Читать книгу Last Letters from Attu - Mary Breu - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Etta Jones was my favorite great-aunt. For my first twenty years and her last twenty, I knew her as a compassionate, generous, genteel woman. She was short in stature, and had pure white hair and jet-black eyebrows. I always knew she had an interesting past because bits and pieces were mentioned over the years. Relatives had kept all of Etta’s letters, photos, documents, and artifacts, and this private treasure was eventually handed down to me. In 2002, thirty-seven years after her death and at the end of my teaching career, I decided to put her story together to share with family members. While going through Etta’s extraordinary collection, I realized that her story deserved a much wider audience, so I began to write this book.

To start, I wanted to confirm that events she wrote about in her letters were accurate in her telling, so I checked details on the Internet. Everything I read that addressed her story contradicted what Etta had written and what I knew about her. And the more research I did, the more discrepancies accumulated. I decided that I needed to do in-depth research on documents and texts located in archives in Alaska, so in 2003, I obtained a grant from the Alaska Humanities Forum to travel there. After that, I made four more trips at my own expense.

My search took me to the National Archives, the Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, the Loussac Library, and the University of Alaska, all in Anchorage. I uncovered more material at the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks. I pored over Congressional records, Bureau of Indian Affairs records, archival documents, newspapers, and Australian and American texts. I interviewed and corresponded with key people who were involved, directly or indirectly, with Etta’s story.

Etta was a prolific letter writer. Her engaging writing places the reader alongside Etta and her gold-prospector husband, Foster, when they lived, worked, and taught in remote Native communities—Athabascan, Yup’ik, Alutiiq, and Aleut—in Alaska in the 1920s,’30s, and’40s. Etta’s and Foster’s backgrounds were as diverse as the landscape of the Northland, but they were both conscientious and diligent workers. Hardship became part of their chosen way of life, and they embraced it. Their goal was not to change Native cultures; rather, as conveyed in her letters and other documents, it was to teach their students reading, math, and some domestic skills.

Etta’s language vernacular differed somewhat from today’s usage; for example, she used the word “Japs” because it was a commonly used term in the United States during World War II. I have edited her letters for clarity and relevance. Her letter writing depended on the random delivery of mail in remote Alaska villages, so sometimes she added postscripts after she had signed off and was waiting for the mail to arrive. Or, when the mailman arrived unexpectedly, she would hastily compose brief letters to be mailed immediately.

Etta also wrote a fascinating sixty-four-page manuscript in 1945 that was never published. It is full of facts and impressions that give the reader special insights into life in territorial Alaska. I have included excerpts from Etta’s manuscript throughout this book’s narrative. Likewise, in 1967, Foster’s prospecting partner and friend Frank Lundin wrote an unpublished manuscript, in which he described their experiences during Alaska’s gold rushes in the early 1900s. Excerpts from Lundin’s manuscript are also woven into the narrative.

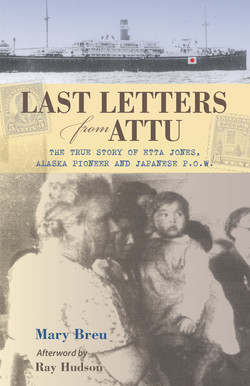

The photos in the book are primarily from Etta’s collection. For the captions, I’ve used the information Etta wrote on the back of the photos. If there was no inscription, I gathered information from her letters and unpublished manuscript. Regarding the photos of Attu,I’ve used several of Etta’s pictures of the Aleut Natives to document these disappearing people.

I have created a Web site to accompany this book, where the reader may find further material on Etta’s story, and a schedule of author appearances and book signings: www.lastlettersfromattu.com.

This book portrays events as they happened to Etta and Foster Jones. Qualities we often hear about, such as resolve and courage, are qualities that defined Etta Schureman Jones. She was a pioneer in Alaska Native villages. She was a remarkable woman who survived profound adversity. She played a significant role in a pivotal but less-known event in America’s history.

Etta Schureman, age 4, Ellen (Nan) Schureman (Etta’s sister, and the author’s maternal grandmother), age 6, Vineland, New Jersey, 1883.