Читать книгу Adventures among Ants - Mark W. Moffett - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеintroduction travels with my ants

A pale morning in June 4 AM

the country roads still greyish and moist

tunnelling endlessly through pines

a car had passed by on the dusty road

where an ant was out with her pine needle working

she was wandering around in the huge F of Firestone

that had been pressed into the sandy earth

for a hundred and twenty kilometers.

Fir needles are heavy.

Time after time she slipped back with her badly balanced

load

and worked it up again

and skidded back again

travelling over the great and luminous Sahara lit by clouds.

ADAPTED FROM ROLF JACOBSEN, “COUNTRY ROADS,”

TRANSLATED BY ROBERT BLY

My first memory is of ants.

I was down in the dirt in my backyard, watching a miniature metropolis. A hundred ants were enraptured with the bread crumbs I had given them, and they enraptured me as they ebbed and flowed, a blur of interactions. I marveled at how they sped into action when an entrance cone collapsed, or when one found a crumb or wrestled and killed an enemy worker. I could see that ants addressed problems through a social interplay, just as people did.

Years later, I met a group of Inuit children who had been brought by a special program to Washington, D.C., from a remote village in Alaska. Expecting the kids to be awed by the wonders of modern civilization, the welcoming committee was taken aback when the children fell to their knees to gape at a gathering of pavement ants, Tetramorium caespitum, pouring from a crack in the sidewalk. Alaska teems with charismatic megafauna like bears, whales, wolves, and caribou, but these children had never seen an ant. The awestruck boys and girls shrieked with delight as the ants circled and swarmed at their feet.

Ants are Earth’s most ubiquitous creatures. They throng in the millions of billions, outnumbering humans by a factor of a million. Globally, ants weigh as much as all human beings. A single hectare in the Amazon basin contains more ants than the entire human population of New York City, and that’s just counting the ants on the ground—twice as many live in the treetops.1

It’s a part of our psyche, the need to care passionately about something to give one’s life meaning: team sports, a just cause, wealth, religion, our children. Ants and I were destined for each other. As a junior high student back in 1973 I was enticed to join a science book club by the offer of three books for a dollar. One of my choices was The Insect Societies, and it riveted me from the moment I cracked its cover. Even today, its musty, yellowed pages bring a rush of memories of steamy summer days in the small Wisconsin town where I spent my childhood climbing maple trees and snaring crawfish and frogs. The book used a thicket of technical terms like polydomy, dulosis, and pleometrosis to describe ants, bees, wasps, and termites and featured exotica on every page. To me, the activities of these insects were every bit as mysterious as those of the long-lost peoples depicted in ancient petroglyphs. It would be twenty years before I experienced an approximation of that early, tingling thrill, when, in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, I scrambled over shattered rocks in the newly unsealed tomb of Ramses I, carrying a torch so I might find and photograph scarab-beetle hieroglyphs.

The dust jacket of The Insect Societies showed the author, Edward O. Wilson, in a natty dark suit standing in a laboratory at Harvard University, where he was a professor of zoology. “Mr. Wilson,” the jacket said, “has published more than 100 articles on evolution, classification, physiology, and behavior—especially of social insects and particularly of ants.”

I was a practicing biologist long before I acquired that book, however. My parents remember me in diapers watching ants and insist that I called each one by an individual name. When a little older, I cultured protozoa from water samples from Turtle Creek. I bred Jackson’s chameleons—Kenyan lizards with three horns, like a triceratops—and wrote about the experience for the newsletter of the Wisconsin Herpetological Society. One school night during the dinner hour I received a call from a zookeeper in South Africa. Having read my work, he wanted my advice on chameleon husbandry. Mom’s casserole got cold as my family stared at me, a socially insecure fourteen-year-old, explaining over the intercontinental telephone line how to maintain a safe feeding area for newborn lizards.

When I was in my second year as an undergraduate at Beloit College in Wisconsin, Max Allen Nickerson—a scientist at the Milwaukee Public Museum whom I knew from the Wisconsin Herpetological Society—invited me to join him on a monthlong expedition to Costa Rica. I was in heaven, about to live the dream of a boy who grew up on stories of early tropical naturalists. Finally the gear I had gathered over the years could be put to use in the pursuit of science: magnifiers, nets, bug containers, plastic bags for frogs, cloth sacks for snakes and lizards, boots thick enough to stop a snake bite. Over the next two months I helped to catch everything from a Central American caiman to a deadly coral snake.

One day as I wandered alone in the rainforest, lizards squirming in the sack hooked over my belt, I heard a barely audible sound that was subtly different from that made by any creature I had met so far. For me, that sound would prove as portentous as the rumble of a herd of elephants: it was the noise of thousands of tiny feet on the move across the tropical litter. Looking around, I spied a flow across the ground in front of me—a thick column of quickly moving orange-red ants carrying pieces of scorpions and centipedes, flanked by pale-headed soldiers equipped with recurved black mandibles that were almost impossible to remove after a bite. These were workers of the New World’s most famous army ant, Eciton burchellii. Later that same day, I would be awestruck by an even more massive highway of ants, several inches wide, formed by the New World’s most proficient vegetarians—leafcutter ants hauling foliage home like a long parade of flag-bearers.

In the two years that followed I went on treks to study butterflies in Costa Rica and beetles across a wide swath of the Andes, where I spent six months marching over plateaus of treeless páramo habitat and scaling rocky cliffs at 15,500 feet. I began to get a taste for the life of the seasoned explorer.

But I wanted more. I wanted to study the ant.

On returning from the Andes, I steeled myself to write a letter to Edward O. Wilson, whose Insect Societies was still my bible. I got back a warm, handwritten note encouraging me to drop by to see him on my way to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod, where I was about to take a course in animal behavior.

Beloit is a small college. Its atmosphere is progressive and informal, and the students know their professors by their first names. So when Professor Wilson opened his office door, I greeted him with “Hi, Ed!” and gave him a hearty, two-fisted handshake. If my presumptuously casual attitude offended him, he didn’t show it. Within minutes, this world-famous authority and recipient of dozens of top science prizes (he had already won the first of his two Pulitzers) was spreading pictures of ants across his desk and floor and exchanging stories with me as if we were boys. We talked for an hour, and I left with my head full of ideas for fresh adventures.

When I was a child, my heart was with the early explorer-naturalists. I studied the adventures of the insightful Henry Walter Bates and Richard Spruce, the brilliant Alexander von Humboldt, the groundbreaking Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin, the wildly eccentric Charles Waterton, and the incomparable Mary Kingsley. I admired these brave field scientists for their appetite for adventure, and I envied them their era. In the nineteenth century, entire regions were still uncharted. Most of Borneo, New Guinea, the Congo, and the Amazon were still labeled unknown. By the time I started exploring, in contrast, most of the Earth had been mapped and claimed, although since then I have managed to set foot in a few places where no outsider—and in the case of Venezuelan tepui mountaintops, no person—had ever walked before.

But I also read the books of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, George Schaller, and other living field scientists. I had lunch at Beloit with Margaret Mead, who banged her cane for emphasis as she recounted her experiences with exotic tribes. I recognized in these scientists a sense of adventure grounded, like that of the early naturalists, in a desire to know the unknown—but not by conquering it, as some early naturalists had, but rather by understanding it. Their fervor was infectious. John Steinbeck captured the attitude perfectly in The Log from the Sea of Cortez, a chronicle of his adventures in the Gulf of California with his longtime friend the biologist Ed Ricketts: “We sat on a crate of oranges and thought what good men most biologists are, the tenors of the scientific world—temperamental, moody, lecherous, loud-laughing, and healthy.”

That’s what I wanted to be.

When I arrived at Harvard in 1981 to begin graduate school under Professor Wilson, my first priority was to find a species worth studying for a Ph.D. in organismic and evolutionary biology. I knew where to search for ideas. Harvard is famous in scientific circles for its collection of preserved ants, the largest in the world. Located on the fourth floor of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, where the profusion of mothball crystals was rumored to keep the entomology professors alive to a ripe old age, it had been founded in the early twentieth century by the legendary myrmecologist, or ant expert, William Morton Wheeler, and later expanded by the equally legendary William L. Brown Jr. and Edward O. Wilson. (After finishing my degree, I was privileged to spend two years as curator of that collection.)

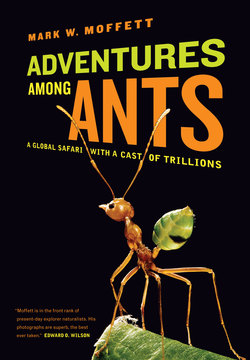

A scanning electron micrograph of the marauder ant Pheidologeton diversus depicting the normal behavior of a minor worker riding on the head of a major. There’s a 500-fold difference in body weight between these two workers.

One day I spent hours rummaging through hundreds of the naphthalene-scented cabinets searching for the least-understood specimens. From childhood, I have had an eye for all that is quirky in the natural world. In those cabinets, accordingly, I was drawn to the ants with oddball heads and mandibles, curious body shapes and hairs. I wondered what their bodies said about their lives and habits.

Continuing my search the next day, I came upon three drawers labeled Pheidologeton, a name I had never heard before. The glass tops of the drawers were dusty, and their contents were in disarray. The dried specimens, glued to small wedges of white cardboard that in turn were affixed with insect pins to foam trays, had obviously not been looked at for many years.

I was struck at once by the ants’ polymorphism—that is, how different they were from one another in size and physical appearance. As in most ant species, the queen was distinctive, a heavy-bodied individual up to an inch long. But it was the workers that gave me an adrenaline rush. While the workers of many species are uniform in appearance, in Pheidologeton the smallest workers, or minors, were slender with smooth, rounded heads and wide eyes. The intermediate-sized workers, or medias, had larger, mostly smooth heads, and the large workers, known as majors, were robust, with relatively small eyes and cheeks covered with thin parallel ridges. The wide, boxy heads of the majors were massive in relation to their bodies, housing enormous adductor muscles that powered formidable mandibles.

I had never seen anything like this. The minor, media, and major workers didn’t look like they belonged to the same species. The heads of the largest workers were ten times wider than those of the smallest. The biggest majors, which I came to call giants, weighed as much as five hundred minors. The energy and expense required to produce these giants—and to keep them fed and housed—must, I thought, be immense, which meant they must be of extraordinary value to their colonies. I left the collection that day certain I had found something special: few ants display anything close to the extreme polymorphism of Pheidologeton.

As a student I knew that the best-studied polymorphic ants were ones I’d seen on my first trip to Costa Rica—certain Atta, or leafcutter ants, and New World army ants such as Eciton burchellii. These ants have some of the most complex societies known for any animal, giving them an exceptional influence over their environment. Their social complexity is due in part to the division of labor made possible by their varied workers, which, with their differing physical characteristics and behavior, can serve different roles in their societies. Called castes, these classes of labor specialists focus variously on foraging, food processing or storage, child rearing, or defense, such as when large individuals serve as soldiers. Given its minor, media, and major castes, I suspected that Pheidologeton would be a treasure trove of social complexity.

From reading the books of Jane Goodall and other modern naturalists, I had developed the view that the best path to a career in biology was to find a little-known group of organisms and claim it, at least temporarily, as my own. I could then, like an old-fashioned explorer studying a map in preparation for a voyage, pinpoint those regions most likely to yield rich scientific rewards. Buoyed by this belief, I decided Pheidologeton would be my version of Jane Goodall’s chimpanzee.

I soon found that my point of view was outdated. All around me, starry-eyed students who had come to biology because they loved nature were becoming lab hermits, indentured to high technology. Watching my fellow students, I realized that too much of modern biology represents a triumph of mathematical precision over insight. Sure, laboratory techniques allow for unprecedented measurements, but what good are those streams of numbers if it is unclear how they apply to nature? One thing I’d already absorbed from Ed Wilson was that much could still be done with a simple hand lens and paper and pencil. I was determined to spend my life in the field.

In the fall of 1980, I proposed to Professor Wilson that I would journey across Asia to investigate Pheidologeton—which I confidently proclaimed would be among the world’s premier social species. My enthusiasm, if not my charts and graphs describing the species’ polymorphism, won him over. I received his blessing and, within days of passing my oral exams, boarded a plane bound for India. Over nearly two and a half years I would visit a dozen countries without a break, vagabonding through Sri Lanka, Nepal, New Guinea, Hong Kong, and more.

Since then, ants have led me to all the places I dreamed of as a child. That’s far more than can be described in a book, and so I focus my narrative on a few remarkable ants. I start with the marauder ant, taking my time both because this species was my own introduction to ants and because it exemplifies behaviors that come up repeatedly, such as foraging and division of labor. Thereafter, subjects are organized, in a crude way at least, by the ant approximations of human societies throughout history—from the earliest hunter-gatherer bands and nomadic meat eaters (army ants), to pastoralists (weaver ants), slave societies (Amazon ants), and farmers (leafcutter ants)—ending up, at last, with the world-conquering Argentine ant, with its hordes of trillions now sweeping across California.2

In this book, I will consider what it means to be an individual, an organism, and part of a society. Ants and humans share features of social organization because their societies and ours need to solve similar problems. There are parallels as well between an ant colony and an organism, such as a human body. How do ant colonies—sometimes described as “superorganisms” because of this resemblance—reconcile their complexities to function as integrated wholes? Whose job is it to provide food, dispose of waste, and raise the next generation—and what can ants teach us about performing these tasks?

To find out, let’s begin our adventures among the ants.