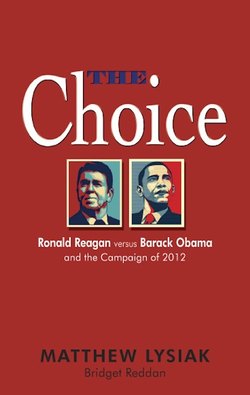

Читать книгу The Choice: Ronald Reagan Versus Barack Obama and the Campaign of 2012 - Matthew Ph.D Lysiak - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

Оглавление“You know, people will insist that 2008 had 366 days. I don’t believe it. I think it had 36,666 days,” Democratic strategist James Carville said as the year came to a close. Carville was speaking on his own behalf, as a pundit for CNN, but he could have easily been speaking for the entire nation.

It had been a miserable year, littered with lost jobs, lost national pride, and lost hope. The country was at war on two fronts, with the casualty count rising steadily in Afghanistan and Iraq, while Americans at home were struggling to adjust to the depressing new economic reality of soaring inflation and high unemployment. Senator John McCain, having lost the election by a landslide, disappeared into political memory.

The downturn spared no one. Young adults had begun to discover a college degree was no longer a guarantee of a good job. Senior citizens had a rude awakening when $7 trillion of wealth vanished from the stock market, devaluing their savings and forcing them out of retirement. Even the jet-setting crowd had started feeling the heat, especially those unfortunate enough to have invested with Bernie Madoff, whose $50 billion Ponzi scheme set off an epic buzz kill at cocktail parties and social scenes stretching from coast to coast.

Lurking beneath the jarring loss of wealth and jobs was a powerful shift in the philosophical premises that had long guided American economic policy. For the first time since the Great Depression, the public seemed ready to embrace bigger government. In a September 2008 Time Magazine article, “The New Liberal Order,” Peter Beinart wrote, “Americans want government to impose law and order—to keep their 401(k)s from going down, to keep their healthcare premiums from going up, to keep their jobs from going overseas—and they don’t much care whose heads Washington has to bash to do it.”

Adam Smith was out. Paul Krugman was in.

In October of 2008, former Treasury Secretary and Ayn Rand protégé Alan Greenspan publicly revoked his faith in the market, testifying before Congress that he had made a mistake in believing that banks operating in their own self-interests would do what was necessary to protect their institutions. Greenspan called it a flaw in the model that defines how the world works.

By that December, the phrase “too big to fail” had become a staple of the American lexicon, as the Treasury Department cherry-picked which businesses would be allowed to go under and which would be bailed out, printing billions of dollars that flooded into Wall Street, car manufacturers, and financial institutions. Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan captured the downtrodden mood of the country:

The sense you pick up is that people feel all trends lead downward from here, that the great days of America Rising are over, that the best is not yet to come but has already been. It is so non-American, so unlike us, to think this, and yet one picks it up everywhere, between the lines and in asides. The other night a man told me of his four children, and I congratulated him on bringing up so many. From nowhere he said, ‘I worry about their future.’ At another time he would have said, ‘Billy wants to be a doctor.’

As the year came to a close, Americans were ready for some good news. The storybook ascendancy of the little-known Illinois Senator had seemed like the perfect remedy. President-elect Barack Hussein Obama had won the highest percentage of the vote of any Democratic presidential candidate since Lyndon Johnson’s landslide in 1964 and the highest for a non-incumbent Democrat since 1932. Americans were ready for change. For many, Obama’s victory marked the dawn of a new golden age, ushering in an era of progressive government that could span generations.

It turned out the President had long coattails, too. The 2008 election had produced a Congress firmly rooted in Democrat control, and the most liberal configuration of power Washington, D.C., had seen since 1965. With a rising non-white population, an increasingly non-churchgoing youth, and a growing tendency for the college-educated to vote Democratic, the shift in political power promised to be long-lasting.

A widely distributed 51-page paper titled “New Progressive America” began making its rounds through liberal circles, touting the new permanent Democrat majority. The author, Ray Teixeira, wrote, “Progressive arguments are in the ascendancy and demographic and geographic trends should take America down a very different road than [the one that] has been traveled in the last eight years. We have moved from America the conservative to America the liberal.”

On January 20, 2009, the largest inauguration crowd in history braved the cold to hear about Obama’s new liberal vision:

“Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off and begin again the work of remaking the United States of America.

“That we are in the midst of crisis is now well understood. Our nation is at war against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred. Our economy is badly weakened, a consequence of greed and irresponsibility on the part of some, but also our collective failure to make hard choices and prepare the nation for a new age. Homes have been lost; jobs shed; businesses shuttered. Our healthcare is too costly; our schools fail too many, and each day brings further evidence that the ways we use energy strengthen our adversaries and threaten our planet.

“These are the indicators of crisis, subject to data and statistics. Less measurable but no less profound is a sapping of confidence across our land—a nagging fear that America’s decline is inevitable, and that the next generation must lower its sights.

“Today I say to you that the challenges we face are real. They are serious and they are many.

They will not be met easily or in a short span of time. But know this, America—they will be met. On this day, we gather because we have chosen hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord.”

The winds of history at his back, President Obama aggressively moved forward with his new mandate. He pushed through a laundry list of liberal policies: halting Guantanamo Bay trials, closing CIA “black sites,” outlining an environmentally friendly energy policy, and handing government agencies broad new regulatory powers to “make the market more accountable.”

However, the new President’s most daunting task would be saved for healing the nation’s stagnant economy. After inheriting an abysmal 7.8% unemployment rate and with economic indicators showing serious decline in nearly all sectors, the President’s first priority was to “put Americans back to work.” His solution? A massive $775 billion “stimulus” bill.

The White House administration argued that the bill would halt the climbing unemployment rate. They predicted unemployment would peak at 8% by the year’s end and shrink to less than 7% by 2011, whereas without it, they claimed, the rate would rise to 9% by 2010. Additionally, by offsetting the drop in private spending with the infusion of public money, the administration promised, the double-dip recession would end. They made the claim that spending almost $1 trillion would generate a $1.6 trillion return in the economy, in what became known as the “multiplier effect.”

To those concerned about the amount being spent, Obama answered: “What do you think a stimulus is? It is spending, that’s the whole point!”

As expected, the stimulus caused uproar among Republicans. Topping the list of complaints was the heft of the 647-page bill. Members of Congress said they needed more time to read its contents.

“We don’t have more time,” Obama told reporters at a White House press conference. “We are in a crisis, a national emergency of epic proportions. We can’t afford to wait another day to put the people back to work. The time to act is now.”

On February 17, 2010, Obama signed the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act into law. It was a historic and legislative victory for the administration. The week’s cover of Newsweek declared, “We’re All Socialists Now.”

On the surface, everything was going right for the Democrats. Sitting at the helm was the Party’s new leader, the gifted Obama, with a 68% approval rating—not seen for a new President since John F. Kennedy. He was smart and cool, and he had an ideological base firmly rooted in belief, whole-heartedly committed to working for a man they adored.

But all was not well in Obama’s world. During the weeks preceding passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, controversial details began to emerge. They painted an unflattering portrait of waste and government kickbacks to Democratic interest groups. The bill included $1 billion for Amtrak, $50 million for the National Endowment for the Arts, $400 million for global warming research, $2.4 billion for carbon-capture demonstration projects, and $650 million for digital TV conversion coupons. The Education Department received an extra $66 billion but was bound by the idea that “no recipient... shall use such funds to provide financial assistance to students to attend private elementary or secondary schools,” a move that clearly protected the Teacher’s Union. Solyndra, a solar panel manufacturer with ties to Democratic donors, was handed a $535 million federal loan guarantee despite its shaky financial footing.

Republican House Minority Leader John Boehner took a swipe at several items, including a sum of $400 million set aside for “national treasures,” to repair such things as the walls of the Tidal Basin near the Jefferson Memorial.

“What we’re seeing is disappointing,” said Mr. Boehner. “The package appears to be grounded in the flawed notion that we can simply borrow and spend our way back to prosperity.”

The mounting examples of waste began to draw detractors. Upset about another large spending proposal—this time a $1 billion mortgage bailout, CNBC’s Rick Santelli ranted:

“The government is promoting bad behavior! This is America! How many of you people want to pay for your neighbor’s mortgage [on a house] that has an extra bathroom and [they] can’t pay their bills? Cuba used to have mansions and a relatively decent economy,” he went on. “They moved from the individual to the collective and now they are driving Chevys, the last great car to come out of Detroit.”

By the end of February, voter discontent began mounting. The President’s 24% disapproval rating was twice as high as the average for a month-old presidency and twice the 12% disapproval rating that he had the month before. While Liberal and Independent support held fairly steady, the rookie Chief Executive’s approval among Republicans plunged from 41% to 30%, with an especially steep drop among Conservatives—from 36% at his inauguration to 22%. Middle-class Americans, touted as the group of people who would reap the most benefits from Obama’s plan, dropped their approval from 69% to 58%.

Democrats shrugged off the dip in the polls, ignored critics, and promised to push ahead with more legislation. “We are only in the beginning stages of remaking America,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi ominously told reporters. “My biggest fight has been between those who wanted to do something incremental and those who wanted to do something comprehensive. We won that fight and there’ll be more legislation to follow.”