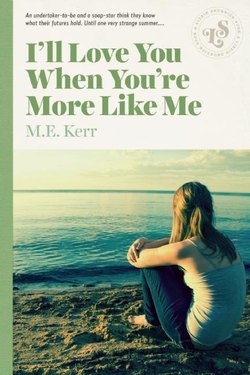

Читать книгу I'll Love You When You're More Like Me - M.E. Kerr - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3. Wallace Witherspoon, Jr.

Instead of underwear in the summer, I always wear a pair of trunks under my jeans so I can take a swim at one of Seaville’s beaches if I feel like it. This drives my mother up the walls. My mother says it’s no way for the son of a funeral director to behave. Funeral directors’ children, according to my mother, must lead exemplary lives because of the very delicate nature of the profession. Our home is supposed to be the sort of home one wants to see their loved ones resting in “at the end of the long journey”—to use another of my mother’s euphemisms for death.

If you want to know anything at all about the protocol of running a funeral home, don’t ask my father, ask my mother. I think my mother’s the world’s foremost authority on the dos and don’ts of funeral-home life. Do keep all the shades in the front of the house at the exact same level. Don’t sit around in any front rooms watching television with the drapes open at night. Do keep “the coach” (the polite word for the hearse) in the garage with the garage doors down, at all times. Don’t just throw out old “floral tributes” in the trash, but stuff them into a Hefty Lawn and Leaf Bag so they are not recognizable as old flowers. On and on and on.

Every time I slip out of my trousers on the beach, I hear my mother’s voice in my mind crying, “Wal-ly! Oh, no!”

That hot August afternoon after I left Harriet’s, I left my pants and shirt and sneaks in a ball on the sand, and walked down to the water’s edge. The tide was coming in, and Lunch Montgomery, this old blind-in-one-eye, black-and-white hound dog, was running around in the surf barking. That meant Monty Montgomery had to be around somewhere, a prospect I didn’t welcome.

A few afternoons a week I worked for Monty in the store he and his wife owned, called Current Events. Monty sold newspapers and magazines, greeting cards, games and office supplies. He also sold T-shirts, standard ones already printed up, or the kind you could have anything you wanted printed on them. I was the printer, the poor slob who fitted the letters on the shirt and then stream pressed them into it. For this I got $2.60 an hour. The fair thing would have been for Monty and his wife to pay me about triple that, since I acted as their go-between. I don’t think they even talked when I wasn’t around. When I was there, Monty would say things to me like “Ask her why she orders twenty copies of Town & Country every month when we only sell three.” Martha, his wife, would come back with something like “Ask him if he’s heard that slave labor is against the law, or hasn’t that rumor spread to the beach where he spends all his time?”

Monty would say, “Ask her if she imagines my idea of the perfect life is working twelve hours a day in some hick store selling Sugar Daddies to runny-nosed kids?”

Martha would say, “Ask him when he’s ever worked twelve hours a day anywhere.”

“Ask her,” Monty would say, “if she thinks I got an education at Yale to stand here marking half the TV Guides New England and half Manhattan.”

“Ask him,” Martha would respond, “if he could have done better with his striking Yale education why he didn’t.”

They were your real all-American happily married couple, the kind you saw eating out in restaurants across the table from each other without saying anything but “Pass the salt,” or “Where’s the butter?” Silently We Eat Our Sizzling Sirloins, Hating Each Other’s Guts Department.

Lunch was really Martha’s mutt, but he followed Monty whenever Monty took off for the beach, which was a lot in the summer. Monty would swim out and Lunch would stand in the surf barking, as though he was a scolding stand-in for Martha.

Lunch’s blind eye was a light blue color; the other eye was black.

“Did anyone ever tell you you were hilarious looking?” I asked him.

The dog ignored me. Sure enough, there was Monty out in the ocean, riding the waves on a surfboard.

The only other person around was this blond girl, sitting on a towel. Everyone else was in the area where the lifeguards were, about a half mile down the beach.

I was standing there wondering what the chances were of going in the water without having to strike up a conversation with Monty.

Monty’s conversations begin something like this: “Hi there, Wither-Away, seen any good corpses lately?”

A variation: “Hi there, Withering Heights, I’m dying to see you.”

Then he’d hold his sides laughing, give me a cuff to my ear, and start in on my relationship with Harriet.

“You going to marry her?” he’d ask. “Lots of luck, fellow. I married my high-school sweetheart and it’s been downhill ever since.”

I wasn’t in a mood for Monty ever; that day, I really wasn’t.

I walked down the beach away from him, past the girl on the towel.

Then I heard her calling me. “Hey! Hey, there! Hey!”

I turned around and she was standing, taller than I was, this long-legged, slender, pale girl with large green eyes and a tiny mouth. She wore a black bathing suit and a large gold cuff bracelet. She looked as though she’d been hospitalized all summer, or imprisoned—kept somewhere where the sun never shined.

“I came down here with cigarettes and no matches,” she said, walking up to me. “I don’t know how I could be so dumb.”

“I don’t, either,” I said.

“Well do you have a match?”

“It isn’t dumb to forget your matches,” I said. “It’s dumb to smoke.” I stood there trying to figure out why there was something vaguely familiar about her, even her voice.

“Thanks an awful lot,” she said. “I had the feeling I could count on you the minute I saw you.” She was holding a package of gold Merits in her hand.

“Do you think you can count on the tobacco companies to look out for you?” I said.

“I don’t need someone to look out for me,” she said, “I need a match.”

She started to walk back to her towel. I didn’t want her to go. It wasn’t that I needed another girl who towered over me in my life again, but I had this really flaky feeling that I’d spent time with her. Déjà vu or something. My father and mother had a song when they were courting called “Where or When.” My mother liked to play it on the piano and sing along. It was about meeting someone and feeling you’d stood that way with them and talked before, and looked at each other the same way before. That was sort of the feeling I had with this girl.

I tried to stall her. “A long time ago,” I said, “cigarettes had simple names: Kools, Camels, Lucky Strikes, Old Golds.”

“They’re still in existence,” she said. “Where have you been?”

“Where have you been?” I said. “You’re the whitest girl on the beach.”

“I was in an insane asylum,” she said.

“You’d have to be a little crazy to let the tobacco companies manipulate you,” I said. “Why do you think they’d name a cigarette something like Merit? Merit’s supposed to mean excellence, value, reward. What’s so excellent, valuable and rewarding about having cancer?”

“I’ve heard of coming to the beach for some sun,” she said, “for a swim, for a walk. I never heard of coming to the beach for a lecture.”

“Think of the names of the new cigarettes,” I said, realizing I’d stumbled on an idea that wasn’t half bad. “Vantage—as in advantage; True; More; Now. The cigarette companies are using hard sell, because they’re scared that the public will wise up to the fact they’re selling poison.” Not bad at all, Witherspoon. I complimented myself. “Live for the moment because you won’t live long. Get More. Be True to your filthy habit.”

“Just say you don’t have a match,” she said.

At that moment, Lunch came skidding in between us, chasing a rubber duck that had been tossed in our direction. He was wet and she let out a scream, while Monty came jogging up to us with one of his sadistic grins. He had on a T-shirt with YALE written across it. He had his usual ingratiating opener.

“Hi there, Wither Up And Die. Cheating on Harriet?”

Then he took a look at the girl and did a double take.

Monty is not subtle in any way. He is this big palooka who lifts weights every morning and measures his chest size once a week. He is a wraparound baldie, who uses the last few strands of hair he has left to wrap around his already-denuded crown. When he does a double take, his whole body participates. His shoulders swing, his neck jerks, his hands shoot up to his hips with his elbows bent outward, his mouth drops open and his eyes bulge.

“Why, you’re Sabra St. Amour,” he croaked.

“That’s right,” I found myself agreeing aloud in stunned amazement. “That’s who you are.”

That’s who she was, not nearly as beautiful as she came across on the big boob tube, but it was Sabra St. Amour, ail right: the soft long blond hair and sea-colored eyes, the husky voice (not so sensual sounding when you realized it was caused by clogged lungs), the small, slanted smile.

I said, “But I just saw you on the tube,” and stood there like any star-struck jerk, incredulous, and staring at her.

“That was on tape,” she said.

Monty stuck out one of the elephant paws he has for hands and said, “I’m Montgomery Montgomery. How do you do.”

She winced in pain as he crushed her bones and pumped her arm up and down. “How do you do,” she said.

I managed, “I’m Wally Witherspoon.”

“Hey, Sabra St. Amour!” said Monty. “How about that?”

Lunch began to bark furiously, standing there like Martha complaining about the whole idea of Monty striking up a conversation with a star.

“Shut up, Lunch!” Monty commanded. Lunch barked all the harder.

“Well.” Monty tried talking above the noise. “Tell me more!”

Sabra St. Amour made a face as though she always got that wherever she went, and Lunch persisted, only then he began to jump up on Monty. Monty would shove him back, and Lunch would charge with more gusto, until Lunch was actually snarling, and Monty was really giving it to him with his knee in Lunch’s neck.

“Don’t hurt him!” Sabra exclaimed when Lunch let out a yowl of pain.

“Dogs aren’t supposed to be on the beach.” I put in my two cents.

“What are you doing here then?” Monty asked me, but he finally had to give up and jog away so Lunch would follow and desist.

Monty called over his shoulder, “Better not let Harriet catch you, Wither-Away!”

“Who’s Harriet?” Sabra St. Amour asked, when we could hear each other again.

“Just some fellow I know,” I said.

She laughed.

“Does he smoke?” she said.

“Sure he does,” I said. “Harriet’s very suicidal.”

“Is he around?” she said.

“He’s around someplace.”

“Would he have a match?” she said.

“Harriet’s out of cigarettes, not matches,” I said. “He smokes Merits. May I take him those?”

Then I did a crazy thing, maybe out of excitement over who she was, maybe out of self-consciousness at who I wasn’t: I began to try and get the pack away from her. She held on to it hard, and we began this tug-of-war, laughing and pushing each other, stumbling around together on the beach until she finally wrenched herself free and ran toward her towel. She scooped it up, along with a beach bag, and headed toward the hardpacked sand near the surf, running fast, but calling over her shoulder, “Good-bye!”

“Wait a minute!”

“I can’t. Good-bye!”

I didn’t follow her. I read somewhere in one of my mother’s movie magazines that a lot of famous female stars sit home alone at night because ordinary guys are afraid to pursue them, afraid to be rejected or just figuring someone like that has a whole life going for her, and certainly doesn’t need some average clown butting in.

That was my feeling as I watched her speed down the beach on her long legs; she was a fast runner, too. I had the feeling she didn’t expect me to follow her, and wouldn’t welcome it.

So I just stood there, going over the little interlude detail by detail in my head, fixing the memory of her so I could tell someone about it: Harriet or my sister—my mother, most of all. My mother’d love it that I met Sabra St. Amour on the beach. She’d tell her hairdresser about it and they’d cluck and twitter over it for a whole wash and set.

Then I looked down and saw the large, gold cuff bracelet in the sand. It must have fallen off during our little wrestling match.

I picked it up and read the inscription inside.