have anthropologists taken the view that, even in the absence of criteria such as a belief in woman’s impurity or relationships to powerful men, women’s lives are inherently worthy of consideration. If we are to understand women and their roles in cross-cultural perspective, it is axiomatic that we know the breadth and depth of their life experiences, the ordinary as well as the extraordinary. Margaret Mead has provided us with the latter type of document in her autobiography Blackberry Winter (1972), and in the wake of the women’s movement a number of anthropological monographs that focus on the lives of ordinary women have been published (e.g., Strathern 1972; Jones and Jones 1976; Weiner 1976; Dougherty 1978; Kelley 1978). Accounts of native women’s lives written for a more general audience have also appeared in recent years. In the native North American literature are an overview of the female life cycle in many different tribes (Neithammer 1977), a biography of a well-known Ojibwa woman (Vanderburgh 1977), and autobiographies written by a part-Cree woman (Willis 1973) and a métis woman (Campbell 1973).

Florence Davidson’s life history is the account of one who faithfully fulfilled the expected role of women in her society. For most of her life she has remained outside the public domain; above all else she has participated in her culture as mother and wife, and today she would undoubtedly sum up her identity in the word “Nani.” Despite the social position she has enjoyed as the daughter of high-ranking parents and the esteem that she has earned, Florence Davidson views her life as “ordinary,” in the sense of being uneventful. Once during our taping she sighed and then laughed, “If only I lied, it could be so interesting!” Aside from recounting the life experiences of an octogenarian Haida woman, her narrative presents a picture of an individual operating in a culture neither traditionally Haida nor fully Canadian, a culture undergoing tremendous change, yet intelligible and meaningful to one living in it.

The Haida had been exposed to Christianity for only about twenty years when Florence Davidson was born in 1896, and just fifteen years prior to her birth the Masset Haida had become reserve Indians. A few Haida were still living in cedar-plank houses when she was born. The female puberty seclusion was still practiced during her adolescence, and marriages were, as a rule, arranged. Her life spans the beginning and end of a resident Indian Agency in Masset, the development of schooling from the one-room mission school through the residential boarding schools to the modern public educational system, and the evolution of transportation from the dugout canoe to daily jet service on the Queen Charlotte Islands.

Florence remembers a time when the ceremonial button blankets, devised probably in the 1850s by native people, were disdained and her grandmother cut the small buttons from hers to give to her granddaughters for their babies’ clothes. Today Florence Davidson has become perhaps the foremost Haida button blanket maker, sewing exquisite appliquéd blankets from her grandson Robert’s patterns. She recalls the time in 1932 when William Matthews took his uncle’s place as town chief of Masset without a semblance of a traditional installation ceremony. Forty-four years later when Oliver Adams succeeded his uncle, William Matthews, he hired Florence Davidson to cook for the feast; she sang a Haida song in his honor and was recognized for her efforts at the potlatch marking his chieftaincy.

There were no totem poles carved during Florence’s childhood, save the few commissioned of the last of the old carvers at five dollars per foot by museum collectors. In 1969 Florence and Robert Davidson gave a potlatch honoring the erection of the pole their grandson Robert had carved for the Masset people. In short, Florence Davidson’s life weaves through a significant period of Haida culture history, a time that saw the disappearance of many traditional practices (the puberty ceremony, arranged marriages, most forms of potlatching) and the rebirth of others (such as the visual and performing arts).

RECORDING THE LIFE HISTORY

My only special preparations for the journey to Masset in January of 1977 included packing a wool shirt and rain slicker, a tape recorder and forty hours of tape, a journal, a copy of Murdock’s Our Primitive Contemporaries, which contains a chapter on the Haida, and Clellan Ford’s life history of Charlie Nowell to show to Florence Davidson as an example. I had not given extensive thought as to how we would proceed, confident that the problem would resolve itself once I arrived in Masset. My only worry was that I might have the same experience as anthropologist Nancy Lurie, who secured in her first brief session with Mountain Wolf Woman, the Winnebago woman’s entire life history (Lurie 1961: XIV). Luckily I need not have worried: “I’m full of stories yet,” Nani pronounced about halfway through the project.

The quickest method of getting to Masset is to take a jet from Vancouver to Prince Rupert and from there a float or amphibious plane to New Masset on the islands. No matter how rough the weather, I never fail to enjoy the forty-five minutes from Prince Rupert to Masset. Ten minutes in the air, from a point not far out to sea, one can see in the distance the long dark tongue of Rose Spit licking the waters of Dixon Entrance. Minutes pass; the sand bluffs of the east coast of Graham Island make their appearance and the familiar landmark of Tow Hill rises several hundred feet into the air from the sands of North Beach. Geologists call Tow a volcanic intrusion; the Haida say he has a brother up Masset Inlet with whom he quarreled and that is why he stands alone now at the eastern extremity of the islands.

Button blankets worn by Florence Davidson (left) and other Masset Haida (photograph by Ulli Steltzer)

The plane flies over the ancient beach ridges ancestral to the present sands of North Beach and along Tow’s backside. Yakin Point, where Tow paused in his westward migration, intrudes into the cold waters of Dixon Entrance, and beyond I recognize Kliki Creek where Nani, my anthropologist friend Marjorie Mitchell, and I went to collect spruce roots in the summer of 1974. We cross the mouth of Chowan Brook where Nani and her mother used to pick crabapples.

Ten miles from Masset is the “elephant pen,” the local name for a Canadian Forces communications installation whose circular wires and fences look incongruous against the spruce and sand. The plane crosses the village of New Masset giving a glimpse of the Forces base and housing, the new hotel with the only beer parlor for miles around, the high school, the government wharf, the Co-op store. Water splashes the belly of the plane as it descends into the waters of Masset Inlet. Grudgingly, it struggles up on land coming to rest beside the tiny air terminal.

Haida Masset is three miles from New Masset and every taxi driver knows how to find Florence Davidson’s house, or just about any other local house for that matter. Each time I return to the village, I mentally tick off the changes in its facade. Since I have been coming to the islands, the village has expanded as far southward toward New Masset as available reserve land will allow. It now moves westward, into the piled-up stumps of once timbered land. In January of 1977 traces of bright blue paint that adorned the exterior of Peter Hill’s little house in 1970 had been washed away by the frequent rains, Alfred Davidson’s fine large home had burned to the ground, Joe Weir’s house had been razed to make way for a more modern one, the Yeltatzies had added a large picture window to the side of their home, and a rental duplex had been built catty-corner to Nani’s house.

The taxi turns down an unpaved side street and comes to rest just short of the Anglican Church and Robert Davidson’s magnificent totem pole. Despite the external changes in the village, Nani appears little different to me than she did in 1975 or in the years I knew her previous to that. She waits in the open door and enfolds me in a warm hug as I set down my suitcase.

Nani lives alone now in a sprawling one-story house, originally designed and built with the comforts of a large family in mind. Her front door opens into the spacious “front room,” constructed as in other older Masset homes large enough to hold the entire adult population of the village. The front room has seen numerous feasts and potlatches, but normally it contains couches and overstuffed chairs pushed against its perimeter. The Sunday dining table sits in the room’s center; plants fill the front window, and Robert Davidson’s Haida designs, family photos, and religious mementos adorn the walls. Five bedrooms open off the large central room at its far end; at the opposite end, a leaded-glass door leads into the parlor—remodelled between January and June of 1977—panelled and carpeted in thick red plush. Many of our summer taping sessions were held in the quiet softness of this sitting room.

My favorite spot in the house and the room where I have spent the most time is Nani’s expansive kitchen. I mark the passage of my Masset visits by the additions to her kitchen: new appliances, a new shelf, new flooring, a different color scheme. When I first came to Masset in 1970, the wash was done on the back porch in a wringer washer and Nani used to lug the heavy baskets of wet clothes across the yard to hang on the long clothesline, but by 1975 the old machine had been replaced by a new spin washer and dryer (gifts from a daughter and son-in-law), which occupy a prominent position in the kitchen. The village has had electricity since 1964 (and before, if one counts the portable generator that lighted the church and vicarage). Freezers and refrigerators followed in its wake, dramatically altering old patterns of food preservation and storage. Nani’s kitchen contains both of these appliances, and a second freezer, filled to the top with venison, herring roe, berries, and fish, sits on the back porch pantry.

The most eye-catching feature of Nani’s kitchen is the long bank of open shelves along one wall, which display some two hundred bone china cups and saucers, plus everyday dishes and the mugs from which we drink our breakfast coffee and afternoon tea. An oaken table, one of the few pieces salvaged from a house fire in 1952, faces the large kitchen window. In many ways this table is the focal point of the household. At it most meals are taken, visitors are received and served tea, and here Nani sits to rest from her baking or to weave a cedar bark hat. I have spent much of my fieldwork time here, too: interviewing Nani, writing in my journal at night, drinking coffee and gazing at the ever-moving waters of Masset Inlet, talking with Nani and others over tea.

By the summer of 1977, however, the view from the table had changed. I recorded the change, somewhat petulantly, in my journal.

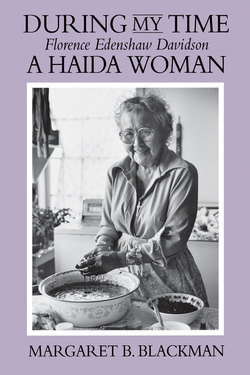

Florence in her kitchen (photograph by Margaret Blackman)

I always liked sitting here and writing, looking up now and then to see Hannah (who lives next door) going in or out and collecting my thoughts as I watched the changing configurations of the western skies. But now a plank ledge runs the length of the window and the foliage of some fifty African violets sitting on it obscures much of the view. A fuchsia hangs from the ceiling and its embrace with a leggy geranium blots out Emma Matthews’ house ….”

Even the long plank could not contain all the products of Nani’s amazing green thumb; I discovered yet more African violets atop the washing machine, their leaves aflutter when the machine entered its spin cycle.

Nani’s house is seldom inactive, and then only for a relatively short period, as she typically retires at 11:30 and arises as early as 5 A.M. Usually there are other boarders; various children, children-in-law, and grandchildren drop by during the day, and the health aide stops in on her rounds of the village. Hannah Parnell and Dora Brooks, Robert Davidson’s lineage nieces, and Carrie Weir, a sister’s daughter, appear every day or so to visit and have tea; and, not infrequently, someone from New Masset comes by to introduce a visiting friend to Nani.

Nani’s tremendous energy is evident in the wonderful creative confusion that pervades her home. On a typical day loaves and loaves of bread rise in the kitchen under the protective covers of fresh linen towels; the combined vapors from a pot of stew and the kettle of “Indian medicine” beside it on the stove mingle and steam the kitchen window; an unfinished cedar bark hat stands spiderlike on the front room dining table; a small cat darts under a chair rustling the wide dry strips of cedar bark draped over it; Nani’s crocheting lies where she left it on one of the front room chesterfields; the kitchen radio blaring messages to people in remote mainland communities competes with “The Edge of Night” emanating from the television in the front room; in the smokehouse adjacent to the house, Nani hangs halibut fillets on racks above the smoldering alder fire. Such was the setting in which Nani related her life story to me. Why she agreed to relate it is the result of several factors, among them her familiarity with anthropological inquiry, the compatibility of the life history mode with Haida values, and, not insignificantly, her relationship to me.

From the time she was very young Florence Davidson was aware of the interest of outsiders in Haida culture and artifacts. Her father worked for C. F. Newcombe of the Provincial Museum in Victoria as an informant and artist, and Florence recalls Newcombe’s many visits to her father’s home. She is too young to have had personal memories of John Swanton, who relied upon both her father and her uncle as informants and resided with the latter during his fieldwork in 1900–1901, but she may have heard them speak of him. In the later years of her marriage the Davidson home was frequented by the occasional anthropologist. Wilson Duff, for example, interviewed Florence more than once about her father and his forebears, and Mary Lee Stearns visited the Davidson home several times in 1965–66 to interview Robert Davidson during the course of her study of contemporary Masset culture (Stearns 1975, 1981).

Following the death of her husband in 1969, Florence emerged as a knowledgeable elder in her own right. In addition to her work with me, which began in 1970, she served as an informant on Haida ethnobotany for Nancy Turner in 1970 and 1971 (Turner 1974). In 1974 Florence was one of several Haida elders who contributed data to Marjorie Mitchell for a multi-media curriculum project on the Haida. In the early 1970s Florence worked briefly with linguists Barbara Efrat and Robert Levine of the British Columbia Provincial Museum, and since 1975 she has served as a linguistic informant for John Enrico, now a permanent boarder in her home. Moreover, she has appeared at museum openings as an elder ambassador of her culture, publicly demonstrated her skills at basket and button blanket making, and welcomed into her Masset home countless friends of white friends interested in Haida culture and eager to learn something of it from this grandmotherly representative.

In a brief life history of Flora Zuni, Panday cautions that the life history is not a natural or universal narrative mode among American Indians, noting that “Pueblo traditions do not provide any model of such confessional introspection” (1978:217). I am not certain if the life history is a Haida narrative form, but certainly as an anthropological form it is compatible with Haida traditions. The phrase used repeatedly by Florence Davidson during the course of her narration and selected by her as the title of this work—“during my time”—is a free translation of an often used Haida time referent, di ؟eneng ge gUt ən di Unsɨdɨng, “I see it [or, I know it] all of my lifetime.” Such personalization of events goes hand-in-hand with the well-known emphasis in Northwest Coast culture upon the individual. The importance of rank, the feasting and potlatching that encouraged competition and individual expression, the custom of acquiring newly invented names at potlatches, and the mortuary potlatch as a vehicle for formally remembering a person long after his or her death (see Blackman 1973), all exemplify the significance of the individual in traditional Haida culture. Though Florence lamented the ordinariness of her life, the question “Why would anyone be interested in my life story?” understandably never arose.

Finally, although some anthropologists, such as Kluckhohn (1945:97), have regretted the intrusion of the anthropologist into the native life-history document, it goes without saying that the relationship between anthropologist and life-history subject is critical to the telling of the story in the first place and ultimately to the understanding of the final record. I agree with Brumble, who notes that “much of the fascination [with life histories is] a result of, rather than in spite of, their being so often collaborative” (1981:2).

Florence Davidson and I come from different worlds and different generations. Her children, the welfare of her family, and the church have been the focus of her long life; I have no children and at the center of my life is my academic career. She has lived the life of a housewife and mother, and I have not. How strange I must sometimes seem to her, spending long periods of time far from home, traveling freely, childless at an age when I should have a large family of my own. “How’s your big family,” she often teases me when we talk long distance. I once asked her what I might do to show I had “respect for myself,” an important Haida virtue. “Dress up and stay home,” she retorted, with laughter in her eyes. Yet our cultural, social, and age differences are softened by the mutual respect and affection we have developed over the years of our collaboration and friendship. My own grandmothers, strong, creative women and important figures in my childhood, did not survive into my adulthood. In many important ways, Nani has filled that gap in my life. Her life history was given to me, I think, as an anthropologist dedicated to learning the “old-fashioned ways,” as a granddaughter curious about a grandmother’s past, and as a woman interested in the events and people that shape women’s lives. I doubt that Florence Davidson could have comfortably related her life history to me before I had established my commitment to learning about her culture, and I am certain that she could not have told her story to a man.

Although I had written Nani regarding arrangements for the project, we did not discuss it in any detail until my arrival in Masset. That first night I indicated to Nani that it would be nice to include what she knew about her ancestors. She thought for a moment and began relating how her father and grandfather had seen lucky signs in the woods, how her mother and her mother’s mother’s sister had been rescued from the smallpox epidemic, and how her grandfather had been called to take the chieftainship at Kiusta. When I protested that I had not yet unpacked my tape recorder, she replied, smiling, “It’s OK, I was just practicing for tomorrow.”

The following day she deliberated for some time about where to begin her narrative and settled on the drowning of her brother Robert, which occurred one month before her birth. From that point on, however, there was little chronological order to the narrative. Often she would select a topic to initiate the day’s recording: “Let’s talk about when my mother and I used to go for spruce roots”; or, “Did I tell you about the time when we built this house?” On other occasions she would leave the decision up to me, asking, “What shall we talk about?” or commanding, “You ask me questions.” I would then pick a topic from the growing list I had compiled since my first day into the project.

When Nani was bereft of life-history memories we would explore kinship, reincarnation, Haida names, and numerous other ethnographic topics that I felt I had not sufficiently covered in my previous research. To a large extent my own interests biased the life-history data I obtained. For example, my concern with Haida ceremonial life, modern Masset’s primary link with the past, led me to inquire repeatedly about feasts and potlatches given by ancestors and relatives. My interest in pollution taboos resulted in a lengthy digression into puberty and pregnancy proscriptions and male/female separation, topics that were not of as much interest to Nani. Because missionaries long ago had discouraged the custom and imposed European standards of decorum upon the Haida, Nani was somewhat embarrassed to discuss her puberty seclusion knowing that the account might be published. I, on the other hand, felt the subject significant enough to pursue until she had exhausted her memory. In addition, my view of life history as retrospective led me at certain times to ask questions that might elicit reflective responses. Typical examples include: What makes you happiest? When are the saddest times? What are the biggest changes you have seen? What would you most like to be remembered for? How would you describe yourself? Accordingly, Florence’s “Reflections” (pp. 136–38) consist primarily of answers to questions that I posed.

Understandably, Nani sometimes dwelt on topics that were of great importance in her own life but not of as much interest to me as an anthropologist, in particular the impact of the church on her life, her role in it, and the meaning of Christianity to her. I do not know what form the life history might have taken had I avoided any intrusion, but given our relationship that would have been impossible. The final narrative is a measure both of our collaboration and of our sometimes divergent interests.

The schedule of our work was dictated by Nani’s daily routine and the time constraints of my short field visits. We worked in the morning, the afternoon, sometimes after dinner, and occasionally just before bedtime. Most of the time we were alone, and when visitors called, our work was put aside. Often after a long day Nani lay on a chesterfield in the front room and I sat on the floor holding the microphone toward her. Sometimes, to avoid the noise and activity of the kitchen, we retired to her bedroom; she sat on her bed and leaned back against the wall, crocheting as she talked, except on Sundays when she put her handiwork aside. At times she wove on one of her cedar bark hats at the dining table. Once I taped her as she whittled cedar splits to be threaded through the black cod she was preparing to smoke. A song she sang on that occasion is punctuated by the sound of metal cutting red cedar. I sometimes joined her in activity. In January 1977, she gave a memorial feast in honor of her sister’s daughter from Seattle who had died the preceding November, and we tried to tape in the kitchen amidst the preparations. Nani filled tarts with raspberry jam and I punched a plastic pattern into fourteen dozen doughy buns while we discussed earlier feasts. The quietest, most comfortable place to talk, though, proved to be the front parlor, where we worked during most of the June 1977 session.

Place or context played a considerable role in triggering Nani’s memory. As we sat at the kitchen table one January day, the rain pelting the kitchen window reminded her of q’ən dleł (“everything’s scarce”), the traditional Haida term for this time of year; a discussion of the seasons followed. Baking bread one Monday morning Nani recalled the days when she used to bake in the summertime at North Island for the fishermen. A juvenile eagle that scavenged a piece of drying halibut in June reminded Nani of her first attempt at slicing halibut and the chiding she received from her step-grandfather for the jagged-edged fillets she had hung to dry. Sometimes discussions of the project with other villagers brought to mind events from the past. Emma Matthews once reminded Nani of a play wedding they had staged as children. Some topics were easier for Nani to discuss than others. She recounted deaths in the family and the events leading to them in great detail, but when I asked her to describe the village and certain villagers as she remembered them from childhood, the details were sparse. I once asked her to describe her aunt, Martha Edenshaw; puzzling a moment over my request, she pointed to a photograph on the wall and answered, “She looks just like her picture.” “But how do you think of her?” I continued. “I think of her just like the picture,” Nani responded unhesitatingly.

Margaret Blackman and Florence Davidson, 1979 (photograph by Anna Franklin)

Nani was aware of numerous gaps in her narrative. When I talked to her on the phone between my infrequent visits to Masset, she would often say, “after you left I remembered lots of things. I wish I could write them down because I forget them.” Subsequent visits in 1978, 1979, 1980, and 1981 brought more reminiscences, but undoubtedly there are events and thoughts that she might wish to include which have eluded her memory. Occasionally, too, Nani was unable to remember something in the detail that I would have liked, reminding me quite appropriately, “It wasn’t important to me then; how was I supposed to know that white people might be interested in it years later?”

From time to time, Nani’s mischievous sense of humor crept into our work. Discussing her father’s house where she had spent her childhood, I asked what it was like inside. She retorted that it was five stories, had “spring beds,” and was covered in thick, thick carpeting. “I’m getting crazier than ever—what if you write that down,” she said, dissolving in laughter. I recorded the contexts of all our taping sessions in the daily journal I kept, a practice I have always followed in fieldwork. Later, the journal became invaluable as I tried to remember what the house looked like that June, why Nani recalled this or that on a particular day, or why a certain subject had been sparingly discussed.

Florence Davidson’s narrative is a circumspect one. Though she related to me both off and on tape things she did not wish to appear in print, her recollections by and large are devoid of the petty jealousies and rivalries that are part of the fabric of Masset life. There is little mention of the misdoings of self and others: illicit sexual liaisons (which figure prominently in some native male life histories4), witchcraft, or feuds between families. “I don’t tell everything—what’s no good,” she said. Throughout our work Florence was conscious that the final product was to be a public document, though I imagine she was more concerned about its public status within her own community than in the larger world. This consciousness clearly guided not only what she related but how it was related. This bias may be characteristic of autobiography, regardless of culture. Jelinik, for example, speaking of autobiography in the Western tradition, notes:

Irrespective of their professions or of their differing emphases in subject matter, neither women nor men are likely to explore or reveal painful and intimate memories in their autobiographies…. The admission of intense feelings of hate, love and fear, the disclosure of explicit sexual encounters, or the details of painful psychological experiences are matters on which autobiographers are generally silent. [1980:10, 12]

The division of the narrative into chapters is an artifact of my own thinking, not that of Florence Davidson’s, although I did discuss its organization with her in the summer of 1978, and the chronology closely parallels the traditional life stages distinguished among the Haida. Nani requested that I edit the narrative to “fix it up” and “make it look right.” I rearranged the narrative in chronological order, made certain grammatical and tense changes, and deleted redundancies, but those who know Nani will recognize her style of speaking. A section of the original narrative is presented in the appendix so readers may see its unedited form. Unfortunately, neither the original transcription nor the final edited version can adequately capture Florence Davidson’s personality—the inflection of her words, her accompanying gestures, her sometimes subtle, always gentle humor, which was often turned upon herself. Nani related her life history in English, interspersed with Haida words that I knew, and now and then she repeated an English sentence with its Haida equivalent.

Following my two trips in 1977, I returned twice to visit and work with Nani as the manuscript progressed through stages of completion. In August of 1978 I took with me the completed introductory chapters and rough version of her narrative. As I typed the narrative portions in July I was astounded at the growing list of questions I was amassing. The project had supposedly been completed the preceding summer, but I found I had neglected some basic life-cycle topics: how long mothers typically nursed their children, the significance of menopause for Haida women, the learning of sexual behavior, and others. In addition, I had enumerated questions dealing specifically with Nani’s life history, such as whether the first children of Isabella and Charles Edenshaw had been born in a traditional house and where Isabella and Charles had lived after they were first married. Fortunately, I secured answers to most of my stock of questions during a week’s return to Masset in August of 1978.

With the manuscript complete except for the Discussion and the Afterword, I returned in the summer of 1979 for another week. This time my main purposes were to check the large genealogy I had constructed and to read Nani’s narrative to her. In addition, I sought her reflections on friendship, growing old, the changes she had witnessed, and the people she has admired. In July of 1980 I returned again, this time to work specifically with Nani on Haida kinship, but our tape recordings included some life-history data that have been incorporated into this narrative. My last visit with Nani before the book went to press, in July 1981, resulted in a few corrections and minor additions to the narrative.

ARCHIVAL RESEARCH

A considerable amount of ethnohistorical research both preceded and followed my fieldwork. In earlier trips to the Provincial Archives of British Columbia in Victoria I had surveyed most of the material relating to the nineteenth-century Haida, but had not explored extant twentieth-century materials. During July and August of 1977 and 1978 I researched these materials. Especially significant were two newspapers from the Queen Charlottes, the Queen Charlotte Islander and the Masset Leader, which were published during the second decade of the twentieth century. In addition to presenting local news, the Islander also ran a series of lengthy articles on the Haida during 1911, 1912, and 1913, written by Charles Harrison, a former missionary. Perusal of materials relating to Thomas Deasy, Indian agent at Masset from 1910 to 1924, revealed documents written by a Haida. Alfred Adams, Florence Davidson’s uncle, carried on a regular correspondence with Deasy from 1924, when the latter left the Queen Charlottes, until the time of Deasy’s death in 1936. Deasy’s reports to the Minister of Indian Affairs, published in the annual reports from 1911 to 1920, present a detailed and generally sympathetic portrait of the Masset community.

From research conducted at the Church Missionary Society archives in 1972, I had compiled all the pertinent correspondence written by Masset missionaries from 1876 to 1913; some of this material has contributed to the present volume. The early marriage and baptismal records for St. John’s Anglican Church at Masset, housed in the diocese headquarters in Prince Rupert, provided marriage dates for several of Florence Davidson’s relatives and ancestors, documented Isabella Edenshaw’s births prior to Florence, and pinpointed the baptismal dates for Florence and her sisters.

Ethnohistorical and ethnographic data have been drawn together to form the traditional and historic picture of Haida women in chapter 2. Additional data from more recent historical documents and from my own field journals are interspersed with Florence’s narrative, both to lend a broader perspective to her account and to present a contemporary non-native view of the Haida.

1. Lives: An Anthropological Approach to Biography, which appeared just as this book was going to press, provides an introduction “to the full historical and conceptual development of the life-history method in anthropology … and discusses the relevance of this method to a wider audience” (Langness and Frank 1981:5).

2. Two of the biographies included there are of women: Sarah Winnemucca (Northern Paiute) by Catherine Fowler and Flora Zuni (Zuni) by Triloki Nath Panday.

3. Boas (1943) later eschewed the life history as a legitimate approach to the study of culture.

4. Charlie Nowell, for example, discusses his premarital and extramarital affairs (which he estimates at more than two hundred) quite openly and in some detail (Ford 1941). To what extent this revelation is a product of Clellan Ford’s well-known anthropological interest in human sexual behavior is not known.