Читать книгу Whatever Happened to Mary Janeway? - Mary Pettit - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Five

ОглавлениеWoodstock

“Van Ave., as it is now commonly called, has always been considered as ‘the Avenue’ and to live on the Avenue was the final step up the social ladder of the elite of Woodstock at the turn of the century. A glance down the list of residents turns up a fair collection of doctors, lawyers, merchants, gentlemen and town and county officials. The owners of these homes engaged many servants including gardeners, parlour maids and kitchen help. Yes, it was something to live on the Avenue.”[1]

January 1904

Mary walked down Vansittart Avenue with an address carefully handwritten on Mrs. B.’s fine Wedgwood Blue stationery. She felt certain that the people living on this beautiful tree-lined street were very, very rich. She did stay with the Thompsons two months, then took a job as a parlour maid down the street, and by early May was ready to move on again. After finding it so hard to say goodbye to Mrs. B., Mary vowed she wouldn’t get that attached to people.

Her next job was as a nanny for the Heppletons for $10.50 a month plus room and board. Mr. Heppleton was a well-respected jeweller on Dundas Street. In Mary’s free time, which didn’t usually amount to much, she loved to leaf through Mrs. Heppleton’s Eaton’s catalogue. “Widely circulated across the country, the Eaton’s catalogue was referred to as ‘the wishing book’ by struggling families. You could have your goods delivered quite cheaply by freight to your nearest railroad station, or sent by mail at a cost of sixteen cents per pound. Five cents extra guaranteed safe delivery.”[2]

Mary tried to imagine herself in an Irish linen skirt worth $1.75 or a printed duck shirtwaist suit. Shirtwaists (blouses today) were one of the first widely sold affordable ready-made items ranging in price from 65¢ to $2.25. The lined cashmere waist, available in ten colours, was the most expensive, and garments costing a $1.50 or less only came in black. “I hate black,” she said under her breath, flipping the catalogue shut.

A walk to the park over on Light Street would help her forget about the beautiful clothes that she couldn’t afford. Victoria Park was a whole city-block square with big trees around the perimeter, a large cannon at one end, a few benches, and a lot of green grass. It wasn’t a particularly pretty park but it was a quiet place where she could go to read and no one could find her to do another chore.

One of the first things Mary did when she arrived in Woodstock was to find the local library. She was given directions to the corner of Perry and Dundas. When she saw no evidence of a library, she asked an elderly lady, who pointed above a drugstore. “There it is, up there, dear. I heard it was temporary but who knows for sure,” she said as she trundled off in the opposite direction. Mary spotted the door sandwiched between two storefronts and climbed the narrow staircase to find a small room with stacks of books piled everywhere. She didn’t care what it looked like, as long as she could borrow the books. To the left of the doorway was a tidy little desk with a sign on it that said Miss M. I. Robb, Librarian. Mary wondered if the librarian’s first name was the same as hers, but had no intention of asking.

After she had read the “Library Borrowing Policy” on the wall, Mary was issued a library card. She signed two books out, the limit for a first-time borrower. As Miss Robb stamped the due date on the back of each one, it reminded Mary of the time she’d gone with Mr. Jacques to pick up their mail at the rural post office. Every article of mail had to be stamped with the day’s date and either AM or PM. She’d been fascinated watching the postmaster insert a rubber pad beneath each envelope before striking it with his cancellation hammer, creating the muted thumping sound so characteristic of the post office. Mary, only eleven at the time, thought that that job would be fun.

“Your card, Miss,” a voice said, “be sure you don’t lose it.” There was no chance that would happen for fear there might be a replacement fee.

Whenever Mary was downtown she got into the habit of going to the Market Square, a few blocks past the old post office, behind the town hall. She loved to wander under the low-lying roof and wide canopies so typical of a farmer’s market and watch people barter. Woodstock had thirty-three butchers, seven on Dundas Street and twenty-six right in the daily market. When her boots needed repair, she headed to the cobbler’s on the corner of Dundas and Wilson, two stores past the tinsmith and right beside a confectioner’s. It was a bit of a walk, but his prices were the best. If she had a little money left over, she’d cross the street to Hall’s Bakery for a raisin cinnamon bun or a gooey butter tart.

The Woodstock Post Office (city hall today) with its exterior stone carving, decorative gable trim, and a bold corner tower with four clocks was an impressive sight in 1901.

The Pettit Collection.

The town hall (museum today) was built on Finkle Street in 1853 with unique semi-circular windows and a domed cupola.

The Pettit Collection.

The market (a restaurant/theatre today) had a low roof and wide canopies, typically built for an outdoor marketplace in that era.

The Pettit Collection.

On one of Mary’s outings to the park she met Ethel Kipp, who was a few years older than herself. Ethel, daughter of Orvie L. Kipp of Kipp & Schultz Butchers on Dundas Street, had a part-time job in a ladies dress shop. The two young women became good friends, and on her day off she’d meet Ethel and they’d sit in the park and chat or go window-shopping along Dundas. Sometimes Ethel would treat her to a cone or a pastry, but Mary was careful not to take advantage of her friend’s generosity too often.

Ethel knew everyone in town and would point out important people, like John White, the town’s mayor; the newly appointed postmaster, Henry J. Finkle; and Sid Coppins, owner of the local plumbing shop. “Mr. Coppins must be a very rich man. He owns an automobile,” Ethel said. Little did she know that not only did Mr. Coppins own one of the first motor cars in town but that he would own them for almost sixty consecutive years.

Later that day Mary overheard Mrs. Heppleton talking about the new hand-pumped vacuum cleaner in the window at the King Co. down on Peel Street. “According to George King, not only will it do the job far better, he’ll stand behind his invention.”

“Why would you need one, when we’ve got a girl to do the cleaning?” asked her husband.

Mary was annoyed at his remark, but at the same time curious to see this newfangled invention that would make her job easier. She invited Ethel to go along, hoping that they’d be brave enough to go inside the shop. The girls pressed their noses against the store window to get a better look.

“I wonder how it works,” Mary said.

“Why don’t we just go in and ask?”

“They’ll never believe we can afford to buy one.”

“Why?”

“Because we look poor,” Mary replied sadly, and started to walk away. Her friend followed closely at her heels.

“Well, it’s just a dumb old vacuum cleaner, who wants one anyway?”

“I do,” she replied stubbornly, “someday when I have my own place.”

Ethel shrugged her shoulders. “Let’s get a grape soda, my treat,” and she ran ahead of her down the street towards the ice-cream parlour. While they sat at the counter sipping their sodas, Ethel suggested going to the dance hall in the Market Square on Friday night. Mary was shy and reluctant to go but finally agreed to meet Ethel in the park.

She pinned her hair up and wore her newest dress, a blue percale shirtwaist that cost eighty-five cents. Mary had never been to a dance and felt awkward until she noticed a man standing over in the corner looking at her. She hadn’t been there fifteen minutes when she met her future husband, Jim Church. Mary fell in love with his dark, mysterious, grey eyes and slight hint of aloofness, and started going to the dances with Ethel every Friday night knowing Jim would be there.

“He isn’t like anyone I’ve ever known,” she said to Ethel. “He’s had lots of different jobs and his stories are interesting.”

“What sort of stories?”

“He saved a man’s life once by breaking up a fight and he’s seen waves on Lake Erie as tall as the Bank of Hamilton Building. Have you ever been to Hamilton?”

“No, the farthest I’ve been is Stratford,” she replied wistfully. Mary had been there too but never said a thing. “Anyone can make up stories. How do you know they’re true?” she asked suspiciously.

“I don’t,” Mary shrugged, “but there’s something about him … something different. You act like you’re my big sister.”

“I am three years older. Just be careful, I don’t want to see you get hurt.”

Mary started seeing Jim more often. They took evening strolls along Light Street, walks in the park, or wandered down Dundas. Mary loved going downtown at night when possible, usually a couple of nights a week when Mrs. Heppleton didn’t need her. People hurried down the street to the Market Square while horses, tied to steel-wrapped wooden hydro poles, waited patiently in front of the Opera House (now Capitol Theatre). The new electric streetlights cast a warm, romantic glow on the young couple walking hand in hand, occasionally stopping to glance in a shop window.

If Mary admired a pair of wool gloves or a scarf, Jim would insist on buying them. She knew that she shouldn’t accept gifts, but store-bought things were so beautiful and sometimes the temptation was too great to resist. Her petal-pink cashmere scarf was one of those gifts. Each time she wore it, she remembered the night that Jim had bought it. He’d wrapped it around her neck, then turned to the salesclerk and said, “Don’t bother putting it in a box, my favourite girl will wear it home.”

Sometimes they sat in Harvey Pendleton’s restaurant sipping cold sodas or they headed to Long & Co. for a homemade ice-cream cone. Occasionally, Jim would take her to the theatre. The shows lasted about an hour and cost five cents, the price of a cigar. On Saturday nights, weather permitting, a travelling salesman set up his stall in the northwest corner of the town hall square.

“Let’s head over to the square and see if doc’s out tonight,” Jim would say, grabbing her hand.

Woodstock was fortunate in having a Pitchman in permanent residence who saved many from an early grave. He was a little man with a scraggly beard and wore square lenses in his spectacles. Dr. Kinsella, better known as “doc,” would stand on a soap box and expound the wonders of his products. The Doc was of Irish extraction and was possessed with a knack of delivering an endless spiel of Irish wit, while educating the crowd on the wonders of Dr. Kinsella’s Elixir of Life Compound and Dr. Kinsella’s Corn Cure.[3]

It didn’t take long before Doc would be well into his “platform of promises” as if he was a messenger sent from God. With his hands outstretched, he claimed that his elixir of life compound, a concoction of herbs that tasted like root beer, could cure anything if taken regularly. (Doc had a ready audience until a law, passed five years later, prevented him from selling “his wares” on the street.) If the weather was bad and he didn’t show up, Mary and Jim could always count on a show over at the Perry Street fire hall. The bell rang at 9:00 p.m. sharp, the horses came out of their stalls, raced around the premises, backed themselves into their places, and waited to be harnessed by the firemen who slid down the pole. Any other time the tower bell in the fire hall rang, it signified fires, curfews, or lost children.

Occasionally they went to Fairmont Park for a picnic. Mary would buy nippy old cheese, an apple, a pear, and even splurge on white-flour buns at Poole & Co., a family-run grocery store. Jim would meet her at the corner of Dundas and Vansittart, take the picnic basket from her, and they’d grab a ride on Estelle, the streetcar.

The youth of the day considered the trip down Dundas St. hill a source of entertainment as it was always a question, “Would Estelle make the curve?” Just in case she would make the curve at Mill and Dundas some brave young buck would run up behind the car and pull the trolley off the overhead line and leave Estelle at the mercy of the foot brakes, which required sand to help stop her progress. As a result she quite frequently left the rail. There was always the problem of climbing the hill on the return trip. On different occasions passengers had been asked to disembark and walk up the hill in order for Estelle to make the grade.[4]

On their first trip out of town Jim pointed out his boarding house and the Canadian Furniture Manufacturing Company, the factory where he worked. It took up twenty-five acres along the river. After the streetcar crossed the tracks, it turned on to Park Row, heading for Ingersoll Road and finally Fairmont Park. Estelle went as far as Ingersoll, stopping en route at Beachville, but most folks got off at the park. Band concerts and weekly dances were held in the pavilion built in a grove of trees and a small theatrical stock company put on three performances a week in July and August.

The more time Mary spent with Jim, the less she saw of Ethel. One afternoon the girls decided to meet downtown for a soda. Ethel started in with her usual concerns. “What do you really know about him? Does he ever talk about his family?”

“I know his birthday is March 18th and he’s twenty-one. He’s from Bright, which is near Innerkip where I was sent to …” she stopped, remembering that she’d never told Ethel about being a home child and working as a servant, “where I lived as a child.”

“That’s it, that’s all you know about him.”

“He said he’d had a sister named Minnie and some cousins that live in Hamilton.”

“What happened to his sister?”

“He pushed her down the well one day after they’d had a little disagreement,” she said sarcastically. The look on Ethel’s face made Mary feel badly. “She died from acute appendicitis last year just before Christmas. Jim had already left home and was living in a boarding house on Dundas Street. He’s still there.”

“You’ve been to his room?” she asked, in shock.

“Of course not. All I did was walk past,” she replied innocently.

Ethel laughed. “So what else do you know about the man who’s stolen your heart?”

Mary’s face was flushed as she continued to defend Jim. “He use to work for Bain Wagon Company and now he’s at the Canada Furniture Manufacturing Company over by the river.”

“That’s Mill Race Creek you’re talking about. What’s he do?”

“He’s a trucker, whatever that means.”

“It means he moves furniture around.”

“He said it was temporary until he finds work painting,” Mary let out a big sigh. She had no intention of telling her friend about his dream to have his own decorating business someday or that some of his money had been won playing cards.

“He hasn’t said much about himself,” Ethel persisted.

“I think he’s a private person and I’m not going to pry. He doesn’t ask me personal questions either.”

“You mean he doesn’t know that your parents died from typhoid fever,” she paused. “And you and your brothers and sisters were sent to live with different relatives.”

Mary shrugged. “Of course he knows. I told him what I told you.” She didn’t like making things up, but justified it if it meant hiding the fact that she’d been a home child. What harm could come from pretending to be related to the Jacques instead of being their domestic servant? At least her last comment to Ethel was the truth. She had told Jim exactly what she’d told her. “Why can’t you just be happy for me?”

“I am, but I can’t help but worry a little.”

Mary could not remember a time when she’d been happier. As May turned into June and the cherry blossom trees came out in full, she fell deeper in love. She was turning twenty that summer and was anxious to get married. She’d finally found someone who cared for her and she wasn’t about to let him slip away.

One hot sultry Friday evening in early June, they rented a canoe and paddled down the Thames. Jim found an isolated cove and suggested they get out and sit on the riverbank. He took a flask of whisky out of his pocket. Mary sensed he had something on his mind.

“I’ve met a lot of girls but none that mean as much to me as you do,” he said softly. He stroked her hair and kissed her, like he’d done so many times in the past. One unruly lock of dark hair kept falling over her left eye. Her heart raced. Is this the moment that she had waited for, the moment most young girls dream about for years? Was he going to ask her to marry him?

“I love you Mary,” he paused. “I want you to be mine.”

“It’s all I’ve ever wanted,” she replied without hesitation. He started to unbutton her shirtwaist. “What are you doing?” She screamed and splayed her fingers across her chest.

“You said it’s what you wanted.”

“I didn’t say that at all. I said I wanted to be yours … your wife is what I meant.”

“Wife! Who said anything about getting married? I’m talking about … you know, becoming closer.”

“You mean …” she stopped mid-sentence. Mary couldn’t bring herself to say the words. She was shocked. Ethel had been right. She jumped up and ran to the canoe. “Take me home, I’ve nothing more to say to you.”

Jim paddled back to the boathouse, returned the canoe, and without a word spoken they headed back into town on the streetcar. As they approached her street she said, “I never want to see you again,” ran up the steps, let herself in, and slammed the door. She ended up confiding in Ethel, who was very sympathetic. Her friend honestly believed that she’d been spared inevitable heartache down the road.

Mary turned twenty finding little to celebrate. Her job would end in September since Matthew was starting school and a live-in nanny was no longer needed. She read the signs posted in shop windows looking for help but most wanted restaurant or office experience and didn’t provide room and board. What a servant girl knew best was babysitting, cooking, and cleaning.

Ethel finally talked her into going back to the dance hall again. It was the last weekend of the summer and an exceptionally humid evening. She’d only been there a few minutes when she felt a hand tap her on the shoulder. Mary, taken by surprise turned quickly toward the voice. “Will you dance with me?” Jim asked with that innocent boyish grin, the one that she’d never been able to resist in the past.

She shook her head and whispered, “No, it’s over. Please leave me alone.”

“Just one dance for old times’ sake. You won’t regret it Mary.” She hesitated long enough for him to continue. “One dance, that’s all I’m asking.”

“Then you’ll go away?”

“If you still want me to, I’ll go.” He took her arm and they moved out on the dance floor. The musicians were playing “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” a well-known tune that’d been around since the year she was born. “I’ve missed you so much,” he said softly in her ear. “I can’t tell you how much. I made a mistake, a terrible mistake. I should have known you weren’t that kind of girl.”

The air was stifling and she felt short of breath. Voices around her, intermingled with young girls’ laughter, seemed to be getting louder in order to be heard over the music. The smoke from men’s cigarettes curled up toward the ceiling in spirals making Mary light-headed and confused.

“I have something to show you,” he said, taking her by the hand. They left the dance hall and headed down the street to the park. It was quiet there, almost serene. It would have made the perfect photograph, a young couple sitting in the dimly lit park, framed by large stately trees moving slightly in the wind like the fringe on a winter scarf. They were oblivious to the sound of the tower bell ringing in the fire hall. Was a fire out of control, a child lost or was it just a reminder of a curfew?

For a moment Jim held her hand and then he reached into his coat pocket. “I’ve been carrying this around for over a month, hoping to see you.” He held up a small box. “I want you to be my wife. I don’t want to live without you anymore.” Mary looked down at the gold ring with a modest, pear shaped bluish-violet stone. She was speechless. “If you still want me to go away, I will,” he said quietly.

“I never want you to leave me … I never did.” Tears ran down her face as he quietly slipped the amethyst on her shaky finger and wrapped his arms around her. Mary gave Mrs. Heppleton two weeks’ notice and happily quit her job. She sent a note to her sisters in England, glad that she’d hung on to Carrie’s last letter, and hoped they hadn’t moved in the past four years.

This contemporary photo of the courthouse still boasts a massive building of sandstone with a complex roofline. The building directly behind was the county jail, which houses the Oxford County Board of Health today.

Courtesy of Rowena Lunn, Caroline Janeway’s granddaughter.

Mary had dreamed about her wedding day and knew exactly what she wanted. For her “something old” she clipped her ivory-tusk comb in her hair. She chose sateen in a creamy, rich ecru fabric at John White & Co., and along with a picture she’d snipped out of the Eaton’s catalogue, went to Elizabeth Farrington the dressmaker over on Wellington Street. She borrowed Ethel’s timepiece broche and found a dainty linen hanky edged in cornflower-blue embroidery to tuck into her sleeve.

Since Jim already owned a dark suit that he’d bought a year ago for Minnie’s funeral, he went to Amos Harwood, a well-known boot and shoemaker to have a genuine leather pair of boots custom made. As soon as Joseph A. Copps, the local barber, opened his shop the morning of their wedding, Jim got a haircut, a shave, and a cigar, and he was ready to get married.

Mary studied herself in the mirror. She’d been born in a leap year and hoped that getting married in one was a good omen. She brushed a lock of hair out of her eyes, hair that had darkened over the years. A tiny silver pair of pince-nez gave her eyes more distinction; perhaps she was realizing her own maturity. She took off her amethyst ring, believing that once a wedding band was placed on her finger, it should never be removed.

They exchanged their vows at the courthouse on Hunter Street. Mary had walked past the huge stately building many times. She’d never noticed the monkey heads hidden among the capitals of the red marble pillars at the two front entrances or stepped inside to see the ornate interior cast-iron stairways until the day she got married. And she didn’t notice them that day either.

At eleven o’clock in the morning on Wednesday, October 5, 1904, with more than a hint of fall in the air, Mary Janeway became Mrs. James Church. F.W. Hollinrake officiated, Ethel was her maid-of-honour, and Harold Teetzel, one of Jim’s co-workers at the Canada Furniture Manufacturing Company, was his best man. It was a civil ceremony that lasted fifteen minutes — the happiest fifteen minutes of Mary’s life.

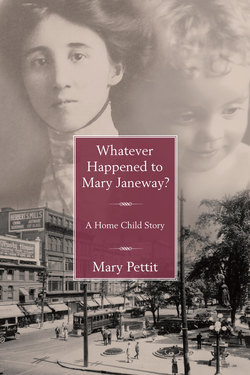

Mary Janeway looked elegant on her wedding day in a laced-trimmed shirtwaist with pouched sleeves, boned-standing collar, and a skillfully arranged pleated skirt just clearing the floor.

The Pettit Collection.