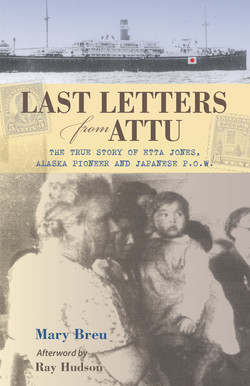

Читать книгу Last Letters from Attu - Mary Breu - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Tanana, Tatitlek, and Old Harbor

1928–1932

After Vitus Bering led a Russian expedition to Alaska in 1741, the vast populations of sea otter, seal, and fox in the Aleutian Islands region were perceived as commodities that were available for the taking. As competing companies strove to dominate the fur business, Alaska’s indigenous islanders, the Aleuts, were exploited because of their legendary hunting abilities. Forced labor, massacres, captivity, disease, and starvation diminished the Aleutian Islands Native population by half.

Grigory Shelikov established a Russian settlement at Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island in 1784. Ten years later, a school was built, and Russian Orthodox missionaries arrived and began teaching Native children reading and writing in Russian. Local languages were also recognized, and eventually alphabets for these were developed. Literacy in Russian and the Native language became goals of the schools. Recognizing that the Natives had thrived under difficult circumstances for a very long time, the priests were pragmatic in their approach. Instead of attempting to abolish the Native culture, they lived their Christian lives by setting an example—simple, humble living while practicing their religious doctrine.

A monopoly in the Alaska fur trade was created when the Russian American Company was established in 1799. Schools continued under the company, and promising students were sometimes sent to Russia for further training. The sea otter, seal, and fox populations were not limitless, and the company imposed conservation measures. Nevertheless, the fur trade declined. Hunting expeditions could last from two to four years, and the cost was prohibitive. With decreasing monetary returns, Russia started to lose interest in Alaska. The Crimean War and other external pressures added to the concerns of the government. American whalers and fur dealers had started to make their presence felt in the territory, and on March 30, 1867, Russia sold Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million. Russia continued to subsidize church schools for Native children until 1917. With the outbreak of the Russian Revolution, all funding for Alaska missions was terminated.

The Nelson Act of 1905 established a segregated system in which schools for Native children would remain under the control of the Department of the Interior. The goals for Native schools were twofold: integrate Natives into the white culture, and preserve the Native culture. Students in these schools were taught the most rudimentary reading and math, but the emphasis was on domestic skills for girls and woodworking and mechanical trades for boys. The Native children were provided with an unsuitable patchwork of American textbooks.

Having observed this educational disparity, in 1928, Etta decided to change the focus of her teaching. On her application for appointment in the Alaska Indian Service, she was very specific. “I wish to be more actively associated with the Natives.” Her wish came true when her application was accepted and she was assigned to teach twenty-four Athabaskan students in Tanana.

Foster gained employment with the Alaska Indian Service in 1930. He listed his experience as, “Clerked in a drug store and studied under a pharmacist and physician” [his father]. His skills were listed as “drawing, carpentry, operating gas and steam engines, cooking, and washing clothes.” He also stated that he was qualified to teach “arithmetic, history, geography, hygiene, and first aid.”

Transfers within the Alaska Indian Service happened frequently for several reasons: the teachers requested a transfer; the teachers met the needs of a different Native village; new schools were built and teachers were hired; unsatisfactory performance by a teacher required a replacement; or, when teachers left the Alaska Indian Service, the vacated positions needed to be filled. In the 1930s, in addition to teaching certification, employees of the Alaska Indian Service were required to successfully pass a Civil Service examination. Those who didn’t qualify were dismissed, creating open teaching positions.

When transfers occurred, expenses for the move were subsidized in one of two ways. If the Alaska Indian Service made the recommendation, it was deemed “not for the convenience of the employee,” and the Alaska Indian Service covered the cost of the move. If an employee requested a transfer, the employee had to pay his or her own expenses.

In 1930, Foster was assigned to Kaltag, an Inupiat Eskimo village located 327 miles west of Fairbanks, while Etta was transferred to Tatitlek, twenty-one miles south of Valdez and 450 miles southeast of Kaltag. In a letter dated June 19, 1930, the Commissioner of Education stated, “This transfer is not for the convenience of the employee.” There was no post office in Kaltag until three years later, so correspondence between Etta and Foster during that year was infrequent at best.

Tatitlek is an Alutiiq Indian village

on Prince William Sound in Southcentral Alaska. In 1930 it had a Native population of sixty-two; Etta was the only white person in the village. Describing her new location, Etta wrote, “Tatitlek is a small fishing village between Valdez and Cordova, twenty-eight miles from Valdez, fifty-five miles from Cordova. The ground is wet and swampy at all times. No wells can be driven. The water supply comes from a spring on the hillside. The Natives do a little trapping in the winter, but their main occupation is fishing for the canneries of Prince William Sound. They are industrious and thrifty, and make a fairly good living. The village is gradually growing smaller as families move to Valdez or Cordova.” The length of the school year was 159 school days, enrollment was twenty-two students, and the average daily attendance was eleven.

In 1937, villager Paul Vlassof wrote about his community: “Tatitlek is a little village located halfway between Valdez and Cordova. I think it is the nicest little place in Prince William Sound.

A view toward the Alutiiq village of Tatitlek, on Prince William Sound, from McDonald’s Island, 1930.

Tatitlek School, 1930. HISTORICAL ALBUM OF (BUREAU OF EDUCATION, BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS) SCHOOLS IN ALASKA, 1924–1931, VOL. 2 NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION PACIFIC ALASKA REGION, ANCHORAGE, ALASKA, RECORD GROUP 75, BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS BOX #234, FOLDER 05/04/08(2).

My home is halfway surrounded by trees, while out in front is the water and an island about a mile and a half long. There are about sixteen houses and about eighty-five people living there. My people make their living by hunting, fishing, and trapping. In the winter, we have dances every Friday and Saturday, and quite often we have our school programs. In the summer, it gets so warm that most of the people do their cooking outside their houses. The government schoolteacher governs the village with some help from a person from the village. There are no electric lights here, so we use gas lamps for light. Most of the houses have radios, which we listen to to pass the time in the evenings. So whenever you get to Tatitlek, drop in to one of the houses and see what kind of entertainment you get.”

In spite of the fact that Etta was in Tatitlek without her husband at her side, she had a successful year. In her Teacher’s Efficiency Record, her “success as a village worker” and her “ability to overcome difficulties” were rated “very good.” This report was issued on her eighth wedding anniversary.

At the end of the school year, Etta was transferred to Old Harbor on Kodiak Island.

On June 11, 1931, a radiogram was sent from the Office of Indian Affairs in Juneau to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.: “Request transfer George S. Wilson present salary from Old Harbor to Kaltag with transportation effective entrance on duty and transfer of C. Foster Jones from Kaltag to Old Harbor same salary with transportation effective entrance on duty. Also transfer of Mrs. Etta E. Jones from Tatitlek to Old Harbor transportation effective September first at salary of $1,620 per annum less $240 for school term. These transfers requested in order to place two teachers at Old Harbor as scheduled, retaining only one at Kaltag. As Wilson is unaccompanied, we can place him at Kaltag making it possible to place Mr. and Mrs. Jones together at a two-teacher school.”

A letter to Etta soon followed.

June 17, 1931

United States Department of the Interior

Office of the Secretary

Washington

Mrs. Etta E. Jones of Alaska

Madam:

You have been appointed by the Secretary of the Interior, upon the recommendation of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, an Assistant Teacher, Grade 6d-g, in the Alaska School Service of the Indian Service, at a salary of $1,620 per annum less $240 per annum for quarters, fuel, and light, effective on the date of entrance on duty, but not earlier than September 1, 1931, by transfer from Teacher, Grade 7d-g, at $1,800 per annum less $240 per annum for quarters, fuel, and light. New position. Employment and payment limited to the period of the school year. You are still subject to the provisions of the Retirement Act.

The Secretary has also approved the allowance of traveling expenses in accordance with existing orders and regulations, from Tatitlek, Alaska, to Old Harbor, Alaska. This transfer is not for the convenience of the employee.

Respectfully,

J. Atwood Maulding

Chief, Division of Appointments, Mails and Files

Through the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Order No. 2472

Etta and Foster were reunited after a year’s separation and would be together for the next eleven years. Before going to Old Harbor on Kodiak Island, Etta and Foster spent time with friends in Tanana, Fairbanks, Anchorage, and Seward. From Seward, Etta wrote to her mother and her sister, Marie, to share news of their reunion and express hopes for a long, happy life together.

Seward, Alaska

July 20, 1931

Dear Mother and Dump:

Well, here we are at Seward. It is a dull, rainy Sunday and I seem to have no ideas at all. We came in on the train from Anchorage Friday evening, and our boat does not leave until Tuesday night or Wednesday morning. But time goes quickly. There are many little affairs of business to be attended to.

Seward is much like Valdez in its setting, with high snow-capped mountains all around. The little town is on an apparently land-locked bay. The rain seems quite natural. It doesn’t seem to inconvenience very much, like Juneau. One doesn’t get very wet in it. This cool moist climate is a relief after the dry, hot, dusty Interior. Tanana was very hot before I left, and we almost suffered from the heat in Fairbanks and Anchorage. Nellie Grandison took us for rides in her car in Fairbanks, and in Anchorage friends took us over all the automobile roads of which the town boasts, about thirty miles. We both like Anchorage. It wouldn’t surprise me to find myself living there sometime. Foster liked the town well enough to patronize the bank, which surprised me. He opened an account there, and bought U.S. Steel through them.

Most of our fellow travelers on the Yukon River steamer came with us as far as Seward, and there we parted. The Los Angeles school marm and her sister from Nome stopped off at McKinley Park for a week. They had intended to stop only overnight and join us again at Anchorage, but the fascination of the park was too much for them (at $15 per day each for living in a tent).

It takes about three days to go from here to Kodiak, and there we shall probably have to take a small boat to get to Old Harbor. As you say, Mother, I am seeing something of Alaska. I missed a good chance to see more of it. I have always wanted to go over the Richardson Highway by automobile from Fairbanks to Valdez, but as the stage fare is $100 and I couldn’t connect with any private cars going over, I had given up the idea. The night before we left Fairbanks, I learned that Jack Coats was in town, husband of Dump’s friend in Chitina. I had just received a letter from Mrs. Coats, forwarded from Valdez, in which she said she had made arrangements for her husband to drive me from Valdez to Chitina if I would only visit her for a week or two. So in Fairbanks, when I learned he was there, my plan was suddenly made to go with him to Chitina, from there to Cordova over the Copper River Railroad, the most beautiful of them all, and join Foster again either in Seward or Kodiak. It would have cost much less, and there would have been over 300 miles of superb scenic highway. Of course, that was not considering his plans, but, drat the man, I could not locate him anywhere. Nellie helped me look for him. We found his car and his hotel and his friends, but we could not find him, and our train left at eight the next morning. So the Richardson Highway, Chitina, and the Copper River Railroad I still have to look forward to.

We bought an Underwood portable typewriter in Anchorage, so from now on you will not have to strain your eyesight trying to read my scrawl. I may get time to write in Kodiak or on the boat. They tell us we get mail only once a month in Old Harbor, but I think it may be as it was in Tatitlek, which was whenever a small boat goes to the town of Kodiak. There is also a government radio station at Kodiak town.

Love to all,

Tetts

Dump: From Anchorage I mailed you Mary Lee Davis’s latest book on Alaska. Hope you enjoy it as much as I have. Are you still wanting a silver fox? I saw some good ones today and can get you one if you wish.

ONE SUMMER DAY, we landed late in the afternoon at Old Harbor. As the Starr dropped anchor in the cool clear depths of the strait, we seemed to be in Paradise. The green hills were deep and smooth and luscious. From a distance it appeared like a well-kept lawn. “Wouldn’t think that foliage is shoulder high, would you?” said a fellow traveler. Later, we discovered that to be true. The silence after the noisy engine was soothing, and the shadows of the hills crept out over the smooth water. We landed at the rickety dock, with its unfinished dock house and barnacle-covered pilings. Although it was midsummer, it was fairly cool. The town was situated along the water’s edge, on a low bank, so low that at high tide sometimes it seemed as if the town would be flooded. The storekeeper welcomed us. He was practically the only one in the town. All the Natives were working at the salmon cannery at Shearwater Bay, about twenty-five miles distant. Their little toy wooden houses and tiny yards were neat and clean. The hills across the strait, within sight of the village, were snow covered most of the year. On part of another island there was a glacier that glistened all the year round.

While in Pittsburgh, Etta had embraced the tenets of Christian Science. She believed that God and creation are good and that spiritual thought would bring a person closer to God. She also believed that healing was possible through the power of prayer, and she prayed on a regular basis. Her doctrines allowed her to accept other religious sects that she encountered, including the Moravians and Alaska Natives’ Russian orthodoxy.

THE ALUTIIQ NATIVES of Kodiak were friendly and likable. Being very devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church, they steadfastly refused to drink during Lent. I loved to go to special services in their church, be it Easter or Christmas. They had good singing voices and good ears for music. In the beautiful chants of the Orthodox Church, without instrumental accompaniment, they sang four parts in perfect harmony.

The memory of their funeral services remains strong. There were solemn words in the church followed by the slow procession going up the stony path to the burying ground on the hilltop. They chanted the hymns as they carried the coffin. An emotional service was held at the gravesite. Artificial flowers, expertly made, were always in evidence when there were no real ones.

The hills of Sitkalidak Island, across the strait, were just as green, with bare gray crags above them and many turbulent streams running down the sides. Later, in exploring these hills, we found deep gullies where the streams came down, covered with luxuriant bushes, mostly salmonberries. It was fun to pick them, mostly from bushes over my head and berries as big as large strawberries. It seemed almost like picking cherries. We picked gallons and gallons, eating the fresh, and making jelly of some. They were too seedy and too watery to can whole.

The school was built to accommodate twenty-eight students. Stoves heated the building, and coal oil and gas lamps were used for lighting. In the summer of 1930, a play yard was cleared. Bookcases, a schoolroom cabinet, medicine cabinet, workshop, storeroom, and coal bin were built. In 1931, playground equipment was constructed and sewer connections were installed.

December 27, 1931

Dear Mother and Dump:

We are expecting a boat soon with mail, so I will have a letter ready to go back on her. I hope there will be lots of good news for us, my usual hope.

I have been wondering about your Christmas. It must have been a very quiet one for you, Mother, if you and Russ were alone. I suppose Dump had her new family with her, and Nan, too. Christmas tree ’n everything. [Marie had married Frank Wiley, a friend from her church. Frank had two grown daughters, Helen and Betty.]

We had a nice, quiet Christmas. It looked like Christmas, too. More snow than they have had here for years, several inches. There was bright sunshine during the day, and a brilliant moon at night, so the snow sparkled all the time in true Christmas style. The day before Christmas we had our little tree in the school. It lasted well, and looked quite gay with its decorations. The children did their little pieces. Much of the English could not be understood, but listeners did not know the difference. Everyone in the village came except one woman who was in bed with a new baby.

I was surprised by the gifts I received. This was the first tree and school entertainment they had ever had here, and I didn’t think they would know about gifts, but two of the women had been raised in a Baptist orphanage, and they got the rest of them started. They knew what was what. I got: four bags of bear gut—two trimmed with eagle feathers, one with bits of colored yarn, one with beads; a little basket woven of Native grasses, beautifully done; a homemade necklace; some kind of ring; an ermine skin; a very much worn fancy comb for the hair; a washed handkerchief; and a much worn “boughten” necklace.

The eagle feathers make the best trimming. Foster got a ladies new handkerchief. That night there was a dance in the schoolhouse, which everybody attended. There was a dance also the next night, but few came to that. Two dances in succession seemed too much.

Well, I’ll sign off until I get your letters, and then I’ll write again.

Lots of love,

Tetts

January 17, 1932

Dear Mother and Dump:

We are just finishing up the Christmas holidays. After our regular Christmas, there were all the Russian celebrations. Tonight the whole village masks and goes around from house to house to mystify each other. There can’t be anyone at home in most of the places except children and old folks, because everyone else is on the road. There is a continual procession of them in here and some of them are good. We are supposed to guess who they are, and we usually guess everyone in the village, beginning at one end and going right through. In that way, we are sure to hit the right one sooner or later. Some of them are so funny, I have laughed till my sides ached. They get a lot of fun out of it. They have done this masking every night now for over a week. Usually there was a dance, where different masked ones danced the Weasel dance, but tonight being Sunday, we will not let them dance in the schoolhouse, and last night being Saturday, and part of their Sabbath, they would not dance. As one of them expressed it, “The priest might give us hell.”

The first three days of their Christmas were strictly religious, church twice a day, and carol singers going from house to house with the Christmas star. That is a very pretty custom, and the singing is beautiful. I went around with them for two nights, and when they came here, I treated them to cake. It kept me busy baking, because I used three cakes each of the three nights, nine cakes, all iced, too. Tonight’s masking is different from the other nights. There is something about not seeing their shadows, so they back in, all wrapped up in sheets or blankets, and stand very solemnly until we guess who they are. Tomorrow there is a church service in the afternoon, and that ends their holidays. What tickles us is that the U.S. flag has been hoisted over their church at this time, and no other so far as we can find out, and the explanation is simply “holiday.”

We are more than anxiously looking for a boat from Kodiak tonight, because it has been more than a month since the last one was here, and we have been looking for it almost every day since New Year’s Day. The weather has been pretty cold and stormy for ocean travel, so I suppose that is the reason for the delay. The last few days have been delightful, warm and quiet, and a boat from Seattle was expected in Kodiak two days ago, so surely one must be on the way here. A trader’s boat stopped in here a few days ago on its way to Kodiak, and they took the mail for us, but they may not have connected with the Seattle boat. In that case, it will be a long time before you get my letters. I hope they did make connections. The next two months will be just about as bad, because they are stormy months, but after that, mail will be more regular.

Although we have had some cold and stormy weather so far, the winter, as a whole, has been a mild one. We hear over the radio of fifty below temperatures around Fairbanks and other places, but here, except for two nights, it hasn’t gone below zero. The radioman tells us of the queer freaks played by the weather in Alaska. At Takotna, there were seven feet of snow, and twenty-eight miles from there only seven inches. The temperature in one place rose over seventy-five degrees in twenty-four hours, from around fifty below to thirty above.

I’ll send this off, and answer your letters when they come.

I hope there will be many to answer.

With love,

Tetts

February 6, 1932

Dear Dump:

Yesterday your letter of January 12 came. That was pretty quick for this time of year. Last week we got mail that was almost two months overdue.

Mother’s letters sound so much better than they did, more natural. She did enjoy all the Wileys so much at New Year’s. Her letters were full of it!

I wonder if you have any old shoes with low heels that you want to pass on to me. It seems a shame to get new ones for this place. You get the new ones (joint account), and pass on the old ones. You know I am not “hard” on shoes. Last summer I bought a pair of shoes, the first I have had since I was home.

It is a gorgeous day, like May on the Yukon. Wish you could be here for a hike, the only form of entertainment we have to offer. But when we get our boat, we shall be kings of all we survey.

Love,

Tetts

April 2, 1932

Dear Dump:

Your letter with the bank statement, Book-of-the-Month News, and four books all came yesterday. Needless to say, I am delighted. Thanks for all your trouble. I don’t know what I would do without you. The Sherlock Holmes books are splendid. I have always wanted to read all of his, and I hoped they would send me Mr. and Mrs. Pennington. You see, I have time to read the book reviews, and so am able to keep up fairly well. I have read parts of Mary’s Neck and like it, so that is OK. However, I do not want all the novels. We are both rather serious readers. It isn’t often that Foster will even attempt a novel. He says it is a waste of time, but I would like Finch’s Fortune. I love the Whiteoaks books. And if you can get it, Kristin Lavrandsdatter, Then, Only Yesterday, The Doctor Explains, and Strange Animals I Have Known. I think that will do until the next bulletin comes. The trouble is, I want them all.

Sorry to hear of your neuritis, and I do hope it is entirely gone. Couldn’t you get a substitute for a time and come up here for a rest? I am sure this wonderful air and scenery would smooth out all the pains. There are absolutely no distractions here, the calm and peace are unsurpassed, and the stillness would not hurt your ears as at Tanana. There is the wash of the surf, the call of wild ducks and seagulls, the whistle of the winds through mountain draws, and the tinkle of streams down mountainsides.

I am sending you some film for printing, for yourself and the family. Of course, that means Mother and Nan, and be sure to pay for them out of the joint account. Three are taken from the mountain in back of us. The land opposite is Sitkalidak Island but doesn’t show the snow-capped mountains. Two pictures are of a bearskin hanging over a pole in a neighbor’s yard. In one, I didn’t get much of the head but the other seems to be all head. And one is of the beautiful little stream where we fished and berried last summer. These make good postcard-size enlargements, and I would get the enlargements if I were you, because they are too small to be seen well otherwise.

Take the Admiral Evans, Pacific Steamship Company. It sails every two weeks from Seattle. Please send me a set of postcard enlargements, but only one from the mountaintop. The more I think of your coming up here, the more I see that you must. Not only because you would like to, but because you should. I am convinced this can get you well as nothing else can, and you probably will spend the money for doctors, anyway. I’ll wager Frank agrees with me. I am writing the steamship agent to send you a folder. The Watson, too, probably comes to Kodiak in the summer. Let us know in plenty of time and we’ll meet you in Kodiak.

Come now.

Tetts

Two Alutiiq girls and a bearskin, Old Harbor, circa 1930s

May 24, 1932

Dear Dump:

Foster came home from Kodiak last night bringing, not you as we had hoped, but your letter of April 25th. I told him to open that in Kodiak to make sure about you. We were delighted with its news, except, of course, the BIG DISAPPOINTMENT. I noted that you were to send the cancelled checks and new bulletin, but there were other things to read and see about, so I did not bother about it until later today, and there, oh joy, another letter from you. So we feel that we have had a feast.

Your two books have not come yet, but I shall look for them eagerly. I have wanted to read both of them, especially Willa Cather’s. I must have been very vague about last month’s books. I DID get Mr. and Mrs. Pennington, long ago, and all the others right up to date. I take it Warden Lawes’s book is on the way, and you are right about that. I would not want to miss it. Sometimes the books are pretty wet, but that isn’t their fault. It is the sloppy seas on the way down from Kodiak.

Yes, the shoes came, and I put them right on and have worn them steadily ever since. They are just right for the house, and will last me for years, so don’t bother with any more.

No, my psychology did not work this time, not even with myself, because all along I have not once felt that you would be here, much as I would like to have you. We will concentrate now on you and Frank coming together sometime, and hope it will be soon. It is such good news that you are feeling like yourself again, and your letters sound like it.

Many thanks for all your trouble with my affairs.

Love,

Tetts

Etta and Foster’s success at their posts came to the attention of their supervisor at the Alaska Indian Service. In June, 1932, plans were made to transfer them to the isolated village of Kipnuk, 414 miles to the northwest on the Bering Sea. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, C. J. Rhodes, wrote: “Kipnuk is a new station being opened this fall. The building is in the process of construction at present. With reference to filling this position, Superintendent Garber wired, ‘Teachers for Kipnuk should sail via Tupper about August tenth. Please bear in mind complete isolation, difficult water supply, great destitution of Natives, and necessary Native health program in making your selection. Practical man whose wife is a nurse is the best combination for this place.’

Mr. Jones has lived many years in Alaska and is familiar with the isolation and hardships which exist at such a village as Kipnuk. He has had some pharmacy training, he has a great deal of experience in the operation of gas engines and gas boats, and is a practical carpenter. Mrs. Jones is a graduate nurse as well as a teacher. She has taught successfully in our Service for several years. It is believed that Mr. and Mrs. Jones will be an admirable combination for this new school, and it is therefore recommended that they be transferred as recommended above. It would not be desirable to send to this station persons unfamiliar with Alaskan conditions and whose training and experience have been largely academic.”

In a Letter of Justification from the Department of the Interior, Mr. Thomas wrote:

“For the proposed transfer of Foster Jones from the position of teacher at Old Harbor to the position of teacher at Kipnuk, Alaska.

The appropriation for Education of Natives of Alaska, 1931–1932, provided funds for the erection of a school building and teacherage at Cheechingamute, Alaska. The building material was purchased in Seattle and shipped with Cheechingamute as its destination. Due to difficulties of transportation it was not possible to get this material any farther than Kipnuk, at which point the material was landed. Kipnuk is a large Native village, and estimates had been submitted for the establishment of a school there for several years. Authority was therefore granted to erect the building at Kipnuk. The building is in the process of construction.

The salaries of two teachers were provided for Cheechingamute in the appropriation act for 1932, but the positions have not hitherto been filled due to delay in endeavoring to get the building material to its original destination and in its construction at Kipnuk.

There are at present thirty-four children at Kipnuk of school age and, with the establishment of the school, it is expected that other families will move to the village and that there will be additional children enrolled.”

In July, Etta received a letter from the Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, informing her that she was being transferred from Old Harbor to Kipnuk, a Yup’ik Eskimo village located on Kuskokwim Bay, one hundred miles southwest of Bethel.

Unaware that they would be leaving Old Harbor, Etta and Foster had made all the necessary arrangements to spend another year, including ordering a year’s supply of food. Careful planning was required when generating a list of food items that would be required for one year: thousands of cans, cases, barrels, and crates. Foster made the decision to leave the food supply in Old Harbor for the new teacher, and when they arrived in Bethel, just north of the mouth of the Kuskokwim River, forty miles upriver from the Bering Sea, Foster would pick up supplies there.