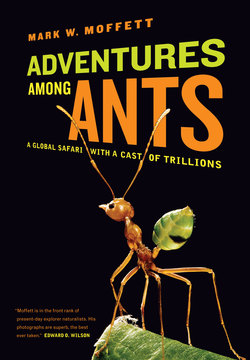

Читать книгу Adventures among Ants - Mark W. Moffett - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеa brief primer on ants

Anatomically, ants are like other insects in having three primary body sections: head, thorax, and abdomen—though the addition of a narrow waist gives ant abdomens extra mobility, enabling a worker to, for instance, aim a stinger or repellant spray from her rear end.1 Almost every ant has pores near the rear of the thorax through which two metapleural glands discharge phenyl acetic acid and other fungicides and bactericides, required for a healthy life in the soil.

Ant antennae are elbowed at the midpoint so they can be manipulated like arms, though unlike the individual’s jaws, often called mandibles, they can’t grip. Ants keep their antennae moving for the same reason that we scan with our eyes: to monitor the environment. Beyond their elbows, antennae are flexible and endowed with sensors for touch and smell, senses more valuable for most ants than sight. An ant’s compound eyes use many adjacent facets to produce images that are put together by the brain into a mosaic view. The eyes of most ants have little resolving power, though there are certain exceptions: inch-long Australian bulldog ants are so visual that I’ve watched them station themselves near flowers and seize bees out of the air.2

Mandibles are the prototypical tools used by ants to manipulate objects, and they are toothed in different ways to serve the needs of different species. Many ants can also grip eggs with spurs on the foreleg above the foot, in much the way that squirrels hold acorns with their paws.3 Each foot, called a tarsus, is flexible and multisegmented and clings to surfaces not with toes but with two terminal claws and cushiony adhesive pads.

A Thaumatomyrmex worker at Tiputini, Ecuador, using her long-toothed mandibles to hold her bristly millipede prey while she strips off its hairs before eating. These tiny, solitary foragers are notoriously hard to find.

Ants are highly social. They are classified in the order Hymenoptera, as are wasps and bees, and some of these insects, such as the honeybee and the yellow jacket, are highly social as well, as are all the members of another insect group, the termites.4

The smallest known ant colonies, of at most four individuals, are those of the minuscule tropical American ant Thaumatomyrmex.5 Colonies in the tens of millions are typical of some army ants of the African Congo. Supercolonies, like those of the Argentine ant currently battling for exclusive control of southern California, have populations in the billions.

Ant sociality, like that of the social wasps, bees, and termites, is expressed through a division of labor in which offspring that do not reproduce, called workers, assist their mother, called the queen, in caring for her brood, their future siblings. Despite the characterizations of Disney and Pixar, any ant recognized as an ant is female; males do exist, but they are socially useless and resemble wasps rather than ants.6 When I call an ant “she,” therefore, I’m simply reflecting reality. During their brief lives, males perform a single duty: they fly out of the nest, mate with a virgin queen (often several mate with one queen), then die. The queen will live much longer, starting her own nest and producing offspring for years from the sperm collected in this one mating flight. Because ant colonies are meant to be permanent, she and her workers, who live anywhere from a few weeks to a couple of years, will stay together. The only exception to this rule occurs when the workers rear the next generation of queens and males that depart their mother’s nest to produce the next generation of colonies. When a colony’s queen dies, with some exceptions we shall see later, the colony dies with her: her workers become lethargic and gradually expire.

In large part because colonies contain relatives, ants are altruistic, working without focusing on their own prospects for reproduction, which in any case are usually near zero. Edward O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobler further argue that colonies can be unified beyond familial bonds, as happens with humans. This allows for the success of colonies in which workers have multiple parents, including more than one queen.7 That’s not to say there can’t be discord in a colony. Among some ants, for example, workers, though unmated, can lay eggs that develop into males. Such workers form a pecking order in which those at the top forage less, receive more food, and are more likely to lay eggs.

Instead of maturing gradually, like a human, an ant hatches into a larva, the stage during which growth occurs; after a quiescent pupal stage, the adult ant emerges. A female ant’s size and accompanying functional role (or caste, such as queen, minor worker, or soldier) are largely determined by how much food she is fed as a larva, though temperature has an influence at times, and genetics can also nudge a growing individual toward a specific function.8 Queens and workers (and different workers in polymorphic species) are distinctive in appearance because body parts develop to different extents depending on the individual’s size. Adult ants do not grow, but workers tend to perform different tasks as they age. Young adults, identifiable by their paler color, remain in the nest and take on the lion’s share of the nursing responsibilities (in most polymorphic species these are handled by the minor workers), cleaning and feeding the larvae and, in species in which the larvae spin silk encasements before transforming into pupae, helping the adult ants emerge from their cocoons.9

In addition to being highly social, ants are global, native to every continent except Antarctica and residing in virtually every climate. They have achieved universality by conquering Earth’s most abundant habitat: the interstices of things, including the most secluded portions of the leaf litter as well as pores in soil, cracks in rock, and gaps and hollows in trees, right up to their crowns. As ants sweep through and conquer, they force other small animal species to the fringes of this prime real estate.10 Ants sprang to prominence at the end of the Mesozoic Era, as the dinosaurs neared the end of their reign and when flowering plants first exploded in number, providing generous and distinctive crannies suitable for ant foraging and habitation, not to mention tasty seeds, fruit, and other edible plant parts and the insect prey that feed upon them. Housed and fed for success, ants have reigned over the landscape ever since.11