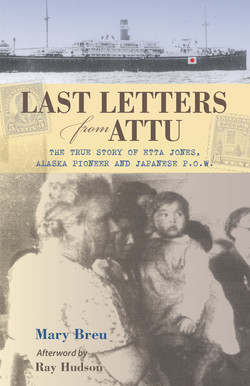

Читать книгу Last Letters from Attu - Mary Breu - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Tanana

1922–1923

It was early in the afternoon on August 20, 1922, when Etta and Marie first glimpsed their future home. The village of Tanana was situated on flats at the junction of the mighty Yukon and Tanana Rivers. Small covered fishing boats and a sternwheeler were tied to the dirt riverbank. Front Street ran along this riverbank and Second Street was parallel, one block back. These two treeless unpaved streets were dusty in dry weather and muddy when it rained.

Tanana waterfront, on Yukon River, 1922.

IT WAS NOT A VERY IMPRESSIVE sight but one that even then radiated charm. Most of the houses were of log, looking small and dingy from the outside, but how cozy and warm and hospitable on the inside, we later found out. Standing stark in the sunshine, without the benefit of shade trees, the cabins were revealed by the clear sky, which was a deep blue usually associated with a summer day.

On Front Street were the stores or trading outfits, two hotels, a pool hall, and a small church. At the extreme end of these buildings was Fort Gibbon. The fort had been abandoned, but there were still a few clearing-up personnel. As soon as they were finished with their assignment, they, too, would move away and the buildings would be left with a caretaker.

When our boat was tied to the bank, all passengers went their own way, and we realized that if we wanted our baggage moved, it was up to us to do it ourselves. It was apparent that we must find a house to live in because we could not afford hotel rates. The hotelkeeper’s wife was friendly and helpful. “You’re the new teacher? Well, I’m on the school board. We have been expecting you, and I can help you with a place to live.” Her husband had a choice log cabin that he would rent us for $15 a month. We were enchanted with our new home, known as the Scotty Kay House, one of the few in town that had a second story. It had three rooms downstairs and two above.

Marie and unidentified child in front of Etta and Marie’s home, Tanana, 1922.

To me, that first night in our new home was enchantment itself. I hung out the bedroom window, listening to the silence, which was so great it beat insistently on the ears. It was a living stillness. The soft velvety darkness spoke a friendly welcome, and in the distance a hoot owl added his voice. He must have been some distance away, but the clear, vibrant air brought him very near. To me, he was a friendly fellow, but not to Marie. She covered up her head, saying, “Shut the window. The silence hurts my ears.” She never got used to that silence, which increased when the snow came. As poet Robert Service says, “Full of hush to the brim.” There was a brooding, tangible something in that silence that sometimes seemed friendly, sometimes frightening.

The front windows of Etta and Marie’s house faced another two-story cabin across the dirt road, the home of a recently married former Episcopalian missionary.

WITH FAULTLESS MANNERS, this friendly neighbor soon called on us, inviting us to dinner. The other guest at the dinner was an old friend of her husband’s, one Charles Foster Jones.

Foster was born on May 1, 1879, in St. Paris, Ohio, to Caleb and Sarah Jones. Foster had two siblings, Mamie, 7, and Xerxes, 4. When Foster was four months old, his mother died of typhoid fever. In 1880, Dr. Jones married Julia Goodin, and they had six children: Cecil, Oasis, Caleb, Tracy, Anita, and Lowell. Foster’s father was a physician and founder of Willowbark, a residential facility in St. Paris for recovering alcoholics. He owned a drug store, was involved in numerous activities in the United Methodist Church, and traveled around the state giving speeches encouraging his listeners to improve their health and lifestyles. With all of his commitments, Dr. Jones had little time for day-to-day interaction with his nine children, but he had exceptionally high standards and there was no doubt in their minds what he expected of them.

In 1897, before Foster finished high school, he had had enough of his stern father and small-town life, so he struck out for Washington state. When he arrived, word was spreading that gold had been discovered in Alaska, and Foster contracted a serious case of “gold fever.” He asked his father to loan him $600 so he could out-fit himself to become part of the gold rush, and Dr. Jones complied. This loan was deducted from Foster’s share of the estate when his father died in 1924.

Charles Foster Jones, Tanana, circa 1920s.

Beginning in 1898, Foster’s occupations were mining and prospecting in various sections of Alaska. He never struck it rich, nor did he go broke. Images of big, strapping, bearded, gruff men are conjured up when one thinks of mining prospectors. Foster was none of these. He stood five feet seven inches tall, weighed 150 pounds and was complacent and easygoing. Through the years, Foster corresponded with his family, but he never returned to his birthplace.

Foster met Michigan native Frank Lundin in 1911 and they became friends and were mining partners for the next several years. At one point, they were buying supplies to take to their cabin. Frank purchased the necessary staples, but Foster bought a book of poems by Robert Service. Frank commented that if they ran out of food, they couldn’t eat the book, but Foster said, “When we get back to our shack on Birch Creek, look at the pleasure we will get from reading those poems.”

By 1922, they had established residency in Tanana and were involved in civic and social activities in the community. Frank wrote, “In 1922, I was elected to the [Tanana] School Board. We had no teacher, so I had to arrange for one. I wrote to the Commissioner at Juneau, and he wrote back saying that he had already arranged to have a teacher sent to Tanana. The teacher who applied for the job was Marie Schureman, and when she came to Tanana, she had her sister, Etta, with her.”

BESIDES GOOD FOOD, we greedily ate up all the fascinating details of Foster Jones and Frank Lundin’s early experiences in Alaska. Both had joined the Klondike stampede going over the Chilkoot Pass in 1898 and had also been in the Nome, Fairbanks, and Ruby gold rushes. They related exciting times and many thrilling experiences as though they were commonplace occurrences. This same Foster Jones became very helpful in preparing us for the coming winter, the intensity of which we could not imagine. Many times that winter, when locked in by ice, snow, and cold, we blessed his thoughtful kindness.

There were offers of help from everyone in town. One brought us a gasoline stove, another cut our wood for the heater, and others fixed storm windows and doors. We were given advice, good advice, that we did not always follow, much to our sorrow later. It was necessary to get the work done quickly because freezing nights and snow flurries began sometime in September. Old-timers assured us that sixty below for a month at a stretch was not uncommon. Watch the bottle of painkiller, they cautioned, because it froze at seventy-two below. Marie gasped when she found in the school register a notation by a former teacher that school had been closed that day because the thermometer registered seventy-two below. It couldn’t get that cold. Or, could it?

Marie taught at the government school for white children who lived in and around Tanana. The schoolhouse was about two blocks from their home, and as she walked along Front Street she could hear the river as it cascaded over the rocks and she felt droplets of moisture on her face as the wind blew. She passed one-story log houses that were built close to the road and close to each other. Green plants and bright curtains made the small-paned house windows look festive. In summer, the yards would be full of flowers. Her walk took her past “Tower House,” the town’s hotel, which had a tower on it, hence the name. There were gaps in the old board sidewalk, so Marie had to be careful with her footing. The schoolbuilding was a one-room, low-roofed log cabin, heated with a wood stove.

IN OCTOBER THE LITTLE CREEKS and streams began to pour small pieces of ice into the river, gradually filling it with slushy ice. Then larger pieces appeared, the current slowed up, sometimes stopping for a few hours, then moving on again. The final stoppage came early in November, and it was a topic of general interest because the river could not be crossed while ice was still running. Perhaps a friend would telephone, saying “Ice has stopped,” and someone would be sure to mark it down. Mail delivery stopped until the ice was strong enough to be crossed.

Tanana Public School, 1920s. PHOTO BY J.O. SHERLOCK. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, ALASKA.

Next door to the school was the Arctic Brotherhood Hall, which was the meeting place for all community gatherings. It had a hardwood maple floor that was kept polished by the soft moose-hide moccasins that everyone wore. All winter, leather shoes were not worn because it was too cold. Feet froze in leather. Tales were told of “cheechakos” who refused to listen to advice about footwear and who suffered amputation of feet as a result of ski trips in fifty-below weather wearing leather shoes. It was in the Arctic Brotherhood Hall where dances were held which everybody attended. The slightest occasion made the excuse for a dance—some strangers in town, a holiday, or just plain Saturday night. Everybody danced. We had rollicking times. I remember one dance when Foster had been out on a trip, and his friends thought he would not be back for the dance. Yet, he was there, and danced as much as anyone, but in an unguarded moment, he admitted he had almost not made it. He had snowshoed twenty-eight miles that day just so he could make it. He did not consider that unusual, snowshoeing twenty-eight miles and then dancing half the night.

This hall was also the scene of many soul-satisfying Christmas celebrations in which everyone participated. The schoolteacher practiced with the children to provide entertainment. Committees were appointed to collect money and donations from stores and others. Another committee bought presents for everyone. Young men brought in a huge spruce tree, and women worked together to decorate it with trimmings belonging to the community. Those decorations were carefully put away from year to year. Gifts exchanged by the whole town were usually put under the community tree. There was a Santa, sometimes with his reindeer. No one was forgotten. Miners, woodcutters, and trappers came in for the celebrations. It was a happy, happy time. We were amazed that first year at the extent of this giving, and overwhelmed by what we received. Nowhere have I seen a truer demonstration of the Christmas spirit. After the entertainment and distribution of gifts, a dance, and such a dance!

Drinking water was obtained in winter from the river. Ice was as thick as eighteen inches. Some people stacked cakes of this ice on platforms in their yards, bringing a cake into the house as needed, allowing it to melt in the drinking water tank. “Stacking drinking water in the yard” was a standing joke.

As the days grew shorter, artificial light was needed later in the morning and sooner at night until on the shortest day, December 22, when the sun barely made a showing above the horizon, first peeping out at about eleven and disappearing again at one. We looked forward to Saint Patrick’s Day, because on that day, a six o’clock dinner could be eaten without a lamp. In midwinter, school children trooped by the house in the dark on their way to school, and often they could be seen finding their way home by moonlight, or, if there was no moon, with flashlights.

Early that first spring, we went on a hunting and trapping trip to Fish Lake, about twenty-five miles from Tanana, leaving while there was still snow to travel by dogsled, and the lakes were still frozen. It took two days, stopping one night at a roadhouse about ten miles from Tanana. At the Fish Lake Roadhouse, we found that the owner was away because he was sick, but everything was open, so in we walked and took possession. We sent word by the first traveler that we were there. The lake was full of muskrats, and as the ice gradually melted and disappeared, while Foster hunted “rats,” I wandered over the countryside, gathering the early flowers. It was a lonesome place. The few magazines it boasted were years old and well read. The old-fashioned phonograph fascinated us. It used old cylindrical records. I remember there were some made by Ada Jones, as far back as that.

Yukon River ice breakup, Tanana, with big ice chunks piling up on the shore, 1923.

The breaking up of the ice on the Tanana River was the big event of the year for all persons living along its banks. Many, in all parts of the territory, participated in the Nenana Ice Classic. They bet on the exact date, hour, and minute the ice would break up in Nenana, paying a dollar for each bet. There were over $100,000 in this pool, one person occasionally winning it all, but more often it was divided among several. “Breakup” came most often in May when the days were long. We sometimes wandered along the bank of the Yukon most of the night, which was daylight at this time of year, watching for this spectacular sight. It was worth watching, the ice buckling and being thrown many feet into the air. Noise from the grinding, huge cakes of ice was deafening, and the danger of flood from the damming of these cakes was very real and kept everyone on tenterhooks until the water was running smoothly. We stood on the bank and watched this huge pageant pass by. We saw caribou marooned on the floating cakes, perhaps too exhausted to try for the shore. Discarded articles from villages and towns hundreds of miles upriver went sailing jauntily by. All houses and yards were cleaned of refuse and put on the ice to be taken out.

After the ice was entirely gone, we loaded camping gear, food, and ourselves into a long poling boat and prepared to leave the village and drift on the Yukon River. In rowing through choppy water, an oar was lost, and there was no extra. It put severe strain on the ingenuity of the man of the party to keep that overloaded boat upright. With the use of a paddle, I tried to steer. Finally, with a sigh of relief, we entered the comparative quiet of a small stream that led to the river. We camped in the woods and slept under the sky. I can see and hear yet the swishing and bending of the tall birches as they thrashed in the wind high above us. The next day, the boat was reloaded, a makeshift oar was put into use, and we started again on the turbulent Yukon River with its dangerous submerged sandbars. The wind increased, bringing rain. It became necessary to camp again on a sandbar. By this time, the wind was roaring, too strong to put up a tent. The boat was turned on its side, and we crouched behind it as best we could. We could not build a fire, and what food we had was filled with sand. In fact, we were almost buried in sand. Then, to add to our miseries, the rain began. Finally, late in the day, the wind abated enough to allow us to make the return trip, and we arrived home in a drenching downpour, fur clothing soaked. The keenest memory that remains with me of that homecoming is the steady drip, drip of rain from the roof as it poured into the rain barrel at the door.

Foster (left) pushes a poling boat into the Tanana River with the help of an unidentified person, 1923.

Etta and Marie lived in a territory that was the size of 425 Rhode Islands, with wide-open spaces as far as the eye could see. A hundred thousand glaciers, some larger than entire states, had sculpted mountains, carved out valleys, and continued to flow and shape the landscape. Mountain ranges were higher, more rugged, and larger than any combined ranges in the Lower 48. Majestic Mount McKinley, the highest peak in North America at 23,320 feet, was in their back yard. Three thousand rivers, many gray in color because of glacial silt, rolled for hundreds of miles, passing through a vast wilderness. The river shoreline was punctuated by isolated villages, accessible only by boat or plane. In summer, wildflowers covered the endless valleys. Sightings of bald eagles, grizzly bears, moose, caribou, and wolves were commonplace. They had experienced temperatures that were so extreme they couldn’t be registered, had taken dogsled rides and boat trips. Their meals consisted of moose, salmon, and blueberries that were the size of strawberries. Just when it couldn’t get any more exciting, Foster made an announcement that would change two lives forever.

While Etta was working at the post office, Foster and his friend, Frank Lundin, walked in. Foster looked at his friend, nodded in Etta’s direction, and said, “I’m going to marry that girl.”

Tanana Post Office, where Etta worked in 1922.