Читать книгу TOGETHER THEY HOLD UP THE SKY - Martin Macmillan - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Tears Follow Laughter

ОглавлениеIt wasn’t just the west that experienced “the Sixties”. China also had its version of sweeping political and cultural changes during that turbulent decade. Coincidentally, 1960 happened to be a leap year, but the vast famine that starved an estimated 20 million people as a result of Mao Zedong’s disastrous ‘Great Leap Forward’ policy to modernize the economy meant that the decade of the 60s started out as nothing short of catastrophic. “Struggle hard for three years. Change the face of China. Catch up with Britain and catch up with America” was the unrealistic slogan. It’s no wonder that the Chinese people warmly embraced a newly released comedy film called Sister Liu. Having experienced the man-made devastation of the late 50s and early 60s, those lucky enough to have survived finally had something to put a smile on their faces.

Strangely parallel to the folk music revival in the west during their tumultuous 1960s, the Chinese movie Sister Liu was based on a well-known traditional folktale, telling the story of a young girl named Sister Liu whose extraordinary singing ability is central to the plot. But instead of this folk revival being a direct expression of the common people as happened in the west, this film was made in the new Communist China as an instrument to further its ideology. As the original version of the folktale’s story line didn’t match Communist ideology any more, the film’s script writers dutifully recreated Sister Liu as a successful fighting singer who dared to laugh at the oppressive landowner and went on to lead a successful campaign against the rich. So art was used to arouse the Chinese people in a time of great trouble, but cleverly the problem was cast within a model of class struggle to deflect any blame away from the government’s disastrous failings.

In the original folktale, Sister Liu’s life ends poetically and tragically. But at the end of the movie she not only survives but finds true love, a fitting reward for someone with true revolutionary spirit. Sister Liu uses her extraordinary singing talent to rebel against the oppressive rich landowner and his like by rallying the poor peasants together around her. The film makes sure that the rich landowner and his false scholar friends are portrayed not just as evil, but also as arrogant and most importantly as ridiculous. It gave the Chinese audience plenty enough to laugh about.

In several scenes in the film, the precious books cherished by the landowner and scholars, and used to build their case for a strong singing competition with Sister Liu and the peasants, are thrown into the river and all intellectuals invited by the landowner for the singing contest are laughed at by the peasants. In another scene when Sister Liu is kidnapped by the landowner and locked away in his mansion, she and the peasant girl servants smash all of the landlord’s porcelain antique collection. While Chinese audiences were enjoying the comedic porcelain smashing scene, few of them could have appreciated the portentous irony that this particular scene and many others in the film such as the wholesale destruction of books of knowledge soon would be repeated in a few years’ time during the Cultural Revolution. And at that time nobody laughed any more.

In the Chinese calendar, 1962 was the year of the third animal to emerge, the honorable Tiger. According to the twelve-year cycle of animals in the Chinese zodiac, people born in the Year of the Tiger are powerful and courageous, full of optimism and determination. At the same time they are deep thinkers, very sensitive and can have great sympathy for people. As a result of these traits, others hold them in high regard and treat them with respect, despite the fact that they can come into conflict with authority or that their generally sound decisions are sometimes arrived at too late. In matters of the heart, Tiger people are often attracted by independent types who are stimulated by their passion and energy, but who can still manage without them. Tiger people need partners who are constant and steady but who quietly pursue their own plans. They are least compatible with Snakes.

In this particular Year of the Tiger, a girl was born to an ordinary family in the county of Juncheng in Shandong, a coastal province situated between Beijing and Shanghai. Composed of vast agricultural fields of garlic, apples, and ginger, Juncheng county was a small, rural jurisdiction, now part of Heze, and far away from any large cities. At that time most of the area was still without electricity. When the sun set, outdoor activity all but ceased, and families retreated into their small houses until the sun rose again the following morning.

The new baby girl was the first child for the couple, and she was later joined by a younger brother and sister. Government-sponsored family planning had yet to be introduced in China, and people could have as many children as they wished. As Mao said, “more people, more power and more ideas”. This attitude had doubled the Chinese population in just 20 years. In any case, the one-child policy introduced in the late 1970s has only been very selectively applied to urban Han Chinese, so rural and ethnic minority couples, then as now, would still have larger families than the outside world would speculate.

Despite living in such a rural agricultural area, the young couple were not peasants working the land. The new mother was actually a 25 year-old singer. To Chinese standards this was a relatively late age to give birth to a first child. The reason of the late-coming baby in this case was due to the mother’s profession as a singer. She sang in the local opera, one of the popular performances in the rural areas. In vast China, different regions have very different dialects or even completely different spoken languages and singing styles as well; thus dozens of local operas have sprung up and have entertained people for thousands of years.

The new baby girl’s mother sang and performed in one of these local opera troupes which was reputedly a good one. At the age of 25 she was still young, but as a local singer, she was unlikely to make a bigger name for herself, even if she harbored such ambitions.

Hers was not a glamorous job and doesn’t compare to modern show business. The performances would take place outdoors for the local peasants, for a proper theater didn’t exist. They tended to follow the lunar and agricultural cycles with performances at major times of the year such as the Moon Festival or during winter when there was not much else to do in the fields. Perhaps the girl’s mother simply decided that starting a family wouldn’t greatly inconvenience her singing career.

In the past when a new baby was born, the parents would look at the Chinese zodiac in some detail to predict the future of the newborn. And certainly a Tiger child would be cause for some good speculation. But the times had changed. The Communist Party was championing atheism over fatalistic superstitious beliefs. There were no gods, no ghosts, no deus ex machina; everything in the future would depend on your self, your hard work, individually and collectively.

The baby girl’s father, Peng Longkun, also was not a peasant but a local Party official. As such, he must believe in what the Party said instead of other traditions. He had a duty to champion atheism. In fact this was his job for Mr. Peng Longkun was in charge of local cultural affairs. In this rural village he was one of a select few people who lived on a small salary granted by the government. As the Chinese would say, he was “eating the food from the Emperor”, a position envied by millions of peasants who spent their uncertain lives toiling away on the land. Peng’s family didn’t have too much to boast about in material terms, but his relative social status gave his family a sense of pride.

Now that the couple had a child, there were no early signs that the Tiger baby would be so special. What it did mean was that the parents had to work even harder to raise their small family. As soon as the young girl could walk, she followed her mother from village to village as she gave performances. At this early age she heard her mother constantly singing at home and frequently in public. As she got a little older, she could already sing along quite admirably. Her mother’s colleagues said that one day she would replace her mother. Indeed she would, but on a much grander scale than anyone in rural Juncheng could have foretold.

As in most places in the world at that time, rural life in China was tranquil and lived on a small scale. There was no particular aspiration for glory or fame beyond mundane existence. This quiet life would not last for very much longer. By the mid 1960s, far away in Beijing the storm clouds of a new revolution were looming. For the Peng family, and countless others all over China, the coming revolution would make their humble life unbearably difficult. And yet, after the storm’s relentless destruction, their daughter would shine all over China.

In late 1962, several hundred kilometers away in the Chinese capital, Beijing, there was a ten-year-old boy. He was born in the Year of the Snake. The Chinese zodiac tradition tells of the animal race across the river ordered by the Jade Emperor. Just after the Dragon had finished in fifth place because he had stopped to help others by making rain, everyone heard a galloping sound and next a Horse appeared on the shore. But a Snake had hidden itself in the Horse’s hoof, and frightened upon seeing it, the Horse fell back. So the Emperor gave the next position, the sixth, to the Snake.

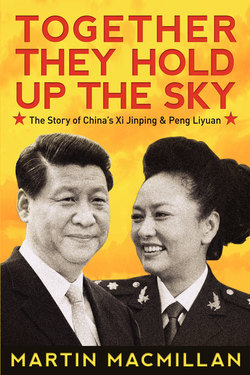

Though obviously cunning, intelligent and wise, snakes are not particularly well-liked by the Chinese. And so in China, the Year of the Snake is often referred to as the Year of the Small Dragon. By way of association, the Snake is thus granted positive attributes of the beloved Dragon and can match any powerful animal, including the Tiger. Enigmatic in its camouflage, self-confident, coiled and poised to strike if need be, the patient Snake can read complex situations quickly, relying on its own instincts and endurance for survival. Twenty-five years later, defying the conventional wisdom of the Chinese zodiac regarding incompatibility, this Small Dragon boy would match up with the Tiger girl to create a most powerful liaison with consequences far beyond their private life together.

To the outside world in China, and certainly compared with Peng Longkun’s humble family in rural Shandong province, the Small Dragon’s family was living the high life in Beijing. The head of the family, Xi Zhongxun, was then Vice-premier of the People’s Republic of China enjoying all the power and privilege of such a high position. The Xi home and household played host to a constant stream of A-list celebrities, among them politicians, scientists, intellectuals, religious leaders as well as the top actors and singers of the time. By the time he was ten years old, the Little Dragon certainly had considerable exposure to what power and position could provide in this seemingly secure and stimulating environment.

But as it turned out, this first Year of the Tiger in his young lifetime didn’t bring any good luck to the Xi family. In fact, all of the family’s glory vanished overnight. The trouble started with just one book, The Biography of Liu Zhidan.

Liu Zhidan had been one of the Chinese Communist revolutionary veterans who was active in the northern province of Shaanxi. This was the terminus of Mao Zedong’s well-known Long March from the south during the civil war with the Nationalists. Thanks to the strong base of local support built up in Shaanxi by Liu Zhidan over many years, the Chinese Communist Party obtained its chance to secure its stronghold in northern China and escape the pursuit of the Nationalists. The People’s Republic owed much to Liu Zhidan and he was accorded the title of a “Founding Hero”. Since Liu had died in combat with the Nationalist forces in 1936, sufficient time seemed to have passed to understandably write his biography. Yet not everyone shared this understanding.

In his capacity as Vice-premier, Xi Zhongxun approved the writing of such a book. But someone or perhaps more than one in the inner circle of Communist Party power, for reasons not entirely clear, were most unhappy about it. Like hounds in the hunt, they smelled blood, and reported their concerns directly to Chairman Mao. Mao Zedong, already smarting from his disastrous Great Leap Forward campaign, was vulnerable and feared a conspiracy.

To this simple biography of his old and faithful comrade, Mao uttered one powerful sentence: “Using novels to be anti-Party is a new invention”.

Actually Mao never read the book. His pointed and poisoned sentence was based entirely on his presumption that somebody was against him behind his back. In Mao’s mind Xi Zhongxun could be that person. He had harbored this feeling since the late 1950s, and it became stronger and stronger with the knowledge that Xi had approved publication of this book seemingly praising someone else other than the great Mao without his knowledge or consent.

This cryptic remark about a book eerily preceded the publication of another influential Chinese book, the famous Little Red Book, more properly known as The Quotations of Mao Zedong in which 427 remarks, many as short as his condemnation of Liu Zhidan’s biography and those who arranged it, were to guide the dark forces of the impending Cultural Revolution that was waiting to unfold a few years later.

Mao’s sentence was like a thunderbolt that startled first the Party and then the whole country. Most of the Chinese Communist Party high position-holders were speechless. No one knew what to say or how unsafe it might be to say anything, and accordingly no one stood up to defend Xi Zhongxun. Was it true that the Chinese Vice-premier was anti-Party? Was an anti-revolutionary really in their midst?

Up to this point, Mao had done nothing but publicly praise Xi Zhongxun as a person “down-to earth, a living Marxist.” No Chinese could hope to get a more favorable appraisal than this, particularly from the great leader Mao himself. If Mao had said that Xi Zhongxun was a Marxist, then he must be a very good one, indeed. As far back as 1951 Mao had nominated Xi Zhongxun as the Director of the Party Propaganda Department, one of the key positions of the CCP. The Director of the Party Propaganda Department has the power to decide what to say and what not to say in the entire country. Yet suddenly such a living Marxist was not a Marxist any more. Was he a conspirator? It sounded weird and surreal. Or did Mao really believe that his close and long-standing colleague was anti-Party?

Perhaps he didn’t. Literally Mao said later that “Xi Zhongxun is a good comrade, how could he be a trouble?” Mao seemed to back-peddle, saying that he was not targeting the Liu biography specifically and that what he had said was just a general statement. Still the suspicion generated in Xi’s direction was allowed to foment. Why didn’t Mao release Xi Zhongxun from all suspicion? Mao never gave an answer up until his death in 1976.

The opportunists took full advantage of this ambiguous situation. Xi Zhongxun was put under suspension from all his official positions and duties despite Mao’s past high praise. He was just forty-nine years old and at the peak of his political career. But this one sentence from Mao was sufficient for him to be placed under house arrest and confined to the Central Party Academy in the west of Beijing. For his part, Xi Zhongxun could do nothing but wait for further resolution.

If patience is a virtue, then Xi Zhongxun was most certainly a virtuous man. He could go nowhere and had nothing to do. He spent the time reading and growing vegetables and corn. As the seasons passed, he made his harvest and gave half away. He was waiting, hoping maybe one day the situation would change and he would be allowed to work in Party politics again.

If this misfortune had happened to any other officer, they would rightly feel devastated, but not Xi Zhongxun. He was a true veteran of Party politics and had been there 27 years before. That was in 1935 when the revolution was still young and the outcome uncertain. Once the left-wing of the Party thought he was a traitor and decided to execute him in Yenan. It was Mao and his current Premier Zhou Enlai who rescued him then, believing the young man was a committed Communist. Coincidently, the same fate had been suffered by Liu Zhidan in that same year and it was Mao himself who likewise saved Liu from execution as well. Perhaps this had some effect on Mao’s thinking towards Xi Zhongxun and Liu Zhidan’s biography as he was certainly prone to paranoia that could be easily exploited by others. As for Xi Zhongxun, he was deeply indebted to Mao and Zhou Enlai for saving his life. He had no reason to start any conspiracy against either of them. He knew that, Zhou knew that, and when thinking straight, Mao knew that.

The trouble was that Xi Zhongxun definitely said too much. A man with a down-to-earth attitude always speaks too much for his own good. This was especially true concerning Mao’s catastrophic policies started in 1958 when the Great Leap Forward caused millions to die of starvation. This ambitious industrialization campaign designed to catch up with England and the U.S.A. sought to raise steel production to an unrealistic level. Each village built a small furnace. Since they had no iron ore to smelt, they collected any metal from households, including bowls and cooking pots. The peasants were fooled into believing that in the future they wouldn’t need any cooking pots since they all would eat in free canteens. How lovely! Unfortunately in the end, they didn’t produce any steel but lost all their basic cooking materials.

With this kind of nonsense taking place behind the grand slogans of the Great Leap Forward, Xi Zhongxun was one of a few honest persons who stood up and pointed it out. As Mao said he was down-to-earth and had the wisdom of common sense so prized by his mentor. He could not lie and Mao could not ignore it. Xi said what he thought and that marked his destiny.

But truth or lie, Mao never liked criticism from his colleagues, and his critics fell one after another and vanished from the political landscape. Often they vanished entirely. Xi Zhongxun actually was lucky. Other Chinese who fell out with Mao could face catastrophic consequences. Yes, he was under house arrest and excluded from his duties, but he still had his salary and his Party membership. He was far away from any life-threatening danger like he faced 27 years ago in Yenan. Perhaps that is why others didn’t come to his aid. After all, things could be much worse than being put on paid leave while the ‘investigation’ into any wrongdoing continued.

This sudden loss to the Xi family confused everyone. Little Dragon boy, Xi Jinping, was aware of the changes at home. His father didn’t go to Zhongnanhai anymore, the residence of the Central Government where Mao and other top leaders of China lived and worked. No one could explain what was going on. Xi Jinping was just 10 years old. He was not the eldest child of the family, but he was the eldest son. Actually he wasn’t the eldest son either, as he had an older stepbrother from his father’s previous marriage, but they lived separately.

Though Xi’s family was suffering, they still lived a privileged life. Xi Jinping and his siblings, two older sisters and one younger brother, were all enrolled in a school designated for the children of the privileged elite. The school Xi Jinping attended was hardly an ordinary school. It was the 1st August School that catered to the children of the most important officers and officials of the People’s Republic of China.

The school was established during the civil war time in Yenan. It had the duty to look after the children while their parents were fighting at the front. There was no smell of privileges at that time. Later with the victory of the Communists all over China such schools moved into the cities. To the memory of the triumph of the People’s Liberation Army, which was established on the 1st August 1927, the school Xi Jinping attended was named after it. Each year on the 1st of August the whole of China still celebrates ‘PLA Day’.

As Vice-premier, Xi Zhongxun belonged to a cadre of high officials whose children were all entitled to attend the 1st August School, together with the other children of all the top leaders of China. Their huge privilege was taken for granted as a matter of course.

During the civil war time such privileges could not be possible, but after the Communists won the war, more and more privileges became possible. It could even be pinned down exactly when it all started: in 1955. In that year an event took place which reshaped Chinese history. On the 8th of February 1955 a new ranking system imitating the Soviet Union was introduced into the Chinese army.

In its past the Chinese PLA had never had ranking. According to the orthodox Communist doctrine, soldiers and officers were both equal; as reflected in their uniforms, they were all theoretically the same. Before 1955 it was hard to tell who was high, who was low in the military. Now all this had to change. All military officers would get their ranking; marshals, generals, colonels were created and officers were assessed and assigned their rank by their individual merits.

Just as the army got their ranking, so did the civil servants, government ministers, department directors and so on. As Vice-premier, Xi Zhongxun’s salary was nearly as high as that of Mao, the Chairmen of the Communist Party. Set at 400 RMB monthly, this was more than 10 times the wages of Mr. Peng, the lowly local Party official in rural Juncheng who would one day become his Little Dragon’s future father-in-law.

Typically different ranking had different privileges, such as housing, service cars, and uniforms and so on. The children were young, but they picked up on the differences of the ranking very quickly. The impact of the parents’ ranking was to follow onto their children. The ranks of their parents made them not ordinary children any more. They were children of the ministers, generals and all kinds of highly ranked office-holders, and they knew it. In another word a new aristocracy was born, complete with heirs.

At the time, of course, nobody thought that they were creating a new aristocracy; they still call themselves the people’s servants but the fact is they were not. The intention sounds nice, but in practice it just makes the situation more confusing and eventually hypocritical. Copying the Soviet Union seemed to be the correct Communist thing to do for the young Chinese government.

Even though Xi Zhongxun lost his position, it didn’t mean his privileges had completely vanished. Yes, he was suspended, but his privileges were not ripped away, including the elitist education of his children. His friends and old comrades, a social network built during the years of war-time was still there as well. This network would play a large and instrumental part in his yet-to-be determined future. Without this network there would be no future story of either the father or son’s political career to be told.

Far away from Beijing that newly born Tiger baby girl did not share any of these privileges. Her father, Peng Longkun, the humble director of the local culture house eared a maximum monthly salary of just 40 RMB, hardly enough to raise his family without the small supplemental income earned by his singing wife.

The two families had nothing in common except one thing: both the families’ heads were Party members albeit at totally different ends of the ranking spectrum. Still, there was a tie of sorts, as fine and delicate as gossamer threads.