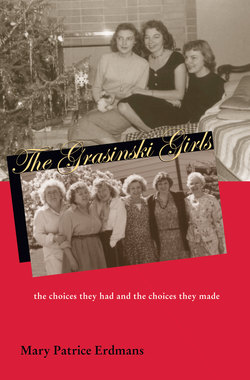

Читать книгу The Grasinski Girls - Mary Patrice Erdmans - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Mothers of the Grasinski Girls

We make our history ourselves, but, in the first place, under very definite assumptions and conditions.

Friedrich Engels, letter to Joseph Bloch

Frances of Hilliards

In her wedding picture, Frances Zulawski Fifelski, the grandmother of the Grasinski Girls, looks young and apprehensive. She was a short, slight woman, only ninety pounds and less than five feet tall. The yards of cloth that make up her wedding gown add a plumpness that foreshadows her matronly thickness. Her small frame is dominated by a giant corsage that covers half her chest and a limp bouquet in her right hand (the pictures were taken on the third day of their wedding). Both Frances and her husband Ladislaus Fifelski look past the camera lens. No smiles—that was the style back then. Her left arm rests tentatively on his shoulder. She was fifteen when they married in 1898. He was almost twice her age. Her father had arranged the marriage, and she agreed to it. No stories of passion are passed down through the generations. Frances and Ladislaus were introduced, they married, and they had their picture taken. Within a year a child was born, and Ladislaus kissed her for the first time, or so the story is told. In the wedding picture, he sits stiffly in a high-back chair. His brow is unlined, his face clean-shaven, the black suit just a little too short in the sleeves, his collar starch-white.

Ladislaus’s family arrived in Hilliards about the time the church trustees were getting arrested for selling beer at the church fair. Frances didn’t get there for another six years, and when she came it was to marry Ladislaus. The oldest child of Krystyna and Pawel, Frances was sickly and weak from having contracted diphtheria as a child. After finishing eight years of schooling in Chicago, at the age of thirteen she entered the Felician convent in Chicago. Like her granddaughter Angel, she lasted about a year in the convent. (I am struck by how fortuitous my existence is as a descendant from this line—my great-grandmother and my mother both made attempts to lead celibate lives.) Her children write that the convent was “harsh”; the Mother Superior “felt that self-denial and poverty” were a necessary part of the training, and “Frances did not think much of this life.”1 Leaving behind this emotionally hostile atmosphere of self-abnegation, she returned to Chicago, lived with her aunts, and worked as a seamstress until her marriage was arranged. Nadine, her granddaughter, in an autobiography written while she herself was a novice in the Felician Order, wonders “how strange it was to be taken from the convent, where she spent a year, and marry a man she never saw before in her life.” And in this situation, she praises her grandmother for being someone “determined to make her marriage successful.”

The choices for a girl like Frances at that time were constrained by her class position. Once she left the convent, she had no education or resources to pursue an independent career. Frances’s decision to leave the convent was almost by default a decision to get married in order to establish her own household. Despite the fact that her father arranged the marriage, the marriage actually afforded her some independence, even if it did mean establishing a dependent relationship with her husband.2 In that new relationship of dependency, however, the matrifocal nature of Polish-American families gave her more power to determine her life in its frills if not its essentials—to decide how to arrange the furniture, what to grow in the garden, which curtains to buy. She became the matriarch of a household while living in a patriarchal family and society. In Frances’s case, she also gained an edge in the marriage because of her nativity as an American, and because her bloodline connected her to landowners in Poland.3 Despite the fact that it was arranged, the arrangement afforded her some power vis-à-vis her husband and her family.

Frances and Ladislaus were married on May 30, 1898, in St. Stanislaus Church in Hilliards.4 In addition to the church, Hilliards had six other buildings: a general store (which is still in operation) that also held the post office (in operation there between 1869 and 1953), a bar, a community hall, a pickle factory, a creamery, and a cheese packaging factory. Poles settled in this region in a four-by-four-mile area that straddled the townships of Dorr and Hopkins, located along 138th Avenue.5 Most of the farms in the two townships were owned by Americans of northern European descent (mostly English and German with a few Irish, Scottish, and Dutch); however, a defined Polish corridor appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, and by 1913 it was densely populated (see map 1).

Only four Polish families are identified on the plat maps of 1873, but by 1895 there were forty-six Polish farmsteads occupying almost 3,500 total acres, and by 1935 Polish immigrants and their children owned more than 8,000 acres on 104 farmsteads.6 Between 1895 and 1935 the number of farmsteads grew more quickly than the number of Polish surnames in the area, signifying that in-migration had slowed down.7 By the twentieth century, growth in the community came from within, through the retention of the second generation.

A few years after they were married, Ladislaus and Frances took over his father’s 120-acre farm.8 Polish farms in that region survived through a combination of subsistence farming, market-oriented farming (grains, milk, and cucumbers for pickling sold locally), and intermittent work in industries (the creameries, breweries, and canneries in the rural towns, and factories in Flint, Lansing, and Grand Rapids). Every farm had a large garden, the women’s domain, that provided fruits and vegetables for the family. They stored potatoes and carrots, canned apples, rhubarb, pears, and strawberries, and slaughtered pigs, chickens, and cows. They also made lard, head cheese,9 and sausage from the pork scrap.

They called themselves dairy farmers because cows provided their most regular source of income, but they had a diversified agricultural economy that was labor intensive.10 Their main cash crop was wheat, but they also grew a variety of other grains, in particular timothy hay, clover, and oats both for feed and the market. The other source of income was the pickle patch, which netted the Fifelskis some two hundred dollars annually by the 1920s, to be spent on school clothes in the fall. Pickling was a practice that Poles brought to Michigan, and growing cucumbers for market continued until the 1940s.11 The farms survived by using family labor, which worked well for a farmer like Ladislaus Fifelski, who had seven sons. Their holdings, however, were never large enough to divide among many sons, so one son inherited the farm and the others bought their own land or found work in factories.12

By midcentury, the main source of family income was no longer the farm but the factory. No sharp line, however, demarcates factory work from farm work. The farms were initially bought with wages earned in the industrial sector, and early farmers also supplemented their farm earnings with wage labor.13 Ladislaus worked in a furniture factory in Chicago before he became a dairy farmer in Hilliards; when his sons were old enough to manage the farm, he once again found work loading freight in Grand Rapids. His seven sons also straddled the shop floor and the barnyard. Some worked full-time in factories and lived in the country, others moved from factory to farm to factory, and still others worked in factories only long enough to raise the money to buy their own farms.14 Most of the farm boys in the second generation started working in nearby cities during World War I. Only one of Ladislaus’s seven sons remained a farmer, and Ladislaus’s own farmland was sold by his youngest son in 1947.15

Map 1. Development of the Polish corridor in Hilliards, Michigan, 1873–1935

. . .

A year and a day from their marriage, Frances delivered her first child, a nine-pound boy, born to this slight seventeen-year-old girl who months before the delivery still naively believed that St. Joseph delivered babies. Ladislaus informed her that the baby would come out the same way it went in.16 Over the next twenty-five years they kept going in and coming out. The second child was born the following May, the third the next year; she had all but one of their thirteen children two years apart.17 She either was pregnant or nursing a newborn for twenty-six years. (Actually, she was too weak to nurse her first child, but she did nurse the next twelve.) All of them were big babies—the smallest was nine pounds, and her last child, delivered when she was forty, was twelve pounds.

Fig. 8. Frances and Ladislaus, c. 1938

Frances had a reputation for being a “tough bird.” She cultivated a large garden, sewed and cooked for her large family, and cared for and cleaned a large house. She worked—even if she received no wages, she worked, and this fact is noted in the public and private memory banks. On the 1910 census—where the occupational category for most women was left blank or listed as “keeping house”—Frances’s occupation read “farm labor” and the census recorded that she worked fifty-two weeks of the year. But she never did “men’s” work, her son Walter defends. “She was short and kind of heavy. She was a tough old gal, I’ll tell you that. But she never worked on a farm. She never worked the barn. Never! She was a hard worker, but she never worked out in the field. Maybe like when they had to pick pickles or something like that, but outside that, to go out and pull corn or work horses, no, never. And same way with doing chores in the barn. I can never remember her ever going into the barn.” Women’s work, though strenuous and significant, was separate from the routines of men.

Frances was small, but there was nothing weak about the grandmother of the Grasinski Girls.18 Her strength was located in a set of traditional gender routines that included tending to flowers and family. Her namesake and granddaughter Frances remembers “her peony gardens all the way from the front of the house down to the road and, you know, as heavy as she was she did all the work and everything herself. Always walking up the hill, pushing the wheelbarrows, and planting her flowers, all her rose bushes and, well, that was what she was kind of known for. Besides having thirteen children.” Pictures show her standing in a faded blue print dress, full apron, and white sandals in front of her fiery red cannas. My aunt Caroline remembers that her grandmother “instilled in me my love of flowers and planting. And she used to say, ‘We don’t get in trouble. We don’t talk about anyone. We talk about trees and flowers.’ [laughs]” Her granddaughters still have offshoots of her peonies. And they all remember her laughing. Fran said, “Oh, my, she laughed a lot and so did the aunts. That’s where we get that from—Aunt Sophie, everybody laughed at the drop of a hat, Aunt Clarice, Aunt Agnes—oh, they laughed all the time. I mean, they laughed and kidded no matter what age they were. That’s where I think we get it from.”

Thin ankles, thick waists, peonies, pickled cucumbers, laughter, strength, piety, and an air of aristocracy because one time, long, long ago, someone owned some land in Poland. This is what Frances passed on to her granddaughters, the Grasinski Girls.

Helen on the West Side

Helen, the mother of the Grasinski Girls, was born in 1903 in Hilliards. She was the fourth child of Ladislaus and Frances. She married the boy down the road, Joseph Grasinski (the son of Józef Grusczynski), at St. Stanislaus Church on August 22, 1922. Joseph had the air of a landowner, and when forced to work the fields he rode the tractor wearing a fedora. Helen shared his desire to move up and away from the farm. Given the restrictions placed upon her choices (“Frances and Ladislaus would not allow them to date other than Polish Catholic, and they had to know the family”), she thought that Joe was a pretty good catch.19 Helen had more freedom than her mother (whose marriage had been arranged), but less than her daughters, who would be constrained only by religion.

Fig. 9. Helen and Joe on their wedding day, 1922

When they married, Joe Grasinski was already living in Grand Rapids, a city about twenty miles north of Hilliards. In 1920, there were over 4,200 foreign-born Poles living in Grand Rapids and almost three times as many Dutch immigrants.20 Poles and Polish Americans moved to the city because it held more promise than the farms, especially in terms of work.21 They moved into Polish neighborhoods situated near the local industries: the brickyards, the gypsum mines, and the furniture factories. Immigrants were more likely to work in these industries, especially in the lower-skilled positions that required heavy manual labor.22 The second generation of men, however, including Joe Grasinski and his brothers-in-law, more often worked as skilled laborers, in particular as machinists and toolmakers in the nascent automobile industry. Throughout the early years of their marriage Joe worked at several factories. Between 1923 and 1936 he is listed in the city directories with the following positions: machinist, filer, die maker, auto worker (which he begins in 1929), and toolmaker (from 1933).23

By 1930, the census takers counted 4,690 foreign-born Poles in the city, and twice as many in the second generation, together representing about 8 percent of the total population in Grand Rapids.24 The Polish community was dwarfed, however, by the Dutch community, which was twice as large.25 Grand Rapids was the center of Dutch life in America and of the Dutch Reformed Church (also known as the Christian Reformed Church; its adherents are called Calvinists). Calvinists followed a strict moral code that prohibited drinking, dancing, gossiping, working on Sunday, and union and Masonic membership. Their presence cast a conservative pall over Grand Rapids. Prohibition came to Grand Rapids in November 1916, six months before the rest of the nation went dry. More than 160 saloons were closed in Grand Rapids (mostly on the Polish-populated west side of town). While the Polish Catholics voted against Prohibition, against regulations on theaters and other places of entertainment, and in favor of the eight-hour workday for city employees, the Dutch Calvinists voted just the opposite.26

Though not the largest ethnic group, the Poles’ densely populated neighborhoods and Roman Catholic faith in a largely Protestant town made them a visible minority. The Dutch conservatism in Grand Rapids exaggerated the behavior of the “fun-loving” Poles, who enjoyed robust dancing and a strong drink. Sometimes their drunkenness spilled over into violence. One headline in the local newspaper in April 30, 1913, read, “Stab Six Men at Wedding, Polish Gangs Attack Guests Leaving St. Isador’s [sic] Hall, One Fatally Stabbed.”27 While both groups were known for hard work, frugality, and home ownership, the Dutch comported themselves in a more austere manner. The Dutch kept holy the Sabbath by praying and sitting quietly. The Poles celebrated the day of rest by setting up stages in Richmond Park for polka bands and bringing out kegs of beer.28 Grand Rapids historian Z. Z. Lydens writes, “Later the west side took Poland’s sons and daughters to its bosom. The Poles were Slavs, Catholic, and given to fun even on the Sabbath day. The Hollanders were Teutonic, Protestant, with a more rigid religious behaviorism. The kinship therefore was thin. . . . The children had their taunts: ‘When the angel rings the bell, Polacks, Polacks go to hell.’ The taunt was automatically reversible and as effective one way as the other.”29

It was the Poles’ religious devotion that eventually saved them from the Christian Reformers’ tongues of fire. Reflecting on their ability to build magnificent parishes, a Grand Rapids historian writes, “The Poles might live in tiny frame houses, might labor at hard dirty jobs, might be slandered as drab and no-account, but through their faith they asserted glory and found radiance for themselves. For this, the core of their life and community, they would sacrifice.”30 And they did sacrifice, saving enough money from meager wages to build three magnificent churches near the areas where they worked. Prussian Poles founded St. Adalbert’s Church in 1881 near the furniture plants on the northwest side, and the parish community became known as Wojciechowo (the St. Adalbert District).31 St. Isidore the Plowman was organized in 1897 on the northeast side of Grand Rapids near the brickyards.32 The densely populated neighborhood, referred to as Cegielnia (the Brickyard District), was composed of small, inexpensive single-family homes.33 The third Polish parish, Sacred Heart, founded in 1904, was located in a neighborhood of Polish immigrants and second-generation Polish Americans which became known as Sercowo (the Heart District).34 Reverend Ladislaus Krakowski, the organizer and first rector of Sacred Heart, was himself a second-generation Polish American who had been born in Hilliards.35

The immigrants living in Sercowo were more likely to have recently arrived from the Austrian and Russian partitions and often worked in the nearby gypsum mines.36 This community, however, became home to many economically mobile second-generation Polish Americans.37 The houses were larger and more expensive than those in Wojciechowo or Cegielnia. Many were built of brick and cement, had leaded-glass, beveled windows, large front porches, and bordered the green expanse of John Ball Park (newly developed by the architect Wencel Cukierski, superintendent of city parks from 1890 to 1908). One section near John Ball Park was even referred to as the Polish Grosse Point.38

The community grew rapidly at the beginning of the century. By 1913 there were three hundred families in the parish and twelve societies; in 1925 there were five hundred families, and most of the newcomers were second-generation Polish Americans. The number of baptisms swelled between 1915 and 1923, with an average 116 baptisms annually marking the initial growth of the parish, and then peaked again between 1947 and 1959, with an annual 125 baptisms consecrating the community’s third generation of Polish Americans.39

. . .

The grandiose twin-spired church of Sacred Heart Parish was dedicated on New Year’s Day, 1924. Joe and Helen arrived in Grand Rapids six months before the first peal of its four large bells. According to the 1923 city directory, “J. Grasinske” rented a house at 1058 Pulawski Street, two blocks from Sacred Heart Church, and Helen’s older brother, also named Joe, roomed with them.40 Their first daughter, Caroline Clarice, was born on June 1, 1923 (forty weeks and two days from the date of their wedding). The following year they moved into Wojciechowo, four blocks from St. Adalbert’s Church. Over two-thirds of the families on their block were Polish.41 In 1926, they moved again, this time a half mile west to a neighborhood of Dutch, Germans, Lithuanians, and Poles (only three of fifty families had Polish names on the street). They remained in St. Adalbert’s Parish and “Jozef Gracinski” is listed in the church directory.42 At this time, Helen’s brother Valentine boarded with them; meanwhile, Joe and Helen had two more daughters, Genevieve Irene (1925), Frances Ann (1928), and then a son, Joseph Stanislaus (1930).

On July 11, 1930, Helen F. and Joseph Stanley Grasinski took out a mortgage of $3,400 with The Industrial Company for a home in Sercowo.43 They moved their three daughters and two-month-old son into a new three-bedroom stucco house at 215 Valley Avenue, less than a hundred yards from Sacred Heart Church, and only a few doors down from Helen’s brother and his wife (who bought a lot next to her father) (see map 2).

The Grasinski house was elegant for that time and their people: it had a fireplace with a wooden mantel and ornate mirror above it, stained-glass windows, glass doorknobs on heavy wooden doors, and a solid brick porch. Caroline, the eldest daughter, describes the neighborhood:

That was a godsend because in the Depression with no money, no nothing, and we were in a beautiful neighborhood, in the park and near the church, so it was just very nice. It was Polish, pure Polish. Father Karas was the one that baptized me and then there was Father Kaminski, and Father Kozak, he was a nice priest. And I still remember all the people that lived around there. I can go right down the line. Grupas lived there, and Girsz, Bobby Girsz was a lawyer, and Snow, he was a judge, and then Czechanski and Uncle Joe and Aunt Florence and her mother, father, and her brother, sister, and on the other side of the street were Paczkowskis and Borutas and Bochanek. Every day I went with this big bag of groceries. I ran to Lewandowski’s grocery store and I remember a priest, we had an assistant pastor at that time, his name was Francis Kozak. And he always stood there with a nickel so I would buy him a cigar. [laughter] So I was always buying a cigar on top of them groceries. I was running all the time.

The ethnic homogeneity of the neighborhood produced a sense of comfort that comes from knowing one belongs, while the economic heterogeneity (the judge lived next door to the machinist, who lived next to the lawyer) stabilized the neighborhood, at least in the early years of the Depression.

Map. 2 Valley Avenue in the Sercowo neighorhood of Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1932

The older Grasinski Girls remember the time with great fondness: the access to the swings in the park, strawberry pop, Mom in the house cleaning and singing “Genevieve, Sweet Genevieve,” the young girls waiting on the porch for Dad to come home from Jarecki’s factory, daily trips to the grosernia and buczernia, neighbors who were relatives and others whom they knew by their first names.44 Most likely, Joe got his hair trimmed at Polska Balwiernia on Butterworth Street, bought coal from Stanley Gogulski, and read the Grand Rapids Press.45 Helen had Lillian Rybicki set her hair in tight rollers with egg whites and shopped downtown at Woolworth’s. The oldest Grasinski Girls, Caroline and Gene, were among the 880 students enrolled in Sacred Heart’s elementary school.46 In church they sang “Serdeczna Matko,” and on Christmas they sang, among other carols, “Dzisiaj Betlejem.”

They lived in a vibrant hybrid community that was becoming increasingly Americanized. Even when Polish Americans were listed in public documents with their Polish names, their neighbors called them by their American translations: Sniatecki was Snow, Paczkowski was Bell, and Rybicki became Fisher. While the Polish language was used in churches, schools, social clubs, and businesses, American-born Poles were more likely to speak English at home. The oldest Grasinski Girls rarely heard their parents speak Polish, and then it was only to each other and not to their children. Caroline, Gene, and Fran learned Polish in school and at mass: they learned to pray the Ojcze Nasz (Our Father) and the różaniec (rosary), and they sang “Twoja Cześć Chwała” and “Witaj Królowo Nieba.” The oldest Grasinski Girls also made their confessions in Polish well into their teens.47 It was mostly in the church that their language (and Polishness) was retained, through their participation in the religious pageantry of the holidays. They remember Pasterka (midnight mass) and the kolędy (carols), the sharing of the Christmas wafer (opłatek), the Sunday vespers during Lent chanting the Lamentations of Christ’s Passion and Death (Gorzkie Żale), the blessing of food at Easter (Święconka), and the Rezurekcja (sunrise mass of the Resurrection).

The Polish church socialized them into ethnic routines at the same time that it reinforced American values and helped them to become accepted into the larger society. The pastor of Sacred Heart, Reverend Joseph Kaminski, a second-generation Polish American addressing his ethnic parishioners in 1923, stated, “True Americanism or patriotism manifests itself in industriousness, in religious and moral conduct, in the family circle, and in ownership of a home.”48 Framed this way, praying the Ojcze Nasz helped define them as “true Americans”; as such, the ethnic institution became a springboard for their assimilation into the larger society.49

. . .

Helen never worked outside the home, but she did take in family members as boarders.50 Women’s work during that period was physical and time-consuming. Helen swept the carpets, rolled them up, and took them outside to beat them; she boiled the clothes on a wood-burning stove in the kitchen, scrubbed them on a washboard, wrung them out by hand or through a hand-operated machine, hung them out to dry, and then ironed them. She washed the curtains seasonally and cooked daily. She cleaned the wooden floors every Saturday, and the girls polished them by skating around with rags on their feet. She sewed her own and her children’s clothing by hand, using meticulous, tiny French stitches. In addition, she took care of their growing family. While living on Valley Avenue, Helen and Joe had their fifth child, Patricia Marie, in 1932.

At that time, Joe worked at Jarecki’s, a factory that made machine parts. He was soon laid off from that job and found a part-time position at Hayes Body Corporation. When Hayes Body Corporation began to feel the effects of the Depression, Joe was laid off again. Without a job, they could no longer make the mortgage payment, and on October 4, 1933 the house was turned over to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company for the sum of twenty-five dollars. As a condition to the indenture, the family was allowed to live in the house for another ten months, paying rent at market rates.

Home ownership was important for Polish families, providing respectability and helping immigrants reconstruct themselves as Americans rather than foreigners. In the 1920s, 50 percent of the homes in Grand Rapids were owner-occupied, and the Poles and the Dutch had the highest rates of ownership of all ethnic groups.51 In one study, one-half of the Polish furniture workers in Grand Rapids owned their own homes in 1910, many of them small and modest, yet burdened with mortgages at high interest rates.52 Because of heavy mortgages, foreclosure proceedings started sooner than among those with lower debt-to-value ratios. The failure of the Polish American Bank also had a ripple effect through the Polish community.53

The loss of these homes was not just a material loss but a loss to dignity. Leaving the home on Valley Avenue is something the older sisters vividly remember. Caroline said, “I remember the day we had to leave that house. I still can hear it. Mom had Joe in the green stroller and Fran sitting down on the bottom and Gene on one side, me on the other, and I still can hear the wheels on that stroller going.”

While Sercowo remained stable during the first part of the Depression (between 1930 and 1932, only five of forty-seven residents on Valley Avenue moved), 43 percent of the residents left between 1932 and 1935. Sacred Heart Parish also went through difficult times. The church, which was completed in 1924 at a cost of $250,000, was built on borrowed money. The parishioners banked on the continuation of immigration and general prosperity, but when the quota laws closed the door to immigration in the 1920s and the Depression hit, Father Kaminski had to “go door-to-door begging for funds to meet the mortgage.” Unfortunately, at that time, the church could barely raise $30 in its Sunday collection.54

The Depression hit Grand Rapids hard: at its bleakest point, one in four Grand Rapids workers was unemployed.55 The furniture factories, machine shops, and the embryonic automobile industry laid off men. Grand Rapids City Manager George Welsh, a progressive Republican, created public works projects for men, believing that “a man had a right to save his honor by working for his keep.”56 Most jobs were aimed at developing the city’s infrastructure and required manual labor; men with families were given hiring preference. Joe Grasinski, who now had six children, was given a WPA job digging ditches and laying pipes. His daughter Fran recalls, “I can remember when we were going to St. James, when I was in the first or second grade, my father worked for the WPA. He worked digging some kind of tiles or water pipes, right in front of St. James school. I can remember I’d run out on my lunch hour and he’d be there, sweated up and everything. He’d be diggin’ that hole, and I’s so proud of him, so proud, that was my dad.” He eventually found work in an automobile factory in Flint, where he commuted weekly. In 1936 he relocated to the newly opened Fisher Body Plant, a subsidiary of General Motors, just south of Grand Rapids. He started as a tool-and-die maker and worked his way up to foreman before he retired in 1958.

. . .

After they lost their house on Valley Avenue, the Grasinskis moved from house to house on the West Side, “but we never lived in crummy, crummy areas,” Fran says. “We lived on rent, but it was still always, you know, it was still nice areas.” Helen was a “meticulous” housekeeper and, even though they were poor, they dressed with style. Fran said, “We always got a dress with a pocket, and then this hanky had to be hanging out of the pocket. And our hair, there was no money for ribbons, so we had to tie it with bias tape.57 But she’d iron it out, and she’d put knots on the end.”

In 1936, during this period of bi-yearly moving, Angela Helen, their sixth child, was born. Eventually, Helen and Joe gave up on city life and moved back to Hilliards. In 1939, they bought the eighty-acre Walnut Hill Farm, the farm adjacent to her parents.58 Joe continued to work in the city, on the third shift. During the day he would help his father-in-law in the fields. They also raised chickens and had a large garden but their income came primarily from his job in the factory. The thirty-mile round trip he made daily is something all of his daughters have mentioned—every night, in the snow and in the rain, they recall, he kissed the girls goodnight and drove into town to work. He is framed in their narratives as a good father, someone into whose lap they climbed, someone who cried for them when they left home, someone who loved to sing, and drink, and enjoy a good laugh.

Fig. 10. Helen and Joe, c. 1946

Helen did not want to move back to the country. Despite the openness of the farmland, the country represented an enclosed traditional society more conservative in dress, gender roles, and lifestyles than the urban community.59 Helen and many of her sisters had an elegant manner of dressing that perhaps they inherited from their own mother, Frances, the descendant of landowners in Poland. Helen would wear wide-brimmed black hats decorated with opulent silk flowers and high-quality wool coats. Yet she was also frugal; she bought her clothes on sale, put her own roses and ribbons on her hats, wore the same coat and hat for years, and made her own soles. Her daughters remember her clothes. Caroline fondly recalls, “She had this soft wool coat and it had white fur going around the collar and going all the way down. She made a two-piece from white crepe that had big, big flowers appliquéd on it. And then she had a hat, pink crocheted silk on top of the brim, and then the under-side was all pale pink crepe and then on top were flowers, a whole bouquet all made out of ribbons.” Helen’s style was noticeable when she showed up for Sunday mass or the Saturday night chicken dinners at St. Stan’s. Joe also came to church nattily dressed, with his six daughters in high heels and silk stockings preceding him down the aisle of the small country church. The old village did not always embrace them warmly. Caroline recalls:

Coming from there [the city], it wasn’t very easy comin’ out here. We would go to church, there was no pews. They used to pay twenty-five cents for a pew and then you got your pew. And I remember comin’ into church, nobody was sittin’ but one person in that pew, and I would come into church, and kneel down, and they wouldn’t move and let me in. [laughs] Then, finally, they found one pew for us, and that was the first pew, way up in front. And all seven of us would pile in there. Then they started tellin’ us we were showing off and ooh, dear! It wasn’t very easy. I mean, well, when you come with six young girls like that, and everybody all dressed up, it wasn’t a very easy thing.

But they went, every Sunday they went. Joe sang in the choir (and later Fran and Nadine sang with him). They went to Sunday mass, to the Stations of the Cross, to midnight mass on Christmas Eve, and six o’clock Resurrection mass on Easter Sunday, when, as Nadine sighs and smiles, “this whole pew was filled with these Easter bonnets, Mom and Dad and everything.”

Caroline, the oldest, was fifteen when they moved back to Hilliards; Gene was thirteen, Fran ten, Joe eight, Patty (Nadine) six, Angel three, and Mary was born in Hilliards that same year. The Grasinski kids grew up out in the country. Caroline and her dad listened to the opera on Saturday afternoons; Genie and Fran had Halloween and Valentine Day parties; Joe and Patty fought over radio stations while doing chores in the barn; and Angel dressed up as the queen and made Mary her handmaiden. On Sunday afternoons it was Jasiu on the radio, who “played all polkas. And we’d turn that radio up and the whole house was smelling and Mother would be cooking dinner.” She would be cooking chop suey, they remember.

Fig. 11. The Grasinski Girls: Mary, Angel, Fran, Gene, Caroline, 1951

Caroline, the oldest, stayed in Hilliards. She and her husband bought the family home when Joe and Helen moved back to the city in 1954. Fran and Gene left the farm before their parents. They worked and shared an apartment in Grand Rapids until Fran married. Joe went into the army and Patty became Nadine when she entered the Felician convent. Angel finished high school out in the country and Mary finished it in town. The house in Hilliards remains the family home, and, along with the church and cemetery at St. Stan’s, a site for doing ethnicity.

Frances Ann

MY AUNT FRAN, the third Grasinski Girl, is steeped in memories and things of the past. A weekend antique dealer, she has a large house with bedrooms now empty of children and full of valuable dolls and Depression glass. She has boxes of black-and-white pictures and can produce detailed, sensuous images of her childhood: for example, discovering empty brown candy papers in her mother’s apron pocket and holding them to her nose to inhale the lingering scent of chocolate. Fran is an engaging storyteller and I sought her out at family gatherings to listen to her. She talks about people and things that came before me but still seem to matter: my great-grandmother who had thirteen children, my aunt Gene who died of a cerebral hemorrhage, my grandfather who smoked cigars, the house they lost in the Depression.

I went to Fran’s house on a Sunday afternoon and we talked for several hours in her prim, soft-colored, floral-patterned living room while her husband Albert whistled in the den. He never came into the front room, but we were never alone. Later, when I transcribed the tape, I could hear his whistling.

When we finished the first side of the ninety-minute tape she was only at age six, and she said, “That’s as far as I go.” I coaxed her through another forty-five minutes by asking her some questions about her parents, the other houses they lived in, her ethnicity. She responded to the questions and they became springboards for more storytelling. At the end of the second side of the tape, her story was up to the age of sixteen. She was flirting with sailors, hanging out with her sister Gene, taking singing lessons in Kalamazoo (she inherited her mother’s beautiful voice). And then she stopped and wouldn’t tell me any more. I tried several times to interview her again, and finally, two years later, after I sent her a small piece I had written based on the first interview, she agreed to another session, in part because I had not written enough about her being a mother. When I arrived, she had an outline I had sent in front of her and she wanted to know why there were only question marks after her name in the section on motherhood. I said it was because she had not yet told me anything about mothering. She was surprised. “We talked so long and I didn’t say anything about them?” I told her No, she didn’t say anything about getting married or the children or her antique collecting. “Those antiques are nothing,” she said, but she did want to tell me about her children and her years of work with the Boy Scouts and Campfire Girls. She also talked about her sister Gene, her involvement with the church, and the gratitude that she feels toward her mother for instilling in her a strong faith and love for Jesus.

. . .

After she finished high school, Fran worked briefly at Fannie Farmer’s candy store in downtown Grand Rapids, and when she was twenty she married Albert Hrouda, a Czech from Cleveland who graduated from Case Western Reserve University. She met Al only six times (though some visits lasted for five days) before he proposed to her. She got to know him as a pen pal while he was in the army. They were married at St. Stan’s in Hilliards and then moved to Cleveland for a few years, where she remembers riding the trolley to “the other side of town” on Wednesday nights to dance the Slovenian polka. After a few years they returned to Grand Rapids and she has been in the city ever since.

Fig. 12. Fran and Albert Hrouda on their fiftieth wedding anniversary, 1998

Her husband became a successful certified public accountant, and she raised their three children. Now they have four grandchildren whom she enjoys greatly. She doesn’t drive. From her middle-class suburban house she can walk to a small shopping center, and her husband takes her to the other places she needs to go. When she was in her forties, she started buying and selling antiques, dishes and dolls mostly. She is a devout Catholic and has always been active in the church, but even more so nowadays. Currently she organizes prayer groups and works for the pro-life movement. Every Christmas she sends me a Christmas card with a pro-life card tucked inside or a “pray the rosary” sticker on the envelope.

This is her story of the Grasinski Girls’ early years.

The Lights of the City

I was born in Grand Rapids on Tuesday, at home, we were all born at home. All the way up to Mary. We lived on Powers Avenue until I was about eight months old, and then they moved to Valley Avenue. They just rented that house on Powers, but they owned that one on Valley, and they lost it during the Depression. They needed 345 dollars and they didn’t have it. I guess they were too proud to ask anybody in the family, you know, for that, so we lost that house. That was in ’32 or ’33 and I was born in ’28.

When we moved away I was four and a half, but it seems like I remember the most of my life there. The day we were moving I can still remember, we came down the driveway and we had all our toys and everything in this red wagon. [starts to cry] I can’t talk about it. And in this wagon, piled up in this red wagon, [muffled tears] and we were pulling it to the house, to our new house, which was, oh gosh, I don’t know how many blocks away, long ways away. But we had to take it there. They had a small van, I guess to move the big furniture, but I can still remember coming out of the driveway, Caroline had the handle and Genie and I were holding all the stuff so it wouldn’t fall off the wagon. Here I’m only four years old, Genie’s seven, and Caroline is ten.

We took that wagon with those toys and we pushed it all the way to our new house. [laughter] And I’m trying to think, that was on First Street. It was probably about six blocks, maybe, that we had to go, maybe more than that. I don’t know if you want to listen to all of what I’m saying. [Me: Yeah, yeah, go ahead.] Then we went from First to Fifth. Then we moved to Third. We tried to figure out, Caroline and I, why we moved, why we moved as much as we did. It was on rent, those three times were on rent, and then they bought, out in the country. I was ten when we moved out in the country. But like she [her mother, Helen] says, Valley Avenue was her home. That’s the house that she really loved and it was really nice inside and everything. It was a stucco house and it had the three bedrooms, and it was nice. Anything we lived on rent didn’t compare with that.

I can remember from the time I was probably three to four and a half. That’s a lot. I can’t figure out how I can remember all of that, I mean, I can still feel ’em! [laughter] I can still feel all of that. I think I took everything in. There was a little porch where we used to shake the pierzyna [down quilt] out every Saturday morning, and then there was the fence in the backyard with all the hollyhocks. She used to hang up the clothes and those dresses and stuff. Genie and Caroline, they would go to school at Sacred Heart, which was just across the street, and they had these chinchilla coats, with those hats, and boy, I just couldn’t wait, ’cause when it was too small for Genie, then I got that chinchilla coat with that big chinchilla tammy, oh goodness!

Dad was working. I think he worked part of the time and then he got laid off, that was why we couldn’t keep the house. I think he was working at Jarecki’s, a factory. It was some machine parts or something like that. I used to wait for him, he would come home from work, and we had this porch, this brick porch, and there’s always the little cutout window on the porch, I don’t know what that was for, but anyways, we had it and I used to lay on the porch on my stomach and watch through that hole. As soon as I could see him coming way down the block, you know, then I’d ask my mom and she’d say, “You can go now, if you can see him you can go now.” And he had this cap on, he looked just exactly like they show them people from the Depression. [laughter] With the cap, yep, and them kinda shaggy clothes and everything. Well, we were poor.

Fig. 13. Fran, 1951

When I was six years old, I had all the baseball cards ’cause I was the one [my dad] used to take to Valley Field to baseball games on Sunday afternoon. And I can remember at that time when Joey and I were little, Mom used to dress us, we had sailor suits, him and I had look-alike sailor suits, and she used to dress us all up in them sailor suits and then we’d go walkin’ down the street. He was very proud of us. He’d meet people on the street and he’d say these are my two children. But they say he always used to pat me on the shoulder when he’d tell people and he’d say, “This one shoulda been the boy, though.” [laughter] See, Joe was very delicate. He was pale, and he wasn’t a healthy boy to begin with, but he grew up to be big and strong. I guess I was healthy. Depression or no Depression. And so, when he would go places and this is what he would say, he’d tell the guys who we were, you know, and then he’d pat me on the shoulder and say, “But this one shoulda been the boy.” And I did do a lot of things with him. I was the one that went fishing with him. I don’t know if Joe ever went fishing with him. I went fishing with him. And I used to have all the Babe Ruth baseball cards and I knew all the baseball players at that time.

It was at that time that [my mother] sold her engagement ring, because we needed money for food. Then we moved, when we got a little bit older, when he still didn’t have a job, and then he finally went to Flint, and he’d come home just for weekends, and oh, I can remember times we went to bed hungry. You know. She’d say, “Well, there’s oatmeal if you want oatmeal,” but, you know, there’s nothing in the cupboards. I can remember many days where we just got eggs and potatoes, and those big egg pancakes—they’re still my favorite. That used to be our main meal. So, we were just poor.

But that’s when we always had a Christmas tree but we didn’t always have presents. I remember the one year when we didn’t get any presents, but Joe got one present because he was the boy. [laughter] Well, you know, it didn’t make any difference to us, you know, it didn’t bother us. He got this fire engine and I remember we were all down on the floor playing with it. We got fruits and nuts and stuff like that and maybe we got a pair of stockings, something like that, but that was, uh [pause] that was a real poor Christmas.

After the Depression my dad didn’t want to be caught with that happening again. He figured that at least out in the country he could grow food, vegetables, and he could have a cow, and that’s what we did. We had a cow, one cow! [laughter] And, uh, chickens, lotta chickens. He just didn’t wanna be caught with six children with a Depression again. But see, I can remember that’s how Daddy was, that was the reason, because what are we gonna do if this happens again? At least if this happens again we can put in our potatoes and we don’t have to buy everything.

Oh, Mom didn’t want to move out there. But then, oh, we had to move and I can remember she didn’t wanta move. But she did. And here she’s moving [to Hilliards], you know, right among all her friends and relatives. This is where she lived before, the same church and everything. But she complained about it. It’s probably the only thing I remember her really complaining about. And she just didn’t like it. She didn’t want to move back out in the country. She loved the city. She’s like me, I gotta see lights. I gotta see lights and people, I gotta see them moving around. And maybe I got that from her.