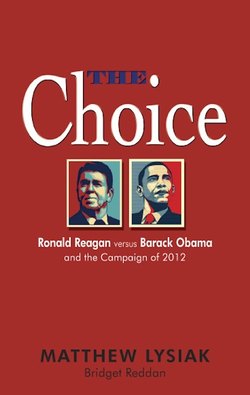

Читать книгу The Choice: Ronald Reagan Versus Barack Obama and the Campaign of 2012 - Matthew Ph.D Lysiak - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

Оглавление“Mr. President, this is a big fucking deal.”

It was the morning of March 23, 2010: a date for the history books. President Obama had just signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act into law, and the microphones in the East Room of the White House inadvertently picked up the Vice President’s words and broadcast them live across the nation.

For once, the gaffe-prone VP was understated. The $1 trillion federal legislation was the most expansive legality enacted since the New Deal, promising to do the seemingly impossible by providing universal health coverage to all Americans while lowering costs and shrinking the deficit.

Victoria Reggie Kennedy, the widow of Senator Edward Kennedy, who had made universal healthcare his life’s work, had stood at Obama’s side during the ceremony along with 11-year-old Marcales Owens, who had become a poster child for health reform after his uninsured mother died of cancer. The President had seemed to sense the gravity of the moment, saying, “The bill I’m signing will set in motion reforms that generations of Americans have fought for and marched for and hungered to see. Today we are affirming that essential truth, a truth every generation is called to rediscover for itself, that we are not a nation that scales back its aspirations.”

It had been a stunning turnaround for the President and his party who, only two months earlier, had believed the bill to be dead. Scott Brown, the Massachusetts Republican who had centered his campaign on opposition to the legislation, had shocked the nation by winning the Senate seat formerly held by Ted Kennedy. This historic rebuke had deprived Obama of the 60-vote super majority necessary to pass the bill.

The results in Massachusetts had marked the third time in three months that Obama could not deliver for a Democratic candidate. In November, he had abetted the defeat of Creigh Deeds in the Virginia governor’s race and failed to prevent Democratic Governor Jon Corzine’s ouster in New Jersey. If the American people were sending the President a message, he was not getting it. While most Americans favored reform, they were overwhelmingly opposed to the kind of sweeping government intervention Democrats were proposing. Polls showed that the nation wanted the administration’s attention focused on the struggling economy.

Despite much diligence, the Republican’s work in Congress to prevent the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, was undermined in what many considered to be an underhanded maneuver. Having lost the super-majority and the votes needed to pass the Act, the Democrats bypassed a Republican filibuster with a shockingly controversial maneuver—reconciliation. A tool intended only for budget adjustments, a reconciliation caps debate at twenty hours and requires only fifty-one votes for a majority. Because of this, the Republicans’ gain of Brown’s Senate seat was inconsequential. Despite much opposition, Democrats were able to ram through the unpopular legislation.

Their decision to ignore the will of the people had been bold, inspired, and politically toxic. Government spending was reaching a critical point because the economy, while showing signs of occasional growth, still was not creating jobs. The economic uncertainty in Washington had created an unwelcome environment for investors: the wealthy held on to their capital rather than risking it on new ventures. Congress had passed other industry-specific stimulus bills, like “Cash for Clunkers,” a failing program designed to boost auto sales by paying people for their old cars in hopes they would turn around and buy new ones. Other new bills had included the $8,000 per homebuyer tax credit, mortgage payment relief, and a new jobless pay extension of up to 99 weeks. Yet all of this legislation had merely stolen car and home purchases from the future, with sales falling immediately once the tax benefits expired.

The recovery that appeared to have begun in the summer of 2009 had decelerated. While gross domestic product (GDP) growth had hit 5% in the fourth quarter on the backs of an inventory rebound and overseas expansion, it had slumped to 1.6% in the second quarter. The unemployment rate had hit 9.6% after three consecutive months of job losses. Never before had the government spent so much and intervened so directly in credit allocation to spur economic growth. Yet in return for adding nearly $3 trillion in Federal debt in two years’ time, the government found that 14.9 million Americans remained unemployed.

The 2,400-page Affordable Care Act came with a tidal wave of regulations which, when taken together, promised to fundamentally alter the lives of each and every American. The President’s program centralized medical decisions in Washington. Politicians now were able to decide what healthcare plans should be offered, what benefits should be included, how much people should pay in premiums, and what medical trade-offs should be made.

Opponents protested immediately and in depth. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich said, “Turning power over to the government could lead to selective standards and euthanasia,” meaning the Affordable Care Act would perversely discourage cost-saving provisions by administrative action to limit excessive care or attempts to prevent fraud. The Act would restrict the sort of health insurance policies, such as consumer-oriented health savings accounts, that could be offered. Insurers would be penalized for unpredictable changes in healthcare costs. Skeptics warned the new measures would ultimately drive some insurers out of the market or even out of business, while the Congressional Budget Office cautioned, “A policy that affected a majority of issuers would be likely to substantially reduce flexibility in terms of the types, prices, and number of private sellers of health insurance.”

Moments after the legislation was signed into law Republicans vowed to repeal the measure. Attorney generals in more than a dozen states filed lawsuits contending the measure’s mandate that forced all Americans to purchase healthcare or pay a fine was unconstitutional.

“This is a somber day for the American people,” said House Republican Leader John Boehner. “By signing this bill, President Obama is abandoning our founding principle that government governs best when it governs closest to the people.”

Opposition to the Act unified Libertarians, moderate Republicans, and even blue-collar Democrats in the call for reform. As a result, the Tea Party was increasing in mass and magnitude, and it was in the Tea Party that Ronald Reagan found his third act.

Speaking to a group of Tea Party activists at the Des Moines Small Business Owner’s Convention, Reagan said, “The government in Washington is spending some seven million dollars every minute I talk to you. There’s no connection between my talk and their spending, and if they stop spending, I’ll stop talking.”

At every stop, Americans were asking Reagan to throw his hat in the ring again. He often smiled, sometimes winking at the suggestion, but publicly stayed mum on the subject. Privately, though, Reagan was preparing, telling his advisors, “Get ready. I’m going to make one last jump.”