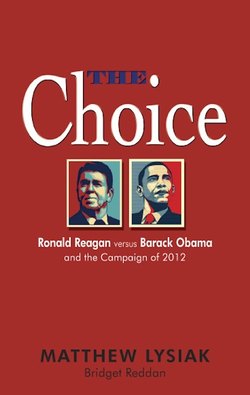

Читать книгу The Choice: Ronald Reagan Versus Barack Obama and the Campaign of 2012 - Matthew Ph.D Lysiak - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

September 4, 2008

It was supposed to be the moment that marked the end of the irrepressible Ronald Reagan.

As Senator John McCain stood on the stage of the Energy Center in St. Paul, Minnesota, ready to accept the Republican Party’s nomination for President of the United States, many in the crowd of GOP faithfuls wondered if this would be the last time they would lay eyes on Reagan. It was an inescapable fact—Father Time was catching up to him. Having lost the Republican primary twice before, Reagan would be sixty-nine years old by the 2012 election. Many in the media already had California’s former governor dead and buried. The Drudge Report had run a typical headline, “Into the Sunset,” below a picture of Reagan galloping off on horseback. Even the right-leaning Wall Street Journal was adding to the discussion, editorializing that Reagan was finished, too old to consider another run.

Reagan’s loss to McCain had demoralized the Conservative base. After having lost the opportunity to retake the Republican Party for the first time since 1964 by only a few dozen votes, they were now forced to suffer the ultimate indignity—a front row seat to a John McCain victory lap:

“I’m going to fight for my cause every day as your president,” McCain said. “I’m going to fight to make sure every American has every reason to thank God, as I thank him, that I’m an American, a proud citizen of the greatest country on Earth. And with hard work—with hard work, strong faith, and a little courage, great things are always within our reach.

“Fight for what’s right for our country. Fight for the ideals and character of a free people,” McCain roared. “Fight! Fight! Fight!” he screamed, mechanically pounding his fist on the podium.

It was the best speech of McCain’s career and he knew it, but throughout the cheers, the soft downpour of red, white, and blue confetti, and the miles and miles of bunting, bitterness clung to the air. After all, it was Reagan, not McCain, who had won the popular vote, 50.7% to 49.3%. The results were an open sore that McCain couldn’t resist scratching.

“Look around. Most of those grinning faces would rather stick their pitchforks in my back than see me become president,” McCain muttered through a terse smile as his wife Cindy greeted him on stage.

After one of the tightest nomination battles in history, McCain had barely managed to run the clock out on Reagan’s furious fourth quarter rally, winning by a meager fifty-seven delegates. Had the battle gone to a second balloting, Reagan would have likely won the GOP nomination, as delegates in states like North Carolina and Kentucky would have been able to vote for Reagan, who was their true preference.

In McCain, the GOP had put forward the centrist, moderate candidate long desired by the Republican establishment, fearing that a Reagan victory would have alienated the Independent and Moderate vote, thus plummeting Republicans back into the post-Nixon dark ages of everlasting minority status. A New York Times editorial captured the party leaders’ mood:

There is one way, it seems to us, that the Republicans could dig their own political grave for 2008 as surely as anything can be done in American politics. That is by capitulating to the far right of the party that forms the core support of Governor Reagan in his quest for the nomination. To put it in the crudest political terms, the far right of the GOP has no place to go; yet the nomination of Governor Reagan to the presidency (or, for that matter, the vice-presidency on a McCain ticket) would surely alienate the most important centrist and liberal segments of the Republican Party, without whose support it could not conceivably achieve national success.

The grueling fight for the hearts and minds of the Republican Party had been as divisive as any in recent memory, splitting the party into two warring factions. McCain and Reagan had publicly laughed off all talk of party dissension, but behind the scenes McCain, “The Maverick,” was furiously scrambling to win over the party’s right wing.

“This is cannibalism,” he had fumed to staffers, following an especially contentious interview on The Laura Ingraham Show after being pressed on the immigration bill he had co-sponsored with Ted Kennedy.

If it wasn’t Laura Ingraham, it was Rush Limbaugh. If it wasn’t Sean Hannity, it was Matt Drudge. To John McCain, it seemed like there was always a conservative boogieman plotting to keep his campaign from honestly connecting with the party’s right flank. It was not just Fox News or talk radio that raised McCain’s ire. Over the course of the campaign he had developed a deeply personal animosity for Reagan, believing that that during the campaign Reagan had intentionally distorted McCain’s record, especially on immigration.

“It’s dishonest and he knows it. I’m not for amnesty now. I’ve never been for amnesty,” McCain had vented to Juan Williams in a National Public Radio interview on August 4. “But what can we expect? My friend from California is a paid actor and knows how to play a role.”

Further escalating tensions, two days before the convention a group of economic conservatives, spearheaded by Reagan, had managed to insert language into the party platform that direct slapped at McCain’s support of big-government bailouts: “We do not support government bailouts of private institutions… Government interference in the markets exacerbates problems in the marketplace and causes the free market to take longer to correct itself.”

Asked about the language, instead of backing down, Reagan had decided to take yet another swipe at McCain and President Bush. “I hope we once again have reminded people that man is not free unless government is limited. There’s a clear cause and effect here that is as neat and predictable as the law of physics: as government expands, liberty contracts,” Reagan had told supports outside the convention hall.

McCain was still fuming. He believed Reagan was focused less on what was best for the party and more on settling old scores. McCain’s advisors had pushed hard for a unity ticket, but neither candidate would have it. Both Reagan and, especially, Mrs. Reagan could hardly stand to be in the same room with McCain.

As the turmoil swirled, rumors had persisted that Democratic nominee Barack Obama would attempt to court disaffected Reagan loyalists with his D.C. outsider image, looking to reform the way government worked. As the Republican Party hemorrhaged, McCain knew that any chance of a victory in the general election would rely on his ability to stop the bleeding, and fast.

Thus, the night he received the nod, the applause from his acceptance speech still shaking the foundations of the stadium, McCain, grinning from ear to ear, made a surprise request for Reagan to come to the podium by calling out, “Would my good friend Ron Reagan come on down, and bring Nancy?”

The McCain camp believed this gesture would go a long way to bridging the party’s unity gap and, perhaps more importantly, deflate the image of Reagan as a great public orator. “McCain bought into the perception that Reagan was still just an actor. He wanted the country to see him speak without a teleprompter because he thought Reagan would struggle. We all did,” a McCain advisor later admitted.

Reagan was livid. Earlier that morning he had unequivocally rejected an offer to appear on stage with McCain. McCain was now putting Reagan on the spot with the eyes of the nation watching.

So, Reagan rebuffed McCain, waving and shaking his head no, before smiling and giving McCain the thumbs up sign.

As far as Reagan was concerned, he had made his last speech of the 2008 campaign earlier that day as he met with his staff one last time to thank them for their hard work, telling the tear-filled room:

“The cause goes on. Nancy and I aren’t going back to sit on a rocking chair and say that’s all there is for us. We are going to stay in there and you stay in there with me. The cause is still there. Don’t give up your ideals, don’t compromise, don’t turn to expediency, don’t get cynical. It’s just one battle in a long war. Our cause will prevail because it is right.”

But as McCain’s family started waving Reagan down to the stage, the people in the convention hall erupted in chants: “We want Ron! We want Ron!”

Reluctant to disappoint the Republican faithful, Reagan stepped out of his skybox.

“I haven’t the foggiest idea what I’m going to say,” he told Nancy before striding down to the stage.

Yet Reagan took to the podium and began by thanking McCain before launching into his vision for the Party. Reagan did not stumble, as predicted, but instead delivered one of the most powerful speeches of his career:

“May I just say some words? There are cynics who say that a party platform is something that no one bothers to read and it doesn’t very often amount to much.

“Whether it is different this time than it has ever been before, I believe the Republican Party has a platform that is a banner of bold, unmistakable colors, with no pastel shades.

“We have just heard a call to arms based on that platform, and a call to us to really be successful in communicating and reveal to the American people the difference between this platform and the platform of the opposing party, which is nothing but a revamp and a reissue and a running of a late, late show of the thing that we have been hearing from them for the last 70 years. If I could just take a moment… I had an assignment the other day. Someone asked me to write for a time capsule that is going to be opened in Los Angeles a hundred years from now.

“It sounded like an easy assignment. They suggested I write something about the problems and the issues today. I set out to do so, riding down the coast in an automobile, looking at the blue Pacific out on one side and the Santa Ynez Mountains on the other, and I couldn’t help but wonder if it was going to be that beautiful a hundred years from now as it was on that summer day.

“Then as I tried to write—let your own minds turn to that task. You are going to write for people a hundred years from now, who know all about us. We know nothing about them. We don’t know what kind of a world they will be living in.

“And suddenly I thought to myself, if I write of the problems, they will be the domestic problems the Senator spoke of here tonight; the challenges confronting us, the erosion of freedom that has taken place under Democratic rule in this country, the invasion of private rights, the controls and restrictions on the vitality of the great free economy that we enjoy. These are our challenges that we must meet.

“And then again there is that challenge of which he spoke: that we live in a world in which the terrorists plot their next attack that can kill thousands of innocent lives in a single heartbeat.

“And suddenly it dawned on me; those who would read this letter a hundred years from now will know whether we met our challenges. Whether they have the freedoms that we have known up until now will depend on what we do here.

“Will they look back with appreciation and say, ‘Thank God for those people in 2008 who headed off that loss of freedom, who kept us now, one hundred years later, free?’

“And if we failed, they probably won’t get to read the letter at all because it spoke of individual freedom, and they won’t be allowed to talk of that or read of it.

“This is our challenge; and this is why here in this hall tonight, better than we have ever done before, we have got to quit talking to each other and about each other and go out and communicate to the world that we may be fewer in numbers than we have ever been, but we carry the message they are waiting for.

“We must go forth from here united, determined that what a great general said a few years ago is true: ‘there is no substitute for victory.’”

After Reagan’s speech the crowd stood stunned. Many had tears in their eyes.

McCain felt sick to his stomach, and his face drained of color. He strained to keep his smile as he and Reagan raised their arms up together above their heads to the deafening cheers of the crowd. His moment was lost. It would be Reagan’s speech and not his own dominating the following news cycles.

Worse yet, many in the room had been filled with a palpable sense of buyer’s remorse.

Aaron Bishop, a grassroots organizer from Virginia overheard the woman next to him mutter, “Oh my God, we’ve nominated the wrong man.”