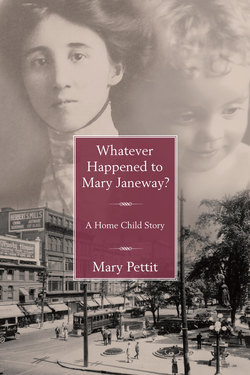

Читать книгу Whatever Happened to Mary Janeway? - Mary Pettit - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Six

ОглавлениеHamilton

“In 1903 the Hamilton Automobile Club was founded, the first such club in Canada. Yet the impact of this technological revolution was slow to develop, largely because of the lack of adequate roads. Up to 1914, motor vehicles were curiosities or luxuries more than essential components of the transportation system.”[1]

October 1904

Three days after they got married, the newlyweds headed for Hamilton. Jim had worked there before and was optimistic he’d find something. Mary knew very little about Hamilton except its nickname, the “lunch pail town.” She soon learned how the city that she’d be calling home forever got this name.

Jim grabbed a Hamilton Spectator, the newspaper that everyone called the “Spec.” It was a balmy 62 degrees at noon according to the thermometer outside Parke’s drugstore. He looked up his cousins Walter and Arnold Church, two bachelor brothers who lived downtown, so they’d have somewhere to stay while they looked for a place to live.

Jim was anxious to try out the incline railway, a newfangled man-made contraption that scaled the side of the mountain. Two sets of tracks ran side by side up the face of the mountain and a horizontal platform was attached to each set of tracks. At one time there’d been a toll road up John Street, but later James Jolley built what came to be known as the “Jolley Cut” and donated the road to the city with the stipulation that there be no tolls. However, horses had great difficulty climbing the steep mountain and the first incline railway was built on James Street in 1892.

Mary and Jim arrived just in time to watch a platform descend and empty its cargo, at least twenty people and several bicycles. Jim knew that the James Street incline was unique because the cars were powered by steam engines instead of balancing each other by cables. Technology that used horsepower fascinated him.

“Mary, we’ve got to try this.”

“There’s a charge,” she replied, squinting in the sunlight as she read the sign on the hut. “It’s two cents a trip, school children a penny. Look over there,” she pointed. “There’s steps. We could walk up, save our money, and get some exercise.”

“It’s not the same, besides I’ve had all the exercise I need today and we still have to walk back,” he thumbed in the direction they’d come.

Mary’s eyes followed the incline as it slowly edged its way to the top. “It’s looks so steep. How do you know it’s safe?”

“You’re afraid to go.”

“No, I’m not. We just don’t need to be spending money unnecessarily.”

“Tell you what we’re going to do, my pet.” He took her by the hand, swinging it in time with his stride as he headed down the street. “We’ll wait for my first pay,” he turned back. “We’ll be back, very soon.”

Within a week they found a little frame bungalow on West Avenue, wedged between two larger ones. By today’s standards the house lacked “curb appeal,” but Mary fell in love with it. She knew how to “make do or do without.” All it needed was some white lace curtains, window boxes, and a couple of red geraniums.

In 1904, Mary’s house at 100 West Avenue North was considered to be the east end of the city. It was a modest bungalow (aluminium-sided today) conveniently located close to the Barton streetcar line and the City Hospital.

The Pettit Collection.

Shortly after moving to Hamilton, Mary ran into George and Dan Mundy, cousins of the Jacques family where she’d been a domestic servant for those eight long years. While she was most interested in hearing about young Daniel since he’d been the nicest to her when she lived on the farm, she discovered that Daniel’s sister Annie and her husband Elias Zinkan had moved to Drumbo, about eight miles from the Jacques homestead. While Mary was still afraid of reprisal for having run away from the farm, she was lonely and decided to write her. Annie wrote back, which told her that the past had been forgotten, and the girls began to correspond.

Jim found work at the American Can Company, close to home. He walked down Barton Street, three blocks to Emerald, and down to Shaw. When the weather was frigid, he jumped on the streetcar. Passengers were kept toasty warm by sitting close to the stove that was being stoked by the conductor.

“The pay isn’t great but it’ll do for now.”

“I can find something too you know,” Mary replied.

“No wife of mine is going out to work. That’s my job!” Jim wasn’t alone in his thinking. “A woman’s real place, it was almost universally agreed, was ‘in the home.’ A working husband who permitted his wife to work was open to criticism for ‘not wearing the pants in his family.’”[2]

After Jim got his first pay, Mary bought a couple of yards of white cotton voile to make curtains and some red gingham for her kitchen table. Someday she hoped to have an electric sewing machine, but her eight dollar second-hand treadle would do a nice job. And it wasn’t long before the lady next door befriended her. Mrs. Tolten, a widow with time on her hands, was looking for a friend. It was nice to have someone to talk to or invite over for afternoon tea, but the elderly lady was no substitute for Ethel.

On Friday night Jim came home from work in good spirits. “Unless it’s raining Sunday morning, my pet, you and I have a date,” he paused, “with the incline.” He got up from the table and headed to the porch to light up a Player’s while Mary tidied up the kitchen.

Two days later the sun was streaming in their bedroom window. Jim woke up early, like a young child on Christmas morning. He was anxious to try out the incline. Mary, on the other hand, was dreading it. They grabbed a streetcar at the James and Gore turn-back that ran south on James Street to the base of the escarpment. Streetcars had been running on Sunday for ten years since it was no longer considered a violation of the Lord’s Day Act.

“Look at that,” Jim said. “It must have known we were coming.” The strange metal thing was descending almost filled to capacity with passengers plus a horse and wagon loaded with produce. They stood patiently in a small queue at the foot of the mountain. Jim was impressed with how it handled such a steep grade with a heavy load, but he’d heard of people being afraid to take the incline and wasn’t surprised at his wife’s reluctance.

As people got off, they walked past a small hut where an attendant collected the fare. It saved having a second one at the top. Once it was empty, Jim and Mary along with about a dozen others passed by the same hut and paid their fare. Mary was thankful there were no large wagons waiting to get on the adjoining platform attached to the narrow covered passenger car. She felt that it would be less of a risk without all that additional weight.

The incline railway (circa 1910) enabled Hamiltonians to travel from the city to the mountain. The incline became obsolete by 1931 largely because of the popularity of the automobile.

Hamilton Public Library, Local History and Archives.

People filed into the enclosure but didn’t bother sitting down, since the trip to the top didn’t take long. Everyone around her seemed so complacent and acted as if it was no different than taking a streetcar or train. Mary started to relax as it began to climb. She saw things from a different perspective for the first time in her life. The panoramic view was breathtaking and she soon forgot about her fear.

“There’s the hospital,” Jim pointed straight down, “the one you thought looked so big. What’d you think now?” She smiled.

“Can you see the tall building?” he asked as Mary squinted in the sun. “The one with the clock and further down the bay?” She followed his finger. “They’ll soon be ice fishing, curling, and skating on it. Ever gone skating?” She shook her head. As a child she remembered watching kids strap blades to their shoes and skate on Mr. Allenby’s pond but she didn’t own any.

“I can’t believe how tiny everything looks, even the horses and wagons. The people look like little ants running around,” she said. “What are those bare spots, there and there?”

“Those are parks, Hamilton has lots of them. There’s Lansdowne Park at the bottom of Wentworth Street, Sherman’s Inlet, and Huckleberry Point.”

“Lots of railway tracks too.”

“Yeah. The TH&B will take you as far as Toronto or Buffalo.” He put his hands on her shoulders and turned her around. “And those tracks go to the beach strip. See those tracks way over there?” She nodded. “They’re for the radials. They’ll take you to Beamsville, Dundas, Brantford,” pointing in different directions as he spoke, “and even as far as Oakville.”

It only took several minutes to reach the top. They found a bench in a park-like area and sat down just long enough for Jim to have a smoke. “I feel like I’m on top of the world,” Mary said, linking her arm through his.

They walked along the mountain brow, enjoying the tranquillity and beautiful wooded areas. By noon they were getting hungry. Mary regretted not bringing a picnic basket. They took one last look at the view before getting back on the incline to head down the mountain.

“I take it you changed your mind about the incline. Did you get your two cents worth?”

“And then some,” she replied.

Life slipped into a quiet, comfortable routine. Mary made friends with two ladies down the street when they were out shovelling their front walk. Viola and Affie Berezowski had immigrated to Canada from Poland as youngsters with their family. They were close to each other, having lost both parents to typhoid fever a few years earlier. Affie was a seamstress and worked out of their home. Viola, who went by the name Vi, had a part-time job in the church office.

Neither had married, but Affie, who was thirty-one, had had a serious relationship with a fellow from out east. He’d come to Ontario to work on construction and install power lines for the hydro company but once the job was gone, so was he. It was obvious that she’d resigned herself to spinsterhood like her sister.

Mary soon learned that the girls were very different. Vi had a knack for “stirring the pot” and Affie was the peacemaker. Little things like hanging the clothes out or folding the laundry could turn Vi into a fit of anger but it was usually short-lived. Although only one year older, Affie seemed far more mature. Mary preferred her company but enjoyed chatting with both over a pot of tea.

Hamilton was an interesting city. The brightly painted electric streetcars with their two-man crew smartly dressed in their HSR uniforms were an impressive sight. Mary usually walked downtown and rode home with her parcels. Saving the nickel streetcar fare meant that she slowly accumulated enough to buy a pearl necklace, a pair of stockings, or a glass candy dish.

She liked shopping at the Arcade, a department store on James Street that sold groceries as well as meat in the basement. She was most familiar with the bargain basement merchandise. A uniformed, gloved operator manned the elevator and salesclerks wore black, brown, or grey since bright colours weren’t considered to be proper attire. Customers wore the same basic colours, usually accompanied by hats and gloves.

Stanley Mills, another department store, was on King just east of James Street. It had lovely wide aisles and beautiful things displayed in glass showcases. One spring Mary found the prettiest straw hat there with pale pink artificial flowers on its big, floppy brim. She wore it with pride to church on Easter Sunday for many years. Young children loved this store, especially the enchanting Toyland around Christmas.

Woolworth’s, four stores down from Stanley Mills, was just as popular. Seemingly, many years earlier in a Woolworth Store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the first purchase made had been a five-cent fire shovel, which was why the store came to be known as the “five and dime.” Advertisements of the time tell of “lots of bargains and lots of products — from toilet paper to cream pies to parakeets.”[3] They established fixed prices at a time when bartering was commonplace. It was one of the first stores Mary had ever been in that had their merchandise on the counters for customers to handle. Woolworth’s was renowned for its great lunch counter and her favourite meal was the hot creamy chicken on a patty shell.

Mary was impressed with the number of services available to city folks. There were home deliveries for milk, bread, ice, and fish. Her milkman, Pat O’Neill, worked for the Hamilton Pure Milk Company. Since opening its plant two-and-a-half years earlier on John Street North, it had earned a good reputation for producing sterilized, pasteurized milk at a time when unsafe milk was a concern. Customers were no longer satisfied to have farmers ladle milk out of large cans into receptacles left outside their doors. The company organized its delivery routes so efficiently that they eliminated a hundred milk wagons, proving that twenty-five could deliver milk anywhere in the city early in the morning. Pat knew exactly what Mary wanted by the number of washed milk bottles she left out. If she wanted something extra like butter, cream, or ice cream, she left a note with the money in her milk box. Cottage cheese was only available on Wednesday and Saturday.

Every so often Mary would place an order with the Canada Bread Company, known for its good quality bread, oatmeal raisin cookies, butter tarts, and cinnamon squares. But most of the time she baked her own since it was cheaper.

Hamiltonians enjoyed bread delivery right to their front door, just one of the many conveniences offered to folks living in the city. Aubrey Hunt is holding the first horse’s bridle and Horace Hunt the third horse’s bridle.

Courtesy of Ross Hunt.

It was common for fuel companies to deliver coal in the winter and ice in the summer. Competition for ice storage was keen since it was only gathered and stored once a year. Several companies stored the “cold stuff” that became invaluable in the warmer months. Every February the farmers went out on the frozen bay to cut blocks of ice with a crosscut saw and float them up onto ramps. Sometimes a team of horses and the bobsleigh would go through the ice and the entire team would be lost. The ice blocks, about four feet long and three-to-four feet deep were taken by sleigh to one of the ice and fuel companies and stored in buildings insulated with sawdust walls. They were stacked eight rows deep with sawdust sandwiched six to eight inches thick between each layer of ice. There was enough ice harvested in four weeks to accommodate the needs of Hamiltonians for that year.

Elijah Dunbar, a friendly man with a Scottish accent, was Mary’s ice and coalman. Like the milkman, he was considered family. He picked up his load from the Abso Pure Ice Company down on Bristol Street early in the morning. By the time he got there, the ice blocks had already been removed from the building, gone through the scoring machine, and were waiting on the platform. After loading his wagon, he was on his way. Elijah sold tickets, charging half a penny for a pound. Ice was sold in blocks of twenty-five, fifty, seventy-five, or one hundred pounds and delivered three times a week. Mary would place a card in her front window to indicate the size of ice block she needed. Her card was usually on the “50” side, unlike some of the rich folks in the west end who had larger iceboxes.

The neighbour kids loved to watch Elijah wield his ice pick. Sometimes he’d chip a little ice off the block and give it to them as a treat. Then he’d go on about his business, carrying the block through the back door into Mary’s kitchen. Her pine icebox, fortified with a metal liner to act as an insulator, had a pan underneath to catch the water. Still, the ice would only last two days.

Mary found it much simpler to keep food cold in the wintertime in the three-sided metal box that hung outside her kitchen window. All she had to do was open the window to get the food that Mother Nature was protecting. When refrigerators became popular in the early 1930s, people gladly got rid of their iceboxes.

Hamilton had three daily newspapers, the Spectator, the Times, and the Herald, as well as postal delivery twice a day, six days a week. The “pillar box red” mailboxes, which some called “royal red,” were a common sight on street corners. Tom Patton, Mary’s talkative postman, informed her that mail had been coming to the doors of Hamiltonians since 1875.