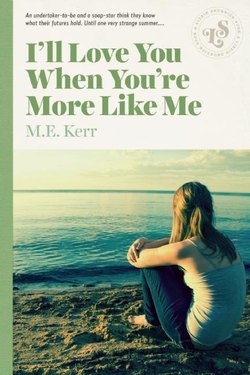

Читать книгу I'll Love You When You're More Like Me - M.E. Kerr - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. Sabra St. Amour

I never like to watch our show on tape, but Mama had gone through all the trouble of getting a television set for our beach house, and hooking it into cable so CBS would come in.

There I was in all my gory glory on a hot August afternoon playing a character who had only one thing in common with me: the name. Mama actually changed our name to St. Amour about a year after I landed the role on Hometown.

Back in The Dark Ages (just after my father was killed in a plane crash) I was fat little Maggie Duggy from Nyack, New York, complete with pimples and an inferiority complex. (It didn’t help matters that Mama remarried eight months later.) Now I’m Sabra and Mama is Madam St. Amour, and we live in the famous Dakota apartment building on Central Park West in New York City.

For the month of August we were vacationing in Seaville, in the Hamptons, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Manhattan. Mama likes to make the trip in my new little white Mercedes, with the top down, a tape of Frank Sinatra singing “My Way” playing, and Mama passing every car on the road, calling out, “Okay, you other mothers, clear the way! We’re coming through!”

Mama enjoys success.

I was watching the ocean through our picture window, wishing I could smoke, pretending I was interested in my performance. Since I wasn’t going to be doing the soap much longer, I wasn’t that fascinated, but I didn’t like to hurt Mama’s feelings. She was sitting in the Eames chair with her feet up, taking notes while she watched, the way she always did.

Mama looks a lot like the actress Shelley Winters. Back in The Dark Ages when my stepfather, Sam, Sam, Superman was alive, he used to tell her she was another Marilyn Monroe. (That didn’t stop him from plucking her out of the limelight into the two-bedroom Cape on a wooded half acre, complete with washer/dryer/dishwasher/self-cleaning oven and automatic garbage disposal.) Mama’s plumper now, very blond with light blue eyes and a whole mouthful of perfectly capped teeth. She has a very kind face, the sort that makes it hard to turn her down, and she’s always surprising me with something. That morning when I walked out onto our deck for breakfast, there was this large, gold cuff bracelet resting on top of my napkin.

“What’s this for?” I asked her.

“It’s for you, sweetheart. Do I have to have a reason to give my own kid a present?”

“It’s beautiful!” I said. “Mama, it must have cost a fortune!”

“Read the inscription inside,” she said.

It was engraved in very tiny letters:

FOR ALL I KNOW YOU’RE ROME

AND PARIS, TOO, I’M HOME

WITH DREAMS AND YOU—THAT’S ALL I NEED;

YOU CUT YOURSELF, I BLEED.

“Oh, Mama!” I said. “That’s sad.”

“The hell it is,” she answered. “That’s motherhood.” She laughed, reached for a pack of More cigarettes, changed her mind because of me and the fact I’m not supposed to smoke anymore.

“You can have one,” I told her. “There’s nothing wrong with your health.”

“I’m going to give them up, too, baby,” she said, “and until I do, I’m not going to smoke in front of you.”

I said, “I wish you would,” but I knew she wouldn’t. For five years, ever since I got my first part in a Broadway show at age thirteen, Mama has lived for me. That isn’t as awful as it sounds, because before she lived for me, she was living for Sam, Sam, Superman, who was lucky if he could afford to take her out once a month for the $2.40 special at Howard Johnson’s.

Near the end of the show, just when the crawl was starting with the credits, there was a shot of me and the poster Mama had bought me once for my dressing-room wall. The producer of Hometown, Fedora Foxe, had seen the poster during a visit to me, and immediately had a writer put it into the show. Fedora was always having things written into the scripts that the cast did or said; she liked to say no fiction in the world could match the drama of real life.

“Accept me as I am,” I was saying on the television screen, “so I may learn what I can become.”

“There should have been a long pause there,” said Mama.

The theme music swelled up and there was a fadeout on my face with this superthoughtful expression.

“Did you hear what I said, honey?” Mama said.

“You said there should have been a long pause there.”

“Do you know what I mean?”

“Sort of.”

“I mean between ‘Accept me as I am,’ and ‘so I may learn what I can become.’ Right after ‘am,’ you should have looked up wistfully, beat, beat, another beat, and then, as though you were getting it all together in your head, into ‘so I may learn what I can become.’ See what I mean, sweetheart?”

“I see.”

“Three beats, and then finish.”

“Okay,” I said, “I see.”

“It was peachy the way it was—don’t get me wrong, but it could have been just a little better.”

I sighed, unintentionally, and Mama looked across at me with this concerned expression. “Why the sigh?”

“Oh Mama, it just seems silly now to worry about it.”

“Who’s worried about it? I said it was peachy.”

“I know you did.”

“I’m just your silly mother, The Perfectionist, don’t pay any attention to me.”

“Mama,” I said, “have you told Fedora what Dr. Baird said?”

“I wrote her a long letter, honey. I don’t want you to worry about anything. From now on we concentrate on getting you better.”

“If that’s possible,” I said. “Sam, Sam, Superman’s ulcers never did get better.”

“You know, sweetheart,” Mama said, “I wish you wouldn’t call your stepfather that.”

“You called him that.”

“But that was different,” Mama said. “I meant it affectionately.”

“You must have felt a lot of affection for him while you were loading up the dishwasher every morning, knowing you could have been in front of a camera instead.”

“It was my own idea to give up my career,” Mama said. “Sam never asked me to give up my career. Your stepfather was a wonderful man, honey.”

“Except he gambled away every cent we ever had,” I said. “May he rest in peace.”

“He didn’t always have good judgment,” said Mama, “but Sam would give you the shirt off his back.”

“To iron for him,” I said.

“Oh, honey, don’t be bitter,” said Mama. “We came out okay. Look at us!” Mama said, waving her hands around the room. “This isn’t exactly chopped liver, baby!”

I saw her starting to reach for her pack of Mores again, then stopping herself. She’d gone half an hour already without a cigarette. I’d gone a week, with a few sneak smokes when I was out of her sight, which wasn’t often. Mama and I did everything together, went everywhere together. When we were separated, we were on the phone together. It was as much my doing as hers—I have to be honest about that. I felt right with Mama close, unsure of myself when she wasn’t around.

Mama said, “Maggie, sweetheart”—she always called me Maggie when she was being her most sincere self—“this is your vacation. Stop worrying. Ulcers heal. There’ll be other roles, better ones. You just toast yourself in the sun, run on the beach and forget your troubles.”

I stood up and turned off the set. I was going to take a walk on the beach so we could both sneak a smoke. “Mama,” I said, “won’t you miss doing the show?”

“You did the show, Tootsie Roll, I didn’t.”

“You know what I mean, though. We’ll be civilians.” It was an old term Fedora still used for anyone who wasn’t in the business.

Mama gave my rear end a swat with a copy of Soap Opera Digest. “Don’t you sneak a cigarette wherever you’re going now,” she said. She knew me like a book.

“The last time I quit smoking, I went up to a hundred and thirty,” I said. “And remember the way I looked in The Dark Ages? Sam, Sam, Superman used to call me The Blimp.”

“He didn’t mean that in a bad way,” Mama said. (I don’t know how anyone could mean it in a good way.) “I’m no sylph myself. Once we’ve both kicked the filthy habit we’ll look like a pair of beached whales for a while.”

We both started laughing then. We laughed for a long time, longer than the joke was funny. I’m not sure what Mama was laughing at, but I think I was laughing because I was relieved. I got my ulcer around the time Fedora began talking about extending Hometown a half hour. When Dr. Baird told Mama he didn’t advise my doubling my work load, I expected Mama to go into a real tailspin. She didn’t, though; she just sat across from him saying, “I couldn’t agree more,” but it never rang true to me somehow. Mama thrives on show business. If she had to choose between going for a day without any food and reading Variety, she’d choose Variety . . . and Mama loves to eat, a lot!

I still remember the time Mama got a sort of crush on the leading man in Hometown. She was spending a lot of time on the set with him, going across to McGlades for drinks with him, talking for long hours on the telephone with him at night. His wife complained to Fedora about it, and Fedora told Mama she was going to end my storyline if Mama didn’t do something about it.

Mama sent me to the set while she sat around The Dakota swallowing Valium and listening to old Tony Bennett tapes for hours on end, smoking and staring at the walls. We couldn’t talk about it together. Mama could never admit that Nick was just this pompous creep who went around trying to make any female in his path fall in love with him. It gave me stomachaches to hear Mama defend Nick, and we went through a bad time when we hardly talked at all.

Then one day after months had gone by, Mama came to the set as though it had all never happened. She gave Nick a smile, that was it, and went back to being my mother, cleaning up my dressing room, fussing over my wardrobe, cueing me and brushing out my long, blond hair—the whole bit. She even called Fedora, who was on the coast at the time.

“Well,” she said, “the news from this end is that the great storm has passed, the sea is calm, the little skiff is not capsized, sails are up. We’re still very much in the race.”

I don’t know what Fedora’s answer was, but I do remember the next thing Mama said.

She said, “Now get her that new storyline you’re always promising, toss in five hundred extra clams a month, and we’ll be back in business.”

It was right after that when Fedora started the whole “Tell me more” bit which made me famous.

The only flaw Mama has is that she’s overprotective. She’d keep me under glass if she could, until she was sure I was able to handle myself to her satisfaction, which would be sometime when I’m forty.

Around the time I got my ulcer, Fedora was trying out this new young writer named Lamont Orr. She wasn’t sure whether she was going to keep him as part of her regular stable of writers or not. The cast called him Lamont Bore, because he couldn’t stand to have one word of his dialogue changed, even when it didn’t play well. Here was this twenty-four-year-old, apple-cheeked kid, who’d never written anything but a few weird off-off-Broadway shows and some daytime television, trying to throw his weight around with talent that had been in the profession for years and years.

Fedora let him hang around the set to get the feeling of the show, and she sent us off for Cokes together to see what kind of a rapport we’d have. When Mama would try to come with us, Fedora would dream up some reason to have a conference with her. Once she just said flatly, “I want them to get to know each other, Peg! They have to, you know, if Lamont does her scenes.”

Mama was always saying things to me like “I guess the kid’s getting to you, hmmmm? He’s okay if you can get past all that Brut he splashes on himself.”

“Mama,” I’d say, “how can a man with a permanent wave get to me?”

“Well it’s the fashion now,” she’d say. “Someday he’ll probably blink his baby blues at you and you’ll be giving him his home permanents yourself.”

We had Lamont to dinner one night, and when he walked through our front door, the first words out of his mouth were, “What a lovely pied-à-terre, Peg!” Peg, he called Mama, when Mama was old enough to be his mother. Pied-à-terre, when he was born and raised in Bolivar, Missouri.

“Oh am I in love!” I said to Mama when he left. “Be still my beating heart! Mama, he compared himself to Dostoevsky. He said, ‘. . . Both Dostoevsky and I believe character development is primary to plot development.’ Did you hear it?”

Mama said, “If he ever . . . if he ever makes even the smallest kind of pass, I want to know about it.”

“Oh the whole world will know about it,” I said. “He’ll cry out, I’ll kick him so hard.”

As I was collecting my bathing suit and towel for a walk to the beach, Mama said to me, “Let me ask you something now. How do you really feel about leaving the show?”

“I think I feel relieved,” I said.

“You think you feel relieved?” she said. “What do you mean you think you feel relieved?”

“I think,” I said, “beat, beat, another beat, I’m relieved.”

“Get outta here!” Mama said. “And good luck with your mouth!”