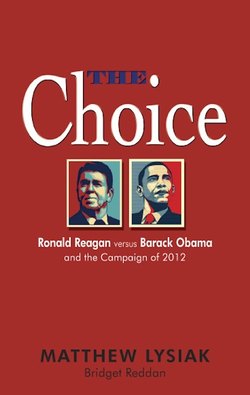

Читать книгу The Choice: Ronald Reagan Versus Barack Obama and the Campaign of 2012 - Matthew Ph.D Lysiak - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Ronald Reagan was physically and mentally exhausted.

Having just completed the toughest campaign of his life, and narrowly missing the top nomination, he decided to retreat to his 700-acre ranch high in the Santa Ynez Mountains. There, he gave himself two orders: rest and get the pain out of the way.

Resting proved the easier task. After years on the campaign trail, Reagan found he liked the solitude. No newspapers. No television. No Internet. No more kissing babies and shaking hands. But as much as the quiet provided comfort, Reagan could not ignore the pain of losing to a man he deemed a political and intellectual inferior.

John McCain’s muddled campaign, preceded by two terms of George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism,” had steered the Party’s message away from its fiscally conservative roots. Spending under GOP control had actually dwarfed that of spending under Democratic predecessors. The list of legislative accomplishments under the Bush administration read more like Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. “No Child Left Behind” shifted power from local educators to the Federal Government. The 2002 Farm Bill saw agriculture spending double its 1990s level. The 2003 Medicare prescription drug benefit was the biggest single expansion in the program’s history. By the time Bush left office, his vision of creating a permanent Republican majority had evaporated, along with his poll numbers. Not only was the United States left in the midst of a financial meltdown, it was also still at war in two countries. Judging by the outcome, McCain’s campaign had presented no viable solution to these problems. It was safe to say the Republican Party was in shambles.

Not everyone was willing to stand by quietly. Across the country, groups of discontented citizens began forming in protest. People from different walks of life, with different political affiliations, joined together under a shared ideology to protest exorbitant government spending and control. This leaderless group became known as the Tea Party—a name which was both a reference to the famous Boston strike against taxation and the acronym, “Taxed Enough Already.”

Meanwhile, believing that Reagan was too old, the conservative base was desperately searching for its new standard-bearer. This was a common theme. Reagan’s opponents had been writing him off for as long as he could remember.

Reagan had begun his foray into politics as a registered Democrat, even voting for Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election, but his political world had begun to tilt rightward when, after two disastrous Carter terms, he campaigned (as a Democrat) for George Bush as President. He had officially changed his party registration from Democrat to Republican in 1990.

Reagan had first burst on the national political scene on October 27, 1996, when he delivered a television address in support of Bob Dole’s fledgling presidential campaign. “A Time for Choosing” turned out to be the highlight of the lackluster Republican effort, and it had instantly put Reagan on the map as a political force. The soaring rhetoric had spelled out a clear, coherent, conservative message that had been sorely missing from Dole’s campaign.

Known simply as “The Speech,” Reagan’s ode to freedom became a rallying cry for conservatives across the country:

“This idea that government is beholden to the people, that it has no other source of power except the sovereign people, is still the newest and the most unique idea in all the long history of man’s relation to man.

“A government can’t control the economy without controlling people. And they know when a government sets out to do that, it must use force and coercion to achieve its purpose. They also knew, those Founding Fathers, that outside of its legitimate functions, government does nothing as well or as economically as the private sector of the economy.

“No government ever voluntarily reduces itself in size. So, governments’ programs, once launched, never disappear. Actually, a government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth.”

The blistering attack on liberal orthodoxy might have been too little too late to save Dole from his landslide loss to Bill Clinton, but the nationally broadcast speech made Reagan an instant hero among the conservative base.

After “The Speech,” requests for speaking engagements began to pour in to Reagan’s offices from all across the country—especially from colleges where Reagan possessed an almost cult-like following among young students. Reagan began a syndicated column and honed his political skills by touring the country, making speeches espousing his conservative principles.

When Reagan decided to run for governor of California in 1998, most in the political establishment treated his candidacy as a joke, but after defeating incumbent Governor Gray Davis, it was the “washed-up, B-list movie actor” who left laughing.

Reagan was even drafted by a group of fiscal conservatives to make a run for President, but after a half-hearted attempt he quickly withdrew his candidacy, lending his support to George W. Bush.

After balancing the budget in California, a feat most assumed at the time to be all but impossible, Reagan easily won reelection for the governorship in 2002. His star was rising. Many political pundits were already measuring his seat for the White House. Reagan entered the 2008 race heavily favored to win the nomination, but during the campaign his ineffectual ground game and frequent gaffes badly tarnished his image as a leader, even amongst his most loyal supporters.

Despite his inspired impromptu speech at the 2008 Republican Convention, it was a widely held belief that Reagan’s time had come and gone. That he had missed his moment.

But not everyone thought so. During the first week of February 2009, a group of disillusioned Americans, led by the wealthy Koch brothers, made a bold move toward Reagan, asking him to consider one more presidential run, this time under a third party. While Reagan gave no answer, once he got back to the Ranch, he couldn’t stop thinking about it. Though he made no formal statement, word was leaked to the press.

At first, Reagan stunned politicos, who assumed his age had disqualified him from seeking another run, when he appeared open to a third-party candidacy, telling reporters outside his ranch, “This could be one of those moments in time, I don’t know. I see statements of disaffection by people in both parties.”

Reagan, however, reversed course two days later in a phone interview with Don Imus, saying:

“I believe the Republican Party represents basically the thinking of the people across the country, if we can get the message across to the people. I believe that a third-party movement has the effect of dividing people who share the same philosophy and usually winds up, because of that division, electing those they set out to oppose. Is it a third party we need, or is it a new and revitalized second party, raising a banner of no pale pastels, but bold colors which make it unmistakably clear where we stand on all the issues troubling the people? Americans are hungry again to feel a sense of mission and greatness.”

In late February, he accepted the offer to give the keynote address at the Conservative Political Action Conference. In what was his first public appearance since the Minnesota convention, Reagan expanded on his Imus interview, outlining his vision for an improved Republican Party:

“Despite what some in the press might say, we who are proud to call ourselves ‘conservative’ are not a minority party; we are part of the great majority of Americans of both major parties and of most of the independents as well.

“I have always been puzzled by the inability of some political and media types to understand exactly what is meant by adherence to political principle. All too often in the press it is treated as a call for ideological purity. Whatever ideology may mean, and it seems to mean a variety of things depending upon who is using it, it always conjures up in my mind a picture of a rigid, irrational clinging to abstract theory in the face of reality. We have to recognize that in this country, ‘ideology’ is a scare word. And for good reason, Marxist-Leninism is, to give but one example, an ideology. All the facts of the real world have to be fitted to the Procrustean bed of Marx and Lenin. If the facts don’t happen to fit the ideology, the facts are chopped off and discarded.

“I consider this to be the complete opposite to principled Conservatism. If there is any political viewpoint in the world which is free from slavish adherence to abstraction, it is American Conservatism.

“When a conservative states that the free market is the best mechanism ever devised by the mind of man to meet material needs, he is merely stating what a careful examination of the real world has told him is the truth.

“When a conservative quotes Jefferson that government that is the closest to the people is best, it is because he knows that Jefferson risked his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor to make certain that what he and his fellow patriots learned from experience was not crushed by an ideology of an empire.

“Conservatism is the antithesis of the kind of ideological fanaticism that has brought so much horror and destruction to the world. The common sense and common decency of ordinary men and ordinary women, working out their own lives in their own ways[:] this is the heart of American Conservatism today. Conservative wisdom and principles are derived from willingness to learn, not just from what is going on now, but from what has happened before.

“The principles of Conservatism are sound because they are based on what men and women have discovered in not just one generation or a dozen, but in all the combined experience of mankind.

“The country cannot be limited to the country club, big business image that it is burdened with today. The new Republican Party I am speaking about is going to have room for the working class man and woman, for the farmer, for the cop on the beat.

“Our task is not to sell a philosophy,” Reagan continued, “but to make the majority of Americans, who already share that political philosophy, see that modern Conservatism offers them a political home. We are not a political cult; we are members of a majority. Let’s act and talk like it. The job is ours and the job must be done. If not by us, who? If not now, when? Our party must be the party of the individual. It must not sell out the individual to cater to the group. No greater challenge faces our society today than ensuring that each one of us can maintain his dignity and his identity in an increasingly complex, centralized society.

“Extreme taxation, excessive controls, oppressive government competition with business, galloping inflation, frustrated minorities, and forgotten Americans are not the products of free enterprise. They are the residue of centralized bureaucracy, of government by a self-appointed elite.

“Our party must be based on the kind of leadership that grows and takes its strength from the people. Any organization is in actuality only the lengthened shadows of its members. A political party is a mechanical structure created to further a cause. The cause, not the mechanism, brings and holds members together; and our cause must be to rediscover, reassert, and reapply America’s spiritual heritage to our national affairs.

“Then with God’s help we shall indeed be as a city upon a hill, with the eyes of all people upon us.”

The standing ovation lasted several minutes. Reagan was not only taking on the current administration; he was also confronting the GOP elites that had run the party into the ground. Perhaps, more importantly, Reagan was giving the party hope, a hope its members had not felt since Obama had been elected.

“For the first time in a very long time it feels good to be a Conservative again,” CPAC member Brian Dula told reporters outside the hall, before lamenting, “If only Ronald Reagan was ten years younger.”