Читать книгу Adventures among Ants - Mark W. Moffett - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 infrastructure

Through my camera lens, I closed in on a gray Diacamma worker with an elegant silver sheen striding along with what appeared to be a sense of purpose. I tracked her ascent of an embankment of soft soil. She went over the top and landed squarely among marauder ants following a trunk trail on the other side. Six minor workers pinned her in place as workers laden with food retreated; then a major arrived and executed her with a crushing blow, discarding the corpse just off the trail, where several minors buried her in the dirt as their food delivery operations resumed.

Marauder colonies maintain a fast, steady, well-protected flow of food and labor on their trails. Whereas small ant colonies, like people in small societies, are able to access and distribute the supplies they need without roads, larger groups depend on an infrastructure so complex that in the marauder ant it rivals human highway systems. The idea of a superorganism applies here, of course: whereas a microscopic organism like a microbe can rely on simple diffusion to distribute nutrients through its body, a large one, such as a human being, needs a circulatory system.1

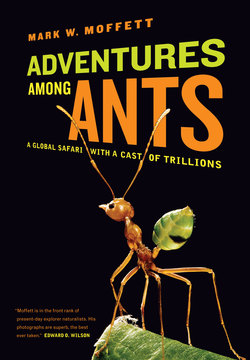

A marauder ant major worker hefting a Diacamma ant killed after intruding on the colony’s trunk trail. The discarded corpse was buried by the minor workers.

ROADS

Marauder colonies avoid both gridlock and species confrontations, like that with the Diacamma worker, when trails are in good shape. Highway construction efforts are part of the society’s logistics, providing supply lines for fresh combatants on the front lines as well as streamlined routes for bringing home the plunder.2 Trunk trails are well looked after—that’s how they can be distinguished from the fleeting paths created by raids.

Each worker size class participates in the creation of the roadways. All the castes eliminate surface irregularities along a trunk: while the medias and majors chisel out embedded roots and pebbles, minor workers extract grains of soil, establishing the road’s slightly concave shape in cross section. The dross is discarded along the edges of the trail, where it accumulates in embankments like the one the Diacamma walked over. When the ground is moist, the minor and media workers build up the ramparts into a complete soil cover, or thin-roofed arcade, fabricated from soil extracted from the trail surface or from mining shafts—blind-ended tunnels near the trail used specifically as quarries.

Members of the construction crews expend their efforts foraging for building material rather than food. It is likely that no communiqués pass among them.3 Rather, like compulsive bricklayers unable to go by an unfinished wall, passing ants respond to the ongoing building project, and the structures emerge without any active collaboration. The portions of the walls that are suitably positioned and shaped along a trail attract the most attention from passersby bearing soil bits. As a result, the arcades rise to completion where they are most needed, without a blueprint, and damage to them later is repaired without fuss.

Accomplishing large projects without communications is called stigmergy. The marauders’ approach to building has been duplicated by robotics experts, who have discovered that it’s cheaper and easier to achieve a goal such as piling up small objects with a group of simple robots responding to the work done thus far than with one large, more intelligent robot.4 Stigmergy is at work in such websites as Wikipedia and Google as well, where many people add their insights to the statements and choices of others.5

Major workers of the marauder ant serve the role that humans reserve for heavy-duty construction equipment. I have called the largest of these individuals “giants” since the day I first saw one lumber from that nest in Sullia to the cheers of Mr. Beeramoidin and other forestry officials. Imagine a man and an elephant working together to build a road; the size difference between the giant and the minor worker is nearly ten times that great.

Relatively scarce, the giants tackle jobs that, though infrequent, require their prowess. While the smaller ants are so omnipresent that their jobs invariably get done, removing just a couple of giants from the work crew can cause a trail to degrade.6 Fallen objects such as twigs and leaves snarl traffic and must be cleared for the roadway to remain open for use. When one of these giants arrives at such an obstacle, she pushes beneath it, then lifts her head high while standing on tiptoe. Ultimately, she shoves the object to one side, if not on the first attempt, then on the second or third, in a manner similar to that used by elephants to clear human paths.

When the soil roofs of the arcades sag, the large marauder ants respond to the pressure against their heads as they pass underneath with the shoving technique as well. Captain Charles Thomas Bingham, the Irish officer stationed in Burma, called the majors “the trowels and rammers of the Ant’s Public Works Department.” Their actions raise the drooping arcades and conceivably increase their structural integrity by binding the soil particles. The soil covers are finely granulated on the outside and are smoothed internally by the majors’ battening.

In addition to enclosing their roads, marauder ants build thicker soil edifices over prize fruit or meat bonanzas, structures that facilitate the business of feeding. Workers guard the outer walls while others eat in a narrow gap between this exterior layer and an inner scaffold, which absorbs any moisture in which the diners might otherwise become mired.

Covered-over passages and encased food bonanzas are kept tidiest in areas of dense litter or vegetation that provide physical support so that less caretaking is required to maintain them. To what use is all this effort? Not, it seems, as protection from the elements. The earthworks fall apart in rain, and disintegrate when the earth is dry. Arcades are thin enough to puncture with a tap of a finger, which means a route is weatherproof only when it travels through an underground tunnel, perhaps dug and then abandoned by other animals. Alternatively, near the nest the ants may make a subterranean route of their own: over time, construction crews can scratch away so much soil from the trail surface that the highway sinks from view, at which point the ants seem to be able to construct a thicker, rainproof cover that becomes flush with the surrounding land.

A marauder ant trunk trail with soil sides and partial soil cover, extending through the leaf litter in Johor, Malaysia.

DEFENSE

The main function of this relentless building is defense. Because trunk trails extend for dozens of meters, they travel through territory controlled by other ant species. Marauder ants must therefore be organized to protect the trunk trails from aggressive neighbors or even from hapless passersby such as the Diacamma.

Strangely enough, when the soil ramparts are absent or breeched, the job of defending the trails goes to the most expendable ants in the colony—the maimed and the decrepit. At the spot where I saw the Diacamma killed, a row of minor and small medias stood along either side of the trail, ready to fight off any more of her comrades who might wander by. Marauders darken with age, changing from creamy brown to a dark cocoa color, and I could tell that many of these guards were old from their near-black integuments. Amputees and the infirm struggled to stay upright as they jabbed at additional chance intruders from the Diacamma nest nearby.

Among ants generally, the risks taken by workers tend to increase with age, demonstrating that their long-term value to a colony diminishes as they get older. Months-old fire ants engage in fighting in battles with neighboring colonies, for example, whereas weeks-old workers run away and days-old individuals feign death.7 The old and wounded marauders often serve in the worst occupations, such as trail guards. They also throw garbage from the nest onto the community refuse heap, or midden, where they work until they fall over, their bodies joining the rest of the colony’s waste.

For the marauder colony bothered by Diacamma, all the fuss over the contentious stretch of trail became moot within hours, after an arcade had been completed: the Diacamma workers could now walk over the trunk trail, blissfully ignorant of the industry below them. If a trail should sink underground, it is as protected as a passage in an army bunker, safe even from human footfalls.

Bulwarks constructed over trails and provisions prevent battles among competing marauder ant colonies as well. Where they are absent, combat can last a day and engage thousands of minor workers, which pour along the line of contact between the armies. Sometimes the tangle of ants stretches a meter wide. Compared to the free-for-alls that erupt during prey capture, the fights unfold with extreme care. At first the minor workers examine each other more like dancers than combatants. Brawls begin when pairs interlock mandibles, then grapple for several minutes before disengaging and maneuvering for better position. Fatalities escalate as additional workers pull on one of the locked ants. Fighters can tuck their hind ends beneath their trunks, making it difficult for others to grasp them at their fragile waists. Meanwhile they wave their abdomens in an action called stridulation, in which a ridged surface like a nail file on the undersurface of their abdomen rubs against a scraper located below their slender waist to produce a rasp like the sound made by strumming a comb; it is barely audible when a large worker is squeezed lightly and held up to the ear. This may be a call for help, though ants, being deaf, detect the rasps only as vibrations through the substrate. After some minutes of struggle, one of the ant’s limbs will pop off like the arm of a medieval torture victim stretched on the rack. Slowly, surely, the workers pull each other apart.

Among ants in general, most lethal fights are variants on this hand-to-hand combat. Some species avoid prolonged tussles, instead taking a hit-and-run approach, inflicting damage fast and then dashing away. Many of these use a sort of chemical mace, spraying insecticides from their abdomens. Otherwise ants have not developed techniques to safely inflict damage from a distance—a development in human conflict that began with the invention of the spear. In one remarkable exception, workers from cone ant colonies stop their opponents from foraging by surrounding the enemy nest and dropping stones down the entrance and onto their heads as they attempt to leave, a nonlethal, but effective, technique.8

Which marauder ant colony wins? One especially sizzling afternoon in the Singapore Botanic Gardens I conducted an experiment with bottles of spray paint. By spritzing a different neon color lightly on the traffic moving along the trunk trail, I was able to mark a small portion of several colonies’ worker populations. Three days later I came upon a battle between two of the nests. Scanning the thousands of grappling ants, I watched as the pink colony’s larger battalion eventually swamped the greens, which retreated. With only a hundred casualties on both sides, there was no further commotion. In fights between honeypot ant nests in Arizona, special “reconnaissance workers” move through the battlefield to assess the size of the opposing armies, then draw out more troops or organize a hasty retreat depending on the situation.9 I have no idea if that’s how the greens “knew” to give up—that the odds were against them. But at some point, the green army clearly decided to leave the field of battle rather than fight on.

Because marauder ants lack scouts that could monitor intrusions around their nest, conflicts among them have little to do with territoriality—the control of land. Fights occur only by accident, when one colony’s raid contacts the raid or exposed trail of another, and may be avoided, even near a foreign nest, when trails are sealed over. Because the size of a marauder ant army is likely to increase the closer the battle is to its nest or to the food it is defending, the colony with the most at stake usually swamps the other and wins.

THE NEST

Like most ant species, the marauder ant is a central-place forager, meaning its food supplies are funneled to a single central nest, which houses the queen and her brood. It is here that the society invests most heavily in defense, which makes excavating a marauder ant nest excruciating for scientist and insect alike.

But I had to do it. Studying marauder ants without looking in a nest would make as much sense as studying people without looking in a house. I also knew the ants well enough not to take my first attempt at snooping into their home lightly. Thinking the whole business out in advance, I selected my combat gear: long pants, a long-sleeved T-shirt, a pair of tightly woven socks, and tough boots. Arriving at the Singapore Botanic Gardens, I tucked the shirt into my pants and the pants into my socks and advanced toward the nest with a sharp-tipped shovel. Hovering over the nest, I breathed deeply for a moment before slamming the shovel into the earth. I had loosened a tiny chunk of nest soil; immediately a mass of enraged ants poured from the entrances. I threw the soil to the side and dug in again. And again. It took only a few tossed scoops before workers of all sizes had swarmed over my shoes and socks and up my pants and shirt to the first exposed skin they could reach: my neck and wrists.

When I could no longer tolerate the hundreds of bites, I ran to where I was out of range of the nest and scraped the ants off my skin and clothing. Then I grabbed the shovel anew and leapt back into the fray.

Repeating this cycle a few times, I found that the horde of minor workers pouring from the expanding gash in the soil had moved out many meters. Adding to the problem, the ants knocked off my body had spread out to the safe havens I’d used previously. Eventually, I had to sprint away from the nest to find a moment’s respite from the desperate defenders.

The thrill of a dig is in locating the queen. A marauder queen is a good runner, and during the time it takes to excavate a nest she’s likely to have been on the move, which makes it hard to know where she normally resides. On my first excavation, she was cloaked by an entourage of workers of all sizes and as a result—ouch!—a pain to catch.

It is yet another example of the value of media and major workers that battles between their colonies are fought only by the minor workers, while the larger ants—the heavy artillery—enter full combat mode only at the most desperate hour: when the nest is threatened. This distinction makes military sense. In 1914, the British engineer and military theorist Frederick Lanchester proved the advantage of outnumbering the enemy, even using troops of inferior quality, when battles are fought in large-scale formations. Hence, the minor workers, which per capita require little in the way of resources for a colony to rear and maintain, form a kind of “disposable caste” for both combat and predation. During colony conflicts, fights are one on one, making for a battle of attrition in which quantity trumps quality.10

After witnessing an excavation, Paddy Murphy claimed to be in awe of my tolerance for marauder bites. However, the payoff was a delight: I got an inside look at the marauder’s home life. Their nests are often at the base of a tree, where the colony takes over available hollows such as abandoned rodent burrows, cavities left when a root decays, or even buried jars—any space in the earth will do. Suspended among the heaps of workers in these hollows are eggs, larvae, pupae, and victuals such as seeds and legless animal bodies. Also present are smaller, outlying chambers dug by the ants themselves, an activity that results in telltale piles of soil around the tree base. These are near, but typically separate from, the ants’ midden piles of seed husks and discarded insect parts.

In the outlying chambers are the pale callows, adult ants so young their exoskeletons haven’t fully hardened. Here, the young minor workers take on the role of nurses, tending the brood. Also crammed in these chambers are major and media repletes—a special caste in the marauders, distinct from other medias and majors. With their bloated abdomens, repletes serve as living pantries, storing and then regurgitating liquid food to other colony members. (The food is oily, suggesting that repletes take their fill of oil-rich seeds.) Excavating my first nest, I saw the repletes much like fat cells in a human body and wondered how many a colony needed to stay healthy. The question still needs an answer. The repletes’ liquid stores are only a part of their hoarded reserves: workers also stockpile seeds and insect flesh from recent catches. Because repletes’ reserves do not spoil, it is possible they are drawn from mostly in exceptionally lean times.

It’s unclear how individuals are chosen to take on the indolent life of a replete, leaving others to toil outside, but their lifestyles couldn’t be more dissimilar. Repairing trails and mangling prey, “orthodox” medias and majors strut high on their legs. In the darkness of the nest, their replete sisters crawl with their bodies pressed to the ground or bury themselves among the brood, interlinked with the outstretched legs of resting minor workers.

Determining the population of a marauder nest—typically between 80,000 and 250,000 workers—can be an adventure. For an excavation in Thailand, for example, I traveled north of Bangkok to Tam Dao National Park in the company of primatologist Warren Brockelman, who was studying the brachiating ape known as the gibbon. At a station inside the park we heard stories of a local tiger that had grown so brazen that he would leap through open windows and drag out the bodies of his victims. Sleeping that first night in Warren’s open lean-to, I was awakened in the dark by the sound of rumbling breath. At sunrise Warren pointed to tiger prints in the dirt.

Later that morning I joined Warren to watch a pair of pileated gibbons sing a duet in a little valley. Noticing a marauder trunk trail nearby, almost invisible in the heavy leaf litter, I fell to my knees and for over an hour inched along the trail, grateful to forget all those vertebrates, whose simple behaviors, like leaping through windows, made the marauder ant’s superorganized throngs seem all the more awe inspiring, small or not. Oblivious to the time, I continued until I found myself near the crest of a hill. At the crest was the columnar trunk of a dipterocarp tree, and at the base of the tree, marked by the discarded soil and ant trash spilled around its buttressed roots, was the nest, at last! For several heedless seconds, I scrambled around the tree on my hands and knees, in the classic “compromising position.” Then something caused me to look up, and there, just two yards away from me, was a bull elephant. Wrinkled and gray, he stood absolutely still and silent, with his right forefoot lifted as if he’d been about to step forward. For that moment only his eyes moved, the eyelashes rising and falling in a blink. When he turned and crashed into the forest, all I could think of was how unfathomably larger than an elephant I must appear from an ant’s perspective.

After recovering from the unnerving but thrilling encounter, I exhumed the ant nest with a foldable camp shovel, put several kilograms of ants and soil in a plastic bag, and stumbled back to Warren’s jeep, a half-hour away. That evening at the park hostel’s dining room, I convinced the cook to let me put my bag of treasure in the kitchen freezer. I needed to freeze the ants—thus incapacitating or killing them—in order to separate them from the soil so I could make my counts. I went to bed satisfied by a good day’s work.

But the next day a different cook was on duty. No one had told him about my ants, and he’d removed the bag from the freezer and placed it on the floor. The ants had revived, cut their way through the plastic, and stormed the kitchen. I managed to round them up after an hour, enduring countless bites to my fingers. Grateful that my knowledge of Thai curses was meager, I also managed to mollify the new cook with two Singha beers and many compliments on his stir-fried pad see ew.

The painful bites and Thai curses were forgotten once I had tallied the data and gone to relax in the hostel’s dirt-floored canteen, where I ate sticky rice under a ten-watt bulb while trying to impress two girls, on holiday from Australia, with how cool it was to be an entomologist (and when that didn’t work, a National Geographic photographer). But I’d forgotten one of the most important lessons of marauder ant research: one worker always stays behind, after a skirmish, waiting for the proper moment to exact revenge. This time it happened midway through my meal. I started to howl and slap myself, and the girls disappeared.

BREAKING CAMP

Marauder ants are often on the move, and it is here that their roadways again play a role. I have come across dozens of migrations in which the whole society relocates, using the trunk trail for its exodus. Such operations are vaster than any raid. Colony members that normally wouldn’t venture from the nest—every egg, larva, and pupa, every swollen and cowering replete, every delicate callow worker—join a caravan that proceeds as far as 80 meters to a new nest site. The enterprise involves a staggering protective force of workers exploring almost to the span of my hand from the trail flanks. Two to six nights are required, with the convoy taking a break during daylight hours.

Only once have I seen the queen in a migration, and that was in the Malayan species Pheidologeton silenus, which is similar in many ways to P. diversus, the marauder ant. It was near midnight. I had been sitting for six hours in a particularly water-saturated corner of dense rainforest at Gombak Field Station in peninsular Malaysia, watching ants hauling their brood. Suddenly, there she was, part of the convoy, marching along with her stout body and strong legs as if she were designed for a life on the run. Escorting her was a tight retinue of several hundred minor workers. Some of them rode on her body; others ran in a mass a couple of inches ahead and behind her and on each side. The emigration column swelled as she passed, with the entourage flowing at exactly her pace. So quickly I had no time to pull out my camera, she disappeared where the trail led into the dripping brush.

Why move? Changing house can be a time-consuming chore. The honeypot ants of the southwestern United States, who laboriously carve nest chambers into tough desert clays, seem to never move: perhaps their expenditures on home construction are too high. For others, migrations occur only after a dire circumstance, such as the flooding of the nest or attacks by a vertebrate predator. But with the marauder, when I expected a migration to occur, it often didn’t, and vice versa. I documented migrations of colonies that were eating well (in one case, dining on daily servings of bird seed supplied by me) but then inexplicably moved to a barren area. Conversely, colonies often stayed put even after I had dug up part of the nest for study.

The frequency of marauder colony migrations remains a mystery. My best guess is that colonies move a few times a year on average, but because I couldn’t watch colonies around the clock, I could not be sure the colony at a site was the same or had changed since I had last been there. Several times after observing one colony migrate, for instance, I saw another move into its abandoned nest, which made me wonder if the ant colonies were like human families upgrading their homes. One colony moved 8 meters and then two weeks later relocated to its original location.11

Similar to marauder ants, though at the opposite extreme from homebody honeypot ants, are the nomadic army ants, which have been characterized as unique for the frequency, predictability, and organization of their migrations. Describing the transient domiciles of African army ants, the Reverend Thomas Savage reminded his readers in 1847 that “a man’s dwelling indicates the nature of his employment.”12 While the large colonies of other ants require intricate nests, and like large human populations are hard to move, army ants avoid investing in substantial shelters so that they are as prepared to change locations as are Bedouins with their tents. Many army ants use abandoned chambers under objects or beneath the ground, as the marauder ant does.

New World Eciton burchellii army ants take this trait to an extreme: their nests are called bivouacs, because the only physical structures are the bodies of the ants themselves, as a half million or more gather under a low branch and form a hanging, bushel basket–sized mass of interlinked bodies. (Other army ants form similar chains within their underground enclaves.) As Reverend Savage might have predicted from the simplicity of Eciton burchellii encampments, the colonies of this species and a few others migrate with great regularity, every day for weeks at a time. It’s thought that as their armies became more effective in the ancient past, army ants tended to exhaust the supplies of prey near their nest, forcing the evolution of such roaming behavior in response to a recurrent need for fresh hunting ground.13 No surprise, then, that one army ant species has been shown to migrate more often if the colony is underfed.14

The plainly nomadic Eciton burchellii has been a research favorite and has dominated our perceptions of army ant behavior. The evidence suggests, however, that other army ants vary in their nest movements and that the species that relocate in a regular migratory cycle represent the minority. Some early naturalists, who had the luxury (rarely afforded modern researchers) of remaining for years at a site, recorded army ant colonies staying put for many months.15

If my assessment is correct, many army ants may be no more nomadic than the many other ant species that migrate periodically, and sometimes on a regular basis.16 For species with colonies of a few individuals, relocations can commence, as they do with Bedouins, at any provocation, as appears to be true of Myrmoteras trapjaw ants whose nests in crannies in forest litter require little construction. At least some ants seem to be driven to pull up stakes by food requirements or outright hunger. A nomadic mushroom-eating ant in Malaysia, for example, changes its nest most often when its food runs low.17 With the marauder ant, the connection between migration and foraging remains uncertain, but in all likelihood this species doesn’t eat itself out of house and home as often as the more predatory army ant, permitting extended residences in one place. As with other wayfaring ants, when the need for a migration arises, the establishment of reliable thoroughfares to the new nest is the cornerstone of its success.

CREATING A NEW COLONY

Marauder ants and army ants share a common strategy for mass foraging and to some extent a proclivity for moving nests. But they have very different strategies for establishing new colonies. In most garden-variety ants, the young queen flies from her mother colony to mate. The foundress snaps off her wings upon arriving at her destination and then digs a nest chamber. In it, she rears her first crop of workers unassisted. (In some species the queen forages at this stage, but more commonly she doesn’t leave her chamber and survives off her body fat.) As soon as these few ants mature, they take over all the labor and begin the first tentative foraging expeditions, leaving the queen to lay eggs, basically the only task she will accomplish for the rest of her life.

The queen of an army ant colony, in contrast, does not grow wings or fly away. Instead, through a system known as fission, one of the queen’s daughters inherits half the colony and takes it as her own; the other half goes its own way with the original queen. Because even a start-up colony has thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of workers, army ants never have to deal with problems of a meager labor supply. From its inception, a colony can always count on a huge contingent for its raids.18

How marauder colonies get their start, however, is a mystery. This much I know: their queens are tough, and they are excellent runners during migrations, but otherwise they don’t resemble army ant queens in that they do grow wings and fly from the mother nest. After mating, they dig a nest chamber and attach their eggs to a hairless patch on the underside of their abdomens, a behavior unknown for any other ant. They carry the eggs around by tucking the abdomen partially under their bodies, which forces them to stand awkwardly high on their legs.

Unfortunately, despite my repeated, frustrating attempts to observe a colony’s establishment, the queens I managed to follow didn’t survive to rear workers. Nor did I find a marauder “starter” nest, or any nest with fewer than tens of thousands of workers—again, despite many long searches. So this part of my fieldwork remains tantalizingly incomplete. I’m eager to find out how a juvenile colony, lacking multitudes of ants, gets its food. While mass foraging becomes obviously advantageous when there’s a labor force that vastly outnumbers its quarry, perhaps droves aren’t necessary for success beyond that achieved by an ant foraging alone. If ants use a buddy system, even two workers, or at least a small group, might travel together to gang up on prey. Whether the developing marauder ant colony employs such a strategy is at present pure conjecture.

My failure to locate small nests suggests that extremely few new marauder ant colonies survive. Indeed, I often saw young queens, after their mating flight, being killed by workers from an established marauder nest. A queen’s survival likely requires her family to grow swiftly until it has a safely large population—a rare event. Fortunately, we can gain clues as to how colonies mature quickly from the marauder’s relative silenus. At Gombak Research Station, I excavated silenus nests, put the nest soil and all the stray workers in a bag, froze the bag, shook it up, counted all the ants in a tenth of the soil to estimate colony size, and then looked through the remainder of the bag for any queens. My colonies each contained one queen and from 64,000 to 127,000 workers. But I also found a nest of a few thousand workers and twenty-three wingless queens that clustered together amicably. The founding of a nest by a gathering of queens is called pleometrosis. With multiple queens laying eggs, the worker population no doubt increases rapidly, perhaps giving the colony a head start in foraging as a group.19

The diversus queens that I kept together likewise showed no aggression toward each other, though why each foundress attaches her eggs to her own body remains unclear. All the marauder colonies I dug up contained only one queen; if pleometrosis is common in this species, and in silenus, too, the number of queens must decline with time.

In contrast to marauder ants, army ant workers cull their queens before they mate. Typically, they raise several new queens, and when half their number depart with the chosen one to form a new colony, and the old queen goes her own way with the other half, the excess queens, blockaded by the workers, are left behind to die.

It seems the marauder ant workers likewise do the deed of disposing of excess queens, but in their case this occurs much later in the life of the colony. I learned this at the Botanic Gardens as I tallied workers who were repairing a damaged thoroughfare. At one point I noticed a group dragging a dusky object out of the nest and along their trail. Extracting it from them, I found in my hand a wingless queen with the worn mandibles and the near-black pigmentation of an aged animal. She was very much alive but had apparently outlived her usefulness to the colony and was being evicted. Twice more I saw the same event at nests sizable enough to suggest that marauder ant societies can retain more than one queen for a long time. Allowing these workers to finish their job, I watched them abandon the struggling queen at the side of their trail or in the garbage heap.

Calling the female reproductive ant a queen is a poor metaphor because ant royalty does not lead, and unlike human monarchs, they sire their minions. Nevertheless, the two varieties of queens share a characteristic: with royalty comes favor but also great peril.