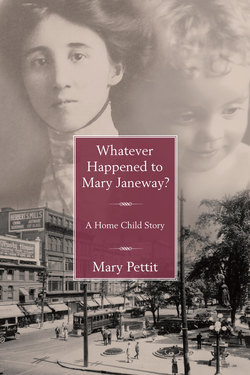

Читать книгу Whatever Happened to Mary Janeway? - Mary Pettit - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Three

ОглавлениеBack in London

“In the first decade of the twentieth century, men made up almost 90% of the labour force, and in the good years there was no scarcity of jobs.”[1]

September 1900

Mary was back in London just in time to observe the Labour Day celebrations. It rained in the morning but by noon the skies cleared and the sun came out. The rain had affected the number of spectators along the parade route, which went from Market Square downtown to Queen’s Park. But at Queen’s Park, the crowd was estimated to be about three thousand. Mary was content to catch a glimpse of the parade, as she’d only seen one before when she was living on the farm in Innerkip.

Mary learned more about Mrs. McEwen after she moved back to the city. She had a fancy goods shop and her husband was a private investigator, hence the sign on the front lawn. It was no secret that a well-to-do auntie had left them her summer home in Goderich.

The job, however, only lasted two months until the girl she’d been replacing was well enough to return. She found another general servant position and spent her days cleaning and doing laundry for a family of seven. It was similar to her job in Goderich, but without Sadie’s company and the advantage of a beach and beautiful lake.

Mary celebrated Christmas alone in her room above the kitchen. She strung popcorn and cranberries and draped it across the top of her window. Red tissue paper over the lamp and a small green candle in a jelly jar she’d picked up at the market gave her tiny room a festive look in spite of the absence of a tree and gifts. She felt fortunate in many ways. She had a job, a little money, and a roof over her head, but, more importantly, she had her independence.

January was a chilly month and everyone worked hard at keeping warm. She remembered the day that she’d stopped at the busy newsstand on the corner of Dundas and Richmond for a package of gum. People were mulling around, talking about the headlines in the London Free Press. Queen Victoria was dying. Mary remembered singing “God Save the Queen” at the orphanage and had been taught to show respect for Her Majesty, the lady whose portrait hung on the wall in the dining room. She didn’t know how to react to the latest news but sensed a general sadness in the air.

As evening shadowed London on January 22, 1901, a tired old lady slipped out of the world. Victoria, Queen of England, had ruled one-quarter of the earth, one in every five persons on the planet. One could travel around the globe secure in British law and custom, the nearest thing to a world government that man had ever known. Values were stable, business expansive, and progress was more of the new gospel. Victoria had always tried to keep things as they were. But now Victoria was gone, and with her an age.[2]

The Queen’s passing made the headlines of newspapers and magazines across the country and was the topic of conversation on every street corner. Journalists penned their thoughts and tried to do justice to the passing of a Royal figure, a Queen who had meant so much to Britain as well as other countries in the Empire. It wouldn’t be until four years later that Mary thought about Queen Victoria again. At that time her late Royal Majesty took on a more personal meaning.

Mary flitted from job to job like a bee searching for nectar. When things became intolerable in one situation, she had no choice but to look for another position. It was Mary’s lucky day when she saw Mrs. Balfour’s ad in the paper: “WANTED — AT ONCE, A GOOD GENERAL servant; in exchange for 3 meals a day, own room, $9 a month. Apply 440 Maple Street.”

She arrived at the woman’s doorstep, having walked fifteen blocks. Mary was down to her last fifty cents. Her present job was babysitting two-year old Henry, “Henry the handful.” Although he was a little monster, that wasn’t the reason she wanted to leave. Henry’s mom, a waitress who worked evenings, was often unable to pay Mary.

“I’m a little short tonight. I’ll pay you the day after tomorrow. You know I’m good for it and Henry loves you so.” Mary had stayed longer than she should have, for the little boy’s sake.

Mrs. Jenny Balfour, a short, round, plumpish lady with beautiful white hair, wiped her hands on her faded blue gingham apron and answered the gentle knock. Mary quickly inquired if the position was still open.

“Oh, I assumed someone more … mature would answer my ad,” she said.

“I’m almost seventeen and I’ve worked as a domestic since I was eight,” Mary replied. The woman ushered her into her quaint but cluttered front room. After brief introductions, she was invited to stay for morning tea. Mrs. Balfour said very little about the job and seemed more interested in chatting about her personal philosophy on life.

A small black cat appeared in the doorway. Mary’s heart skipped a beat remembering Mustard, the yellow barn cat she’d befriended on the farm. The cat meandered into the room ignoring both of them, climbed up on the windowsill, and fell asleep in the sun.

“What’s his name?” Mary asked.

“It’s Barney, but he went without one for quite a while. I found him curled up on my doorstep one cold, snowy morning last December. Felt kinda sorry for the little fella, just skin and bone. I gave him a saucer of buttermilk; he curled up by the warm stove and pretty much decided to stay. Everybody called him something different. He got Blacky, Midnight, and Patch for the white spot on his paw, which made sense, but none of them suited him. He was quiet and didn’t bother much with people, probably been a stray too long.”

“So how’d you end up with Barney?”

“I’m coming around to where I want to be,” she said, letting out a big sigh. “About the same time he arrived, I had a boarder by the name of Barney Huntley … the old codger. He wasn’t the friendliest sort, kept to himself, real quiet, but paid his rent on time. I asked him one day if he had any kin and he shook his head. So I said, ‘how would you like a cat named after you?’ It was one of the few times I’d ever seen him smile.” Mary remained silent, knowing there was more to the story.

“Poor man had a heart condition and a few months later he died, in that room right above your head,” she said, pointing upward with her index finger. Mary looked up and silently prayed that that room wasn’t going to be hers. “That’s how Barney got his name.”

“I had a cat once, his name was Mustard. It was a long time ago.”

“You said you’d worked as a domestic for a number of years.”

“Almost ten,” she said, realizing she was exaggerating slightly. “I cleaned, dusted, prepared meals, helped at sewing bees, and even baked bread and canned preserves,” she replied with confidence.

“I’m curious as to why would you’d have done all those things at such an early age.”

Mary was cautious about sharing her past and paused momentarily. “My parents passed away and I was left to fend for myself,” she said, having no intention of telling her that she’d been sent to an orphanage and become a home child. “I went to school and I can read,” she paused, realizing that that probably wouldn’t help secure the job, “and I’m a good worker,” she added. Mary thought Mrs. Balfour looked a little too old to have children at home but asked anyway.

“I have a son and a daughter.” She picked up a small pewter frame housing an old black and white photo of a young couple holding hands. She wiped the dust off with a corner of her apron and handed it to her. “My daughter Martha and her husband Malcolm live in Toronto. It’s too far for many visits but my son-in-law is in the coal business and had to go where there’s work. No children unfortunately, which means no grandchildren for me,” she said sadly putting it back on the bookshelf.

“And your son?”

She shook her head and looked out the window. “He died three years ago, three years next month, down at the docks in Hamilton Harbour. Thomas was a chainman in the foundry. They said it was a freak accident with the electric brake on an overhead crane. Lost my husband too, a long time ago. Life hasn’t always been kind, but I’ve learned to put my faith in the Almighty.”

She took a breath and continued, “That’s when I started to take in boarders. Thomas used to help out but he didn’t have a lot to spare. I’ve always done the cleaning myself but my arthritis has been acting up lately. Never had help before, kind of hate to admit I need it. Martha wants me to come and live with them. I’m putting it off as long as I can manage,” she smiled. “Would you like to see your room?”

“I’d like that, ma’am,” she replied and they headed upstairs, thankfully walking past the room that had been occupied by Barney Huntley. Mary’s room was small but not tiny, tastefully decorated in pale lilac with soft white muslin tieback curtains framing a tall, narrow window. She wondered if it had been Martha’s but didn’t dare ask, for fear that it would lead to another long-winded story.

Mary settled into her new home quickly. Whenever things were going well, she thought about her family. Her sisters were back in England, John had gone out west, and the last time she’d seen Will was the summer she turned eleven.

“Are we almost there?” she asked, looking up at her travelling companion with her soft blue eyes. The Reverend hoped and prayed that Will was Mary’s brother.

Upon their arrival shortly after ten in the morning, Will was called in from the barn. He was visibly shocked to discover his sister standing in front of him.

“Mary, is that really you?” he asked. His face went pale as he dropped his cap and ran to hug her tightly. Reverend Ward slipped out the kitchen door with a nod of his head and mouthed the words, “I’ll be back later.” The Lounsburys suggested that Will show his sister around so they headed for the barn. Once outside, Will wrapped his strong arms around Mary and clung to her.

For a minute neither Mary nor Will spoke. “Mary, I can’t believe it’s really you. Is this a dream? Let me look at you,” Will exclaimed, releasing his hold. He grabbed both of Mary’s hands and took one step backward as if to soak up every detail and put to memory what he saw. Mary was so overwhelmed, she never said a word. She couldn’t take her eyes off her brother.[3]

On November 26, 1895, a large, three-storey red-brick library building was opened at Queen’s Avenue and Wellington. Note a raised, moulded cement sign above the double-arched entrance saying Public Library and the small balcony above the entrance.

Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario.

Mary desperately wanted to find Will. It took a great deal of courage to go to the public library and ask for help. The sign perched on top of the desk said “Robert J. Blackwell, Librarian,” but a woman was standing behind the counter. Miss Rothsay, one of many assistants, was a stern little lady with short reddish-brown hair. Once you were inside “her” library, no talking was allowed — just a whisper. Miss Rothsay told her that the government had sealed the records of Canada’s home children and “she best forget about it.” Mary thought it was more likely that she couldn’t be bothered to accommodate a young girl’s request for information.

Since she was there, she decided it would be a good opportunity to borrow a book. The public didn’t have free access to the shelves prior to 1908, which meant the staff had to retrieve the books and a certain amount of interaction was necessary. Mary was intimidated by Miss Rothsay but refused to give up her favourite pastime because of a grumpy old librarian assistant.

Sometimes on her way home she’d stop to pick up a little penny candy. She couldn’t wait to lose herself in a good book while enjoying some red licorice or a few black balls. She could never completely finish one without taking it out of her mouth periodically to check the colour, and she was convinced it was a life-long habit.

It was surprisingly quiet at 440 Maple Street considering there were six boarders living in close quarters. This was probably due to the fact that Mrs. B., a nickname that Mary came up with, insisted on clean, respectable, non-smoking adults without pets even though she had Barney. Mary got used to people coming and going but was careful not to grow too attached to anyone, since the length of a boarder’s stay was never certain.

Some were easier to get along with than others. Miss Freeman, a spinster schoolteacher, had this annoying habit of correcting everyone’s grammar. Mary waited for the day that she’d make an error herself, but it never happened. When the woman was agitated, which was a great deal of the time, she’d take one of the small tortoise-shell combs from her cropped-off, tinted red hair, which she wore straight back, and scrape her scalp vigorously. As strange a habit as this was, it seemed to calm her down.

Mary preferred Mrs. Polanski, a very sweet lady who sat in the front room and would knit for hours. She always seemed so happy and content. Harvey Langdon, who everyone nicknamed Handy Harvey, thought he was both a comedian and a repairman. All his jokes began with “Did you hear about the guy who …” and even if you nodded, he’d still tell you. When Harvey fixed one thing for Mrs. B., two more were broken. Strangely enough, she never got upset with him.

Mrs. B. was a kind, caring woman with a unique sense of humour. When someone came down with a winter cold, she’d say, “If you ignore it, it would last two weeks and if you pamper it, it would last a fortnight.”[4] She had home remedies for everything from colds, catarrh, ague, ear, and toothaches, and swore by her little “cure it all” book if barley water or consommé soup didn’t solve the problem. Here is some of the advice that she followed:

To ease the pain of a toothache, clamp your teeth on a clove.

If you had an earache, drop warm oil called electric oil in the offending ear or hold a small bag of salt, which had been heated, against the ear.

To induce a good night’s sleep, warm milk with a teaspoon of honey was the answer.

A croupy cough called for a teaspoon of sugar with turpentine dripped on the sugar.

For a bad cough, eucalyptus on the sugar was the treatment as well as the inevitable mustard plaster.[5]

Mary would have to be quite ill before subjecting herself to a mustard plaster. She remembered Mrs. Chesney preparing “a plaster” for her son Jimmy who had galloping consumption. She made a paste of mustard, flour, and lukewarm water, spread it on a piece of flannelette from an old sheet, and covered it with a layer of butter muslin. It had only been on his chest ten minutes when his skin started to blister. She seemed pleased with the results, quickly removed it, and put Vaseline on the blisters. The anguish on Jimmy’s face told a different story.

Pamphlets full of medical advice based on good intentions found themselves in people’s homes. Word of mouth was powerful advertising. It wasn’t uncommon for people to see their neighbour’s names in a hand-delivered pamphlet endorsing something to promote healthy living. That’s how Mrs. B. heard about these hard black blocks called Spanish Cream for dry mouth and a hacking cough. She’d hammer them into small pieces and was convinced the pungent little nuggets had a medicinal quality when placed under the tongue. Mary was suspicious that they were nothing more than licorice.

Mrs. B. purchased liniments from the Raleigh or Watkins man at the door but refused to buy cough medicines since honey and lemon juice were just as effective and far cheaper. She also used a product derived from the deadly nightshade family called “belladonna.” She’d put a drop in each eye if she was tired and believed that it helped her to see better. In reality, all it did was dilate her pupils.

She often shared her opinions with Mary while they prepared supper. “I think people expect Dr. Phillips to make house calls when it isn’t necessary. If he charged more than fifty cents, they’d think twice about it. He’s too nice for his own good. I’ve heard that he’s made house calls to people who couldn’t pay and he’s still their doctor. That isn’t right.” Mary knew from living on the farm that many times rural folk couldn’t pay the doctor. “I remember when one of our neighbours on the farm couldn’t pay Dr. Chesney for delivering their baby … the fifth one! They gave him chickens instead. I often wondered how they decided that little Elijah was worth three chickens,” she said and then continued peeling potatoes.

“At least your neighbours gave him something,” Mrs. B. replied. “Mary, are you feeling all right? You look peaked.”

“I’m okay, just a bit of a sore throat.”

“I want you to forget about the rest of your chores today.”

“But I haven’t dusted or swept the front room.”

“A little dust or dirt won’t hurt anyone. Why a man on a galloping horse would never see it and a blind man would be glad to.” Mrs. B. insisted that she go to bed right after supper with a wet handkerchief wrapped around her neck, covered with a thick wool sock. Mary was surprised how much better she felt the next morning.