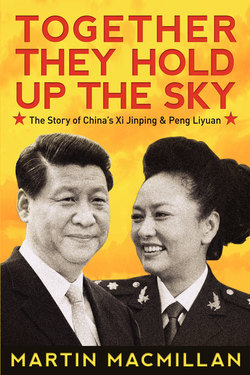

Читать книгу TOGETHER THEY HOLD UP THE SKY - Martin Macmillan - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Aftertaste

ОглавлениеOf course, the short-sightedness of Mao’s free travel scheme eventually played itself out. It wasn’t free at all and cost the government of China a great deal. Soon or later it had to be stopped. As the winter of 1966 approached, the enthusiasm of the people ebbed as well and situations worsened for many. Xi Jinping and his young friends had to face this new reality that was temporarily masked by the excitement of exotic travel in the south of China.

Back in Beijing the situation was becoming worse for many families. Some of the veterans were evicted from their homes and relocated to much smaller quarters. Some families lost their accommodations altogether and were forced to move elsewhere, far from Beijing, as punishment. Xi’s family lost their home and his father’s salary was stopped completely. The family had already been moved temporarily to a small accommodation available to Qi Xin, Xi Jinping’s mother, who worked at the Central Party Academy.

Even as an employee of the Academy and a Communist Party member, Qi Xin didn’t hold any significant power to fend off the constant attacks. She was the wife of Xi Zhongxun and attracted the attention of the Red Guards. Her crime was that she didn’t draw a clear line between herself and her husband who had been branded a counter-revolutionary. So she was also critisized in public. All over the Academy were hanging posters written in black ink naming her as a traitor. She was paraded through the campus of the Academy in the typical humiliating style of the Red Guards, and the parade eventually became physical attacks as well.

The biggest part of the tragedy for Qi Xin was that her children had to witness it. The two youngest children didn’t fully understand what was going on, but her eldest daughter, Qi Qiaoqiao, was already twenty and read all those accusatory posters. She was shocked and challenged her mother:

“Mom, did you say some rubbish? You mustn’t be a traitor! Now it is different times. Although the masses are critisizing you, it still is down to whether you don’t say what you shouldn’t say, don’t be a traitor, adhere to the principles.”

As family members of Xi Zhongxun they had to suffer so much. One can easily imagine how terrible it must have been for Xi Zhongxun himself.

While the young teenage Xi Jinping was travelling with his mates in south China, terrible things were happening to his father. His father was being forced to attend numerous public gatherings orchestrated for self-criticized and public humiliation or even to be beaten. Such public self-criticism sessions for veteran cadres were common throughout China at that time. Such ‘struggle sessions’ were developed in the Soviet Union as early as the 1920s as a way to purge political opponents under the rubric of the ‘class struggle’. Mao effectively used this device of manipulating the mob, as have many others throughout history.

The former but now disgraced Vice-premier, Xi Zhongxun now found himself on the top of the ‘Capitalist Roadster’ list, the term invented to denounce those who had betrayed socialism, meaning Mao. Xi Zhongxun’s name was still in the memory of many people, but the Red Guards made sure that memory was not a good one. The Red Guards didn’t forget that Mao had said: “Using novels to fight the Party is a new invention”, his indirect but pointed criticism of Xi Zhongxun for having authorized the publication of The Biography of Liu Zhidan.

Xi Zhongxun was brought to the city of Xian where he used to be head of the province. In the ancient city of Xian where the Terracotta Warriors were later to be unearthed, Xi had to endure more public assaults. The northwest people of the area seemed to be every bit as brutal as their soldier ancestors, the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China.

Nowadays there is a picture of Xi Zhongxun on the Internet showing him standing on the back of a truck being driven through the crowds. Hanging on the front of his chest is a sign with his name. He was tortured by the Red Guards quite badly in Xian. This time he was close to death. Clearly the rather civilized house arrest of Xi Zhongxun since 1962 was being replaced with public brutality in the service of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Purge was now being enhanced with persecution.

Among the veteran cadres, the country’s President Liu Shaoqi, having been named the top enemy of the people and the socialist cause suffered the most. He became so ill from the constant public verbal and physical assaults that he didn’t recover and soon died anonymously in 1969. His death was not even told to the family for some time afterwards.

Similarly in 1967 Xi Zhongxun was tortured nearly to death. The news somehow reached his old colleague, Premier Zhou Enlai. Having sympathy for him and still with some power in his grasp, Zhou Enlai ordered an airplane to be dispatched to bring Xi Zhongxun back to Beijing for medical treatment. Xi was temporary put in jail, ostensibly as protective custody for his personal safety. This temporary arrest turned out to last for the next eight years.

But in this way, Premier Zhou Enlai saved Xi Zhongxun’s life. His heart was still on the side of the old veterans. Mao knew that. That was why he never trusted his Premier. He rather relied on his wife, the infamous Jiang Qing, than his loyal Premier. Today many Chinese would like to assert that Mao actually disliked his wife and protected Zhou which is just an empty wish of millions of Chinese to rewrite the memory of this brutal time with gentler brush strokes. Whatever good Zhou Enlai was able to do for the country as a whole, and unfortunate loyal citizens like Xi Zhongxun, he likely did on his own without any explicit or implicit aid from Mao.

The last academic semester of 1966 ended for most school children like a gigantic display of Chinese fireworks, with explosive, noisy, colorful and demonic glitters. Over a year’s break had now gone by in total chaos. All the schools and universities had been closed down. Not all students had the luxury of a travel holiday, and left largely to their own devices or manipulated by factions of the Red Guard, hooliganism was rampant. Something had to be done. Students had to return to study. So Mao said: “Continue Revolution by going back to schools.” But there was no going back to school. The education system was in shambles. The chaos on the street now moved into the classroom.

In her village, little Peng Liyuan was old enough to go to school. But even far from Beijing in rural areas, school was not the same as before. There was no joy in young children going off to school as before. On the contrary, school had become very uncomfortable. Not much real learning was going on.

Class started for Peng Liyuan at 8 A.M. The first thing students did in assembly was to sing The East is Red, a song to praise Mao.

“The east is red,

The sun is rising.

In China emerged Mao Zedong.

He serves the people for happiness

And he is a big saviour of the people.”

Day in and day out, Peng Liyuan and her fellow students had to sing the same song of praise. To worship is not a strange thing for any nation. But how they worship varies and always turns out to be very peculiar from an outsider’s view.

To worship Mao during the Cultural Revolution through songs of praise has its odd side. We have to point out that the Chinese had no historical or cultural tradition of singing together in unison of prayer. The Buddhists don’t gather and sing. Using a choir and making it a routine ritual for everyday life was absolutely new to the Chinese people. Oddly enough, this taken-for-granted communal behavior found everywhere in the Christian individualist world had no parallel practice in collectivist Communist China. It must have seemed strange indeed to now be singing songs of praise together regularly and religiously.

After the morning song, instead of studying science or literacy the first class turned out to be reading Mao’s works, specifically his famous Little Red Book, fully titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong. The book easily fits into the palm of one hand with 274 pages of cryptic political doctrine. It’s hard to think that young school children like Peng Liyuan could understand these quotes, but as millions of other Chinese children had to do, she had to know them by heart and study them with the utmost seriousness. Alongside Lenin and Engels, this was only the third official publication on Marxism allowed in the entire country for three years. Demand was so enormous that hundreds of new printing houses had to be hurriedly built just to keep up with it.

In fact Peng Liyuan and her schoolmates needn’t go to the school to learn Mao’s words. Now in every corner, in every family’s home, Mao’s Little Red Book could be seen. On the radio, in newspapers, on any wall along street, in buses, in shops and restaurants, even on stamps, in every possible place there was no way of avoiding Mao’s phrases. Very soon nearly everyone could remember every page of that Little Red Book as the goal had been set for 99% of the entire Chinese population to read it.

To study Mao’s words was not a task the school children were allowed to mess about with. But how could the young children sit for hours upon hours and listen to this tedious political teaching? Imagine young school children having to memorize and endlessly discuss the following quote from Mao?

”Revisionism, or Right opportunism, is a bourgeois trend of thought that is even more dangerous than dogmatism. The revisionists, the Right opportunists, pay lip service to Marxism; they too attack ‘dogmatism’. However, what they are really attacking is the quintessence of Marxism. They oppose or distort materialism and dialectics, oppose or try to weaken the people’s democratic dictatorship and the leading role of the Communist Party, and oppose or try to weaken socialist transformation and socialist construction. After the basic victory of the socialist revolution in our country, there are still a number of people who vainly hope to restore the capitalist system and fight the working class on every front, including the ideological one. Moreover, their right-hand men in this struggle are the revisionists.”

Soon the students lost their patience. All schools lost a sense of discipline; the classroom became as chaotic as a Chinese tea-house. Boys and girls walked in and out of classrooms freely; the teachers had no power to control them and they were constantly afraid of being physically threatened or attacked by the more rowdy students.

Very little academics were occurring in the schools at all. Peng Liyuan’s math studies were a disaster. Her math teacher just wished she could make as much efforts for math as for singing, for in all this chaos, Peng Liyuan had found her refuge in the most important part of the Communist Party propaganda machine – singing. For where pseudo-academic study of Mao’s Little Red Book wouldn’t reach, the lighter touch of song and dance certainly would.

Singing turned out to be the most important part of the Party’s propaganda war chest. School children might not pay attention to the teaching of math, and rural peasants might care less about the slogans plastered all over buses and walls, but certainly everyone would turn out for a live propaganda performance. Each school developed a propaganda team during that time. Talent like that displayed by the young Peng Liyuan was much needed. The teams performed songs and dances for any political events being held in the area. They didn’t call themselves performers; instead they said they were “fighters”. After all, according to Mao’s wisdom in his Little Red Book,

“A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”

Typical propaganda shows usually started with an announcement to reinforce the revolutionary focus. A charismatic student would excitedly proclaim: “Mao Zedong’s thought! The art propaganda team starts to fight!’” Then the troupe would take to the stage and start singing songs and performing dances with titles like Red Guards Seeing Chairman Mao, Yanbian People Love Chairman Mao, Soldiers Missing Chairman Mao and so on. The cult of Maoism was definitely being hammered home but cloaked in colorful costumes and sweetly sung by cute schoolchildren. Not only that, it was literally the only show in town so sure to garner large and appreciative audiences.

For Peng Liyuan, this was the only type of performance art available to develop and display her considerable though youthful talent. Her clear and strong voice and natural ways in front of an audience were very much needed by her school’s propaganda team. And in a time without any other entertainment throughout China, her singing could bring some small joy to the people.

There was a dance called Four Old Men Studying Mao’s Work. On the stage four actors dressed like old man, each carrying Mao’s Little Red Book while dancing and singing. This performance tried to show people that everyone should study Mao’s work. The message was “You’re never too old to learn Maoism.” The four old men were usually played by young girls, just the opposite of traditional Chinese theater where sexism often meant that young men portrayed women as women were not allowed on the stage. This was very entertaining for ordinary people and quite brilliant for the troupe to turn the serious political propaganda into a novelty. At the same time it was subtly displaying the Communist agenda of promoting the new role of revolutionary women in public. As Mao was to famously proclaim in 1968, “Women hold up half of the sky”.

Just as there were no math and sciences, there was no decent arts education available to students in China at that time either. A decent music education didn’t exist for Peng Liyuan. All she could do was learn to sing the propaganda songs. There was no chance of learning to read sheet music, and learning to play a musical instrument was out of the question. Her natural talent for singing pulled her through. Peng Liyuan also had one other advantage in her favor. Besides her naturally good singing voice, she had spent a lot of time as a youngster following her mother around the countryside to see her performances. This intimate familiarity with her mother’s performing undoubtedly gave the young Peng Liyuan a degree of confidence in front of an audience, and soon she was also tapped to present the school’s propaganda shows as well as sing in them.

The shows Peng Liyuan’s mother performed in were also heavily censored directly by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qin. Jiang Qin had the absolute power to decide what the entire Chinese public could and could not see and hear in all the performing arts. One word from her could kill a drama, a song or even an actor’s career that she happened not to like.

Officially available to the Chinese public, generally speaking, were just eight dramas; two of them were ballets, the rest were Beijing Operas. Under Jiang Qin’s censorship, the whole country was confined to seeing just these shows for an entire decade. Repeated again and again and again, every word of those eight performances were eventually memorized by almost the entire Chinese population.

Prior to the Cultural Revolution, ‘Cultural Houses’ had been set up by the government throughout China with a main aim of promoting the Party’s agendas via the arts. Peng Liyuan’s father had been running the local Cultural House. But during the unofficial purging that occurred during the Red Guard years, many of the Cultural Houses were temporarily shut down and dismantled. They often were reorganized into new propaganda teams after some time of chaos. Their revised purpose was now simply to replicate locally the eight revolutionary dramas promoted by Mao’s wife.

But what were Jiang Qin’s own proclivities in entertainment? Would she spend all her time watching her own limited revolutionary creations, over and over? The answer is, “Certainly not!”

While millions of Chinese were forced to watch her handful of morally correct revolutionary dramas year in and year out, Jiang Qin spent a lot of her personal time privately watching western movies like Million Dollar Mermaid (The One Piece Bathing Suit), a 1952 American biopic about an Australian swimming star who created a scandal when her bathing suit was considered to be indecent, The Red Shoes, a 1948 British drama of a young ballet dancer torn between the man she loves and her dream of becoming a prima ballerina, the British action film Deadlier Than the Male, a 1967 James Bond take-off, and the highly innovative 1959 French film Hiroshima, Mon Amore (24 Hour Affair). She adored Greta Garbo so much that she is rumored to have said that she would like to give her an Oscar. Jiang Qin’s excuse for this perk of watching these risqué foreign films was that she could learn skills from the west in order to defeat them.

The great Mao, however, had totally different tastes from his wife in entertainment. He didn’t watch any foreign movies and preferred traditional Chinese operas, all of which were banned by his wife. Secretly, well-known actors would be summoned to perform privately for him. This double life was not just restricted to Mao and Jiang and the top echelons; it was reflected throughout Chinese society in the ordinary people’s attitude and behavior as well. On the top of students’ desks was Mao’s Little Red Book, but underneath the naughty boys were reading Chinese ‘pornographic’ novels such as The Heart of a Young Girl, meticulously copied by hand and spread from student to student under the tables.