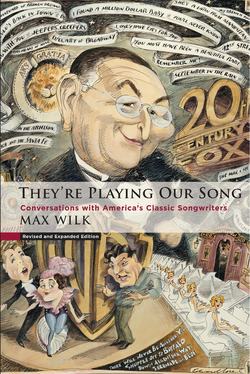

Читать книгу They're Playing Our Song - Max Wilk - Страница 19

“This Was a Real Nice Clambake” · Oscar Hammerstein II ·

ОглавлениеWHEN OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II wrote his first produced play in 1919, he was twenty-four years old. The play, The Light, was tried out in New Haven, Connecticut. “After the first act Dad knew he had a flop,” recalls his son, William. “In fact, later he always referred to it as ‘The Light That Failed.’ Well, he left the Shubert Theatre during the first intermission and went for a walk around the Yale campus. He wasn’t just going out for a depressed ramble; what he was doing was thinking what he would write for his next play.”

That sturdy resilience of young Oscar’s, the commingling of determination and forward motion, was to sustain him well for his next forty years as author, lyricist, and producer. But if he were still here to discuss his behavior in New Haven all those years ago, Hammerstein would probably dismiss it with a pragmatic, “Well, what else should a writer do, if he’s really a writer?”

For that is what Oscar Hammerstein was—a pro. From his earliest days on Broadway—writing books for operettas during the ’20s, setting lyrics to the music of Jerome Kern, Sigmund Romberg, Vincent Youmans, and Rudolph Friml—young Oscar always demonstrated that his talent was only one facet of his work, and that his meticulous application of it was what made the difference between the amateur and the pro. It is a lesson that appears to be lost on the current crop of slapdash songwriters, but they would do well to ponder it. Show Boat, which Hammerstein wrote with Kern in 1927, is running to packed houses in London as this is written, forty-six years after the fact. True, Jesus Christ Superstar is also having its run; but forty-five years from now, will they be reviving that? It’s a cinch that Show Boat will still be playing somewhere. “We certainly wouldn’t consider it a revival,” sniffed a prominent London theatrical manager. “We’ve always had a production of it around here. And we also had Hammerstein’s Desert Song doing quite nicely here in the West End, three years back.”

Oscar Hammerstein II

If his earlier work demonstrated staying power, then Mr. Hammerstein’s later years proved to be truly vintage ones. In the seventeen years of his collaboration with Richard Rodgers, the two men wrote and produced a series of musical shows for that verve, innovation, and sheer imaginative entertainment are truly something wonderful—Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, The Sound of Music. It was Cole Porter who, when asked to name the most profound changes in the musical-comedy field of his past forty years, replied simply, “Rodgers and Hammerstein.”

“Ockie,” as his friends always fondly called him, was more than a gifted author and lyricist. As Rodgers was to write in 1967, “His view of life was positive. He was a joiner, a leader, a man willing to do battle for whatever causes he believed in. He was not naïve. He knew full well that man is not all good and that nature is not all good; yet it was his sincere belief that someone had to keep reminding people of the vast amount of good things that there are in the world.”

In Hollywood, in the early 1930s, Hammerstein was among the first of the creative people living and working in that often frightened and mute community to take a positive stand against Nazism, both in Europe and here. Producers didn’t relish having songwriters take stands on political issues; that didn’t stop Hammerstein for a minute. During World War II he worked long and hard at various jobs designed to hasten V-J Day, and when the peace came, he dedicated himself to the idealistic cause of World Federalism.

Was there work to be done at the Dramatists Guild? Did neophyte television writers need help in forming a guild of their own? Oscar was always available, and never as a figurehead but as a worker, an adviser, a negotiator. A man with manifold pressures on him as a producer and writer, he was lavish with his valuable time.

Stephen Sondheim provides the most tangible evidence of Hammerstein’s consideration for others: “I first got into lyric-writing because when I was a child we moved to Pennsylvania, and among my mother’s friends were the Hammerstein family. Oscar Hammerstein gradually got me interested in the theatre, and I suppose most of it happened one fateful or memorable afternoon. He had urged me to write a musical for my school. With two classmates, I wrote a musical called By George. I thought it was pretty terrific, so I asked Oscar to read it—and I was arrogant enough to say to him, ‘Will you read it as if it were just a musical that crossed your desk as a producer? Pretend you don’t know me.’ He said okay and I went home that night with visions of being the first fifteen-year-old to have a show on Broadway. I knew he was going to love it.

“Oscar came over the next day and said, ‘Now, you really want me to treat this as if it were by somebody I don’t know?’ and I said, ‘Yes, please,’ and he said, ‘Well, in that case, it’s the worst thing I ever read in my life.’ He must have seen my lower lip tremble, and he followed up with, ‘I didn’t say it wasn’t talented, I said it was terrible, and if you want to know why it’s terrible, I’ll tell you.’ He started with the first stage direction and went all the way through the show for a whole afternoon, really treating it seriously. It was a seminar on the piece as though it were Long Day’s Journey into Night. Detail by detail, he told me how to structure songs, how to build them with a beginning and a development and an ending, according to his principles. I found out many years later that there are other ways to write songs, but he taught me, according to his own principles, how to introduce character, what relates a song to character, and so on. It was four hours of the most packed information. I dare say, at the risk of hyperbole, that I learned in that afternoon more than most people learn about songwriting in a lifetime…. He saw how interested I was in writing shows, so he outlined a course of study for me which I followed over the next six years, right through college.”

Such altruistic advice and counsel is not often available to a beginner; but generosity was always present in Hammerstein. No matter how much success he achieved, he retained a sense of perspective about his own gifts. One of the most lasting Hammerstein legends deals with the advertisement he took in Variety after the wildly successful opening of Oklahoma! in 1943. Remember, if you will, it was a season in which his version of Bizet’s opera, called Carmen Jones, was also selling out. In the annual holiday issue of Variety, in which successful show-business talents customarily trumpet their achievements to the rest of the fraternity, Hammerstein’s ad was modest, succinct, and made a very adroit point. In a quarter-page, his text read:

HOLIDAY GREETINGS

OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II

author of

Sunny River

(Six weeks at the St. James Theatre, New York)

Very Warm for May

(Seven weeks at the Alvin Theatre, New York)

Three Sisters

(Six weeks at the Drury Lane, London)

Ball at the Savoy

(Five weeks at the Drury Lane, London)

Free for All

(Three weeks at the Manhattan Theatre, New York)

I’VE DONE IT BEFORE AND I CAN DO IT AGAIN.

“That ad,” says William Hammerstein, “really expressed the way he felt, his sense of proportion. He was always afraid of reaching a stage of accomplishment where people expected too much from him … that he wouldn’t be able to deliver.”

There was hard-earned reason behind Hammerstein’s modesty. By the time he came to collaborate with Rodgers on Oklahoma! he was almost forty-eight years old, and behind him was a theatrical career that had produced equal parts of success and failure. In fact, Hammerstein’s story gives the lie to Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that “there are no second acts in American lives.” Hammerstein’s life followed the classic theatrical pattern of a well-made play: early success, adversity in the second act, and a triumphant third act with a smash finale.

The beginnings were as traditional as any show-biz story. If Oscar Hammerstein II wasn’t exactly born in a trunk, there was theatre all around his early youth. His grandfather and namesake was a hugely successful producer who brought Victor Herbert’s Naughty Marietta to the New York Theatre. Young Oscar’s father was William Hammerstein, who managed the Victoria Music Hall. How could any young man with such a background be anything but stage-struck? “He could quote all the old vaudeville acts from memory, verbatim, all his life,” says his son.

Hammerstein’s family sent him off to Columbia, and then to Columbia Law School, but he left there to go to work in the professional theatre. His uncle, Arthur Hammerstein, gave him a job as stage manager for a trio of Rudolph Friml musical operettas—You’re in Love, Sometime, and Tumble Inn. (Later Hammerstein was to provide lyrics for Rose-Marie, written by the same Friml, that astonishing gentleman who when past ninety years of age still composed music each and every day.)

After that initial debacle with his own play, Hammerstein wrote book and lyrics for his first musical show, Always You, with composer Herbert Stothart. It was 1920, and he was then twenty-five. Again at the suggestion of his uncle, he went to work with Otto Harbach on a show called Tickle Me. In the next few years Hammerstein and Harbach were to write Wildflower, Rose-Marie, Sunny, and The Desert Song together.

“Like most young writers,” he confessed years later, “I had a great eagerness to get words down on paper. He [Harbach] taught me to think a long time before actually writing. He taught me never to stop work on anything if you can think of one small improvement to make.”

Young Hammerstein developed rapidly into one of the most sought-after lyricists in the busy Broadway theatre of the 1920s. “Sigmund Romberg got me into the habit of working hard,” he wrote. “In our first collaboration, The Desert Song, I used to visit him. I remember one day bringing up a finished lyric to him. He played it over and said, ‘It fits.’ Then he turned to me and asked me, ‘What else have you got?’ I said that I didn’t have anything more, but I would go away and set another melody. He persuaded me to stay right there and write it while he was working on something else. He put me in another room with a pad and pencil. Afraid to come out empty-handed, I finished another refrain that afternoon. I have written many plays and pictures with Rommy and his highest praise has always been the same. ‘It fits.’ Disappointed at first at such limited approval, I learned that what he meant was not merely that the words fitted the notes, but that they matched the spirit of his music and that he thought they were fine.”

But it was with Jerome Kern that Hammerstein reached the absolute high-water mark of his early success. In 1927, when he was only thirty-two years old, he wrote the lyrics and the adaptation of Edna Ferber’s Show Boat. In that score are such indestructible works as “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” “Make Believe,” “Why Do I Love You?,” and, of course, “Ol’ Man River.”

It was during the preparation of that superb score that Hammerstein perpetrated a mild practical joke on his somewhat humorless collaborator, Kern. It was Kern’s working practice to write a melody, then hand it over to his current lyricist, and send his collaborator off to provide the words. One day he gave Hammerstein a lyrical ballad. The following day Hammerstein turned up at Kern’s studio and, without a word, handed Kern a piece of paper on which was written:

Cupid knows the way,

He’s the naked boy

Who can make you sway

To love’s own joy;

When he shoots his little ar-row,

He can thrill you to the mar-row …

Kern read through this mawkish set of rhymes with mounting dismay and horror. He was about to lose his temper when, with no change of expression, Hammerstein handed over a second set of lyrics, which read:

Why do I love you?

Why do you love me?

Why should there be two

Happy as we?

Can you see the why or wherefore

I should be the one you care for?

For once, so the legend goes, Mr. Kern was completely taken by surprise.

As to the origin of the classic “Ol’ Man River,” an interesting sidelight on how it came into being comes from Teddy Holmes, the general manager of Chappell, Ltd., the London firm which published the score of Show Boat. “I first produced here in London some years back,” he said. “Oscar said that during the preparation stages he felt a need for a unifying song, one that would express the feel of the Mississippi River, to tie the libretto together, so to speak. He discussed it with Jerry Kern, and Kern told him that he had too much else to do; at that particular moment he simply couldn’t contemplate writing another song. Now, as you know, if you listen to the score, there is that fast-paced banjo music that introduces the show boat Cotton Blossom in the first act; very bright and gay it is, too. Oscar said he went back to Kern later and said, ‘Why don’t you take that banjo music, which you’ve already written, and merely slow down the tempo?’ Kern took the suggestion and did exactly that—and there emerged that powerful theme for ‘Ol’ Man River.’ Listen to that banjo music and you’ll hear the ‘River’ strain imbedded in it. It was simply that Hammerstein heard it before Kern did.”1

“Kern would play pieces for me,” says Robert Russell Bennett, who worked closely with the two men, “and I’d say, ‘Is that the verse or the chorus?’ And Jerry used to die because I couldn’t tell which was which. One day he showed me this thing, and I put out a piano part to it. This one didn’t fall into the same category—that kind of piece Kern wrote that confused me—but it was a meandering sort of thing. It didn’t go much of anywhere when you just took the tune by itself. But the minute you got Oscar’s words to it—‘Tote dat barge, lift dat bale, git a little drunk an’ you land in jail’2—you had a real poet.”

A classic show-business story grew up about that same song. Mrs. Kern and Mrs. Hammerstein arrived at a party, and their hostess began to introduce them to her friends. “This is Mrs. Jerome Kern,” she announced. “Her husband wrote ‘Old Man River.’” “Not true,” said Mrs. Hammerstein promptly. “Mrs. Kern’s husband wrote dum-dum-dee-dah, dad um-dum-deedah. My husband wrote ‘Ol’ man river, dat ol’ man river!’”

Years later Hammerstein wrote about Kern and their collaboration. “During my several collaborations with Jerry, I was surprised at first to find him deeply concerned about details which I thought did not matter much when there were so many important problems to solve in connection with writing and producing a play. He proved to me, eventually, that while people may not take any particular notice of any one small effect, the over-all result of finickiness like his produces a polish which an audience appreciates.”

That “polish” in his own work was what Hammerstein sought throughout his career. Writing lyrics was hard, often agonizing work. His name for that work was “woodshedding.” Hour after hour he would stand at his desk, agonizing over the choice of the exact word, the perfect choice for the thought he wished to communicate. “Even when the songs were completed, they might not satisfy him,” says his son. “Take that final couplet of ‘All the Things You Are,’ from Very Warm for May, a song which everyone else considered near-perfect. Not Oscar. That next to last line—‘To know that moment divine’—he wanted to change the word ‘divine.’ It always bothered him.”

After the success of Show Boat there was The New Moon with Romberg, Rainbow with Vincent Youmans, and, with Kern, Sweet Adeline, a vehicle for Helen Morgan.

Hammerstein went out to Hollywood in 1930 to work with Sigmund Romberg on a film called Viennese Nights. In the very first years of the musical film, producers transferred stage productions directly to the screen with little, if any, adaptation to the film medium. Viennese Nights wasn’t very good, and Hammerstein went back to New York to do another show with Kern, The Cat and the Fiddle. There were beautiful songs in the score—“The Night Was Made for Love,” “Try to Forget”—and a Parisian background, but the show wasn’t as big a commercial success as the Kern tunes were to be. A year later the two men wrote Music in the Air, again with a European background. And again it was full of melodic treats— “I’ve Told Ev’ry Little Star,” “The Song Is You,” and others.

Hammerstein returned to Hollywood and spent most of his middle years there. The Broadway theatre in the ’30s was shrinking in size; there were also changes in the public’s tastes. For the price of a $2.20 ticket, the audiences there were beginning to demand more fact and less fantasy than before the Depression years. The era of the lush, opulent operetta was past; people who sought sweet escape from the daily, dreary realities of unemployment and soup kitchens and of stockbrokers leaping out of skyscraper windows were finding it for twenty-five cents in their neighborhood movie palaces.

“Everyone in those days was seduced by Hollywood,” comments Hammerstein’s son. “They went out there to make money. Oh, some of them may have had noble thoughts about the art of the film, but I don’t think in the early ’30s it had reached that point yet. As everyone else did, my father succumbed to a big salary. Jerry Kern went out first, and that may also have had a lot to do with it; they were always very close, not only in their work but socially.”

In 1934 the two men worked on a film version of their own Sweet Adeline. The picture was only a mild success; in the light of the new Busby Berkeley spectacles, it seemed a bit old-fashioned. “Perhaps he wouldn’t agree with this,” says his son, “but I don’t think Dad ever felt comfortable in the movie medium. He understood the stage—he had a fantastic instinct for timing, for climactic construction of a play, how to deal with a live audience, how to fashion an entertainment for the people sitting in a legitimate theatre. But I don’t think he ever really grasped the movie as a form.”

But if Hammerstein’s Hollywood years were far from his most creative, the life he led there was gemütlich enough. Money was no problem; his ASCAP royalties were more than enough for him to live on. The town was full of his contemporaries—Kern, Romberg, the Gershwins, Dorothy Fields, and actors, writers, wits, other displaced persons from New York, all of them attracted by those steady studio paychecks. It was the era of the swimming pool, Sundays by the tennis court, and smogless sun. One left the studio office and got home with plenty of time for a couple of sets.

And on weekends there were parties, and meetings of the Butterworth Athletic Club, named for the comedian Charles Butterworth, and consisting of such old friends as playwright Marc Connelly, songwriter Harry Ruby, and writer Charles Lederer. The members of the BAC met for drinks and tennis and for practical jokes.

There was nothing solemn about Hammerstein; he loved laughs as much as any of his friends did. “My voice had just changed,” recalls William. “My mother and father were due at dinner at Harry Ruby’s house one night, and my father suggested that I call up Harry after they’d left and I could impersonate him. I was to say, ‘Harry, this is Oscar. Can’t make it tonight. That’s all.’ Very brusque. And then I was to hang up. Well, I got my timing mixed up and called a few minutes too late. Ruby picked up the phone; I delivered my father’s dialogue, and then he said, ‘Not coming over, Oscar? That’s funny, because I can see you walking in my door!’”

Hammerstein and Lederer once fell into a mock feud, which they carried on for many months. When they met at parties, they would speak only through an intermediary. So successful was their performance that many people took their contretemps to be absolutely serious. “Then my father went off to London, to attend to some production over there, and he sent Lederer a cable which was the most cliché expression he could think of. It read: DEAR CHARLES ENGLAND IS ONE BIG BEAUTIFUL GARDEN. Charlie never acknowledged that cable. But about two years later he went to London, and one day my father received a cable from him which read: YES ISN’T IT.”

Kern and Hammerstein did produce one film score which earned them high marks. In High, Wide and Handsome were such hit songs as the title number, “Can I Forget You?,” and “The Folks Who Live on the Hill.” (The film was directed by Rouben Mamoulian, the same talented film-maker who was responsible for the earlier innovative Rodgers-and-Hart picture Love Me Tonight.) There were other pictures, less successful but often containing some work by Hammerstein that has lasted. From something called The Night Is Young there is “When I Grow Too Old to Dream,” set to Romberg’s music; and from another long-forgotten musical, starring Grace Moore, there is “I’ll Take Romance,” with music by Ben Oakland.

But creatively it was a semi-dry period. “He had nothing to worry about,” says his son. “Nothing—except if you were him. Money didn’t satisfy him. He worried about what was happening to him. With all his capacity for enjoying life, it simply wasn’t sufficient.”

In 1939 Max Gordon brought Kern and Hammerstein back to New York to do the musical show Very Warm for May. But despite a score which contains “All the Things You Are” and several other beautiful works, Hammerstein’s book faltered badly. (Broadway wags referred to it as “Very Cold for Max.”) And to add to his misfortunes, in the 1930s Hammerstein then had a couple of quick failures in London at the Drury Lane.

Again, from Robert Russell Bennett: “Oscar was a man who should have been a poet and never was because he had to write lyrics all his life. I think he was my closest and dearest friend in show business, all his years. One time when we were living in Paris, my wife and I, he and his wife came to see us. Oscar had had nothing but failures for quite some time, it seemed. At this dinner he said, ‘Dorothy and I are going to live in a little place here in France and she’s going to cook and take care of the household, and I’m going to write poetry.’

“And I told him then, ‘Nothing on earth could ever make me happier than to hear that, because you have poetry in you—you have great poems in you. But if you always stay in show business, where I’ve been, it’ll never come out.’ He said, ‘Well, it’s going to come out now. This is it.’ Then, a little bit later, along came Carmen Jones and then Oklahoma! and that was the end of Oscar as a poet. After that, he didn’t care much about writing a great poem any longer. He was satisfied to write those lyrics, which he made into works of art. But they have it all … they all sound as if it’s a poet trying to talk. It just burst out of him all the time!”

It may have been the fond memory of that evening with the Bennetts in Paris before the war that sparked Hammerstein to write one of his most poetic lyrics, to a melody of Kern’s, in 1941. The German Panzer divisions had occupied Paris, and Hammerstein wrote a song that expressed his dismay; “The Last Time I Saw Paris” was sentimental to a degree that caused tears. That the song would win the Academy Award for the best film song of that year (Metro had used it in Lady Be Good) was inevitable. Hammerstein had touched nerve ends with his writing; the song affected everyone. Even if you’d never been to Paris, you had to share his feelings.

His so-called “dry period” was over. Almost from that point on, audiences never ceased understanding exactly how Oscar Hammerstein felt. His lyrics told them, and the people responded. But to him it was never poetry, nor even poetic.

“Any professional author will scoff at the implication that he spends his time hoping and waiting for a magic spark to start him off,” he wrote in his book Lyrics. “There are few accidents of this kind in writing. A sudden beam of moonlight, or a thrush you have just heard, or a girl you have just kissed, or a beautiful view through your study window is seldom the source of an urge to put words on paper. Such pleasant experiences are likely to obstruct and delay a writer’s work…. Nobody waits to be inspired.”

He spent the next stage of his career—that triumphant third act with Richard Rodgers—back in the East, working mostly at his farm in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. There in his study was the captain’s desk which his friend Kern had given him, and at it, not seated but standing, he worked. Slowly, carefully, painstakingly. The dialogue for librettos he dictated into a machine; a secretary transcribed it, and then he revised. Lyrics were always done in longhand. What eventually was brought to Richard Rodgers to be se to music was always the result of hours of labor.

Even such a rollicking song as “This Was a Real Nice Clambake” (from Carousel), which the team adapted from Ferenc Molnár’s Liliom, involved long sessions of revision. Meticulous to the smallest detail, Hammerstein instructed his daughter to go to the local library and research all the recipes that were available for cooking clams and lobsters early-American style. (The background of Liliom had been changed from Europe to nineteenth-century New England.) The resultant meal, as the chorus of well-fed New Englanders lyrically describes it onstage, is not only a musical delight but an authentic recipe. For seafood lovers, it’s almost as good as a shore dinner.

His love songs are simple, clear, and uncomplicated. His attitude toward the female is perhaps idealized and highly irritating for Women’s Lib crusaders. “All his love songs are somewhat akin to ‘Something Wonderful,’ in which the woman in The King and I reveals herself as being completely dedicated to her man,” commented William Hammerstein, “or in ‘What’s the Use of Wond’rin?,’ where the girl says, ‘He’s your fella, and you love him, that’s all there is to that.’ Those attitudes may have been shaped by his own early years. His own mother died when he was twelve; to him she was the ideal, perfect. Most of his love songs come out of his feeling for her, I think.”

Stephen Sondheim insists that “Oscar was able to write about dreams and grass and stars because he believed in them.” And Richard Rodgers, who was his sole collaborator from Oklahoma! on, corroborates that analysis: “As far as his work with me was concerned, Oscar always wrote about the things that affected him deeply. What was truly remarkable was his never-ending ability to find new ways of revealing how he felt about three interrelated themes—nature, music, and love. In ‘Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,’ the first song we wrote together for Oklahoma!, Oscar described an idyllic summer day on a farm when ‘all the sounds of the earth are like music.’ In ‘It’s a Grand Night for Singing’3 he revealed that the things most likely to induce people to sing area warm, moonlit, starry night and the first thrill of falling in love. In ‘You Are Never Away’ he compared a girl with ‘the song that I sing,’ ‘the rainbow I chase,’ ‘a morning in spring,’ and ‘the star in the lace of a wild willow tree.’ In ‘Younger Than Springtime’ another girl is ‘warmer than the winds of June’ and ‘sweeter than music.’ In our last collaboration, The Sound of Music, just about everything Oscar felt about nature and music and love was summed up in the title song.

“Oscar believed that all too often people overlooked the wonders to be found in the simple pleasures of life. We even wrote two songs, ‘A Hundred Million Miracles’ and ‘My Favorite Things,’ in which Oscar enumerated some of them.”

Hammerstein never closed his eyes to the uglier side of life, however. One of his songs for South Pacific says it all about race prejudice. The young American officer who has fallen in love with a native girl is well aware of the color bars he will encounter when he sings “You’ve Got to Be Taught.” (“You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear…. It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear/You’ve got to be carefully taught.”)

Not only did he write on the subject; he participated. When author Pearl Buck opened her Welcome House, an adoption agency in Doylestown dedicated to placing infants of mixed racial backgrounds, the human backwash of the Korean War, in responsible homes, it was with Hammerstein’s considerable and constant assistance. And he was not afraid to stand up and allow himself to be counted. Playwright Hy Kraft, who was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee some twenty years ago and was an uncooperative witness, corroborates this in his book On My Way to the Theatre:

There’s a heart-warming P.S. to this Washington absurdity. There were two messages waiting for me in New York … one from Dorothy and Oscar Hammerstein. It wasn’t a message; it was a command to appear at dinner. After dinner Oscar had to catch The King and I, the current Rodgers-and-Hammerstein hit; he insisted that we meet later at Sardi’s. I was apprehensive about the Sardi’s visit. I knew that by the time we got to Sardi’s the final editions of the afternoon papers (we had more than one in 1952) and the bulldogs of the Times and the Trib would carry the review of my out-of-town performance, and I didn’t want to frighten those frightened people in show biz. In those days of McCarthy, Red Channels, Hedda Hopper, Pegler, Sokolsky, to be seen with an unfriendly witness was just one step away from the unemployment-insurance line. And in Sardi’s, yet! Of course, no committee or columnist could pull the rug from under Oscar’s standing in show biz, but the gesture of hosting a Fifth Amendment friend was a defiant commitment that raised plenty of eyebrows. And I might add that a number of my colleagues who acknowledged me that night in Oscar’s corroborative company turned away in years to come…. Oscar inscribed my copy of South Pacific, “For Hy. And why not? Oscar.” Every once in a while I read his lyric “You’ve Got to Be Taught to Hate.” The man who wrote that was my friend. I liked the world a lot better when he lived in it.

Oscar Hammerstein’s initial collaboration with Richard Rodgers, in 1943, confounded most of the Broadway sages. Nobody expected Away We Go (the original title of their adaptation of Lynn Riggs’ Green Grow the Lilacs) to be successful, least of all the audience that went up to New Haven. It is now a theatrical legend how, after the first-act curtain came down, various backers of the Theatre Guild’s production, to be retitled Oklahoma!, stood around the Shubert Theatre lobby, frantically selling off “pieces” of their investments.

But after that opening night, almost a quarter-century since his first disaster with The Light, Hammerstein did not go for a walk and start planning his next. This show would survive all the skeptics, the nay-sayers, and the disbelievers. Certainly there were changes to be made, but he believed in his and Rodgers’ work. Away went Oklahoma! to Boston, where it caught on, and then on to New York and thundering success. Those faint-hearted ex-backers in the New Haven intermission lost thousands of dollars of eventual profit through their lack of faith; the buyers of their “pieces,” even the smallest ones, became rich.

The two men were not only successful in creating their own works, but their partnership extended to the production of shows by others. As Dorothy Fields, who write the libretto of Annie Get Your Gun with her brother Herbert, points out, Hammerstein’s theatrical sense was quick to recognize the basic merit of casting Ethel Merman as Annie Oakley. He and Rodgers agreed that the logical choice for a composer would be someone else; they looked forward with keen pleasure to the prospect of bringing Hammerstein’s old friend and collaborator Jerome Kern back to the Broadway scene. Kern’s abrupt passing was a crushing personal blow to Hammerstein. Happily for audiences ever since, Irving Berlin agreed to take on the score.

The smashing success of Annie Get Your Gun seems all the more remarkable if one considers that Hammerstein, Rodgers, and Dorothy Fields were all top-ranking songwriters. Nowhere in the preparation of the show did any professional jealousy surface. “Both Dick and Oscar were marvelous producers,” says John Fearnley. “It was their continual ability to edit, to advise, to listen and then say, ‘No, that’s not quite right for this spot’—to counsel the other creative people without ever being in competition—that kept everything on the tracks.”

Hammerstein’s collaboration with Rodgers produced only two shows which could be considered less than absolute smash hits. Pipe Dream, based on John Steinbeck’s book Sweet Thursday, was a simple, joyful story about Steinbeck’s waterfront neighbors in his early days in California. It ran for a full season, but, despite a good score, it did not have the lasting qualities of South Pacific or the mass appeal of The Sound of Music. Nor was Me and Juliet vintage Rodgers-and-Hammerstein.

But their Allegro, which came earlier, in 1947, was a unique work. Reexamined a quarter-century later in the light of the current theatre, that show seems far ahead of its time. It is simply the musical biography of a young man, his birth, his childhood, and his arrival at what used to be referred to as man’s estate. “It was written out of his own heart and experience,” says his son. “He tried to say everything he’d learned about life. He had always been tremendously intrigued by his own childhood.”

There is a great deal of musical-comedy trail-breaking in Allegro. “I’ve Seen It Happen Before,” sung by the young man’s grandmother, deals with the universals of growing up. “One Foot, Other Foot” dramatizes the small triumph of the boy’s learning to walk in the wilderness of his own backyard. In the second act there is a sardonic comedy trio, “Money Isn’t Everything,” and an impatient, rejected sweetheart’s sad complaint, “The Gentleman Is a Dope.”

After the show closed, Hammerstein told an interviewer, “I wanted to write a large, universal story, and I think I overestimated the psychological ability of the audience to identify with the leading character.” But the years since Allegro was first produced have been more than kind to that work. Much of what Hammerstein wrote two decades ago has a definite kinship with the sort of free and open expression today’s songwriters are putting forward. Contemporary lyricists have long since left behind love and Dixie and moonlight bays; they deal now with war and peace, political subjects, leaving home—self-expression on a much more honest level. “As a matter of fact,” says Hammerstein’s son, “if my father were alive today, he would be trying very hard to understand the new writers, and to find out what they had in mind. People like Randy Newman and Dylan and Nilsson; he’d be listing to them carefully. He always understood that things inevitably changed. He welcomed that.”