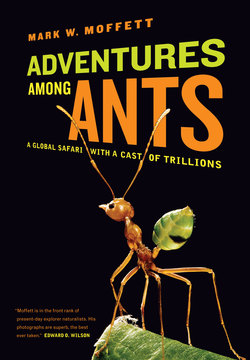

Читать книгу Adventures among Ants - Mark W. Moffett - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 the perfect swarm

At the end of my first week in Singapore I had my first clear view of a swarm. It was late afternoon in a remote corner of the Botanic Gardens. Paddy Murphy sat nearby, smoking a “fag” and examining a silverfish on a tree. I had spent the previous hour on my hands and knees following a trail of marauder ants that were obviously on a foraging expedition, because they were bringing back all kinds of prey. And there, suddenly, near the base of a Brazil nut tree, was a throng of ants—shimmering with the movements of thousands in the cropped grass. I’d caught glimpses of such mobs in my Indian plantation’s understory brush, but here was one open to scrutiny, a band of ants 2 meters wide and over 7 centimeters from front to back. At the back of this band was a V-shaped network of columns 3 meters long that resembled the web of veins in a human hand and, judging by the slaughtered prey being carried along, served the same purpose of conveying nourishment. The web converged into a single column that was the colony’s aorta to the nest. Workers laden with plunder marched along this route all the way home.

Paddy came over and gave a whistle of astonishment. My hand sped across a waterproof notebook as I penciled a sketch of the action. Afterward, examining my drawing, I realized how closely it resembled illustrations of army ant raids. In fact, the swarm compared point for point with descriptions of the most extreme form of army ant attack, the swarm raid.1

In the terminology of army ant researchers, the advancing margin, where the workers meandered ahead of their sisters, is the swarm front. The swarm is the band of ants behind the front, and the fan is the network of columns farther back still, which converge to form the single base column that extends to the nest. Among army ants, swarm raids are peculiar to some New World Eciton and Labidus ants and to a few African Dorylus species known as driver ants. Skirmishes within a raid appear chaotic when viewed in isolation; but when a raid is seen as a whole, a sense of order and even aesthetic beauty emerges.

The phalanx of ants stayed in tight formation. This made the raid’s anatomy easy to pick out—a boon to humans, whose noses are too poor to register the pheromone scents that the ants prefer to use for communication and that bind the raid together. A century ago, Herbert Spencer saw a “closeness of parts” of this kind as strengthening a society’s similarity to an organism. After all, we recognize a dove or rice grain by its boundaries: each has an inside and an outside. The workers that form a marauder ant or army ant raid may be separate creatures, but they do not drift apart, and therefore they form an entity that is not only cohesive but also distinct and well bounded.

The same was true outside the raids, throughout the colony. Over the next weeks I would learn that while trunk trails and their temporary offshoots could extend for a hundred yards, individual marauder ants stay on these roads and seldom travel more than a few centimeters from their sisters.2 All foraging, I determined, is done in a group: my observations revealed no rogue hunters. (I did come upon strays, though. Some were stragglers, sick or lame, on paths all but abandoned. Then there was the occasional isolated worker that was just plain lost. I spent hours watching these individuals stumble around. But even after I gave one lost marauder a bit of my lunch, she had no idea where to go with it. Presumably these forlorn souls wander until they die.)

Certain things became clear to me as I sketched the raid that afternoon in the Botanic Gardens. Within the raiding horde, there’s little appreciable movement of any ant at the swarm front beyond the ground covered by her nestmates—no exploration of fresh terrain except for a stint at the front of the raid, which is the one time in a marauder ant’s life that can be unambiguously described as foraging. The trailblazers at the front (too temporary and plentiful to be considered scouts, they are appropriately called pioneers, as they are in army ants) cross onto new soil. Pioneers don’t appear to be specialists at this task; whoever reaches the front does the job. Nor do they press ahead and fall back with the precision seen in movies depicting Roman soldiers massed against the Gauls. Sometimes they wander a bit. In any case, their actions are restricted to the vicinity of their neighbors, and the raids as a whole have no ultimate destination.

Marauder and army ant raids differ only in degree. One obvious difference is their speed: marauder raids move at a measly 2 meters an hour, maximum, while army ants can travel ten times that fast, the record being 25 meters in an hour. Scale the ants up to human sizes, and that would be over 800 meters an hour for the marauders, versus up to 8 kilometers an hour for an army ant raid. As a result of their slow speeds, marauder ant raids, which last a few hours, cover only 20 meters at most, while over the same time some army ant raids can traverse 100 meters or more.3

A marauder ant swarm raid, based on my original drawing, advancing toward the top of the page.

Workers of Proatta butteli seizing a wasp at the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

In Malayan rainforests to the north of Singapore I would later find a second swarm-raiding Pheidologeton species called silenus, closely related to P. diversus but with raids twice as fast, matching the raid speeds of a slow army ant.4 Sluggish or not, the painstaking searches don’t hinder the hunting prowess of these Pheidologeton species, particularly in the diversus marauder ant, which usually takes food in abundance.

I came to believe that there was simply no need for the mass of marauder ants to move along any faster. In fact, in the Botanic Gardens I came upon a different kind of ant nesting at the base of a withered tree that taught me that mass foraging might not require the group to move at all.5 Lumpy beasts with unimpressive jaws, Proatta look incapable of doing anyone harm. Yet that day I saw three workers grab a wasp that must have outweighed them by a factor of fifty; trying to escape, it nearly lifted them all from the ground in an attempt to take flight. Nearby comrades, attracted by the commotion, seized the quarry by the hind legs. Then more nestmates, perhaps drawn to the site from a distance by pheromones, helped to pull the wasp into their nest.

Groups of the same Proatta ants also killed marauder ants that lagged behind on the base trail after a raid. What accounted for their success? While much of their effort is spent scavenging by themselves for all kinds of tidbits, the Proatta workers accumulate in such numbers within inches of their nest entrances that when an insect walks by, several ants are often close enough to pin it down. Proatta essentially stay in place and let prey come to them, using a group version of the ambush tactic employed by a human duck hunter hidden in a blind, or by solitary-living species such as the snapping turtle, which lies in wait for fish to pass by.6

As we have seen, proximity is not essential for ants to act as a group. But the Proatta behavior demonstrates that, as in the packed raids of the marauder and army ants, a high density of participants increases the likelihood that encountered prey will be caught. When their workers are close together, some ant species are even able to avoid active foraging almost entirely. Ants squeeze together inside their nests, and a Mexican Leptogenys species takes advantage of this density by giving their living quarters a scent that attracts the pill bugs on which they feed. The ants jointly kill and feast on these little crustaceans without leaving home.7

But by keeping on the move in a crowded mass, the marauder and army ants accelerate the odds of encountering dinner, compared to these sit-and-wait strategists. It is the difference between dragging a net through water and leaving it fixed in place. Both methods work, but a motile net almost certainly catches more fish during a given period.

ANATOMY OF A RAID

One morning as I watched the foremost workers in a marauder raid nose their way forward through the grass, Paddy leapt up behind me with an insect net. Suddenly the 12-centimeterlong praying mantis he was chasing landed with a shudder within my swarm. Paddy backed away with a mild expletive as the ants overcame the mantis. Some grabbed the wings by their edges and spread them out to their full green glory, while others took its head between their jaws until it cracked open like a nut seized by pliers. Soon the marauders were slicing and dicing the mantis with the cold efficiency of slaughterhouse employees.

Army ants, and particularly swarm-raiding army ants, are exceptional for their ability to consistently trap difficult, even dangerous, prey. I now saw that this attribute applied to swarms of marauders as well. To uncover the secrets of the marauders’ predatory success, I began to study the moment-by-moment organization of their raids. By watching where the ants first advanced at the front and then doing a slow scan back to the base column, I discovered I could treat what I saw along the way as a chronological sequence. In practice, this wasn’t necessarily straightforward. While the workers might be fearless with prey, they are skittish when it comes to other interruptions. They will retreat from a simple breath of air. To interpret their behavior, therefore, I stood as far off as possible. At times I used binoculars, once confusing a group of birdwatchers with my concentration on what must have appeared to be barren earth.

The ants in the narrow swarm behind the raid front seem to move randomly, going backward, forward, and sideways with respect to the front. There obviously must be a net movement ahead to account for the raid’s progress, but it’s hard to detect ants following one another in that direction. Few trails are evident, and the ants appear to be moving through a diffuse cloud of orientation signals. The swarm advances to new ground every few minutes, and the land it formerly occupied is taken over by the forward part of the fan as more ants begin to form columns by running along specific tracks. The fan is differentiated from the swarm by the fact that it has these columns, and where that demarcation is made depends on the observer’s ability to pick them out. Farther back in the raid, the columns become fewer and busier, with an increasing proportion of ants on identifiable routes. Ultimately, at the back of the raid, the ants funnel onto one path, the base column.

Roughly speaking, each part of a raid has a different function, turning the ants collectively into a food-processing plant. Prey is located by the foragers at the front, subdued within the swarm, then torn up in the fan. From there, it is transported along the base column to the trunk trail and delivered to the nest, where most of it is ingested by the ants. Things aren’t always so clear-cut, of course; as when kids crisscross the same ground on an Easter egg hunt, it is possible for workers in a swarm to find something the lead ants have missed, or for those in the fan to contact prey that’s on the run from the other ants.

Mass foraging permits workers to flush prey and act in concert to catch it, like sportsmen engaged in a fox hunt but with the scale of operations increased a thousandfold. The downside of the ant stratagem is that the colony has to pack its greatest resource—its labor force—into an entity compact enough to cross a small area, instead of spreading those workers far and wide on individual search missions, as would a solitary-foraging species. The result is that the same number of workers finds less, but catches more.8 How? The deployment of these ants maximizes the capture of quarry too large for solitary species, yielding an intake of food that compensates for the slow encounter rate. All ant colonies stash a reserve of workers in the nest, to draw from as needed. Marauder ant swarms are made up of such assistants, transplanted from the nest to the site where food has been discovered.9 Keeping a reliable labor supply close at hand means that a raid can quickly respond to changing conditions—an essential component of success. Prompt conscription to the battlefront through explosive recruitment minimizes the time between the moment when workers first find prey and the arrival of reinforcements to pounce on it. No matter how fierce or capable the quarry may be, with no opportunity to make a getaway it will generally be overpowered by the rapidly escalating force of its assailants.

In his book on military theory, The Art of War, Sun Tzu recommended this stratagem in the sixth century B.C.: “Rapidity is the essence of war; take advantage of the enemy’s unreadiness, make your way by unexpected routes, and attack unguarded spots.”10 The marauder ant, in its raids, has mastered this strategy beautifully.

HOW RAIDS BEGIN

The only time marauder ants are motivated to leave their manicured avenues and raiding paths to strike out as independent individuals, rather than in a coordinated raid, is in the face of disaster. Whenever I trod on a trail and mangled a bunch of ants, both the workers I panicked and their dead and damaged comrades released pheromones causing widespread alarm. The agitated survivors, whom I call “patrollers,” rushed about in a frenzy, dispersing up to a third of a meter from their trunk trail. Each appeared to take her own path away from the trail rather than tracking those around her. The patrollers seemed to be in a frantic search for the source of the problem and would give my leg a serious chew if I didn’t notice them in time.

Self-portrait, after stepping on a marauder ant trail near Malacca, Malaysia.

Unless I bothered them further, all the patrollers would make their own way back to the trail within fifteen minutes. However, after stepping on marauder ant trails hundreds of times, mostly by painful accident, I noticed that on occasion a weak column would emerge from the bedlam and remain active much longer, advancing away from the trunk trail and branching here and there. Supplied with more ants pouring off the trunk trail, a minority of these columns would expand gradually into a wide, fan-shaped swarm raid that often reached 2 to 3 meters across—the largest I measured was 5 meters—and contained troops that pressed forward in concert. At this point, the ants no longer seemed to be looking for me but were again expanding out in a regimented hunt for food. So what began as a response to a footstep or possibly to a tree branch that had crashed onto a trail had transformed into mass foraging in epic proportions. Indeed, the more food the workers came upon in their journey, the more epic the raiding response seemed to become.

This was different from army ant behavior. Marauders raid both in columns and in swarms, with an occasional column expanding into a swarm raid. Army ants typically raid either in columns or in swarms, but not both. Most army ant species are column raiders, whose raids stay in narrow columns from start to finish, whereas swarm-raiding army ants spill directly from their nests in a broad swath, and the raid continues as a swarm throughout.11

What triggers the marauder ants to launch a raid? Though there is no scout to shepherd a raiding party toward any particular meal, I noticed that when a patrolling worker fell by chance upon some morsel, nearby ants converged on the site immediately—suggesting that the worker who made the discovery had released a pheromone—and with their arrival a new pathway soon formed. This episode of conventional recruitment to something tasty could escalate into a raid when an excess of ants coming to the meal continued to advance in a column beyond it, a response known as recruitment overrun.

Was food necessary to the process? Determined to get closer to the truth about how raids develop, I set up camp one weekend, coming as close as anyone has to roughing it in the Singapore Botanic Gardens. A tent would have called attention to myself, so I didn’t bring one. In any case, my intent was not to sleep, or even to move from one spot. All I needed was a camp chair and a stockpile of grub—Grainut cereal, fruit and cheese, and jerky. Stationing myself just far enough away from a 50-meter trunk trail so as not to disturb the action, I watched a 2.7-meter-long segment of the route for fifty hours straight. The midday sun left me roasted. During the second night, a storm waterlogged my notes. But it was worth it. Twice during that period I saw a raid start spontaneously, with a column of marauders streaming out from the trunk-trail throughway without food or provocation. If that had been typical for the entire trail, the colony would have been spawning a raid every forty-five minutes.

I still needed to get a picture of how the raids related to each other. For a week, Paddy joined me at the Botanic Gardens to help me find out what the marauder ants were up to in the long term, in their choice of raiding locations. We mapped raids by marking each path with bamboo skewers emblazoned with neon-colored flags. Within days, the ground around the trunk trail resembled my back after my one session with a Singaporean acupuncturist.

Most often, the raids crisscrossed the belts of land flanking the trunk trail. That is where the pattern became clear. Marauder ant raids moved readily both over virgin soil and across or along the course of prior raids, even ones from a few hours earlier. When a raid passed over an abandoned path, the foragers at the front seldom showed a change in conduct, neither avoiding it nor turning to follow it. On occasion, a raid seemed to retrace an old path a short distance; presumably, there’s a latticework of residual scents from an old raid that must dissipate with time. But in general, each raid went its own way.

This differs from the activities of most ants, such as the seed-harvesting ants of the American Southwest. At first glance, the masses of harvester workers might be mistaken for an army ant raid as they pour out of their nest each day. Actually, though, they are less an advancing army than commuters caught in a traffic jam, reestablishing a trail to areas where they will then scatter to unearth seeds by foraging in the desert sand. Marauder raids resemble those of army ants in not being based on set courses; these mass foragers aren’t obliged to retrace their steps, and they easily cross unfamiliar terrain. The actions of the individual workers may be severely limited, but those of the raid as a whole are not. This is foraging in the pure sense, invoking the freedom to search unknown terrain, in this case moving as one.12

MAKING SENSE OF ANT SCENTS

A year and a half into my Asian sojourn, I made my way by train and bus from Singapore to the island of Penang, Malaysia, where I stayed for a month at a delightful research station on the beach. On several occasions, and with little warning, I was asked by the station manager to vacate my bungalow with its one small bed: a VIP from the American consulate required it for the weekend with his twenty-something “daughter.”

Thus evicted, I would take the opportunity to travel to another rainforest site on the island that was thick with marauder ants. Curious about how the ants communicate to stay in tight formation, on these excursions I studied the marauder ant’s ability to produce chemical trails. With a field microscope, I dissected workers to extract two organs associated with their rudimentary sting: the Dufour’s gland and the poison gland, both known sources of pheromone signals in other ant species. I used a fine forceps to tease free the ant’s infinitesimal glands: thin, translucent sacs small enough to be an amoeba’s luncheon treat. I then smeared the contents on the ground near processions of marauders, to lead the ants where I wanted them to go.

As I hoped they would, the workers dutifully followed the artificial runways. But their reactions indicated that the functions of the two glands differed. They followed the Dufour’s gland trails steadily and accurately and for a long time, which suggests that its secretion is critical in establishing trails, especially stable ones like a trunk trail. By contrast, their response to a crushed poison gland was to run like mad and sloppily follow the route for several seconds. Their brief excitement suggested the poison gland’s contents were reserved for inciting ants to capture prey or destroy an enemy.

This wasn’t enough evidence to produce a set of sound scientific conclusions, but workers engaged in raids were too sensitive to my presence to allow for experiments on them. From watching the workers follow the scent trails I had drawn, I hypothesized that a marauder ant raid is prompted by two trail signals, as has been proposed for army ants as well. The majority of the routes within a raid must originate when workers at the front deposit exploratory trails: pheromones, likely derived from the Dufour’s gland, released as a forager moves on a new path.13 In addition, the workers in the vicinity of food lay recruitment trails that yield a massive response if the quarry—perhaps struggling prey—is attractive to many ants. Networks of columns materialize within the raid fan even when there is no food, however, suggesting that workers reinforce a selection of the trails from the front lines.14 This would lead eventually (I hypothesize) to the accretion of Dufour’s gland secretions into the base trail, and eventually, if that trail continues to be used and reinforced over time, into a trunk trail.

Recruitment signals come and go as food is harvested. The ever-present exploratory trails are the glue that binds individuals into a foraging group, the closest parallel in ant societies to the adhesives that join the cells of our bodies. The front-line workers’ pheromonal scents keep the foragers immediately behind them close together and moving ahead as a unit, all the while leading the raid forward.

For both the marauder ant and army ants, the varied attributes of the raids—the cohesive advance, the lack of a target other than the general land ahead, the absence of scouts—seem unrelated. But these features are manifested in a simple series of actions so circumspect and tentative that in humans they might be equated with separation anxiety. Unless they are diverted to kill prey en route, the ants are committed to a single goal: to follow fresh trails leading ultimately to unexplored terrain. Each ant stays near her sisters on routes that draw her inexorably out from the nest and onward, eventually bringing her to the raid front. There, she encounters the first land that is barren of signals. In response she runs ahead, drumming the unmarked ground with her antennae and depositing a smear of pheromone that guides those behind her. She then returns hastily to her “comfort zone” within the pheromone-saturated land behind. Such timidity is crucial to keeping the troops functioning as a unit, the equivalent of human boot-camp training. It vividly contrasts with the pluck the same worker shows when she joins the wanton melee around prey.

In the marauder ant, as in army ants, every worker is in effect shackled to a nexus of social signals generated largely by individuals who happen to be nearby. Thus it is not so much the proximity of individuals but their lack of autonomy that makes the army and marauder ant superorganisms nonpareil. No matter how much individuality may be prized, there may be times when, for a society—ant or human—to function productively, it pays to march in lockstep.

OTHER ANIMALS THAT HUNT IN GROUPS

There are other members of the animal kingdom that mass forage. Some spiders are sit-andwait socialists who weave a communal web. The more spiders, the larger the catch, with dozens bearing down to secure, say, a large moth.15 Harris’s hawks of New Mexico hunt in families of up to five, leapfrogging between perches until they see a rabbit. Then they converge for a simultaneous kill or attack it in relay. If the quarry finds cover, one or two hawks flush it out while others wait in ambush.16 Among mammals, lions, wild dogs, wolves, and killer whales also hunt in groups, staying in range of one another while seeking prey too large or agile for them to catch unassisted. Some bacteria move in similarly voracious swarms called wolf packs, with pioneers advancing and retreating in army ant style.17 By secreting enzymes together, they can digest prey far larger than a lone bacterium would have any chance of killing.18

Species that bring down large prey are not the only ones that forage as a group. Many bird species can mix together in a flock that, according to Ed Wilson, “behaves like a giant mower, leaving a pattern of well-trimmed areas juxtaposed to relatively untouched areas.”19 While birds act separately to glean insects, in a flock they can take advantage of their companions’ guidance to avoid enemies such as hawks and to track the best bug-hunting locations.

Mass foraging can also be a tool for mass transit, as with cellular slime molds. After they eat an area clean of bacteria, hundreds of thousands of amoeba-like cells join together to produce a sluglike creature that resembles a blob of petroleum jelly. This slug can journey far greater distances than a single amoeba and can pass over pockets of air between grains of soil that would stop the lone amoeba cold. As it goes, the slug sheds individual amoebas, which feed on the local bacteria.20 The slug is searching not for food, however, but for areas of low moisture and high illumination, where it casts off spores.

Another group, the “true” slime molds, grow by the expansion of one amoeba into a fan-shaped body called a plasmodium, which hunts for decaying matter. In high school, I kept an orange species that resembled a swarm raid shrunk to a few centimeters across. If there was little food, my pet crept over its Petri dish slowly but steadily. A sizable bonanza could bring it to a halt as it set about gorging itself; if a patch of food was more modest, part of the slug gathered to eat while the rest continued searching, its fanlike front reduced. A slime mold isn’t as dumb as its brainlessness suggests: one variety can find the shortest route through a maze.21 I admit, though, that a person must be very patient to find it interesting as a pet.

Some of the most army ant–like strategies are deployed by vegetarians. Workers of a few termite species spread out in a loose network while foraging, each walking ahead a centimeter or two and laying an exploratory trail before she retreats and another takes her place. The advance resembles the progression of a marauder ant raid, though it’s less methodical and more dispersive than cohesive.22 A forager who detects wood at a distance, likely by scent, will abandon its search and move straight to the food. Usually she explores the wood alone, then lays a recruitment trail back to the nest. Being defenseless and easily dehydrated, termites expire fast when lost. Staying in the columnar networks helps them find their way back home and hastens the construction of the galleries the termites require to survive on exposed ground.

Another vegetarian engages in mass hunts that have a protective as well as a nutritive function. Whereas an unaccompanied eastern tent caterpillar can easily lose its grip on a tree, several together will lay a silk mat that engages their feet and keeps them from falling. These leaf eaters then find meals in a procession, with the pioneers pushing ahead short distances before retreating, to be replaced by the ones behind.23 A group can follow an old silk trail or strike out over new terrain. A lone caterpillar finding satisfactory greenery will lay an especially attractive—perhaps chemically stronger—recruitment trail back to the silk tent housing the colony, in some cases drawing out the entire population.

This is where all other animals that search for food in groups differ from ants like the marauder: whether caterpillar or bird, bacterium or wolf, individuals are fully capable of moving away from the pack or flock and foraging without companions. And with rare exceptions, “alone” in these species really means alone, because few animals have the capacity to recruit assistants from a distance. A few birds and primates call one another to food: for example, in Africa chimpanzees draw others to bonanzas of fruit in trees by uttering loud hoots, and pied babblers lead their novice fledgling offspring to feeding spots with a “purr” sound.24 But such social actions are virtually unknown in most species, where signals such as the yelp of the coyote or the singing of whales more often function in maintaining appropriate spacing between individuals, in combat, courtship, or group bonding, or to keep pack members together when they are on the hunt, than in calling in the troops.

One rare exception is the naked mole rat, an African rodent with antlike colonies that include queen, small worker, and soldier castes. The worker rodents lay odor trails to the root tubers their colonies feed upon.25 Another remarkable exception, involving a symbiosis between animals who have little in common, is the raven, who will call out to guide wolves to prey; the wolves share the prey with the ravens after the kill.26

COMPARATIVE MARTIAL ARTS

Even though marauder and army ant campaigns are directed at predation rather than military conquest, the byzantine structure of their pillaging and the frequency with which they do battle with other ants make it tempting to conceive of their “armies” in martial terms. Predation and combat have been linked in human history as well, the tools for one often serving handily for the other, with battles occasionally ending in cannibalism.27

Swarm raids compare neatly to the deployment of Roman heavy infantry and other early battalions that swept forward in a broad front. One Roman innovation was to spread troops a bit more widely than did previous armies, which gave each man a few square meters in which to defend himself. Though their workers are never far apart, marauder and army ants similarly tend to remain a few body lengths away from each other, right up to the front lines, a spacing most likely maintained by the ants in order to avoid treading on one another.28

Naturally, there are differences between the Roman armies and ant armies. Roman troops fell into formation only in times of active conflict, when soldiers on the front lines served as a defensive shield against another army open to view, protecting the soldiers behind them and slowing the advance of the opposing army before them. Among marauder and army ants, in contrast, the foremost workers serve as a contiguous search party to flush out prey. Rarely are the ants’ opponents arranged in a similar configuration; rather, they are discovered and overtaken in sporadic fights.

Despite their tactical responsiveness to prey, marauder raids can seem regimented when compared to the flexibility of Roman legions. Deployed in formations arrayed three deep, the Roman troops could be reconfigured in response to changes in an enemy’s assault. The phalanx might be preceded by cavalry that harried the enemy in advance, for example, or by scouts sent ahead to report on the lay of the land so that the day’s plan could be adjusted accordingly.

My painstaking observations of the marauder ant raids left me with several unanswered questions. Animals as diverse as wolves, birds, and bacteria are able to mass forage in organized groups and then to move off in isolation. Why aren’t marauder ants and army ants similarly able to employ long-distance scouts to assist in their concentrated raids? The risks a marauder or army ant scout might face would seem to be no different from those encountered by any kind of ant that searches on her own, entering a hostile world without backup. Wouldn’t the rewards, for the group, far outweigh the risk to the individual?

Perhaps risk has little to do with it. Watching the marauder ants cart off fruit, seeds, and animal prey, I suspected that the unpredictable quality of their plunder simply made such reconnaissance pointless. Or maybe any tendency for an individual ant to scope out her surroundings—and in so doing wander off on her own—somehow interferes with the mass-foraging process, in which a total fixation on tracking the pheromones of the group is key.

Humans are accustomed to supervision and chains of command that encompass every level from presidents to petty administrators. Roman soldiers wheeled and charged under the direction of officers moving through the ranks. For certain ants, too, transient leadership roles do exist, in some circumstances—as with the successful Leptogenys scout I observed in India, who always stayed with the assembled troops, guiding them to the termites she found. What, then, of the leadership role of individuals in a marauder ant raid?

Once, at the Botanic Gardens, I attempted the near impossible: to follow an individual marauder minor worker entering a swarm raid. I picked her out because she was missing the end of one antenna. It was too difficult to focus binoculars on her, so I tied fabric from an old T-shirt across my face to keep my breath from disturbing the ants and got in close. I followed “Stumpy” for a minute through the tributaries of workers in the raid fan. She dashed wildly for a moment near the commotion of ants on a beetle larva—agitated, I surmised, by alarm pheromones released from the poison glands of the struggling workers—then kept going. Approaching the raid front, she wandered and finally entered a stream of ants, where I lost her.

Nowhere along her route did I observe other individuals guiding her, or her influencing other workers. As with army ants, the marauder ant is a species with no established leaders. If I could communicate “take me to your leader” to one of them, it’s unlikely I would be shown the queen, who, like all ant queens, lays eggs but coordinates nothing. Nor does any of her workers inspire, cajole, or force the whole army to take a line of action. Proverbs 6:6–8 makes this point: we must “go to the ant” and “consider her ways, and be wise” because she does the job without “guide, overseer, or ruler.” King Solomon must have been a devoted ant observer to reach this conclusion. In all likelihood, he grew up watching Messor barbarus, the dominant seed harvester of the Mediterranean, which indeed “gathers her food for the harvest,” as the Bible tells us.

The hardworking ant described by King Solomon was likely a solitary-foraging seed harvester ant such as this Messor barbarus from the Kerman region of Iran.

A century ago, Harvard’s erudite ant scholar William Morton Wheeler called army ants “the Huns and Tartars of the insect world.”29 But no myrmecologist has ever identified a Genghis Khan or Attila among them. At best, an individual in the raid may be momentarily better informed than others, giving her a brief and local influence.30 That could happen when a worker at the front sends out recruitment signals to prey—but even then she is likely to be acting in concert with nearby sisters. No ant, in fact, can conceive of the raid in its entirety, know where it is going, or anticipate how the masses will respond when food is found or enemies encountered. A raid arises through a series of simple actions by each worker and others like her, in an engagement that can truly be described as “self-organized.”

Humans constantly have to work around issues of self-interest that would otherwise impede the emergence of social institutions and infrastructure. Our clannish devotion to networks of kin and friends has proved particularly problematic in the context of modern warfare. The solution has been to divide armies into squadrons small enough for the troops to bond and be willing to take risks for one another.31 Ant workers, of course, don’t recognize nestmates as personas in the way I picked out the stump-antennaed individual,32 and they never throw themselves in harm’s way so that particular compatriots might live. What we perceive in ants as acts of heroism and devotion are really more akin to acts of patriotism. Since it is only the superorganism that matters, ant workers instinctively toil and die for the benefit of the colony, without recognition or recompense other than the remote possibility of augmented reproduction by the queen, the one member of the group who is indispensable. Mortality seems to be the basis of the domestic economy for prodigious, combat-savvy ant societies.33 It is difficult not to think of the Spartan mothers who sent their sons off to battle saying, “Come home either with your shield or on it.”34 Brute force, apparently, is the key to tactical success for mass-foraging marauder and army ants.