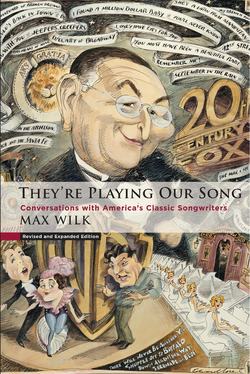

Читать книгу They're Playing Our Song - Max Wilk - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

“Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” · Lorenz Hart ·

ОглавлениеLONG AGO, in 1934, the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company of London’s Savoy Theatre crossed the Atlantic and took up temporary residence at the Martin Beck Theatre on 45th Street, there to perform a season of Gilbert-and-Sullivan light opera. My father, a dedicated Savoyard buff, led me to a succession of Saturday matinees.

One afternoon, during the intermission, he introduced me to Larry Hart, a diminutive black-haired gentleman. No pomposity about him: everyone—actors, musicians, even acquaintances of a moment’s duration—called him Larry.

What did Larry Hart do for a living?

He was a lyricist, my father explained later. A man who wrote the words to the music of a gentleman named Richard Rodgers.

“He writes pretty good stuff of his own,” I complained to my father. “What’s he doing here every week, listening to W. S. Gilbert’s?”

“Homework,” said my father. “You could say he was taking a refresher course.”

I had no idea what he meant by that remark until some years later, at a summer-stock playhouse in Cohasset, Massachusetts, when I listened to Larry Hart talk. He was erudite, witty, charming; his head was crammed with fact and fancy, reflecting the remarkable scope of his learning. To sing or to read his lyrics is to encounter an endless succession of exotic references, gracefully turned into rhyme. As the afternoon wore on, he had quite a few drinks and his speech became somewhat slurred. But Larry’s mind never went under the influence.

Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart

I reminded him then of his steady attendance at those D’Oyly Carte Saturday matinees, and of my father’s explanation for his presence there at the Martin Beck.

“Your old man was absolutely right!” said Larry. “I was there to study! Old man Gilbert was the greatest lyricist who ever turned a rhyme!”

Hart was born in 1895, descended on his father’s side from Heinrich Heine. He was a voracious reader with an early-developed taste for the theatre. He went to Columbia (the alma mater of many others who went into show business, including Rodgers and Hammerstein) but left to work for the Shuberts.

A remarkable, mercurial man, Larry Hart.

“He was always skipping and bouncing,” Oscar Hammerstein once recalled. “In all the time I knew him, I never saw him walk slowly. I never saw his face in repose. I never heard him chuckle quietly. He laughed loudly and easily at other people’s jokes, and at his own, too. His large eyes danced and his head would wag. He was alert and dynamic.”

Recalling their first meeting, Mr. Rodgers said, “He was violent on the subject of rhyming in songs, feeling that the public was capable of understanding better things than the current monosyllabic juxtaposition of ‘slush’ and ‘mush.’ It made great good sense, and I was enchanted by this little man and his ideas. I left Hart’s house having acquired in one afternoon a career, a partner, a best friend, and a source of permanent irritation.”

The first Rodgers-and-Hart song, written before Rodgers was even a student at Columbia, was “Any Old Place with You,” which Lew Fields added to the score of a musical in which he was appearing on Broadway, A Lonely Romeo.

Rodgers wrote about their friendship and collaboration for the Dramatists Guild Quarterly:

In many ways, a song-writing partnership is like a marriage. Apart from just liking each other, a lyricist and a composer should be able to spend long periods of time together—around the clock if need be—without getting on each other’s nerves. Their goals, outlooks, and basic philosophies should be similar. They should have strong convictions, but no man should ever insist that his way alone is the right way. A member of a team should even be so in tune with his partner’s work habits that he must be almost able to anticipate the other’s next move. In short, the men should work together in such close harmony that the song they create is accepted as a spontaneous emotional expression emanating from a single source, with both words and music mutually dependent in achieving the desired effect.

I’ve been lucky. During most of my career I’ve had only two partners. Lorenz Hart and I worked together for twenty-five years; Oscar Hammerstein II and I were partners for over eighteen. Each man was totally different in appearance, work habits, personality, and practically anything else you can think of. Yet each was a genius at his own craft, and each, during our association, was the closest friend I had.

I met Oscar before I met Larry. I was twelve and he was nineteen when my older brother Mortimer, a fraternity brother of Oscar’s, took me backstage to meet him after a performance of a Columbia Varsity Show. Oscar played the comic lead in the production, and meeting this worldly college junior was pretty heady stuff for a stage-struck kid.

I met Larry about four years later. I was still in high school at the time, but I had already begun writing songs for amateur shows, and I was determined even then to make composing my life’s work. Although I had written the words to some of my songs, I was anxious to team up with a full-fledged lyricist. A mutual friend, Philip Leavitt, was the matchmaker who introduced us one Sunday afternoon at Larry’s house. I liked what Larry had written, and apparently he liked my music. But most important, we found in each other the kind of person we had been looking for in a partner—our ideas and aims were so much alike that we just sensed that this was it. From that day on, until I wrote Oklahoma! with Oscar, the team of Rodgers and Hart was an almost exclusive partnership.

Larry Hart, as almost anyone will agree, was a genius at lyric construction, at rhyming, at finding the offbeat way of expressing himself. He had a somewhat sardonic view of the world that can be found occasionally in his love songs and in his satirical numbers. But Larry was also a kind, gentle, generous little guy, and these traits too may be found in some of his memorable lyrics. Working with him, however, did present problems, since he had to be literally trapped into putting pen on paper—and then only after hearing a melody that stimulated him.

The great thing about Larry was that he was always growing— creatively, if not physically. He was fascinated by the various techniques of rhyming, such as polysyllabic rhymes, interior rhymes, masculine and feminine rhymes, and the trick of rhyming one word with only part of another. Who else could have come up with the line, “Beans could get no keener re-/Ception in a beanery,” as he did in “Mountain Greenery”?1 Or “Hear me holler/I choose a/Sweet Lolla-/Paloosa/In thee” in “Thou Swell”? Or “I’m wild again/Beguiled again/A whimpering, simpering child again,” in “Bewitched”?

Yet Larry could also write simply and poetically. “My Heart Stood Still,”2 for example, expressed so movingly the power of “that unfelt clasp of hand,” and did it in a refrain consisting almost entirely of monosyllables. Larry was intrigued by almost every facet of human emotion. In “Where or When” he dared take up the physic phenomenon of a person convinced that he has known someone before, even though the two people are meeting for the first time. As the years went on, there was an increasingly rueful quality in some of Larry’s lyrics that gave them a very personal connotation. I am referring to such plaints as “Nobody’s Heart Belongs to Me” (from By Jupiter), with its feigned indifference to love, and “Spring Is Here,” a confession of one whose attitude about the season is colored by his feeling of being unloved. It should not be overlooked, however, that Larry was also attracted to the simple life. Remember his paean to rustic charms in “There’s a Small Hotel,”3 or to “our blue room far away upstairs.” Or his attitude in “My Romance,” in which he dismissed as unnecessary all the conventional romantic props when two people find themselves really in love.

Eventually Rodgers and Hart were to form a working partnership with Herbert Fields, the son of the great Lew. Dorothy Fields, later a collaborator with her brother Herbert, grew up with the young triumvirate in her home. “Upstairs on the top floor of the house on 90th Street they were all working hard on musical shows,” she recalled. “After Columbia Varsity Shows they had formed a combination. Herb was to do the book—and he was obsessed with the necessity of a strong book (as I was to be later), Dick the music, and Lorenz the lyrics. They had bright, fresh, wonderful ideas, but no one gave them an ear—least of all the famous actor-producer [Fields père] sitting downstairs in his library on the second floor.

“Fields, Rodgers, and Hart peddled their wares to diverse producers who fixed a baleful eye upon brother Herbert and said, ‘If you guys are as good as you think you are, how come your father, Mr. Fields, isn’t interested in producing your show?’”

Lew Fields came from an earlier era in which musical comedy meant what it said—a certain amount of music and a double helping of laughs. A coherent libretto? A book show? Miss Fields said, “Pop would say, ‘What book? In a musical, give them gags, blackouts, belly laughs, great performers, and great performances: that’s what they’ve come for. They don’t come to a musical comedy for a story.’ But he changed, and when Pop changed, he changed all the way. Herb, Dick, and Larry had to come through with two enormously successful Garrick Gaieties produced by the Theatre Guild, and then a charming play, Dearest Enemy, before Pop began to believe that the kids had something there.”

The first edition of The Garrick Gaieties was scheduled to have only two performances, on a Sunday in May 1925. Its ostensible purpose was to give the young talent of the Theatre Guild a showcase, and also to raise money to purchase tapestries for the theatre on 52nd Street that the Guild was building. What the show actually did was to launch Rodgers and Hart into a songwriting orbit that was to last until Hart’s death in 1943.

Years later, so the story goes, Rodgers and Hart attended a performance at the Guild Theatre. Rodgers nudged Hart and pointed at the tapestries that decorated the walls. “We’re responsible for those,” he murmured. Hart shook his head. “They’re responsible for us,” he said.

Out of the score of that first revue came “Manhattan” and “Romantic You and Sentimental Me.” That fall, in Dearest Enemy, the young team had another hit, “Here in My Arms.” And there followed the show which Lew Fields produced, The Girl Friend.

“It had a lively story and a stunning score,” remembers Dorothy Fields. “And those boys [Rodgers, Hart, and Fields] were really hell on ‘book.’ During rehearsals Pop dusted off the old ledger and came up with some blockbusters, but the boys wouldn’t accept one joke. Nothing went into that show that didn’t go along with the story!”

More than four decades later the strength of their score survives remarkably well. One of the show’s hits was “Blue Room,” and another, the catchy and carefree “The Girl Friend.”

“Only one thing remained constant in Larry’s approach to his job,” Dick Rodgers was to remark. “He hated doing it and loved when it was done. I saw him write a sparkling stanza to ‘The Girl Friend’ in a hot, smelly rehearsal hall, with chorus girls pounding out jazz time and principals shouting out their lines. In half an hour he fashioned something with so many interior rhymes, so many tricky phrases, and so many healthy chuckles in it, that I just couldn’t believe he had written it in one evening.”

Under the beneficent production auspices of Lew Fields, the Herbert Fields-Rodgers-Hart partnership was to evolve three more successful musicals: Peggy-Ann, with its wistful ballad, “Where’s That Rainbow?,” A Connecticut Yankee, and Present Arms.

The pleasures of the score of A Connecticut Yankee cannot be put into words; such works were meant to be listened to, hummed and sung. What is there to say about “Thou Swell” that Larry Hart has not already set down in his gay, intricate lyric? “I Feel at Home with You,” “On a Desert Island with Thee,” “My Heart Stood Still”—the eye reads the titles, the brain evokes the strains of the music happily melded with the words, everything floods back into the mind, and if you’re a Rodgers-and-Hart fan, how can you help but sing?

In Present Arms was “You Took Advantage of Me.” In Spring Is Here, “With a Song in My Heart.” In another show of the same period, Heads Up, there was the beautiful torch song “A Ship Without a Sail.” A couple of years later, in America’s Sweetheart, there were two deft love songs called “I’ve Got Five Dollars” and “We’ll Be the Same,” in which Hart maintained, “There may be thirteen months in the year/Nations may disappear/Hiho, we’ll be here and we’ll be the same.”

Although neither of the two men enjoyed their Hollywood experiences, they did some remarkably advanced work for the early cinema musicals. They wrote a sparkling score for Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald in the film Love Me Tonight, providing “Mimi,” “Lover,”4 and a title song. But some of their most inventive work was done for a film that was far from successful, an original musical called Hallelujah, I’m a Bum, which starred Al Jolson.

Back on their home ground, Broadway, they did the score for Jumbo and serenaded the audience with “Little Girl Blue,” “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World,” and “My Romance.” Then came On Your Toes, with “There’s a Small Hotel,” “It’s Got to Be Love,” and a song whose title seems to express a great deal about Larry Hart’s attitude toward life, “Glad to Be Unhappy.”

The man who wrote all these brilliant lyrics—who could range from the beautiful ballad “Falling in Love with Love” (from The Boys from Syracuse)5 to the sardonic ripostes of “The Lady Is a Tramp” (Babes in Arms), who could craft all those acid-edged rhymes that mark the score of Pal Joey and then write a paean to his beloved, “Wait Till You See Her” (By Jupiter)—was far from a simple personality. In his work he never ceased to seek out new and more inventive ways to express himself. Back in 1938 Time magazine’s theatre critic wrote, “As Rodgers and Hart see it, what was killing musicomedy was its sameness, its tameness, its eternal rhyming of June with moon. They decided it was not enough to be just good at the job; they had to be constantly different also. The one possible formula was, Don’t have a formula; the one rule for success, Don’t follow it up.”

But evidently the success of Hart’s work wasn’t enough. “He needed laughter the way some men need praise,” commented David Ewen in his biography of Rodgers. “A carefully timed wisecrack, a well-told joke, a neatly turned pun, a skillfully perpetrated prank—these were the meat and drink of his soul.”

The success of the Rodgers-and-Hart collaboration—and it was remarkably constant during the late 1930s and early 1940s—never seemed to answer Hart’s emotional needs. His humor, which bubbled out into brilliant rhyme, covered a deep-seated unhappiness. “Larry was a night person,” says a friend who knew him well. “He never seemed to have any place to go. He’d hang around Louie Bergin’s tavern on 45th Street, where actors and show people always congregated after the show, stay there until closing time, buying everybody drinks, paying no attention to what it cost. All he wanted to do was to talk. He’d haul out a big wad of bills and spend it without a second thought. And remember, back in those days his weekly royalties would be considered a huge sum even by today’s standards.” Once Hart told Ted Fetter, another talented lyricist, “I can’t believe I make so much money—it’s completely disproportionate for the work I do to earn it.”

Robert Russell Bennett recalls another occasion: “We were having supper after the theatre one time in London. Simpson’s Restaurant, I think it was. I was talking to Larry about writing lyrics, and I mentioned one of his ballads, and I asked him, ‘Larry, what inspired you to write such a lovely lyric?’ And Larry said, ‘Oh, Russ, when I write the lyric, the only time I’m inspired … pencil in my hand and a piece of paper in front of me,’ he said, ‘that’s the inspiration.’”

Such self-effacing statements are astonishing when one contemplates the scope of his work; it represents a dazzling display of virtuosity. Think of the cynical boy-girl duet “I Wish I Were in Love Again,” in which he penned “When love congeals/The air reveals/The faint aroma of performing seals.” Listen to the dazzling score of The Boys from Syracuse, in which the first eight or nine minutes of intricate Shakespearian exposition is brilliantly distilled for the audience in Hart’s rhymes and Rodgers’ music. Treat yourself to all those lightly mocking works in which he contemplated the various aspects of love—“This Can’t Be Love,” I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” “My Romance,” “Love Never Went to College.” And should your taste run to social comment, listen to his words for songs like “Too Good for the Average Man,” and the song in which the pseudo-intellectual strip-teaser in Pal Joey ruminates on the intellectual world while removing her clothes, “Zip.” (“Zip! Walter Lippmann wasn’t brilliant today/Lip! Will Saroyan ever write a great play?/Zip! I was reading Schopenhauer last night/Zip! And I think that Schopenhauer was right.”)

Toward the end of his life Hart was increasingly depressed and moody. The score for By Jupiter in 1942 was brilliant, but his propensity for work was diminishing. Perhaps his sense of loneliness is somewhat prophetically expressed in his own lyric, written for the very last show he worked on, a revival of A Connecticut Yankee in 1943. His partner, Dick Rodgers, was already discussing a collaboration with Oscar Hammerstein on a musical version of Lynn Riggs’ Green Grow the Lilacs. It was a project Hart had turned down. He didn’t feel it was his sort of show; Oklahoma and the Southwestern scene weren’t his turf. Where Hart saw the irony, the sharp contradictions of life, Hammerstein saw the optimistic side. But Hart did contribute to the Connecticut Yankee revival. He wrote a magnificent song for Vivienne Segal to sing—“To Keep My Love Alive”—in which the lady described in a superb procession of couplets how she had done away with many of her past lovers, medieval-style. And then he wrote a gentle ballad called “Can’t You Do a Friend a Favor?” in which he penned a verse, the words of which may embody his final self-analysis:

You can count your friends on the fingers of your hand,

If you’re lucky, you have two.

On the opening night of A Connecticut Yankee, Hart stood up throughout the performance in the back of the theatre, and when the curtain fell— the revival was again a success—he wandered out into the cold November night. Two days later he was found unconscious, with pneumonia, in a hotel room. He died three days after, at the age of forty-eight.

But Larry Hart would have been the first to object to finishing any discussion of his career on such a downbeat note. Since his stage works invariably finished with a joyful strain, he would undoubtedly prefer us to chortle over an incident that took place when On Your Toes was running on Broadway.

In the first act of the show, which starred Ray Bolger as a vaudeville hoofer who took up ballet, there was an opulent ballet spoof, staged by George Balanchine, called “The Princess Zenobia,” complete with slaves, harem trappings, and broadly satirized echoes of the Far East. At a given point in the ballet, the chorus boys, dressed as Nubian slaves, made a tumultuous entrance to Rodgers’ music.

Larry Hart’s agent, a legendary Broadway character named “Doc” Bender, spent many evenings hanging around backstage, chatting and passing jokes back and forth with the chorus boys.

Dick Rodgers, who was (and is) a stickler for keeping up the level of a show’s performance after opening night, noticed that on successive evenings the entrance of the Nubian slaves was happening later and later, to a point where it disrupted the entire number. Upon investigating, Rodgers discovered that “Doc” Bender’s presence backstage was responsible. Irritated, Rodgers called his partner to complain. “It’s up to you to see to it that Bender stays away, at least until after the curtain comes down!” he instructed.

Without hesitating, Hart ad-libbed (to the tune of “There’s a Small Hotel,” the hit song from the team’s score):

Looking through the window, you

Can see six slaves and Bender.

Bender’s on the ender—

Lucky Bender.

It’s a safe guess that old W. S. Gilbert would have laughed.