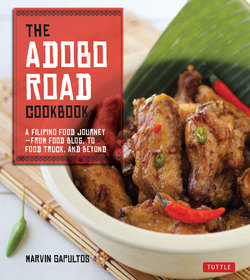

Читать книгу The Adobo Road Cookbook - Marvin Gapultos - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFROM BLOGGER, TO FOOD TRUCKER, TO AUTHOR: MY FILIPINO FOOD JOURNEY

My earliest memories of Filipino food aren’t the kind that I fondly recall. It's true that like most Filipino-American kids, I enjoyed eating lumpia, pancit and garlic-fried rice—the trifecta of crowd-pleasing Filipino food. But my fondness for Filipino food stopped with spring rolls, noodles, and rice. When it came to the dishes my mother loved to cook and my father loved to eat, soulful dishes like pinakbet, adobo, or sinigang, I protested at the dinner table like any reasonable child would—I cried. Loudly.

No, I wanted to eat pizza, and burritos, and hamburgers, and fish sticks (oh, how I loved fish sticks!). I wanted what my friends at school were eating. I wanted the food I saw on television. At the time, as far as I could tell, Magic Johnson drank 7UP, not calamansi juice. Punky Brewster shared a plate of pasta with her dog, Brandon, not a plate of pancit. And I was certain that Hulk Hogan’s mantra of training, saying your prayers, and eating your vitamins had nothing to do with the fermented shrimp paste that my mother claimed would make me a strong boy.

My mother made sure my two brothers and I were fed, even if it meant learning completely new Western dishes to satisfy her young ones’ palates. Ever accommodating, she also made sure to cook a separate Filipino dish for her and my father to eat. Otherwise, my dad would have protested like any reasonable grown man would—he surely would have cried. Loudly. Like father, like son, I suppose.

Mind you, these dual dinners didn’t last forever. As we got older, my brothers and I gradually began to appreciate Filipino food. However, I didn’t fully realize how much I loved my mom’s Filipino cooking until I moved away to college. In college, I began to miss the smells of steamed rice and piquant adobo—the smells of home that I once ignored and took for granted. Soon enough, the doldrums of dorm food made me see the error of my ways; I had no choice but to eat pizza, and burritos, and hamburgers, and fish sticks (oh, how I detested fish sticks!). So weekend trips back home became more than just a chance to do my laundry for free—those weekends became savored opportunities to eat as much of my mother’s cooking as possible.

Despite the rude culinary awakening I experienced in college, it took a few more years, and another change in my life, to trigger a deep, hands-on interest in Filipino food. The trigger? Marriage.

The woman I married isn’t a terrible cook. In fact, my wife is a great cook. But it just so happens that my wife isn’t Filipino. No matter how delicious a chicken piccata my wife could make, it wasn’t chicken adobo ! So whenever I had a sudden urge for some home-cooked Filipino food, we either had to drive a couple of hours to my parents’ for dinner, or my cravings simply went unsatisfied.

It wasn’t long before I figured out that it would be more convenient to learn how to cook Filipino food on my own, rather than trekking out to my parents’ house every week for dinner—besides, my dad might have started charging us for groceries.

So never having cooked a Filipino dish in my entire life, let alone even assisting in the preparation of such a dish (I rarely helped my mom in the kitchen as a kid—I watched cartoons), I set out to learn about the food of my culture. My crash course in Filipino food started with basic questions over the phone to my mother, my grandmother, and my grandmother’s sisters (“The Aunties”): “What kind of meat do you use in lumpia?”, “How long does it take to cook pinakbet?”, “Will bagoong (fermented shrimp paste) kill me?”

When phone calls weren’t enough, I found myself in the kitchens of my mom, my grandmother, and my aunties, learning alongside the women of my family who, combined, have hundreds of years of experience honing and perfecting our clan’s specific recipes. After much encouragement, I learned to be patient in the kitchen, to trust my instincts and my taste buds, and that no matter how utterly funky a jar of bagoong smelled, its contents were indeed safe to eat.

Now armed with the secrets and sage advice of my family, I began cooking and experimenting with Filipino ingredients—to varying degrees of success, of course. And to document my new culinary trials and tribulations, I started the food blog Burnt Lumpia (at the time, I was such a novice Filipino cook that I always burned at least one spring roll when making a batch, hence the blog name). What initially began as a means for me to record my recipes, Burnt Lumpia inexplicably became an entertaining distraction for other Internet foodies as more and more people began reading my blog on a regular basis. I like to think these readers were laughing with me, rather than at me, as I posted stories of my trial-by-fire in Filipino cookery.

As I posted different Filipino recipes on my blog each week, I was ecstatic to find that my readership included not only Filipinos, but readers of different tastes and ethnicities as well. Ultimately, I wanted to urge everyone interested in Filipino food to ask the same questions I did of my family. I wanted people to discover their own family’s food traditions and cultures, in the kitchen and at the table, Filipino or otherwise, and celebrate these customs to keep them alive. But I wanted to do more. Eventually, I wanted everybody to experience Filipino flavors and ingredients.

But in order to bring a greater awareness and appreciation of Filipino cuisine to the rest of the world, I realized I needed to go beyond blogging. So with my blog recipes in hand, I opened my own Filipino restaurant—well, sort of.

In June of 2010, I opened The Manila Machine—Southern California’s very first gourmet Filipino food truck. However, The Manila Machine was much more than just a converted taco truck serving Filipino food. It was my own mobile restaurant serving my take on Filipino cuisine. In every sense of the word, the Manila Machine was my personal vehicle for bringing Filipino food to the masses.

Among The Manila Machine’s tasty offerings was chicken adobo, pork belly and pineapple adobo, spicy sisig, and lumpia. Also made to order were a number of pan de sal sliders—bitesized sandwiches served on traditional Filipino rolls. Not only was I able to successfully field test many of my own recipes, but thousands of Angelenos were also getting their first taste of Filipino food from my mobile kitchen. And they were coming back for more! Soon, people all over Southern California were buzzing about Filipino food, and I was the one feeding them—from a truck no less!

At the same time, however, Burnt Lumpia and The Manila Machine both made me realize that there are so many other Filipinos who, like myself, fear losing their own family recipes and simply want to learn more about their own cuisine and culture. I also now know that people of all ethnicities want to enjoy and experience Filipino flavors as much as they do Thai, Vietnamese, and other Asian cuisines.

TRADITIONAL WAYS ARE WONDERFUL; BUT NEW WAYS, WHEN APPLIED WITH UNDERSTANDING AND SENSITIVITY, CAN CREATE A DISH ANEW—WITHOUT BETRAYING THE TRADITION.

—DOREEN G. FERNANDEZ, FOOD WRITER AND HISTORIAN

This shared curiosity in Filipino cuisine, and the need to preserve Filipino culture, is the inspiration for the cookbook you now hold in your hands. This isn’t the end-all-be-all Filipino cookbook—far from it. My hope is that this book serves as a starting point that will spark a new and lasting interest in Filipino food and culture.

The Manila Machine was Southern California's first gourmet Filipino food truck.

Hungry customers line up for Marvin's take on Filipino cuisine.

I want Filipino-American parents to start feeding their toddlers bitter melon so that we can have a new generation of Pinoys craving pinakbet.

I want college kids to have a freezer bag full of frozen lumpia, made by their own hands, so that they can have a mess of crisp spring rolls whenever they please for those late night studying (or drinking) sessions.

I want newlyweds to learn that they must always keep their stash of rice full and at the ready so that they can avoid having to order a pizza when the in-laws pay a surprise visit.

I want Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike to gain a basic understanding of Filipino cuisine so that it can be enjoyed and embraced rather than avoided.

And I want my own children to grow up loving the dishes I cook for them—Filipino food and otherwise.

And that should be a simple enough goal for all of us.

THE NEXT BIG THING?

Today, Filipino food seems to stand at a culinary crossroads. In a world of Twitter, Facebook and food blogs, food-minded people are constantly looking for the next big culinary trend. A hot-button topic within some of these food circles is whether or not Filipino food can be this so-called “next big thing.” Alas, the same questions always arise:

“Why isn’t Filipino food more popular? Why isn’t Filipino food more mainstream?”

Filipino food can be more than simply “trendy”—it is an incredibly diverse and complex cuisine with a multitude of indigenous variations and global influences.

Whether or not Filipino food goes “mainstream” isn’t really a concern of mine. For me, in order for Filipino food to be appreciated a little bit more, it must first be understood a little bit more.

With such a diverse culinary heritage and an abundance of nuanced flavors, it’s only a matter of time before the rest of the world comes to appreciate and understand Filipino food.

UNDERSTANDING FILIPINO FOOD

The Philippine Archipelago consists of some 7,000 islands clustered in the warm Pacific waters of Southeast Asia. Across these islands, over 100 distinct languages are spoken amongst a multitude of regional ethnicities. And with native cooking techniques such as adobo (braising food in vinegar), kinilaw (quickly bathing raw food in vinegar or citrus juices), and ginataan (cooking food in coconut milk), it is easy to assume that the cuisine of the Philippines consists of an indigenous panoply of Malay-based dishes. But this assumption is only partly true.

Adobo, pancit, lumpia, and shrimp—just a small sampling from a typical meal at my grandmother’s home in Delano, CA.

Harvested rice from my uncle’s farm in Badoc, Ilocos Norte, Philippines.

A backyard barbecue in progress at my parents’ home in Valencia, CA.

There is much more to the story of Filipino cuisine. With a long history as a trading partner with the Chinese, Arabs, Indians, Portuguese and Japanese, the already diverse Malay menu of the Philippines is further accented with flavors and cooking techniques from other parts of the world.

While culinary influences from India, Portugal, and Japan are understated, in certain Filipino dishes, the Muslim influence from Arab trading partners is very apparent in the Muslim region of Mindanao in the southern Philippines.

CHINESE INFLUENCE

Although the Chinese began trading in the Philippines as early as the ninth or tenth centuries, they did not begin to settle in the Philippines in earnest until the sixteenth century. The Chinese influence on Filipino cuisine is most apparent in our pancit noodles and lumpia spring rolls, but Chinese ingredients such as soy sauce, black beans, tofu, pork and pork lard—just to name a few—have all become mainstays in Filipino cooking.

SPANISH INFLUENCE

The Spanish first arrived in the Philippines in 1521, but would not control the islands until 1565. The Philippines would remain under Spanish rule until 1898. During this 333-year reign, the Spanish would leave an indelible mark on Filipino culture and cuisine.

The Spanish colonists, homesick and hungry, soon began introducing Spanish ingredients, cooking techniques, and dishes to the Philippine natives. Before long, Filipinos began using the Spanish sofrito of tomatoes, onions, and garlic cooked in oil as a base to their own dishes, while also embracing and adapting Spanish dishes such as caldereta, empanada s, embutido and flan, among many others. And because Spanish ingredients were well beyond the means of many Filipinos at the time, Spanish dishes were reserved for special occasions. Even today, Filipino dishes of Spanish origin are usually only served at birthday parties, graduation parties, and the occasional Manny Pacquiao fight party.

MEXICAN INFLUENCE

Mexico and the Philippines may seem like strange dinner companions, but because both nations were under Spanish rule at the same time, their connection becomes clearer. In fact, during much of its time as a Spanish colony, the Philippines were actually governed indirectly via the Spanish viceroyalty in Mexico City—and this was long before the time of conference calls and telecommuting.

Between the years of 1565–1815, Spain transported goods between its two colonies via the Manila-Acapulco Galleons. These huge ships traveled across the Pacific from Manila to Acapulco only once or twice a year, thereby introducing innumerable Mexican influences into Filipino cuisine. The galleons brought New World crops to the Philippines, such as chocolate, corn, potatoes, tomatoes, pineapples, bell peppers, jicama, chayote, avocado, peanuts, and annatto—all of which you will find in one form or another in this cookbook. And because the galleons traveled in both directions, the Mexicans received rice, sugarcane, tamarind, coconuts, and mangoes from Philippine soil.

AMERICAN INFLUENCE

Following the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Spain signed the Philippines over to the United States as part of the Treaty of Paris. The Philippines would then spend the next half-century as a colony of yet another country and living with a new military force in their presence.

The U.S. military legacy in the Philippines, culinarily speaking, left behind a new fondness for all things American, including things like hot dogs, hamburgers, fried chicken, and ice cream. Even processed convenience foods such as Spam, corned beef, evaporated milk, and instant coffee became highly prized pantry items for the Filipino.

FAMILIAL INFLUENCE

Above all else, Filipino food is largely shaped by individual family traditions and customs. The same dish made in one household will greatly differ from that of the household next door. Taking things a step further, the same dish prepared by one family member will greatly differ from that made by another family member.

This is no more evident than with my own grandmother and her sisters. Even under the same roof and in the same kitchen, each sister prepares her own very distinct version of adobo. It is this diversity that makes Filipino cuisine so wonderful.

Speaking of my grandmother and her sisters…

GRANDMA AND “THE AUNTIES,” OR MY THREE GRANDMAS

Much of what I know about Filipino food, I learned through a lifetime of visits to the home of my grandparents; Juan and Estrella Gapultos (AKA “Grandpa Johnny” and “Grandma Esther”). Two of my grandmother’s sisters, Carolina (AKA “Auntie Carling”) and Flora (AKA “Auntie Puyong”), also live in the same household with my grandparents. And although Carling and Puyong are technically my great aunts, I’ve grown up calling them “Grandma” as well (sorry for all the aliases—Filipino families are “Wu-Tang” like that).

While Grandma Esther does have other siblings, Grandmas Carling and Puyong have lived with my Grandma Esther for my entire life. They are the triumvirate of culinary tutelage with which I was raised—each grandma having her own speciality and excelling at different culinary arts.

My Grandma Esther is definitely the executive chef of her kitchen, directing her (older) sisters in their tasks and orchestrating the many multi-course meals that have fed our family over the decades. With a degree in Home Economics from the University of the Philippines, my Grandma Esther is an all-around great cook, though her specialty is in desserts. As such, in addition to my grandmother being an expert in traditional Filipino sweets, she’s also adept at baking everything from multi-tiered wedding cakes decorated with ornate sugar flowers, to mini pecan tartlets.

Grandma Esther and me.

This grandma clan ain’t nothin’ to mess with. From left to right: Grandma Puyong, Grandma Esther, and Grandma Carling.

Grandmas Carling and Puyong, on the other hand, both specialize in the old school: traditional Filipino fare from the Northern Ilocos region of the Philippines. Most every Filipino comfort food from my childhood has been prepared by either Grandma Carling or Grandma Puyong. I imagine if there were ever any sort of “Filipino Throwdown” or “Iron Chef Philippines” competition, those two young ladies would wipe the floor with whoever crossed them.

And although my three grandmas sometimes bicker amongst themselves in the kitchen (as all sisters do), they always manage to create beautiful, soulful meals together.

In fact, if I could choose my last meal on earth, it would consist of delicacies described in this book: my Grandma Carling’s Pancit Miki (page 58), my Grandma Puyong’s Pinakbet (page 48), and my Grandma Esther’s Buchi (page 130).

EAT LIKE A FILIPINO

Although this cookbook is broken down into convenient sections that focus on different Filipino “courses,” it should be noted that, typically, Filipinos do not eat meals that progress from small plates, to main courses, to dessert. Instead, all courses are brought to the table and presented at the same time—desserts included.

Now this doesn’t mean that we’ll have a bite of cake sandwiched between nibbles of spring roll, slurps of soup, and mouthfuls of roast pork (though, admittedly, I’ve done that once or twice at family parties, but I digress), but rather, it signifies the importance of food to a Filipino family. Feeding, being fed, and sharing in a meal is vital to all cultures—but especially so with Filipinos.

If you’ve ever eaten a Filipino meal with a Filipino family, you probably know that one of the most difficult things is trying to get up from the dinner table—not only because you are full of food, but also because the host is likely to insist that you keep eating some more! And even if you do manage to escape the dinner table, chances are that you will be bringing more food home with you in doggie bags. Filipino food: the gift that keeps on giving.

AN ABUNDANCE OF RICE

Central to any Filipino meal is the appearance of rice at the table. Rice is served with all meals throughout the day. For breakfast, fried rice (Fast and Simple Garlic Fried Rice page—53) is often served alongside eggs and sausage, or a warm champorado (Chocolate and Coffee Rice Pudding, page 135) can also be had for breakfast. Steamed white rice, of course, is ubiquitous for lunch and dinner and serves as an absorber of soups and stews, or as a bed for protein and vegetables, or as a blank canvas for various dips, sauces and condiments. Rice even appears in many Filipino desserts, either in its sticky glutinous form for heavy sweet snacks, or when milled into rice flour to form the foundation of many cakes and dumplings.

A TRADITION OF SOURNESS

As you’ll find throughout the recipes in this book, the most dominant flavor in Filipino food is sourness. This sourness can be a quick zing provided from anything like a dipping sauce made of fresh calamansi lime juice, or it can be a more restrained and refined sourness that can be found in adobo s slowly simmered in vinegar and spices (page 68).

The Filipino penchant for lip-puckering zest is not without reason. In the tropical climes of the Philippines, the preservative powers of vinegar were a culinary necessity for centuries, long before refrigeration was available.

Also arising from this tropical climate was an abundance of fruit and vegetables ripe with tang. Aside from the citrus bite of calamansi, sourness was also sought out in green mangoes, tamarind, guavas, and a variety of other exotic produce.

As such, throughout the ages the collective taste of Filipinos has centered around sourness.

But to think that all Filipino food is sour would be a great underestimation. Filipino cuisine is rich in all flavors of the palate.

SAVOR EVERYTHING, WASTE NOTHING

While “nose-to-tail” eating may be somewhat of a hot trend in high-end restaurants these days, Filipinos (along with many other cultures) have long appreciated the virtues of eating whole-hog.

There are a variety of wonderfully delicious Filipino dishes in which organ meats and other “scrap” bits are used and highlighted. The Filipino use of offal is one of cultural tradition that occurred before, during, and after colonial times and still continues today. This tradition of enjoying every last bit of an animal arises not only out of thrift or necessity, but because these bits taste darn good.

Throughout this cookbook, I do provide a small sampling of such recipes to perhaps whet your beak with “real-deal” delicacies ranging from chicken feet and livers, to salmon heads, to various tasty bits of pork. These tasty bits will open a whole new delicious world of flavors and textures.

Savor them. Enjoy them.

ABOUT THE RECIPES

You’ll notice that with many of the English recipe titles throughout this book, I also provide a Filipino translation. I realize that with over 120 languages (and several hundred dialects), there is more than one way to refer to a dish. As a general rule, I tried to stick with the more common Tagalog dialect for easier identification among my Filipino readers. But there are a few instances in which I use the Ilocano terminology for a dish. In these cases, the specific dish may be one from my childhood that I learned from my grandmother, aunties, and mother.

As I mentioned earlier, my culinary viewpoint largely stems from my American upbringing in an Ilocano family originating from the Northern Philippines. With that said, I also have a unique culinary disposition from years of developing recipes for a blog read by an international audience, as well as developing recipes for a successful Filipino food truck whose customer base was the multi-ethnic hodgepodge of Los Angeles, California.

As such, the recipes I provide in this book are easy-to-follow, tried-and-true recipes that can serve as a basic guide to the pleasures of Filipino cuisine, authentic dishes that can easily be enjoyed by Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike.

But in addition to some classic and traditional recipes, I’ve also (ahem) taken some liberties with my own “new school” interpretations. These new adaptations are not meant to dilute Filipino tastes. Rather, they are creative steps in the continuing evolution of a vital cuisine, taking advantage of traditional flavors and ingredients to spark a new interest in Filipino food and culture.

Mabuhay !

Marvin Gapultos

www.BurntLumpiaBlog.com