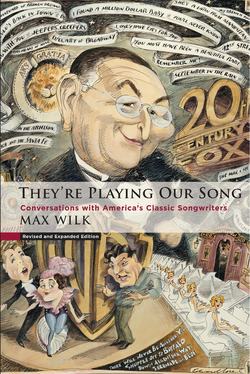

Читать книгу They're Playing Our Song - Max Wilk - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

“All the Things You Are” · Jerome Kern ·

ОглавлениеYOU CAN’T SAY anyone’s bringing Kern back; it seems that his music has always been there.

For our elders, there were his early operettas, lovely concoctions that culminated with those elegant little Princess Theatre shows from 1915 on. For our parents, there were his later Broadway operettas, the joyous Sally, and Sunny, and then Show Boat. Came the ’30s and he was turning out The Cat and the Fiddle, Roberta, Music in the Air, and Very Warm for May. And for us—and now for our own kids, thanks to TV and those film-revival houses—there’s his remarkably fruitful Hollywood period, when he supplied all those rich scores for Fred and Ginger, for Gene and Rita, and for Irene Dunne, at the behest of producers who rarely realized how fortunate they were to have his services.

Songwriters and lyricists and musicians rarely agree on anything, least of all on someone else’s music, but mention any melody of Jerome Kern’s and its potential for posterity—and the argument’s over. It was always so. “Kern,” George Gershwin wrote in a letter to Isaac Goldberg, “was the first composer who made me conscious that popular music was of inferior quality, and that musical-comedy music was made of better material. I followed Kern’s work and studied each song that he composed. I paid him the tribute of frank imitation, and many things that I wrote at this time [1916] sounded as though Kern had written them himself.” Richard Rodgers says, “Kern had his musical roots in the fertile Middle European and English school of operetta-writing, and amalgamated it with everything that was fresh in the American scene to give us something wonderfully new and clear in music-writing.” Kern and Irving Berlin maintained a staunch mutual-admiration society. And whenever any of Kern’s lyricists—Hammerstein, Harbach, Ira Gershwin, Dorothy Fields, E. Y. Harburg, Johnny Mercer, Leo Robin, or P. G. Wodehouse—discusses his music, it falls into a special category.

Jerome Kern

The years have flashed past so quickly since that sad day in November 1945 when Kern collapsed and died, in cruel anonymity, on a Manhattan street. To listen to his music gives no indication of the sort of man he was. But to those who knew Kern, who worked with him, were exposed to his strong personality—querulous, iron-willed, assertive—the man himself remains, like his music, very much there.

Here, then, a few recollections …

From Edward Laska (as told to Variety), who collaborated on Kern’s first song hit, in 1905, when the young composer was twenty years old:

It was in 1905 … that I was in the midst of writing a musical comedy with the late George McManus, Sam Lehman and Willard Holcomb, based on Mac’s first two comic strips, The Jolly Girls and Panhandle Pete.

… I had already achieved a year’s experience and a little success in writing and getting songs published … and at the Harms rendezvous [T. B. Harms & Co., then headed by Max Dreyfus] I often chatted with a kid who was an aspiring composer … he wished he could try me out sometime with some of my lyrics. New composers have great difficulty in getting lyricists to work with them, and in my case I was a double difficulty, for I usually wrote both the words and the music myself….

However, I liked the kid—I say “kid” although he was really only one year younger than I, but at that period of life one year is an enormous difference. I decided to do some songs with him and waited for the right opportunity or idea to come up….

I came suddenly … I had written two songs for a musical comedy that had just opened in Albany, under the management of Frank L. Perley. The show was called The Girl and the Bandit, and “My Sweet Little Caraboo,” an Indian song of the type that was the rage at that time, turned out to be the hit of the show…. I visited Mr. Perley to see if there was something new he needed, for songs are often taken out during those tryout weeks. “Yes,” he said. “Write me a duet for Joe Myron and—” I can’t even recall the name of the actress, but she was even larger than Joe Myron, and he weighed at least 290.

… I got to the Harms building and there was my young friend, as usual, with a straw hat on, of which the top was knocked out, and a long black cigar in his mouth, being cold-smoked—I don’t think I ever saw him really smoke one, but it seemed to inspire him, as he ground out melody after melody without ever bothering to jot them down. He seemed to have an unfathomable well of them…. “Jerry,” I said … “we’ve got to do a song,” and then I gave him the title “How’d You Like to Spoon with Me?” and just its rough rhythm. At once, as though it were a song he had known all his life, he improvised a tune that fit it exactly. “Swell,” I said. “Now toss me a verse,” and again, in just as long as it takes to play it, he gave me a melody for a fitting verse. At once I wrote what we call a dummy lyric…. Jerry was elated and he went over it a few times, when George McManus arrived and I sang the rough dummy lyric to him as Jerry played. “Very good,” said Mac, little foreseeing that he was commenting on what was to be the very first song hit of one of America’s top composers of musical comedy, and we should not overlook the fact that McManus, too, was yet to achieve his greatest success, Bringing Up Father.

The next afternoon I appeared with the completed lyric, and we rehearsed ourselves, Jerry to play and I to sing.

Over to Perley we sped, and when several attractive but later-arriving females were ushered in to him ahead of us, Jerry got sore and wouldn’t take it. “Come on, Ed, we’ll go to Hayman,” so we told the receptionist that we’d be back later, and off we went to Alf Hayman, who was Charles Frohman’s general manager, stop the old Empire Theatre.

Hayman liked the song but wanted me to change the word “spoon,” as it was entirely unknown in England, and if I would fix it he would have Edna May sing it there. She was then the American sensation of England, as the Salvation Army lass in the famous Belle of New York.

Out on the street we discussed the situation, and Jerry agreed that it would kill the song to eliminate the main title word “spoon,” and I suggested we go over to the Shuberts.

The Shuberts were then just starting as producers and had one show on and another in rehearsal. Their office was atop the Lyric Theatre on 42nd Street, which had been built for them by the socialite composer Reginald De Koven, especially famous for his “Oh, Promise Me.”

Sam Shubert, the leading one of the three brothers, came out to see us, and up chirped Jerry, “We are protégés of Reginald De Koven and have a song for you to hear.” I nearly collapsed at hearing who we were, and Shubert, impressed with our connection, led us to an adjoining room with a piano. Jerry played and I sang. All the brothers and several of their managers present were enthusiastic, and at once agreed to feature the song in their then-rehearsing show, The Earl and the Girl, to star Eddie Foy, at the Casino Theatre.

Out in the street, we kids, nineteen and twenty respectively, slapped each other on the back and I think we gleefully went into an apothecary’s to have a couple of ice-cream sodas. We hardly could realize that we were to have the featured song of this forthcoming Casino Theatre production….

The show … opened in Chicago in about two weeks. Jerry went out, and a wire to me told of the song’s enormous hit. It swept the entire country and then on to England, and all the rest of the English-singing world, and despite Alf Hayman’s skepticism about the word “spoon,” it then became a well-known term throughout Great Britain and the song was a stupendous hit…. In fact, I received a charming letter from Jerry’s widow in response to my condolence when he passed … in which she told me how she met Jerry when she was seventeen, and when he mentioned that he had composed “How’d You Like to Spoon with Me?” she thought he was jesting, for since her childhood she had known it and always thought it was an old English song…. Sweetly, she added that the little song had been a great part of the beginning of their thirty-five-year romance….

“How’d You Like to Spoon with Me?” was introduced in the London Gaieties, and it led to Kern doing songs for Charles Frohman’s English importations in New York…. From this writing of several songs only for an English production, he gradually got to do a complete score to the lyrics of an English author he had encouraged to come here to America, and who has remained here intermittently since then, P. G. Wodehouse.

… Kern’s early idol was the late Leslie Stuart, the English author of the famous Floradora…. And it might be interesting to note that Kern was the cornerstone of the music-publishing empire of the Dreyfus brothers, Max and Louis [Chappell, et al.], and it was greatly due to Kern’s enormous success that, like the Pied Piper of Hamlin, composers followed him to Max Dreyfus for great advice and guidance….

… Little did we know that day when we wrote “How’d You Like to Spoon with Me?” that it was the beginning of a great composer’s career….

Edward Laska died three years after he wrote this, but P. G. Wodehouse is very much still with us, and so are his recollections of his good friend and collaborator. He writes:

Yes, it certainly was fun doing the princess shows.1 We were all reasonably young and very confident that we were on the verge of big things … though our first effect, Have a Heart, had only been one of those Henry W. Savage things—not much on Broadway but five years on the road, like most of Savage’s. The great thing was that Guy [Bolton] and Jerry had put them in right with Very Good, Eddie, so we assumed that the next one, Oh Boy!, was bound to be a success. There’s nothing that bucks you up like having a manager who just signs the contract and tells you to go ahead and doesn’t make any suggestions or criticisms. And Oh Boy! turned out to be a smash, though we were dubious about it on the preliminary road tour—especially when I overheard a lady in Schenectady say disgustedly as she came out, “I do like a show with some jokes in it.”

My part in the Princess productions was always fun because Jerry was such a perfect composer to work with. I had met him in London in 1906 when I had a job at three pounds a week writing encore verses for Seymour Hicks and Ellaline Terriss (who died not long ago, aged 100). One day Hicks said that Frohman had brought over a young American composer who he said was promising, and he introduced me to Jerry, who looked about fifteen. He had down two or three songs, including a terrific tune to which I wrote a lyric called “Mister Chamberlain.” The lyric wasn’t much, but the music was irresistible and it always got at least six encores, which kept me busy writing encore verses. Years later I met Jerry again at the opening of Very Good, Eddie, which I had gone to as the dramatic critic of Vanity Fair. We fell on each other’s necks and he insisted on my doing the lyrics for the next Princess show.

Our collaboration was conducted mostly over the telephone, as I was living in Great Neck and he in Bronxville. I would go to bed all set for a refreshing sleep, and at about three in the morning the phone would wake me, and it would be Jerry, who had just got a great tune. He played it to me over the phone and I took down a dummy.

Jerry hated to turn in at night. I remember once I was staying at his place and mentioned that I had taken a house in Bellport. This was at about two A.M. “Let’s go and take a look at it,” said Jerry. “What, now?” “Of course.” So we set out, arriving at about five, and I was fully occupied on the return journey with prodding Jerry in the ribs, he having dozed off at the wheel.

What I loved in Jerry was his indomitable spirit. It was before my time, but I was told that in his struggling days he had managed to sell a song to one of the Charles Dillingham shows. He attended an orchestra rehearsal and frowned a dark frown. “Is that the way you’re going to play my song?” he asked. He was assured that it was. He immediately collected all the orchestra parts and walked out with them. And that was at a point in his career when he would have given his eye teeth to have a song in a Dillingham show. He was a perfectionist, and was prepared to starve in the gutter rather than have his stuff done wrong.

Nothing could have been more pleasant than my relations with Jerry. Not a cross word, as they say. But I am told that after Show Boat he became a little difficult and had a good deal to say to his lyricists about their defects. He also changed from the rollicking spirit of the Princess days into what you might call The Music Master. I never saw that side of him. To me he has always been the Jerry of Oh Boy! and Oh, Lady! Lady! and the dozen other shows we did together.

Perhaps the most famous of all of the Wodehouse-Kern collaborations will remain the delicately shaped torch song “My Bill,” which was written in 1918 but was dropped from Oh, Lady! Lady! Three years later, in 1921, it was tried again in Marilyn Miller’s starring show Sally. Again it was dropped. Finally, in a revised version, it came to rest, happily and permanently, in Show Boat. Wodehouse adds:

What a strange history that song had! I wrote it for Vivienne Segal to sing in Oh, Lady! and we cut it out as too slow. And I think we were right. (Jerry must have thought so, or the cut would never had been made, because he and Guy and I were a pretty haughty trio by that time and would merely have said, “Oh, yeah?” if the management had suggested it.) It was certainly a bit of luck for it that it was not done in Oh, Lady! Vivienne would have sung it beautifully, but the atmosphere would have been all wrong for it, Oh, Lady! being a rapid farce. It was probably Jerry who suggested cutting it, for in addition to all his gifts as a composer he was a wonderful showman with an instinct for what was right and what wasn’t, and he would never have hesitated to jettison his best melody if he thought the song did not fit.

I never can remember if I wrote the lyric and he set it or the other way around. The way we usually worked was that he wrote the melody and I put words to it, except in the case of comic trios like “Bongo on the Congo” and “Sir Galahad,” where the words came first.

Kern lived and worked for many years in Bronxville, New York, where, in addition to creating the music for Broadway successes such as Sally, Sunny, Show Boat, Sweet Adeline, and Roberta, he indulged in what was to become his major passion, the collecting of rare books. Wesley Towner writes, in The Elegant Auctioneers:

He could not pass a bookstore. A small, amicable, quiet man, with tremendous stores of nervous energy, Kern wore horn-rimmed glasses, smoked constantly, poured forth hundreds of facile tunes with the radio blaring in his ears, and modestly called himself a dull fellow with a little talent and lots of luck. In a chronic state of collectomania, he amassed in his Bronxville, New York house, a superlative library of rare first editions, manuscripts, and autograph letters…. He was a prudent buyer. An insomniac with a prodigious memory, the Melody King, thought not much of a reader, nightly pored over old volumes and acquired an impressive knowledge of collecting points and technicalities. His first editions were among the finest extant, many of them unique in that they contained notes or autographed sentiments by the authors…. Nor was he, for all the immensity of his earnings, an easy mark for the price-gouging dealer. “What, three hundred dollars for a book!” he would exclaim affably. “That’s a lot of money to me.”

It was perhaps the chase that intrigued Kern most. For once in possession of his enviable cache, he decided to sell. His books were a source of worry, he said. But he also may have had a premonition. Luck had dogged him all his life. He had hit the jackpot with almost everything he wrote; he had missed embarking on the Lusitania, and probable death on her ill-fated voyage, because an alarm clock unaccountably stopped and failed to wake him up. Now, in the closing months of 1928, when Wall Street still portended sky-high profits, some instinct told him to cash in not only his books but also his stocks at their inflated value….

The auction of Kern’s books remains one of the landmark sales in the history of American auction houses. He consigned 1,482 items to the Anderson Galleries, a collection that he had spent nearly half a million dollars acquiring. The ensuing sale was held over ten sessions.

When all the chips were down, and the tenth session ended, the dogged players had heaped into the pot $1,729,462 for Kern’s half-million dollars’ worth of books….

… Kern paused in the composition of his newest operetta to send Mitchell Kennerley and his staff a gracious telegram of congratulation and appreciation for their “wonderful conduct of the auction.” The next day he went out and bought a book, the first of a new collection that would be sold for his estate by the Parke-Bernet, though for no such astounding figure, far off in 1962.

“I worked with Kern perhaps more than any other composer,” says Robert Russell Bennett, the great arranger-conductor. “I went down to Palm Beach and lived on his boat with him once before he went out to Hollywood with a show. First thing he ever did in Hollywood, way back, 1930. A thing called Men in the Sky. And it came out and died a horrible death. One of the few pictures in those days that simply didn’t pay its way. I worked with him on that. He came back with one number that started out: ‘Pat’s going to have some luck, Pat’s going to have some luck today.’ It didn’t get into the show that it was for, but he liked the little 6/8 tune, took it out, and the next show, he brought it out again and said, ‘Here’s an old friend of yours.’ And he was trying it out, and it didn’t go in that show. So the next time it came up I said, ‘Well, maybe you can use Pat in this show.’ And he laughed and said, ‘Poor old man, we’ll never see him again.’

“Which is a quote from Ivor Novello, who was a very cute wit in London. I remember once when we were walking past Stone’s restaurant on Panton Street in London—Ivor Novello, Kern, and Vivian Ellis, I think—and Novello turned to me and said, ‘I say, shall we lapidize?’ “What do you mean, old boy?’ I asked. And he said, ‘Turn into Stone’s!’

“Anyway, the ‘Pat’ line came from Novello. One time they all went to the theatre, and Novello sat in the box with Kern where they’d been given seats to see this performance. And an actor came on in the first act, and as he made an exit Ivor said, ‘Poor old man, we’ll never see him again.’ And Kern said, ‘Oh, Ivor, what are you talking about? He comes back in the second act—it’s a very important part.’ So Novello says, ‘We’re not going to see him again because we’re jolly well getting out of here!’ That’s what Jerry was referring to, about his own little song.

“You just wouldn’t know where to start in talking about Kern. He’s an absolutely fantastic character. It was a different stunt every day. He’d wake up and say, ‘How’m I going to shock them today?’ Kern used to say to me, ‘Anybody that dislikes Beethoven—that’s all right with me. I have no use for him.’ Kern didn’t think that statement was silly.

“And he came up to me on the boat one time—we used to travel by sea all the time, going back and forth from shows in Europe. And he comes across the dining saloon and he stood at my table and put this little head of his to one side, and he said, ‘They can say all they want to, but Brahms is just a big pile of gymnastics, with a lot of material under it that even Lou—[a current pop songwriter] wouldn’t write!’

“I said, ‘Jerry, you might as well go back and eat, because you don’t have to listen to Brahms unless you want to, and I have to listen to Lou—all the time.’ Which meant I also had to listen to Jerome Kern!”

“I used to go up to Bronxville and visit a good deal,” says Irving Caesar. “Jerry lived there, and so did his good friend and publisher, Max Dreyfus. Jerry had great charm. Most fine piano players have that, you know. And he was very clever about certain things. He’d never say anything against another composer; he had a devilish way of getting you to do that. We’d be sitting at the table; some show had recently opened, and Jerry would start to praise it lavishly. ‘Never have I heard such great music!’ he’d say. ‘Never have I heard such magnificent lyrics!’ And he’d carry on in that fashion until the rest of us would jump in and say, ‘Oh, stop it—you know that stuff is perfectly awful!’ And he’d sit there beaming. Absolutely devilish, that ploy of his.”

Kern made several trips to California in the early days of the sound films, with varying success, but it wasn’t until 1934 that he accepted a lucrative contract and made a permanent move to Beverly Hills. He very much enjoyed living in California; within a few short blocks of his comfortable home were many of his New York friends and fellow composers.

There he wrote with Oscar Hammerstein, and later with Dorothy Fields, Ira Gershwin, and Leo Robin. He became very close friends with Harry Warren; the two composers enjoyed each other’s company hugely.

“Jerry was quite a character,” says Warren. “He loved fun, he loved jokes. He was a great worker. He had a guy named Charlie Miller, meek little chap, who was his sort of musical amanuensis, you know. He’d call Charlie up in the middle of the night, and say, ‘Charlie, listen.’ He had a phone near the piano, and he’d play a melody and wake poor Charlie up every night. And finally, one night, I don’t know what happened, he played something, and when he got to the release, poor Charlie finally got brave, and he said, ‘Jerry, I don’t like it.’ And Jerry said, ‘Why?’ Charlie said, ‘Well, it doesn’t sound like Kern.’ He waited for the roof to fall in, but all Kern said was, ‘I guess maybe you’re right, Charlie.’

“He loved camaraderie, he loved fun. Max Dreyfus used to call him a brain-picker, you know. You couldn’t tell Jerry anything without him going into full details. ‘Wait a minute,’ he’d say. ‘Just start at the beginning, let’s hear it, word by word.’ Even in a restaurant he’d call the maître d’—we used to go to dinner with him and Mrs. Kern—and he’d pick up the menu and he would see something he didn’t know. Now, he’d been all over the world, Europe and lots of places, but he’d see a dish that he’d probably never heard of, so he’d call the maître d’ over. ‘What is this?’ ‘Oh, well,’ says the maître d’, ‘this is some sort of—‘ Jerry says, ‘Wait a minute, start slowly. Tell me what it is.’ And he’d tell him, you see. And Jerry says, ‘How do you cook it?’ ‘Well, you cook it in the—‘ He says, ‘Now wait a minute—step by step, please.’ The whole recipe, step by step!

“Quite a man. He had another gag he used to do. He’d say, ‘Come on over tomorrow night.’ Harold Arlen, myself, and a whole gang of composers. And he would say, ‘Let’s play capitals of the U.S.’ Who would win? Him, you know. He’d cram up on them in the afternoon! Whatever game he was going to play that night, he’d start preparing in the afternoon.”

“I got along very well with him,” says Ira Gershwin. “He liked me. But I wasn’t used to working with anyone like that, you know. We started first on Cover Girl. He would say, ‘Here’—and hand me tunes. He’d say, ‘We have to use this,’ and he played me a sixteen-bar schottische. Rather monotonous. I said, ‘Very nice, Jerry, but I’ll have to find a spot for it, you know.’ And every time we’d keep on working—we worked a long time on that thing—every time he’d say, ‘Have you done that schottische yet?’ And I’d say, ‘No, I’m waiting for a spot.’2

“Finally, at the very end we had to write a title song, and I said, ‘Jerry, I think I can find that!’ It was that schottische! And that was the last thing I wrote in the picture—the thing he had given me so many months back to write up!

“Oh, he was a brilliant man. No question about his ability and talent. But he was a strange man. One day he said to me—he lived right around the corner here in Beverly Hills—‘I’m surprised your brother used actual automobile horns in American in Paris, realistic things like that.’ Couple of years later he writes ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris,’ using auto horns! And I hadn’t thought about it at the time, but when he did that show with Oscar Hammerstein about Vienna, Music in the Air, he was very proud that they’d gotten the actual effect of the chandeliers in the wind, the tinkling of the chandeliers. So he was for realism … that way.

“You know, I remember when radio came in, Kern saying, ‘I’m not going to let my songs be played!’ Actually, it wasn’t that he didn’t want them broadcast; he was greatly annoyed by some of the versions of his songs on the air, whether live or recorded. What he hoped for was to be able in some way to make sure that he could negate any recording that would not do justice to his work … but of course this was an impossibility. With more and more record companies popping up and with so many various recordings of any hit song, it was wholly impractical for any creator to control the manner in which his work was presented.

“Do you realize that Kern once had four shows in one year? My brother George rehearsed one of them, I think—Love of Mike or Rockabye Baby, one of those. He was the pianist. Of course, Kern could work very fast. I remember for one show he locked Mike Rourke up in a room at the Hotel Astor. Mike Rourke wrote under the name of ‘Herbert Reynolds.’ An old Irishman, he’d been a newspaperman in Ireland. Kern wouldn’t let him out! He would shove the lead sheets to him under the door … and in two weeks he had the whole score done. Kern would give Rourke the tunes first, and he’d say, ‘This fits such and such.’ That’s how he could turn out that many shows in a year.

“But when Kern said something rather arbitrary,” adds Gershwin, “I just always shrugged my shoulders.”

“When I was a young kid,” says Margaret Whiting, one of the two talented daughters of Richard Whiting, the composer, “my father, if he were working on a score or something else and couldn’t get out to the golf course to play a game, would go to a little pitch-and-putt course which was right below our house, Comstock Avenue at Beverly Glen. And I’d go over with him, and we’d always bump into Harry Warren and Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, sometimes Arthur Schwartz, and they’d all practice their golf swings. They’d talk about different songs, and then afterwards they’d take me over to their houses, and that is how I came to hear so many film scores before they were even published.

“I remember Kern calling me up one day after my father passed away, and he said, ‘Your father said you were the greatest judge of songs in the business, and I want you to come over.’ In other words, what he’d used to do with my father, he now wanted to do with me—use our opinions. He played me several songs; one was ‘I’m Old Fashioned,’ another was ‘Dearly Beloved.’

“He said, ‘Well, what do you think?’ I was so nervous. You see, my father was my father, and I knew that he was great, but he was my father. I could say, ‘I don’t like that song’ to my father … but how could you say that to Jerome Kern? I almost died.

“Luckily enough, it happened that these were two of Kern’s greatest songs, so I said, ‘Well, what can you say about perfection?’ I found one little thing that I thought could be changed. Kern said, ‘Well, that’s very good advice, Margaret. I’ll consider that.’”

“I was completely in awe of Kern from the minute we got together,” says Leo Robin, “and it cramped my style a little bit. He was a very nervous, impatient man, very erudite—I remember once I used the word ‘encyclopediac’ in referring to a man we knew, and Kern said, ‘Encyclopedic.’ He was that kind of a person.

“A very cultured musician, too; he knew music and he knew orchestration. What can you say about Kern? When we did the picture Centennial Summer he said to me, ‘Look, we’re going to do this picture with straight actors—there’s not one singer in the picture. I’ve never done that before.’ So he took a big gamble on the project. After we got started, he used to call me up every day, bugging me—‘You got anything yet?’ I wanted so much to please him and to measure up to his high standards that I don’t think I did my best work in that picture. But I had one song that Kern liked very much—‘In Love in Vain.’ He used to play it at parties.”

*

Harry Warren recalls: “I was sitting with him out at Metro one day when they were making a picture of his life story—you know, Look for the Silver Lining. We were out on the stage, and they were recording. They played the verse to one of Jerry’s songs. I don’t remember exactly what happened, but they didn’t get into the verse the way it had been written, and Jerry was so upset. He couldn’t understand why they did that. So he called Roger Edens, the arranger, over and asked who’d done it and why, and you know all those studio bastards were all the same. He said, ‘Well, Mr. Kern, we had to do that for some reason that’s technical,’ which is a lot of crap to me, you know, because I’d been in the picture business before this, thirty years. They’d made a change, and that was that.”

“You know the funny thing about Kern,” says Robert Russell Bennett, “he was terribly affectionate when there was a show coming up, and then I never heard from him until the next show was due. And we were very good friends; in fact, on the road, when we’d go out with shows, we’d eat together, play bridge together. And then the show would open in New York. Kern might as well not exist. I might as well not exist. Never heard a word from him. Then, maybe in one or two years, I’d get a note or a little letter, and I’d say to my wife, ‘Oh-oh, another show coming up.’ The letter would say nothing about the show, but then I knew I was going to get a phone call soon and he’d say, ‘How’re you fixed for such-and-such dates?’

“You know he died twice? They brought him to life after the first time he had a stroke. His heart had actually stopped beating, and yet the doctors out in California were actually able to revive him and get him going again. So he spent about eight years more, as he referred to it. on borrowed time. That was when he wrote so many of those beautiful things like ‘Long Ago and Far Away.’ Then he collapsed here on the street in New York, and they took the body over to Welfare Island. Nobody knew who he was. Finally his friends located the body and went out and rescued it from a burial in Potter’s Field.

“I went to the funeral, and Oscar Hammerstein got up and did one of his beautiful eulogies, just a lovely thing. He said, ‘Let’s have no tears, because Jerry wasn’t a man to shed tears over, nor was he a man to shed tears himself.’ And Oscar read this thing, and at the end he almost broke down himself. It was insane! The lovely things he said about Kern, what a darling man and all that, and I found tears coming down my cheeks. What for? There’d never been any great affection between us. We were just excellent collaborators, in a certain way.

“So much talent! When you hear a thing like ‘They Didn’t Believe Me,’ or some of the other tunes like ‘All the Things You Are,’ you forgive him anything.”