Читать книгу The Grasinski Girls - Mary Patrice Erdmans - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

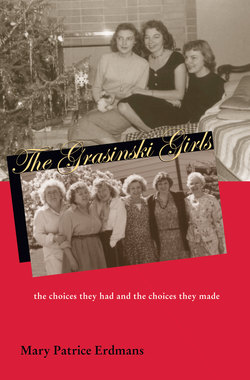

The Grasinski Girls

THEY HAVE BEAUTIFUL NAMES: Caroline Clarice, Genevieve Irene, Frances Ann, Mary Nadine née Patricia Marie, Angela Helen, Mary Marcelia. These are the Grasinski Girls. They are the daughters of Helen Frances Grasinski, and I am her granddaughter.

What I remember about my grandma Helen is that she was tall and she stood tall. She kept her shoulders back and chin high. I remember her as a wanderer. I have images of her getting on and off buses, in and out of cars, with a small suitcase that was actually just a big purse, as she traveled from house to house, one-bedroom apartment to one-bedroom apartment, daughter’s house to daughter’s house. Caroline, her eldest daughter, recalls, “Mom used to say, the minute she hears the freight train she wants to pack her suitcase and go. I really don’t know if it’s a thing, a place, or whether it’s something inside you, this wandering and searching and looking for something.” She moved eighteen times in her life. She was a good traveler, everything efficiently packed in that neat little bag, and she had an ability to make a place a home in a short period of time. Caroline continued, “She would be unpacked with all the pictures on the wall by the end of the day, and then she was sittin’ there.”

What I don’t remember about my grandmother, but what I am often told, is that she had a beautiful voice. I don’t remember her singing, but her daughters do. She sang arias while washing the dishes and folk songs while peeling potatoes; she sang Polish carols like “Lulajże Jezuniu” at Christmas and popular American songs like “Let the Rest of the World Go By” and “I’ll See You Again and I’ll Smile” while picking the grime out of the space between the floorboards with a safety pin. As a young farm girl she took voice lessons in Grand Rapids, riding twenty miles on the Interurban. She was a soprano, and if I close my eyes I can imagine a robust, resplendently piercing soprano, chin held high, neck straight, shoulders squared. At the age of sixteen she was given her chance. A professional impresario offered to take her to New York to become a concert singer. But her father said no. Instead, she married a local boy, Joe Grasinski, sang to her seven children, and spent the rest of her life moving here and there, around and about a sixty-mile ring of familial enclosure in southwestern Michigan.

Years later, Helen found her daughter—my mother—sitting in my bedroom listening to a scratchy Crosby, Stills, and Nash tape and crying, saddened by the fact that I had gone to live in Asia for a few years. She expressed little sympathy. “Why are you crying? You were the one who let her go.” As if she had a choice. But it seems that it didn’t matter if we were kept back or let go, both Grandma and I became wanderers and we both carry small bags. My orbit is a little wider than hers, but, like her, I keep returning home, never able to walk away and keep on walking.

. . .

Today, Helen’s daughters are called Caroline, Gene, Fran, Nadine, Angel, and Mari. Many of you will recognize the Grasinski Girls in your own mothers, aunts, sisters, and grandmothers. They are white, Christian Americans of European descent, and therefore represent the sociological and numerical majority of women in the United States. Born in the 1920s and 1930s, they created lives typical of women in their day: they went to high school, got married, had children, and, for the most part, stayed home to raise those children. And they were happy doing that. They took care of their appearance and married men who took care of them. Like most women in their cohort, they did not join the women’s movement and today either reject or shy away from feminism. They do not identify with Betty Friedan’s “problem that has no name,” and they are on the pro-life side of the abortion debate.1 They give both time and money to support charitable (usually religiously affiliated) organizations working to ease the suffering of those less fortunate.2 Most of them go to church every Sunday and they read their morning prayers as faithfully and necessarily as I drink my morning coffee.

The Grasinski Girls’ immigrant grandparents were farmers. Their father was a skilled factory worker, and their children have college degrees. Their Polish ancestry is visible in their high cheekbones and wide hips, but otherwise hidden in the box of Christmas ornaments stored carefully in the attic. Theirs is a story of white working-class women.

Who are these women who sing in church pews, hum in hallways, and cry to sad songs about miseries they do not have? Do we see their curved backs tending gardens in the backyard, or bent over sewing machines or dining room tables cluttered with their latest craft project? When I read social science literature written before the 1970s, I read mostly about men—and mostly white men. Since then we have heard more women’s voices, mostly the voices of white middle-class women. But again, that is changing, and now we hear from and about black women, Latinas and Chicanas, Asian women, and Native-American women, as well as low-income women, homeless women, and immigrant women. Traditional gender studies ignored class and race when they developed theories about all women based on the experiences of white middle-class women.3 Contemporary gender studies are more likely to acknowledge race, but too often they obscure class by folding it into race. For example, Aida Hurtado states, “When I discuss feminists of Color I will treat them as members of the working class, unless I specifically mention otherwise. When I discuss white feminists, I will treat them as middle class.”4 When combined with those of white middle-class women, the voices (and disadvantages) of white working-class women are lost. A similar confusion occurs when white working-class women are grouped together with working-class racial minorities and immigrants. In this case, however, white native-born privilege gets overlooked.

When the voices of white working-class women are heard, they are more likely to be public and “classed” voices related to labor-market position. Social scientists generally examine social life in places where they can see it, that is, in the public sphere (e.g., the workplace, the neighborhood association, government offices). Public-sphere activity is also easier for scholars to grasp and write about because it is normative.5 Donna Gabaccia found that immigrant community studies “do not ignore women but describe mainly those aspects of women’s lives (wage-earning and labor activism) that most resemble men’s. Distinctly female concerns—housework, marketing, pregnancy or child rearing—receive little or no attention.”6 As a result, we hear working-class women chanting protests in front of factories and challenging public officials at neighborhood meetings, but we seldom hear them praying in the early dark of morning or laughing with their sisters in the warmth of the kitchen.7

While the Grasinski Girls moved through the public sphere as secretaries, nurses, cooks, teachers, and den mothers, they constructed their identity mostly in the domestic sphere. To begin to understand their worldview, I visited with them in their kitchens, living rooms, dining rooms, bedrooms, and local parks. Over a period of four years (1998–2002), I listened to and recorded their stories. I then constructed their oral histories from these transcripts. Then, they reconstructed my construction. Together we hammered out a representation and an analysis of who I thought they were and who they wanted to be seen as.

. . .

Every phase of my life, just wonderful things have been there, I have to admit it. Well, there are some mistakes you always make, but basically, I mean I liked the way I live, what life has given me, what came from that little farm girl.

Nadine

The Grasinski Girls tell stories of contented lives with abundant blessings, a God who loves and protects them, and children who are healthy. “I don’t think there is anything I would have changed or say I regret. God has been good to all of us,” Fran writes to me. They experienced no great tragedies but instead lived “ordinary” lives. Sure, there have been ups and downs, but they pretty much, in all categories, fall in the middle of the bell curve. They are “normal,” and social scientists have not studied normal very much. Perhaps this is because the life of the average Jane is not as compelling as that of the exotic Jane. Perhaps it is because stories that are seductively sensational are easier to sell.8 A less cynical reason that ordinary lives are not researched is that they do not present “social problems.” Social scientists more often study populations and institutions that are troubling and cry out for solutions (e.g., drug addiction, suicide, domestic violence). But what are we missing when we focus on the extremes and ignore the more subtle ways that social structures constrain lives? And what are we missing when we focus on discrimination but not privilege?

When privilege is taken for granted, it is not placed “under the microscope” for examination, and the absence of problems becomes defined as “normal” rather than as privilege. When, instead, we focus on the “normal,” as Ashley Doane has done, privilege becomes visible and we can see those otherwise hidden ways that the political and economic structures relatively advantage certain populations.9 Alternatively, when we focus on extreme oppression, we miss the subtlety of inequality. When we study horrific problems, we amplify social life so that we can hear it more clearly. Domestic violence shouts “patriarchy.” But where is the whisper of patriarchy that robs women of the opportunity to develop their full potential? In the same way, when we study social movements, we see individuals publicly working to change social institutions, but not the nudging of resistance in our private lives. How does resistance operate in the kitchen and the bedroom? How do people challenge structures of inequality in their everyday routines? And, conversely, how do their routines reproduce inequality?

In telling the stories of the Grasinski Girls, I try to make visible their privileges hidden under the cloak of normalcy as well as the nuances of oppression often overlooked. Their contented life stories made it easier for me to see their privilege than their oppression. Moreover, they construct narratives of happiness that undermine discussion of oppression. In fact, they do not even like the word oppression appearing in a book written about them. One of the sisters, commenting on a draft of the manuscript, said, “This oppression, this is the one thing that we didn’t feel. It just seems like it’s brought up so much. You see, it’s very hard for you to go back in time to where we were. You’re putting feelings into us that were not there. We didn’t feel like we were oppressed. It wasn’t that we didn’t recognize it, it just wasn’t there.”

They have wonderful lives, they say. While there were some dark moments, they shied away from bruised areas, and did not dwell in the valley of darkness. Have faith; be happy! That’s their motto. Why? I wonder. Why do they insist on constructing happy narratives, and how do they go about achieving happiness? Happiness is not the absence of sadness but an ability to live with sadness and still see the beauty of the day. To breathe deeply and inhale the gray wetness of rain as nourishment, the white thickness of fog as misty backdrop. To be happy is to smile even when you don’t get your way, to be grateful for the gifts you have been given. To be sure, happiness may be correlated with privilege—the more one’s needs are met, the easier it is to be happy. But, for these women (and, I suspect, many others), happiness is also a modus operandi, and one of their life tasks is to figure out how to be happy.

While the sisters wanted me to present them as women who were happy, I wanted to present them as tough women who, even when things weren’t going exactly right, figured out ways to live satisfying lives. Perhaps they didn’t change the world, but they had the social competence to live in the world with dignity. They rejected many of my attempts to portray them, or their mother, as feisty, defiant, or discontented. They were not fighters, they said, but peacemakers; they were not wanderers, but homemakers. Even if they were less than happy at times, they did not see my point in focusing on that part of their lives.10 As one sister said, “If you are going to say it, put it somewhere in a little corner, don’t broadcast it and emphasize it,” because the unhappy parts were not representative of their lives. They were privileged, they say (“blessed” is their term, because God, not social structure, is the prime mover in their worldview).

They were privileged by race and to some degree by class. They had, for the most part, economically stable and comfortable lives. As adults, some moved into the middle class, and even those in the working class lived well; they were certainly not poor, not even working poor, even if they were on tight budgets. And yet, growing up, they did not have the opportunities that the middle class offered—for example, the encouragement and means to continue their education. Moreover, they were not given (though some did acquire) the dispositions, routines, and linguistic styles of the professional middle class. They were also disadvantaged by their gender identities—at least my feminist perspective leads me to believe this. So do many of my colleagues, who shook their heads at these women’s constructions of a “blessed” life, saying, “they have a revisionist history,” “they are suffering from false consciousness,” or the “opiate of their religion is really strong.” You may also be suspicious. You may think that because I love and respect my aunts I won’t tell their whole stories—warts and all. You are right. Weren’t there more failures, sorrows, and ugliness? Yes. How complete is the story I am telling you? It is partial. How truthful is the story? There are sins of omission but not commission. There are no falsehoods or deliberate attempts to mislead you. I respected their right to construct their life stories as they wanted—if they wanted to leave out some parts, so be it. My question was, why did they construct their narratives in the way that they did?11 Why do they want to present themselves as happy women—and how did they achieve, to varying degrees, their happiness?

Their happiness is partly a consequence of their position of relative privilege via race and class identities, but it also comes from their own actions, what sociologists call agency, their potential to construct the worlds within which they live. Their mother and their grandmother taught them how to sing and how to pray, how to plant flowers and how to suckle children. They also taught them how to be women: to depend on their selves and their Jesus to make them smile; to be strong, like the Blessed Virgin Mary, especially when things are bad; and to define their lives in the private sphere, in the family. The Grasinski Girls did not passively and blindly accept the insults of gender and relative class inequality. Instead, they resisted—not by joining social movements, but by planting gardens and listening to love songs, taking driver-training courses and using lawyers to help collect child support payments.

Black women writers like Patricia Hill Collins, Paula Giddings, and Audre Lorde taught me to look for resistance in places that no white male authority or traditional sociologist taught me to look: in the belly, in the backyard, in a late-afternoon conversation.12 Even thought can be resistance. Refusing to engage in self-blame or refusing to believe negative messages of inferiority are ways of resisting oppressive cultures. These women claimed freedom by not embracing the competitive, alienating values of the public sphere; they claimed space in the house by taking over the kitchen table with their projects; they claimed power through generations by arguing for their daughters’ right to move more freely in the worlds of work and love.

What I am calling resistance, some historians have called accommodation. Eugene Genovese, writing about slavery, defined accommodation as “a way of accepting what could not be helped without falling prey to the pressures for dehumanization, emasculation, and self-hatred” and suggested that accommodation “embraced its apparent opposite—resistance.”13 Accommodation is a non-insurrectionary form of resistance, a resistance that does not attempt to overthrow the system, but, at the same time, does not submit wholly to the humiliations of subordination. While it does not challenge the objective conditions of inequality, it does help prevent the internalization of inferiority. Even if the resistance takes place only in the mind, accommodation, as an adjustment to social conditions, implies action not docility, agency not resigned acceptance. This response to structural conditions offers both dignity and a modicum of happiness.

For the Grasinski Girls, the mind and the family were sites of resistance. Patricia Hill Collins argues that women often use existing structures to carve out spheres of influence rather than directly challenging “oppressive structures because, in many cases, direct confrontation is neither preferred nor possible.”14 The Grasinski Girls did not disrupt the balance of power, but they did create private worlds based somewhat on a set of values that ran counter to those that dominate public space. Whether conscious of it or not, their domestic routines and commitment to motherhood, while complementing men’s work in the public sphere and thereby reproducing gendered status and capitalist relations of production, nonetheless tempered the arrant commercialization of the private sphere. Their moral careers as mothers, caretakers, and spiritual teachers valued affective rather then instrumental relations, placed people before profits, and embraced the nonmaterial and noncommidifiable forms of religious devotion.

. . .

Once, I was sad about a problem I was having with a relationship that stemmed, I believed, from larger structures of gender inequalities. I was crying and wanted some female empathy, so I called home to my mother. I poured out my woes and feelings of anger, sadness, and depression and then asked, “Mom, haven’t you ever felt this way?” She paused, coming up with nothing at first, but then said brightly, “Maybe you’re pre-menopausal.”

In trying to tackle these two tasks—explaining the lives of these ordinary women who represent the majority of women in America in their age cohort, and trying to understand their laughing personas—I landed in the middle of an epistemological funk. How do I step out of my worldview, my set of values, my matrix of perception, to see them as they see themselves, to understand them from their social location rather than from my location?15

The Grasinski Girls live in a world of colors, texture, shapes, and aromas; they live in an emotional world where sentences are punctuated by laughter and tears. They live in a caring world where the relationship comes before the self, and the self is found in the relationship. They live mostly at home. In contrast, I live in the public sphere, in an academic world made up of words and arguments, thoughts and books. I live in relationships, but my identity also is shaped by my profession. I live in a world of competition and ambition. My life is oriented toward seeing inequality with the purpose of changing it; their lives are oriented toward cultivating happiness in the social house into which they were born.

They live in a world very different from my own. At first I could not reconcile how my view of the world and their view of the world could be so different without one of us being wrong. And so I challenged their contentment, their belief that women have more power than men, their desire to stay in the private sphere. I challenged their playing dress-up with life; I challenged their days defined by how many pounds they have gained or lost and how good they still look. I challenged their “life is grand, cook him a good meal, believe in Jesus” brand of living. I wanted them to be feminists, to not be so concerned with diets and clothes, to understand gender and race and class inequality and to do something to fix it. I wanted them to stop coddling men and start thinking about themselves. I did not necessarily like the way they were women, and I think a part of me blamed gender inequality on women like them, women who throw like a girl and can’t drink like a man.

They challenged me to see them without judging them by my standards, my values, my routines. Comparing their generation to my generation is different from judging their generation based on the values and beliefs of my generation. They struggle and resist, not in the way I do, which is to fight to join the man-made world. Instead, they fight to preserve their private, female world. My job as a sociologist was to try to understand their world. In some ways, it felt like going into foreign territory, in other ways, like I was coming home.

Our understanding is shaped by our position in the social order and embedded in the relation between the object (what we seek to know) and the subject (ourselves). Sociologist Karl Mannheim refers to this as relational knowledge.16 Relational knowledge is not false knowledge, but partial knowledge. It is a view of the world from a particular social position or, as some feminist scholars refer to this, a particular standpoint.17 The relevant epistemological and sociological questions are not about the veracity of knowledge but the social base of knowledge: Why do they think the way that they think? Why do they see the world the way that they see the world? What aspects of social structure shape how they perceive and understand their world?

Each generation has different opportunities, different perceptions of those opportunities, and, as a result, different choices. I want to both understand the world as they see it, and, with generational distance, frame their lives in historical-structural context. But when I use my frames—the frames of an educated professional woman who came of age in the 1970s—to understand the lives of these women, I am not hearing them, I am hearing myself. As is often the case, travel into foreign lands teaches us mostly about ourselves. And so, writing about their generation laid open my generation; trying to understand their lives, I could better see the value structure underlying my own standpoint.

Understanding knowledge as standpoints (theirs and mine) produced more egalitarian relations because the production of knowledge became the sharing of standpoints. I have tried to let you hear both their voices and mine, to give you their objections to my interpretations as well as my objections to their narrations.

. . .

Dear Mary Patrice,

Sending you a few things. Upon seeing you last, I think the Grasinski Girls are wearing you out. It’s difficult to write about people who see themselves one way, [different] than the way others see them.

I love you, Nadine

The Grasinski Girls guided this work. I would give them drafts and they would say, “No, that is not who I am!” “Where are my children? Put my children in the book!” “Tell them I love being a mother, did you say that, did you tell them I love being a mother?” One sister wrote to me early on that she was suspicious of my intentions: “We are not women with flabby arms flapping in the wind while we bake our apple pies.” Don’t insult us! I tried not to, and toward that end I gave them the right to edit the manuscript.

The participants in qualitative studies are always at least indirectly coauthors, in that they construct their story from which the social scientists construct their story. But this was a collaborative project in more explicit ways. The Grasinski Girls had ownership of their printed words. The collaborative, egalitarian structure of the project was a result of (1) the recognition of standpoints; (2) the fact that I was going to use their real names; and (3) the knowledge that I would always be going home for Christmas. Because of my intimate attachment to these women, I could not temporarily enter into their community, gather information, and then leave. There would be consequences to my writings in ways that mattered to me. I did not want to hurt them, so I could not go for the jugular. I could not reveal their deepest demons, their humiliations and unnamed fears—those were between them and Jesus. This is not a “tell-all” biography. I did not write this to expose them but to better understand the private worlds of white women in this generational cohort. Moreover, given my position as intimate insider, my mom and my aunts did not have the same privilege of withholding information as do strangers we encounter in the field. I know things about them that they could have kept hidden from outsiders. This ethically required a more restrictive reporting strategy. I had to allow them to edit out material that they felt made them vulnerable.

Some of my social science colleagues worried that I gave the Grasinski Girls too much control, and that their stories would be too “constructed” in a way that implied falsehood. But anthropologist Clifford James argues that ethnographies are always constructed truths shaped by the politics of the academy and the observer, and they are always partial, but not necessarily false. He writes, “All constructed truths are made possible by powerful ‘lies’ of exclusion and rhetoric. Even the best ethnographic texts—serious, true fictions—are systems, or economies, of truth. Power and history work through time in ways their authors cannot fully control.”18 Our understandings of the world are always shaped by paradigms and ideologies (hidden or visible), as well as taken-for-granted privileges and power. We are mistaken if we see only the paradigms and partial truths of the people of study, and not those that belong to the social scientist. We all look at some parts of the social world and ignore others. We manipulate data to argue a point or minimize conflicting data to emphasize analytical categories. We construct theoretical questions to fit with the methods that we know. We censor the solutions we propose according to the political ideologies we espouse.

In this study, the Grasinski Girls’ life stories were constructed in the relationship between us, and in that relationship I was a niece and a daughter. As such, it felt odd and ineffectual to use only a traditional academic style of writing which, as Susan Krieger notes, “is designed to produce distance and to exclude emotion—to speak from above and outside experience, rather than from within.”19 Sociological language seemed too stark and sterile to be able to describe Aunt Caroline’s wheat-colored baskets of overflowing dried flowers cascading from the tops of large wooden cabinets, or Aunt Nadine’s rich desserts that are not too gooey, not too chocolaty, but have a lingering sweetness that makes me hold them on my tongue and groan, reluctant to swallow. When speaking from within, the complexity of the world is magnified by closeness. When we look at ourselves, or people who are close to us, the intimacy breathes contradictions and defies stark categorization: we can love and hate the same person, we resist and roll over in the face of oppression, we are both privileged and disadvantaged. The distant social scientist can more easily see individuals as social categories. But when I write about my aunts, I cannot see the categories for the faces.

What price did I pay for this closeness? While this insider knowledge made me privy to a lifetime of glances, nods, and stories that they do not want told to nonfamily outsiders, how does the fact that they are my mother and my aunts, for heaven’s sake, interfere with my ability to “get it right?”20 Sociologist Robert Merton notes that the problem of being an insider is that the myopic vision obscures the interpretation. “Dominated by the customs of the group, we maintain received opinions, distort our perceptions to have them accord with these opinions, and are thus held in ignorance and led into error which we parochially mistake for the truth.”21 But Merton also argues that in every situation researchers are both outsiders and insiders, and outsiders err by mistaking their own paradigms for the truth. Too close, we have distortions; too far, we have misunderstandings. The best we can do is work to correct our near- and farsighted visions.

My distortions come from a deep respect for the working class and my love for my family. Sharing my work with other academics helped adjust for this myopia. My misunderstandings are found in my feminist framework, which was critical of the Grasinski Girls’ life worlds. I’ve tried to correct this by including in the text their responses to my interpretations as well as my objections to their responses. Ironically, the feminist stance that created the potential for misunderstanding also provided a corrective. Feminist inquiry rejects the methods of traditional science based on a positivist model which posits a duality between object and knower, and instead promotes methodologies that bring the researched into the research process to both minimize objectification and make evident the subjectivity of the researcher.22 Allowing the Grasinski Girls to comment on and edit the manuscript helped correct the biases that arose from my outsider (academic and feminist) stance.

. . .

I want this story not only to be about them but also to reflect them, to contain their affective, textured life of color, taste, sound, and light, to embody the warmth of thick breasts and fleshy arms. I want you, the reader, to meet them, giggling and jiggling and not finishing sentences, losing their selves in mixed pronouns, talking about “you” when they mean “I” and rearranging and reinventing the English language so that they can say what they want to say. I want you to see how they created space for themselves at their kitchen tables, found and lost their voices by talking and silencing each other, and maintained their happy faces by singing and praying and wearing lots of makeup.

To better hear them, I chose to use long passages from their oral histories, and to keep the words in their spoken form. Oral speech is less formal than written speech and captures their kitchen-table style of talking. To make the narrative more readable, I edited out many of the dead-end sentences and tried to tame the rambling, disjointed nature of conversation. I spliced sentences together, sometimes dialogue that was pages apart, because I wanted to keep intact the thread of the story. What I did not do, however, was “clean up” their language. I kept the rhythm of the oral speech, for example, the repetitions and partial sentences; I also kept the double negatives, the noun-verb disagreements, and a lot (but not all, or even most) of the filler phrases such as “you know,” “like,” “watchacallit,” as well as the elided and blurred nature of oral speech (for example, “gonna,” “wanna”).

My intent from the beginning was to “give them voice.” I wanted to empower them by letting them narrate their lives on their own terms in their own voices.23 But the stories told in their own words while sitting around their kitchen tables became “sort of funny looking” when “we see it on paper, and we don’t like it”—especially when their informal, spoken words were placed next to my formal, written, professional language. Stuff that could be fixed, like poor grammar, they wanted me to fix. They wanted this for the same reason they put foundation on sallow skin or brighten their eyes with eyeliner. They didn’t want a face lift, just some eyebrows. One sister said, “like, you always say ‘gonna,’ and I don’t know if you did that purposely because you say that all along and it sounds like a hillbilly talking.” As a result of exchanges such as this, I took most of the “gonna’s” out of their text. As for the grammar mistakes, they all had a chance to edit their words. They did things like replace “kids” with “children,” and “stuff” with “things.” Some took out their double negatives. When they caught their own mistakes, I changed them. When one sister caught another sister’s mistake, however, I did not fix it.

Some of them tried to rewrite their narratives, or at least large chunks of them, but I would not substitute written autobiographies for oral histories. I took some of their written comments and included them in different parts of the manuscript, but I always labeled them as written. For their life stories chapters, however, I pleaded with them to keep their animated, spirited style of oral speech, reassuring them that it did not sound “bad.” I gave them pep talks about how the repetitions in spoken speech serve as emphasis, tone, mood, emotion, and that these are “typical” of spoken speech—they are “normal.”

ME: There’s nothing wrong with your words. You can communicate very well. It’s not about using fancy words.

GG: You make me feel good because everyone always told me I didn’t know too much.

ME: Using big words—

GG: —doesn’t mean everything.

But using big words usually does mean something. It is one way that people signal their education as well as class position.

It is not just the content of their stories that describes what it is like being white working-class women. The form of their storytelling also shows us who they are, by making more evident their class location. This was another reason I used oral histories, and another reason they felt somewhat demeaned by this project. One sister said, “You shouldn’t have left all those words like ‘cuz’ and ‘watchacallit.’ I know what you’re trying to do. You’re putting us in a class that you feel that we were in, kind of uneducated or kind of behind or something.” Another said, “I didn’t know you were going to take [us] word for word, I thought you were going to put it in your beautiful flowery writer’s language. [laughs] And then again, I didn’t really like the reason why you did it because you’re like putting us with low poor-class people [laughs] and I didn’t want to be portrayed like that.”

I never intended to put them in a “low” or “poor” or “uneducated” class of people. All I said was that I wanted to show their working-class roots, and this was seen as denigrating them.

The Grasinski Girls do not identify themselves as working class, but as middle class. One sister continued to make notations in the margins whenever I mentioned that her father was a tool-and-die maker, writing, “He worked himself up . . . he got so he was wearing white shirts at work. He was the boss.” In Mari’s story, she talks about her reluctance to define herself as working class because it meant that she had not moved up in class from where she started. I asked Angel, the wife of a skilled auto laborer in Michigan, what she considered her “social class,” and she said, “middle white class.” I followed up: “Who is working class?” She answered, “That’s all my friends. I think of all my friends as working class, people who work their whole life, nothing was ever given to them. Middle and working go together in my mind.”

Class is one of the more unspoken oppressions in the United States. One way we avoid looking at class inequalities is by assuming we are all middle class (except the undeserving poor, the ideology of individualism argues, who could be middle class if they would only get a job). Lillian Rubin contends that the working class gets lost when it is “swallowed up in this large, amorphous and mythic middle class,” which in 1990 was defined by the Congressional Budget Office as including any family of four with an annual income between $19,000 and $78,000.24 Within these brackets the Grasinski Girls were all middle class.

Social class is a muddy category, as one’s location is determined not only by income, but also by education and occupation (and this almost always refers to paid labor). For married women like most of the Grasinski Girls who are primarily engaged in unpaid domestic work, the social class of the household is determined largely by the husband’s income and occupation.25 Class also has ragged edges because democratic societies allow for some mobility over the generations, so that the class location of adulthood can differ from that of childhood. Moreover, classes bleed into each other, the working poor into the stable working class, into the lower-middle class, into the middle-middle class, and so on.

And yet, despite these complexities, ambiguities, and fluctuations, class differences are nonetheless real. While the economically stable working class and the lower-middle class may share the same income, neighborhoods, and schools, the skilled union worker has a different relation to production than the retail manager or small business owner.26 While the sisters had different childhoods (e.g., some experienced the Depression, while others did not), they were raised by the same parents, whose level of education and cultural routines were shaped by their own class and ethnic background. Despite the fact that they have had different adult experiences (one needed food stamps, and another lives in a chateau; some have college educations, and others high school diplomas; some married men who have professional occupations, while others married tradesmen), their class background shaped their choices and their dispositions. The psychological dimension of class is “learned in childhood,” Carolyn Steedman argues, and the emotions and scripts that we learn stay with us long into adulthood.27

Class provides cultural capital as well as material capital, and cultural capital (social skills, linguistic styles, tastes, preferences, and habits) is quite durable.28 These repertoires of cultural and mental routines are taught to us by parents, teachers, and peers, and learned and practiced in institutions—in particular, the educational system. As such, our class backgrounds are encoded in linguistic and cultural practices. I left their language in the truest form possible so as to illustrate their class location and gendered personalities as encoded in the rhythms of their speech, their vocabularies, and their grammar. But they wanted their language changed for the same reason I wanted it preserved—it revealed class identity and education level.

With their speech kept as it was spoken, it felt as if their words had betrayed them, or that I had betrayed them.29 But for what reason? In the 2001 National Basketball Association playoffs, Allen Iverson of the Philadelphia 76ers referred to something as “the most funnest.” That grammar mistake was repeated in broadcasts numerous times over the following weeks. Why was it so necessary to repeat that phrase? What were they trying to do, show the world that his command of English was not as good as theirs? Was it a racist insinuation? Perhaps the Grasinski Girls thought I was doing the same thing, that I was looking for their class colors in order to insult them. But I don’t show you these women to ridicule them. I reproduce their language in its original (sometimes grammatically incorrect) form because that is how they speak. I wanted to capture their class culture as manifest in their language styles and to be as true as possible to their experiences, and I didn’t think that my professional speech alone could adequately reflect their everyday being.

Unfortunately, my naive attempts to produce egalitarian relations were derailed because I forced them to play my game—the academic game. Their spoken language is perfectly suitable for kitchen table discussion; it is the book context that makes it appear inadequate. I was trained to write, and that gives me power in this arena. As one sister said, “You write very nice. Of course you do, because that’s what you do. I mean that’s your education and that’s what you do.” Moreover, I can edit my formal language (and edit and edit and edit) and draw on my professional networks to make my written words read better—colleagues, publishers, copy editors all read the manuscript and cleaned up my language. I definitely have more power in this setting to shape my presentation of self than they do.

Given that I am a professional writer, I could have made them sound “better” than I did. And, given that I was family, maybe I should have. Yet, I thought that they looked damn good the way they were, and that in life, as in this book, they wear too much makeup. But then, they most likely think I don’t wear enough.

. . .

In this book, I am interested in what C. Wright Mills calls the intersection of biography and history. I begin with the story of Frances Zulawski. Born in Chicago to Polish immigrant parents, she moved to a Polish farming parish in southwestern Michigan, where her father arranged her marriage. Her fourth child, Helen Frances, born in 1903, married Joseph Grasinski, and together they had seven children—six of whom were girls, the Grasinski Girls. The life grooves that were available to these Roman Catholic working-class American girls of Polish descent who came of age in the 1940s and 1950s started at the altar: marriage to God or marriage to a man. While the feminist frameworks in the 1970s challenged their ways of being in the world, they resisted both the negative patriarchal definitions of women and the feminist devaluation of the choices they made. These women struggled to assert their needs, carve out alternative life routes for their daughters, and retain dignity and pride within the worlds they actively constructed. They carried Christmas trees home on city buses, found open seats in crowded churches, and survived emotionally by developing a thick skin (something the next generation would require Prozac to accomplish).

Fig. 1. Caroline in front of her home, 1979

While the Grasinski Girls represent a gender cohort (modified by class and race) and therefore share values and behaviors, the six women are also different, in part because their birth dates span twenty years, but also because of class mobility and educational achievements.

Caroline Clarice (Caroline), the oldest of the sisters, remains rooted in the family home in the ethnic farming parish that was the ancestral site of Polish immigrant settlement in Michigan. In 1942, at the age of nineteen, she married a Polish-American boy from the community who had just been drafted. Together they had three children. Her husband supported the family comfortably on wages from his skilled, unionized position in a subsidiary to the auto industry. She stayed home and cared for the children until her midfifties, when she took a full-time position cooking school lunches at the local parochial school. Caroline lives with her hands: in the dirt growing hydrangeas and irises, weaving baskets, baking raisin-laced breads, sewing banners for the altar, and making crafts to sell at church bazaars.

Fig. 2. Gene and Fran, c. 1946

The next daughter, Genevieve Irene (Gene), died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1962 when she was thirty-six years old. She never married and never had children. Gene was an “A” student in grade school. She entered the convent after the eighth grade, stayed one year, and then returned home and worked as a domestic instead of completing high school. Later, she took secretarial courses and worked for an insurance company. Gene is remembered for having the best wardrobe of the sisters (her paycheck afforded her this), taking pictures of the family, and playing the piano. The older sisters are protective of her memory, and, without her own voice, I had to surrender to many of their edits regarding Gene’s life.

Frances Ann (Fran) knew Gene the best because she was closest to her in age and they lived together for several years before Fran married a Czech American from Cleveland. Her husband earned an accounting degree (on the GI Bill) and they moved into a middle-class neighborhood where they raised three children. Fran dresses in expensive clothes that are easy to remember: a classically tailored beige short set, off-white pleated skirt and soft cashmere sweater, a jacket of rich burgundy and rust. She gets her hair done once a week and always has a well-cared-for public face—tasteful makeup, fashionable glasses, attractive jewelry. She does not drive and never needed to work (although she was an antique dealer for a while). She has had a comfortable and privileged life centered around her family and the church.

The only son, Joseph Stanislaus (Joe), was born after Fran. His sudden death at the age of fifty-eight (he died from lung cancer only six months after diagnosis) was one of the Grasinski Girls’ greatest sorrows. His sisters feel “a special kind of love for him.” He was talented musically and artistically, and, like his mother, he was a wanderer. He lived in Arizona and Colorado before returning home to southwestern Michigan. He married and had four children and eventually designed and built a house near the Polish farming community of his childhood. He was a country-and-western singer early in his life and later became a commercial artist; when his company downsized and he was laid off, he reinvented his career, first as a prison warden and then as an auctioneer. Joe had an empathetic personality, a brilliant, flashing smile, and a hearty six-foot-three laugh. His sisters wanted a whole chapter devoted to their brother in this book. I compromised and gave them this paragraph.

Joe was closest in age to Patricia Marie, who took the name Nadine when she entered the convent. Nadine was a Felician nun for twenty-two years, during which time she earned a master’s degree in home economics. After she left the convent, she kept the name Nadine, and acquired a French surname when she married a former priest. At the age of forty-five she conceived and delivered their only child. They built a winery and bed-and-breakfast near the upper peninsula of Michigan and today live as a modern-day baron and baroness. She challenges this description by noting that they “both work all day” running the business—and they do. She prepares gourmet breakfasts for the guests, and sews items she markets under the label Nadja. One sister describes Nadine as a “Russian countess.” I see her as Polish. She has high cheekbones, a gracious manner, and almond eyes. Her clothes are detailed with ruffles and gold lamé, and, at the age of sixty-seven, when she walks into a room, people still turn their heads.

Fig. 3. Nadine in front of her home, 1977

Angela Helen (Angel), the second youngest daughter, also started her adulthood as a Felician novitiate, but she left the convent after a year. She married the boy next door, a Dutch-Polish American, and together they had six children. Angel is located solidly in the working class. Her husband, a tool-and-die maker, worked forty years in the auto industry before he retired at the age of fifty-eight with a comfortable pension. Angel worked on and off as a secretary so that they could save up a down payment for a house, convert the basement into a family room, and buy a new car. She and her husband like to gamble in Las Vegas and take three-week group tours of Europe. For over forty years they have lived in the same house in a well-maintained, white working-class neighborhood of ranch homes built in the late 1950s.

Fig. 4. Angel in front of her home, 1967

Fig. 5. Mary, Angel, and Gene at their home, 1952

Mary Marcelia (Mari), the youngest daughter, straddles the decades of the happy housewife of the 1950s and the return-to-college feminist of the 1970s. Like many white working-class women in her generation, she married a few years out of high school. She put her Irish-American husband through college and professional school and raised their four children. By her midthirties she was divorced and back in school. She earned a degree in fashion merchandizing, but never had an opportunity to develop this career. She worked instead as a nursing assistant. In midlife, she changed her name from Mary to Mari, moved to San Francisco, married a Filipino, and moved again to Manhattan where she lived for more than fifteen years with her husband before retiring to Phoenix.

These are the Grasinski Girls. Some will object, I assume, or at least wonder about the use of the term “girl” to describe the lives of women. Let me say first that the sisters themselves do not object to the term. I use “girl” because it captures their laughing personas, their gaiety and lightness, and, in many ways, the frivolity that comes from a combination of privilege (race and relative class privilege) and disadvantage (the “silly” gender). I also like to use the term because doing so subverts the power of the dominant group by co-opting a term that subordinates women. But this is not why the Grasinski Girls like the term. As “strictly a female female,” they all simply “enjoy being a girl.”30