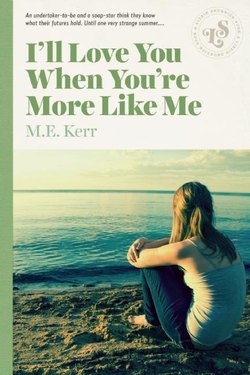

Читать книгу I'll Love You When You're More Like Me - M.E. Kerr - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5. Wallace Witherspoon, Jr.

I never liked bringing home kids from school because of the way they got quiet once they were in the house. I always had the feeling they couldn’t wait to talk about it once they got out of there. (“They’ve got three rooms in front for the corpses!” et cetera.) But Charlie Gilhooley was the exception. He was another bookworm, another receiver of A pluses from Mr. Sponzini, and almost as big an authority on Seaville and its history as old Mr. Sigh, who lived with his sister and wore knicker suits year round.

“Ramps instead of stairs!” Charlie exclaimed the first time I ever dragged him home from the library with me. “Of course! To wheel the bodies around! Makes perfect sense!” Charlie was slightly on the enthusiastic side about nearly everything—that was his way—but it was better than just clamming up and pretending my house wasn’t any different from anybody else’s.

Charlie wanted to know everything there was to know. He wanted to know more than I wanted to know about the Witherspoon Funeral Home, and I’d have to tell him I didn’t know the answers to half his questions because I had this deal with my father: I didn’t have to take an active interest in the business until I was out of high school. Charlie’d ask, “How can you not want to know?” “I’ll never want to know,” I’d tell him, “even after I know.”

Charlie was sixteen when he started telling a select group of friends and family that he believed he preferred boys to girls. The news shouldn’t have come as a surprise to anyone who knew Charlie even slightly. But honesty has its own rewards: ostracism and disgrace. Even Easy Ethel Lingerman, whom Charlie dated because he loved to dance with her—Easy Ethel always knew all the latest dances—even Easy Ethel was ordered by her grandmother to stop having anything to do with Charlie.

My own deal with Charlie was don’t you unload your emotional problems on me, and I won’t unload mine on you. We shook hands on the pact and never paid any attention to it. I went through a lot of Charlie’s crushes with him, on everyone from Bulldog Shorr, captain of our school football team, to Legs Youngerhouse, a tennis coach over at the Hadefield Club. Charlie, in turn, had to hear and hear and hear about Lauralei Rabinowitz. (“How can you be so turned on to someone with a name like that!” Charlie would complain.)

The same week Charlie made his brave or compulsive confession, depending on how you look at running around a small town a declared freak, Mrs. Gilhooley visited Father Leogrande at Holy Family Church and tried to arrange for an exorcist to go to work on Charlie. Charlie’s father, a round-the-clock, large-bellied beer drinker, who drove an oil truck for a living and in his spare time killed every animal he could get a license to shoot, trap or hook in the throat, practiced his own form of spirit routing on Charlie by breaking his nose. It was a a blessing in disguise, Charlie needed at least one feature that was just slighty off, to look believable. The nose gave him that credibility, but people still always looked twice at Charlie, even before he spoke or walked. To use my sister’s favorite, and maybe only, conversational adjective, Charlie’s good looks are unreal.

Mrs. Gilhooley’s idea of dinner is a paper plate swimming in SpaghettiOs, with a Del Monte peach half in heavy syrup thrown in for variety. The Gilhooleys live in a ranch house on half an acre up in Inscape, near the bay, and Mr. Gilhooley has crammed the yard with old cars, front seats of old cars, assorted old tires, a boat which no longer floats, rusted lawn mowers and broken garden tools, and an American flag, on a pole with the paint peeling off it, which has been raised one time only and never lowered. It flies on sunny days, in hurricanes and through the Christmas snows, a tattered red-white-and-blue thing that must resemble the rag Francis Scott Key spotted after the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

I won’t describe the inside of the Gilhooley house. It’s enough to say that it was one of life’s little miracles that Charlie came out of that pit every day looking more like someone leaving one of the dorms of the Groton School for boys than someone leaving something that long ago should have been condemned by the Sanity and Sanitation Committee.

I think Charlie regrets having emerged from his closet, even though long before he did he was called all the same names, anyway. Charlie told me once: “You can make straight A’s and A+ ’s for ten years of school, and on one afternoon, in a weak moment, confess you think you’re gay. What do you think you’ll be remembered as thereafter? Not the straight-A student.”

My father has an assortment of names for Charlie: limp wrist; weak sister; flying saucer; fruitstand; thweetheart; fairy tale; cupcake, on and on. He never calls Charlie those names to his face, naturally; to Charlie’s face, my father is always supercourteous and almost convivial. After all, everybody’s going to die someday, including the Gilhooleys; why make their only son uncomfortable and throw business to Annan Funeral Home?

Whenever my mother told me we were having corned beef and cabbage for dinner, I usually asked Charlie over that night. It was his very favorite meal. He crooned and swooned over the anticipation of it every time, just as he was doing that night in my bedroom.

“Oh, and the way your mother does the cabbage,” he was saying, “not overdone, just crisp and with some green still in it, butter melting off it—” et cetera. Charlie can do a whole number on a quarter of a head of cabbage.

I was sitting there fondling the gold cuff bracelet, trying to figure out what to do with it, since there was no summer phone listing, no listing at all for Sabra St. Amour. She probably had an unlisted number; a lot of the summer people from New York City did.

I was also watching Charlie and wishing I was his height (6’3½”) and had his deep blue eyes and thick golden hair. The Lord gives and the Lord takes. I wouldn’t like Charlie’s high-pitched, sibilant voice, nor his strange, small-stepped, loping walk. When you first see Charlie walk, you think he’s into an impersonation of someone, or doing a bit of some kind, but he’s not. The walk is for real.

Charlie says ever since the movies and television have been showing great, big, tough gays, to get away from the stereotype effeminates, he’s been worse off than ever before. “Now I’m supposed to live up to some kind of big butch standard, where I can Indian-wrestle anyone in the bar to the floor, or produce sons, or lift five-hundred pound weights over my head without my legs breaking.”

“‘The media is trying to make it easier for your kind,” I argued back.

“They’re trying to make it easier for those of my kind who most resemble them,” Charlie said.

My sister, A. E., came into my room just as Charlie was finishing his drooling over the cabbage with the butter melting on top. She said, “Forget it. The menu’s changed.”