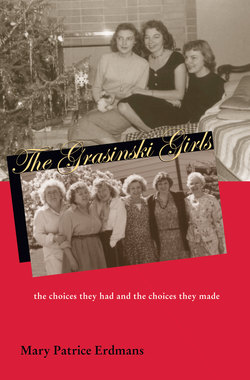

Читать книгу The Grasinski Girls - Mary Patrice Erdmans - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART I

Migrations and Generations

Fig. 6. The Grasinski Girls’ family tree

INTRODUCTION

St. Stan’s Cemetery

I WENT HOME to visit the family graves at St. Stanislaus Cemetery in Hilliards, Michigan. It was the time of the year when, more than a century earlier, the Grasinski Girls’ grandfather first stepped off the train, the time of year when the hush of dense summer green muffles the afternoon crickets and the smell of clover expands in the heat of the day. St. Stan’s connects me to the country—not the old country, but the farm fields of Hilliards.

In the cemetery, I record the names of the patriarchs and matriarchs of Hilliards: Fifelski, Jan, 1841–1916, and Maryanna, 1848–1924; Zulawski, Pawel, 1855–1939, and Krystyna, 1859–1922; Grusczynski, Joseph, 1848–1937, and Anna, 1858–1939; Fifelski, Ladislau J., 1870–1955, and Frances V., 1883–1962. I locate my bloodlines etched in stone—Fifelski, Zulawski, Grusczynski—and find my beginning in the cemetery, my connection to immigrant farmers and thick-waisted women who married young and had lots of children.

On a blustery March day in 1884, when he was fourteen years old, Ladislaus Fifelski, the grandfather of the Grasinski Girls, departed from the port of Danzig (now Gdańsk) with his parents Johann (Jan) and Maryanna.1 They immigrated to Chicago to join his uncle, who had sent the family transoceanic tickets (costing fourteen dollars for adults and seven dollars for children). His uncle, who worked for the railroad, helped his parents get jobs: his father worked on the turnstiles and his mother cleaned Pullman cars.2

The Fifelskis came from the Prussian-controlled sector of Poland.3 Poles from this sector began arriving in the 1850s, and the wave continued (roughly 450,000 in total) until the 1890s.4 They built the first Polish communities in America, often located near German settlements, as was the case with the Polish communities that later became home to the Grasinski Girls—Hilliards and Grand Rapids, Michigan.5 As a Prussian Pole, Ladislaus had a border culture composed of German and Polish strains, and generations later there is some confusion as to whether or not he was (or we are) Polish, given his “German” roots. His father’s German name (Johann) was Polonized (Jan) on his gravestone. Ladislaus spoke German and Polish, and was literate in German at the time of his arrival. He learned English at night school in Chicago, where he also learned to read and write Polish.6

Fig. 7. Gravestone in St. Stanislaus Cemetery, Hilliards, Michigan. Photo by Andrew Erdmans

Eight years after they arrived, the Fifelski family left Chicago. They traveled by train in the heat of July to the fields of southwestern Michigan and became farmers.7 They settled in Hilliards, an unincorporated village in Hopkins township, situated halfway between Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo, the two largest cities in southwestern Michigan. I once asked Valentine Fifelski why his grandfather’s family moved from Chicago to Michigan. He said it was because they had upset stomachs: “In Poland all they were living on were potatoes. And see, when they came here they were eating all this meat and it upset their stomach, so they decided to move to the country.8 They had been living in Chicago when they got a letter from a friend from the old country, and this man wrote them and tells them there is a farm for sale here.” This man was Michał Burchardt, a Kaszub (a member of a regional ethnic group in Poland) who had emigrated in 1868 from the Tuchola region north of Poznań.9 Burchardt spoke Polish, German, and English. His language skills as well as his knowledge of the area allowed him to be a cultural intermediary and real estate broker for the Polish immigrants. Walter, Ladislaus’s youngest son, said the Fifelskis came to Hilliards “mainly on account of this old Mike Burchardt. Understand, my dad learned how to speak some English, but his parents never did, and even my grandpa Zulawski never spoke English. [Burchardt] was the guy to fall back on, to look out for these immigrants.” The Fifelskis, he continued, “knew him from the old country.” They also “knew the Icieks and they knew the Klostkas,” other immigrant farmers in Hilliards who came from Poland. So Ladislaus became a farmer in Michigan because of his networks in Poland.

Ladislaus was an immigrant, but the Grasinski Girls’ grandmother, Frances Valeria Zulawski, was a native-born ethnic American.10 Born in Chicago in 1883, she was the oldest daughter of immigrants Pawel Zulawski and Krystyna Chylewska, who also came from the Prussian partition.11 Pawel is remembered as a landowner rather than a peasant, even though he emigrated because his family lost their land.12 More than one hundred fifty years and five generations later, Pawel’s grandson Walter makes sure his great-niece knows that: “My mother’s folks were landowners, they were not peasants.” Frances was also aware that her father came from land and that her husband did not. Walter said, “See, my mother [Frances] always thought she was a little higher class. My grandfather Fifelski, they were peasants, they were farm laborers [and] over there, a peasant was a peasant.” Because social networks brought them to Hilliards, their status migrated with them.

Frances’s father, Pawel, came to the United States in 1872 at the age of sixteen and worked in the steel mills in Pittsburgh. There he married another Polish immigrant. They had four children before his wife and one of their daughters died of typhoid fever. Another daughter died of sunstroke, and Pawel was left with two sons. Pawel then moved to Chicago and married Krystyna Chylewska, who bore him nine more children. Krystyna was an immigrant whose mother, Noah-like, sent her children to America in twos to escape the poverty brought on by their father’s early death. Being the youngest, Krystyna and her brother came last, in 1881. They settled in Chicago with their older siblings, and she worked as a nursemaid. When the family make reference to Krystyna they remark on her religious devotion: “She was a religious nut,” her grandson says; “[S]he was a very pious woman,” her granddaughters write; and they all mention the altar in her house.

In Chicago, Pawel and Krystyna lived above a saloon in a two-story brownstone they owned on the corner of Paulina Street and 48th Avenue in St. Joseph Parish, a Polish community in the heart of the Back of the Yards district.13 Pawel worked first as a tailor, and then his wife’s brother-in-law got him a job on the Chicago police force. He worked the night shift, drank in the morning, worked his way up to the rank of detective, and drank a lot more. He grew so fat that his wife had to tie his shoes. Under the prodding of Krystyna, they left the city and bought a farmstead in Hilliards. If Johann Fifelski left because the meat was upsetting his stomach, Pawel Zulawski left because the liquor was.

Similar to the Fifelskis and Zulawskis, secondary migration also brought Józef and Anna Grusczynski, the other grandparents of the Grasinski Girls, to Hilliards.14 Born in 1848, Józef, like Johann Fifelski, was a former Prussian soldier. He came to the United States with his wife and six brothers in the late 1870s. They emigrated to New Jersey, where the first of their eight children was born, then to Mt. Carmel, Pennsylvania, where three more children were born, then to Glenwood, Wisconsin, where the last three children were born, including Joseph Stanislaus Grusczynski, the father of the Grasinski Girls, in 1895. They finally settled in Hilliards in the early 1900s, about a mile and a half down the road from the Fifelski farm.

Anna Grusczynski has been referred to by her granddaughters as a pani, that is, a “real lady.” She had worked as a cook on a large estate in Poland, meaning she was a house servant, where “she picked up a lot of nice things,” including her mannerisms. Like Pawel, she escaped the status of peasant; as Walter says, she was “a couple steps above.” According to the Grasinski Girls, Anna Grusczynski got along well with Frances Zulawski Fifelski, most likely because they shared the manners of the manor.

These three immigrant families in Hilliards—the Fifelskis, Zulawskis, and Grusczynskis—share features with other Polish immigrant farmers in Michigan. First, they came from the Prussian partition of Poland. Second, Hilliards was not their first place of settlement in the United States but represented a secondary migration.15 Few immigrants arrived in America with the two to four thousand dollars needed to buy farms, so they worked in the steel mills in Pennsylvania or the railroads in Chicago to accumulate the necessary capital.16 One other similarity is that they all arrived with families, intending to stay permanently. Toward that end, these immigrants set about establishing more permanent roots by creating an ethnic farming community in Hilliards.

Status within the Polish farming community derived in part from Poland. When Ladislaus’s family migrated to America, their peasant identity clung to them like the smell of cow manure on a barn coat. A peasant was a peasant. But Frances’s family had been landowners, and this status carried some prestige within the Polish farming community.17 Routines, dispositions, and status get carried over oceans, over generations, and most certainly over the course of one’s own life. Because they emigrated through networks, their social class emigrated with them and was used to distinguish ranks within Polonia, the general term for the community of Poles living abroad.

Outside the ethnic community, however, Polishness was a more salient status marker. As a structural locator, the ethnic identity ranked the group vis-à-vis other groups, which in Michigan at the beginning of the twentieth century included “Yankees” (native-born Americans of northwestern European descent). Poles ranked below Yankees, and they experienced prejudice and discrimination as a result of their ethnic identity. For example, at the dedication of St. Stanislaus Church in Hilliards on October 12, 1892, the local sheriff arrested two trustees of the church on charges of violating revenue laws for selling beer at a church fair (the Toledo Brewing Company had donated fifteen barrels of beer to be sold to help finance the new building). They were tried and convicted. The local newspaper, the Saturday Globe, reported that one of the trustees and his “compatriot with the jawdislocated cognomen” were given a deferred sentence.18 His compatriot’s name was Joseph Waynski. The real jaw-dislocating cognomen, however, was that of Józef Grusczynski, who Americanized his first name to Joseph and whose son Americanized the surname to Grasinski to avoid just such derogatory statements.

Frederick Barth argues that ethnicity is important because it stratifies and structures intergroup relations, and that what is most salient is “the ethnic boundary that defines the group, not the cultural stuff that it encloses.”19 This is evident in chapter 1, where I show that when the children of these Polish immigrants moved into the city after World War I, ethnicity (coupled with religion) sorted the groups into neighborhoods and occupations. Polish Catholics were ranked below the Dutch Calvinists who were aligned with the Protestant Yankee leaders. At that time, and in that place, ethnic identity was embedded in relations of power and domination.

In chapter 2, I show that ethnic identity was less salient in the generation of the Grasinski Girls, most of whom acquired non-Polish surnames in marriage and moved into middle- and working-class non-Polish suburban neighborhoods. For them, whiteness, rather than Polishness, was the border between groups and the basis for ranking and sorting. And yet, Polishness continued into the third and fourth generation as a culture, a set of routines and values shared with family members. The Polishness of the Grasinski Girls is not articulated in class, politics, and social status, but instead is found in the dimples of a smile that reminds them of Aunt Antonia. What is important about this shared history is not the “cultural stuff” the ethnicity (as family) encloses, but the act of enclosing, of bring together, of connecting. In the private sphere, ethnicity helps the Grasinski Girls do the gendered kinship work that keeps the family together; it locates them in a concrete place and connects them to the textured faces of people they love; and it keeps present the memory of the matriarchs and patriarchs of Hilliards.20