Читать книгу TOGETHER THEY HOLD UP THE SKY - Martin Macmillan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Family Reunion

ОглавлениеMillions of urban Chinese young people sent to the far-flung countryside were similarly wondering when they could go back to their parents. As months turned into years, the situation looked more and more hopeless. So their parents, the generals and high-ranking officials, started to act. They didn’t say Mao’s campaign was wrong or challenge it in any way publicly; instead they just quietly started bringing their children out of the countryside. As with any top-down nationwide bureaucratic policy, there were bound to be loopholes to be exploited. The best way to bring their sons and daughters out of their desperate placements with the peasants was to let them join the military. After all, to be a soldier was as patriotic as being a peasant in the ideology of the times.

Military positions were much coveted as a way to better the lives of many in China, and it was not as easy as walking into a recruitment office and signing up. But for this group of top echelon and well-connected parents, it was a much easier job. The generals used their power to recruit their own children and the children of their friends wherever and whenever they could. Mao’s generals knew how to look after each other’s children without bringing any negative attention to them.

To join the military ranks in China meant one didn’t need any food ration card or even any personal files; the military would look after everything, from clothing to pocket money while the local authorities had nothing to say. A whole new identity, in a way, could be constructed by joining the military, not entirely unlike the French Foreign Legion. And nearly all young people who had been sent off to the countryside were old enough to enlist. It was a perfect solution to this dilemma. The old yellow uniform became out of fashion and the new green military uniform replacing it quickly became the favorite outfit of young people lucky enough to wear one.

Seeing that other young people were now discretely joining the military with the help of their family connections, Xi Zhongxun’s wife didn’t stay idle. Her influence was not enough to bring Xi Jinping or his elder sister back from the Shaanxi or Inner Mongolia countryside via the military route, and her youngest son still with her in Henan was too young to enlist. But she was able to use her connections to get her younger son allocated to factory work in Beijing at the age of sixteen. After all, peasants, soldiers and workers were the three prongs of the revolution, and better to be a sweatshop laborer to avoid going to the countryside like his older siblings.

Mao seemed not to know what was going on with his campaign. He might have pretended he didn’t know. So far his wish to educate China’s urban youth in the countryside, the cradle of the revolution, turned out to only affect those who were unable to leave; mostly the children of the cities’ working classes. These hapless youth, who already knew the hardships of their factory-working parents, were going to stay in the countryside for seven or eight years and a few of them would stay there for ever.

The situation at the village where Xi Jinping stayed was becoming unbearable; all his mates from Beijing disappeared one after another, as Chinese would say, through the back door. No surprise there. Most of their parents had high military backgrounds. Xi Jinping was the only one left behind. It wouldn’t have been a good feeling, demoralizing to say the least, especially after his abortive attempt to leave on his own resulted in his returning to Liangjia River in Shaanxi province. Everyone else had managed to escape. Now he would truly have to survive among these strangers, his fellow Chinese countrymen.

Xi Jinping didn’t get someone to help him leave the countryside like his mates. There was no one in any position to do so. Being abandoned, we’d reckon, made him even stronger. Without these experiences he probably couldn’t have put himself on the ladder to the top position in the country. He might not have learned what Mao had envisioned, but he had learned a great deal about himself and his country.

We have to keep in mind that Xi Jinping’s mother, Qi Xin, was not just a housewife who happened to be well-married. Her own family roots were not those of an ordinary family either. Her father graduated from Peking University at the beginning of the century and went on to serve a number of different warlords in north China as well as taking on several local political positions. Compared to her husband, the former Vice-premier, she had an even more privileged background.

As a schoolgirl in Beijing, she followed her older sister to Yenan after the Japanese occupation. At that time she was just thirteen. At the age of fifteen she had already joined the Communist Party, quite a feat. Though she had not taken any important position she had been very active in the Party, and after 1949 she worked in the prestigious Communist Party’s Central Academy, where Mao himself used to be the Director. She had seen first-hand the war with Japan, the civil war with the Nationalists, and the building of the nation from the inside. She was a loyal and committed Party member in good standing. She didn’t have much to fear. No one could say anything against her, and she knew that.

In 1972 Qi Xin turned forty-four. She was determined to defend her family no matter what. She had to. Now her husband had been under arrest and she had not seen him for over six years. Her eldest son, Xi Jinping, worked on his own in Shaanxi Province, her daughter was still working on a military farm in Inner Mongolia. She had to abandon Beijing and move to Henan with her youngest daughter, while her younger son was doing hard labor in a factory. Her family didn’t look like the close-knit Chinese family it had been at all. She had nothing to lose.

As it happened, in 1972 Qi Xin’s mother, a female revolutionary veteran fell ill in Beijing. Qi Xin had found an opportunity. In order to see her ailing mother, she would need permission to travel to Beijing. She wrote a letter directly to the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, her husband’s former boss, asking for his permission to come back to Beijing. As the wife of the former Vice-premier she still had privileges to contact the top leadership. How her letter reached the Premier, however, is unknown, and again it might be through her revolutionary veteran sister who was safe and sound in Beijing. It was definitely not through the China postal service. If she had just posted the letter into any letter box, it would definitely end up at a police station and likely not be delivered. It must have been entrusted into the hand of a sympathetic go-between with direct access to Zhou Enlai himself.

Since Mao had never said that her husband was an enemy of the people directly, there was room for some hope. In fact, for both Qi Xin and Xi Zhongxun their Party membership was never revoked. Still it was a surprise and huge relief when word was received that permission was granted for her request. In addition to Qi Xin being allowed to travel to Beijing to see her sick mother, she could also arrange for all of her children to also come back to Beijing and gather at her sister’s home.

Emboldened by this success, Qi Xin did the unthinkable. She raised three more wishes to the Central Party.

She wanted to see her husband

She wanted a home in Beijing

Her husband’s salary should be paid, at least partly

How extraordinary that someone would dare to raise these conditions to the Central Government during the Cultural Revolution! Xi Jinping’s family, through the bravery and sheer tenacity of his mother, proved that they were still a force to be reckoned with.

Soon all her three wishes materialized. It was supposed that Zhou Enlai arranged everything personally. Xi’s family may thank Zhou Enlai as they certainly should, but their case was very special. Over the years of his persecution a number of high-profiled people put in nice words for Xi Zhongxun, but Mao ignored all of them, choosing to leave Xi Zhongxun in the dark, in limbo. Nobody could reason with Mao. All that could be done was just to accept what it was and wait for the chance to use something or someone in the system at an opportune moment. Such a plan had to be under Mao’s radar and had to be rationalized away as orthodoxy to anyone questioning it.

Before the year was out, the Xi family happily reunited in Beijing. All the family members were allowed to visit their father at an undisclosed location somewhere in Beijing where he had been incarcerated since 1966. Xi Jinping never mentioned that he was at this reunion with his father. But in his mother’s memoir she recorded the event. When her husband saw the children, he cried and said he could not recognize them anymore.

Xi Jinping was now a nineteen year-old young man. Years of harsh countryside life had changed him considerably; as had his other siblings’ experiences changed them. They had grown up quite a lot due to their circumstances, and not just the passage of time.

“Have you joined the Party?” This would have been the essential question Xi Jinping’s father would want to ask his eldest son. His father had joined the Communist Youth League at the young age of twelve, and then joined the Party at fourteen. His mother joined the Party at the age of fifteen. Their whole political careers were thanks to their Party membership. Whatever the circumstances Party membership was essential. That was the only passport to any success in China.

Xi Jinping’s answer to his father would have to be “No”. At age nineteen he was certainly old enough to join the Party but he hadn’t even joined the Communist Youth League, the preliminary organization leading to potential Communist Party membership. His father, the former Vice-premier of China must have been dumbfounded.

It certainly didn’t very look good for a young man who was trapped in the countryside not even applying for Party membership. Where was Xi Jinping’s future, if he didn’t join the Party? To achieve anything at that time the first thing to do was to be part of the political system. There was no way around it. In fact all descendants of the old veterans had applied for Communist Party membership, nearly one hundred per cent. Xi Jinping must have been totally naïve to not do anything about it. Obviously, he didn’t fully understand or accept that reality, at least not yet.

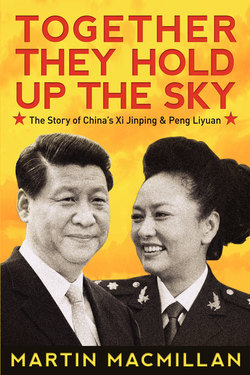

To document this miraculous family reunion, Qi Xin, along with her two daughters and two sons went to a photography studio to have a family photo made. Unfortunately her husband, Xi Zhongxun, was still under detention, and his absence in that family photo spoke volumes. But for his wife and children to all be together after so long and such a fierce struggle was truly amazing and needed to be recorded. The five of them looked delighted, happy, even glorious. Other than the silent absence of the head of the family, there was no sign of depression in this remarkable photo.

In the absence of her husband it was Qi Xin, their mother, holding the family together. What she had achieved in bringing them all together in Beijing, even temporarily, was just the start. With her husband in jail, she now had to play a big part in her children’s careers. She brought fresh hope to her family by her demonstration of personal courage, and she got results. From then on, throughout their lives, Qi Xin continued to provide valuable guidance, support and a strong role model for her children.

The trip to Beijing also reconnected the Xi family with the power center of China. This is a very important consideration as all political and social power was centered in the capital. It would be easy to forget oneself and be forgotten outside of Beijing in the countryside, and of course this was exactly Mao’s strategy. This family visit in the center of Beijing served as a wake-up call for Xi Jinping. After the family reunion, he started to change.

Xi Jinping returned to his small village in Shaanxi a changed young man. The news that he had seen his father sent a clear signal to the village. There was obviously something going on in Beijing. The peasants were eager to hear as much as they could from him upon his return.

Xi Jinping had even more shocking news for the local officials. Mao’s hand-picked successor, Lin Biao, had died in a plane crash in Outer Mongolia, then a Russian satellite country on the Chinese border with its semi-autonomous region of Inner Mongolia. What in the world was Lin Biao doing flying there? On the tragic night of the 13th of September 1971, Lin Biao took his wife and his only son, along with a small entourage of close supporters and family, and secretly boarded a British-made Trident passenger jet airliner, one of thirty-three ordered for the Chinese air force and the national civilian airline.

Nobody knew exact how they died. There was much exciting speculation in Beijing. Some said the Trident had been deliberately shot down by a Chinese missile. Some said they had lost their orientation and had flown out of China unknowingly. The official version was that Lin Biao was trying to defect to Russia and the aircraft had run out of fuel. The story sounded like a political thriller full of tension and mystery and intrigue.

What Xi Jinping reported to the locals was too shocking to believe. Why Lin Biao? Wasn’t he in second place, right after Mao, in the Party’s inner circle? Hadn’t Mao pursued and persuaded him to take on this position? Wasn’t Lin Biao present at every one of Mao’s public appearances, always making sure he got their ahead of Mao so he could be seen and photographed welcoming and greeting Mao? Why go to the Soviet Union? Wasn’t Russia still the enemy of China following their armed border confrontation in 1969? If this were true, how could Chairman Mao, their revered leader, have hand-picked such an evil person to lead China in his eventual absence?

Soon classified documents came from Beijing proving what Xi Jinping had said was correct. According to official Communist Party documents, Lin Biao was a traitor and had tried to flee China following a failed coup attempt against Mao Zedong. Lin, his wife Ye Qun who was also a powerful Politburo member, and their son, an Air Force officer had laid plans to assassinate Mao by blowing up his train. Unaware of the supposed plot against him, Mao nevertheless changed the travel route of his train, thus avoiding the attack, and made it back to Beijing unharmed. His bodyguards foiled several more attempts over the next twenty-four hours, and all evidence pointed to Lin.

Supposedly Lin Biao and his family thought they might have enough support in the military to flee to south China and engage Mao loyalists militarily with support from the Soviet Union. But when they heard that Zhou Enlai had discovered their intention and was investigating it, Lin Biao abandoned this plan and knew he now had to escape. His plane crashed, the official documents stated, because it ran out of fuel before it could reach the Soviet Union, killing all on board. Forensic tests conducted by the Russians at the crash site confirmed that Lin Biao and his family had died in the crash.

Further, Beijing decreed that Lin Biao’s photos should be taken down immediately and all references to him, written or spoken, should cease. Anything associated with Lin Biao became taboo and forbidden.

The Central Party’s document stated Lin Biao was driven by a morbid ambition for power and that he tried to assassinate Mao. Mao saw through his plan and so he cowardly ran away and died trying to reach China’s enemy, the Soviet Union. A very bizarre story! But at that time most people believed it. They didn’t dare to ask many probing questions such as Mao’s seeming lack of wisdom and insight in promoting such a person to the top of power in the first place. Such questions were never raised. Most people believed every word coming from Beijing, and these words were few and well chosen by the Party’s propaganda team. The local people in Liangjia River village must have had a thousand questions, many not voiced, for Xi Jinping. He certainly could not answer all of them, but as a person with special connections to the inner circle of power, the young Xi Jinping stood out much clearer; he was someone now, and his demeanor was different as well. But just who was he?

Having come back from Beijing, Xi Jinping started to change. The first thing he did was apply for membership in the local Communist Youth League. His application was rejected. Membership wasn’t automatic, even in this remote area of China. Supposedly the reason for his rejection was because of his father’s fallen status. But it could have been for a different reason related to Xi Jinping himself. Did the local people trust him?

Xi Jinping did not give up and applied for a second time. And a second time he was rejected again. Determined, he continued to try. As Xi Jinping has said later in his career, he then had a long conversation with one of the local Youth League members. This conversation began the build-up of a close relationship with this leader, and being impressed, he decided to help the young man. He told Xi Jinping that the trouble with his Youth League application was not just his father; it was also because his files sent from Beijing were very damaging.

Included in his files were details of Xi Jinping’s arrest by the Beijing police and spending some months in the youth re-education facility when he had tried to leave Liangjia River and illegally fled back to Beijing. What additional details may have been in his files are unknown. According to an interview given years later, Xi Jinping persuaded this man to destroy his files by burning them. His friend in the local Communist Youth League burned them for him. A piece of history went up in flames and stays mysterious till today.

Such was the persuasive ability of the young Xi Jinping. With the damning records gone and obvious high level local support, the local Communist Youth League decided to take him in at last. Xi Jinping was very proud of his action and the fact that he had persuasive powers over those supposedly above him, and he has told this story to the public without hesitation.

Having achieved the first step of Youth League membership, Xi Jinping was next chosen as “Activist of Educated Youth”. Loosely translated, the title “Activist” meant that he worked hard and talked loudly to others about what the Party newspapers were saying, primarily a lot of Marxist jargon.

Xi also worked hard as a laborer in his village alongside the peasants. At least he tried. He was assigned to work on the infrastructure of the commune’s fields, one of the hardest jobs in the countryside. The local peasants still remember that for a year he wasn’t able to carry two buckets on a yoke across his shoulders. He often slipped and fell going downhill, spilling out all the water or grain contents in his buckets to the chagrin and amusement of his co-workers.

But for what Xi Jinping lacked in physical skill he more than made up for in determination. He was determined to prove himself. As the village peasants recalled, in one year’s time he could carry a one hundred kilogram sack of grain while walking five kilometers at one go. In winter time he joined the peasants to build a canal. He was the first one to jump into the icy, muddy water to empty the canal.

He was trying to blend in with the peasants, but his privileges never left him and now followed him here. The corn flour he got was pure flour, while the peasants got flour with bran. He now lived independently. He had his books and read often till late into the night using an oil lamp in his cave. He read and re-read Marx, Lenin, Mao’ works and some scientific school books he had brought with him from Beijing. The books made him very different from the illiterate villagers around him. And he was very protective of his precious books. The locals recalled that Xi Jinping could become very angry if anyone dared to touch his books.

Xi Jinping knew by instinct how to please the local people. He entertained them with his story-telling prowess, though what he said to them, we don’t know. According to his own claims, the local people liked him and respected him. He was regarded as an able young man. The local officials would even consult with him if they had some conundrum to sort out. Indeed he had a lot to offer, coming from Beijing with his very high-level family background. His family once hosted all of the leading political and societal celebrities of Beijing, a world apart from the one he now inhabited in rural Shaanxi, but the social skills he observed from his parents, he could now practice and apply for himself with the peasants of Shaanxi.

Another ingratiating thing Xi Jinping did was to read the Party newspapers to the local peasants. Reading newspapers during the Cultural Revolution wasn’t just a casual pastime; it was a big thing since every newspaper was an official document of the Party and therefore regarded as ‘gospel’. As most of the peasants couldn’t read, direct access to Party newspapers through Xi Jinping was a big deal to them and elevated their life and status. This must have been personally fulfilling to Xi Jinping as well, even though he had to relay negative propaganda about his own father and other family friends. Imagine the irony of his situation.

Sometime after he was elected as an “Activist of Educated Youth” in the local Communist Youth League, Xi Jinping was sent to join the campaign for so-called “Guideline-Studies”. This was the official campaign put in place by the Central Government after the suspicious death of Lin Biao to discredit him publicly as a traitor and discourage any further conspiracies against Mao.

In a document sent out to the whole of China, Mao raised just three issues. He wanted his people to:

Study Marxism

Be united

Don’t be involved in conspiracies

That was all. The Great Leader didn’t demand that much, just three things. Even though the proclamation was rolled out across the country, it really didn’t speak to the vast majority of rural peasants or city workers. Mao knew very well that Chinese peasants or factory workers could not conduct any conspiracy against him. Obviously the people Mao wanted to reach were his generals. For him, if the military leaders just promised these three things, he would be happy with them. Although never admitting it, Mao’s sense the despair in his so-called national proclamation can be heard in the subtext.

The new Guideline-Studies campaign consisted of reading the documents from Beijing and holding local discussion sessions. Since Xi Jinping came from the inner circles of Beijing, it was surmized by the local officials that he had much more inside information than any of them had, and they elevated his status accordingly. He could see the times had changed. Just a few years ago, he had come to the countryside as a naïve young boy; now he was sitting together with the local Party members and officials planning an important campaign. This was the first time he was somebody above the ordinary peasants. He didn’t need to work in the fields. Now his work was sitting somewhere and just talking in his refined Beijing Mandarin accent. Not bad for a young man with no title, no Party membership, no local connections; just a young man from Beijing who had a prominent father brought down from power by a scandalous campaign.