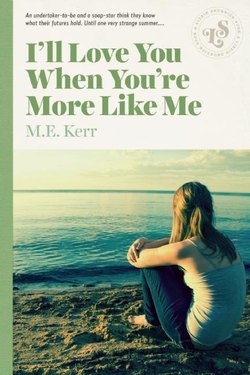

Читать книгу I'll Love You When You're More Like Me - M.E. Kerr - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. Wallace Witherspoon, Jr.

One warm night in May, in the back of the hearse, while I was whispering “I love you, I love you,” into Lauralei Rabinowitz’ soft, black hair, she said, “Stop right there, Wally! There are three reasons this can’t go on any longer!”

“Three reasons?” I said.

“Three reasons,” she said, sitting up, reaching into her blazer pocket for her comb. She combed her hair while she told me what they were.

“One,” she said, “you’re not Jewish.”

“Two,” she said, “you’re shorter than I am.”

“And three,” she said, “you’re going to be an undertaker.”

“You knew all that!” I complained.

“I know I knew all that,” she said, “but I couldn’t stop myself before. Now I’m stopping myself.”

“You can’t!” I insisted. “I’ll probably want to marry you someday.”

“I just did,” said Lauralei Rabinowitz, “and I’d never marry you in a million years, Wally Witherspoon.”

So much for ancient history. I am now unofficially engaged to Harriet Hren, who does want to marry me, isn’t Jewish, and standing, even in heels, just reaches my shoulder.

Our plans to marry when we both graduate from Seaville High next year were made on another warm night, in June, in the back of the same hearse.

“How do I know you’re really over Lauralei?” Harriet had asked me in the middle of things.

“What would I be doing here if I wasn’t over Lauralei Rabinowitz?” I answered.

“You would be trying to make out here,” said Harriet.

“What kind of a person do you think I am?” I said.

“I’ll know when you answer this question: Are you going to marry me?”

“I’m not going to marry Lauralei Rabinowitz,” I said.

“Are you going to marry me?”

“When?”

“A year from now,” said Harriet.

“Yes,” I said, “a year from now, yes.”

“Are you going to ask my mother if you can?”

“I thought it was the father you asked if you could.”

“My father’s in Akron,” said Harriet. “He won’t be home for another week. I want you to ask my mother if you can tonight.”

“All right, I’ll ask your mother tonight,” I said. “Tonight?”

“Tonight,” Harriet said, “because she thinks you’re just using me to get over Lauralei Rabinowitz.”

Both Harriet’s parents were C.P.A.s, and when you spoke to either of them there was usually an adding machine going. Everyone in Seaville used the Hrens as their accountants. The only thing they seemed to do besides add up figures was add to the population. Harriet had five brothers and two sisters.

“Fine,” Mrs. Hren said when I announced my intentions, a cigarette dangling from her mouth, smoke curling up past her face, “but Harriet has to”—clickety clack the adding machine went—“finish high school, you realize”—clickety clack—“that, don’t you, Wallace?”

Which was how I became unofficially engaged.

Engagements, according to Harriet, are not official until the girl gets the ring.

Our subject of conversation for the rest of the summer was The Ring.

One hot afternoon in August, we were once again discussing The Ring. Harriet was stretched out on the wicker couch, in the Hrens’ one-room beach house at the ocean. She was all in white. When anyone is stretched out all in white in my house, it means they’ve “crossed over,” as my mother likes to put it. I am the sixteen-year-old, only son of the leading Seaville mortician. My father prefers the description Funeral Director.

“Ideally, I would like to have the ring by the time school starts,” Harriet was saying.

“Ideally, I would like to inherit a million dollars by the time school starts,” I said.

“How much do you have saved so far?” Harriet said.

“I have thirty dollars so far,” I said. “Engagement rings are supposed to be passé.”

“My mother had one and my mother wants me to have one,” Harriet said.

“Why doesn’t your mother buy you one then?” I said. “Your mother probably has more than thirty dollars saved.”

“I can lend you a hundred dollars,” Harriet said. “We’ll talk about it during the commercial.” We were both watching a soap called Hometown. All the kids were watching it that year. The reception was fuzzy because the Hrens had an old black-and-white set in the beach house which was hooked up to a battered antenna atop the roof. Every time a strong gust of wind blew in from the ocean, the actors shook and faded.

I was lying on the rope carpet with my feet up on an old streamer trunk the Hrens used as a coffee table. I was studying Harriet, trying to see her through the eyes of Lauralei Rabinowitz, who kept returning to my mind like mildew you can’t get off a suitcase no matter how often you set it out in the sun and purge yourself of it. Maybe she was more a disease than simple mildew, a disease so far unrecorded in the annals of medical history. Years hence I would be told, “It’s Rabinowitzitis, all right, you’ve been suffering from it since before your marriage. You have all the symptoms. I’m surprised you didn’t notice a certain apathy alternating with periods of deep depression.”

Harriet was prettier than Lauralei—Lauralei would have to give her that. She was petite and Lauralei was built like a phys-ed teacher; she was blond and hairless and Lauralei shaved every other day. She was blue-eyed and pug-nosed and Lauralei was brown-eyed and longing for a nose job. . . . But Harriet was a math lesson, and Lauralei was a whole course in chemistry, and it was Lauralei I wished I was trying to get out of buying a ring for.

“Harriet,” said my mother, “is a nice girl and she’ll be an asset in the business.”

“That girl,” said my mother some time back about Lauralei, “will never settle for Seaville. You think she’ll come back to you after she goes to Ohio State?”

“Why do I have to think about those things now?” I used to say.

“Because now is when you’re going to get in trouble if you don’t get control over yourself. Stay out of the hearse, too, or I’ll tell your father you’ve been in there with her.”

Lauralei Rabinowitz did not come into my life until the middle of my junior year, when her family moved from New York City to Seaville. Before she first bumped up against me in the hall, laughing at me with her dark, sexy eyes and letting me have my first whiff of Arpege, the French perfume she touched to her ears every morning before she left the house, I was a simple son of an undertaker, the brunt of many jokes and used to it, a bookworm for compensation. My only accomplishment B.R. (Before Rabinowitz) was to win an essay contest in Mr. Sponzini’s English class.

My composition was called “Evasions” and it was inspired by my mother’s habit of refusing to say that anyone died. Someone “crossed over,” “went to her reward,” “passed on,” “drew his final breath,” on and on. I spent hours in the library elaborating on my theme, working myself into a sweat over the discovery that the Malays have no name for tiger, lest the sound of it might summon one; that in Madagascar the word “lightning” is never mentioned for fear it might strike; that Russian peasants have no name for their enemy, the bear (they call him “honey eater”); and that in Hungary the mothers of new babies were once told “What an ugly child,” to placate evil spirits and make them less jealous.

“Brilliant work, Wally!” Mr. Sponzini wrote across the top of my essay, but it did nothing to stop Duffo Buttman from following me home singing to the tune of “Home on the Range” “Oh give me a home, where the corpses all roam, and the ghosts in the caskets do play . . .” and it did nothing to prevent Miles Wills from calling across a classroom, “What are you going to undertake today, Witherspoon?”

Before Rabinowitz, I consoled myself with the idea that one day every one of them would be wheeled Mr. Trumble’s way. He was my father’s assistant, in charge of receiving. But that was not a lot of consolation, considering the fact that Mr. Trumble was in his late sixties, and I was in line for Mr. Trumble’s job, and even if Duffo Buttman himself were to arrive stiff and white and ready for the grave, I would rather die myelf than be a party to the necessary embalming.

“You’ll get over it,” my father would tell me.

“Oh no I won’t,” I’d say emphatically, “ever!”

“Wallace!” my mother said then, raised eyebrow, eyes narrowing to caution me not to get my father excited, his heart was weak.

Then Lauralei Rabinowitz came and did battle with my badly battered ego, suggesting the back of the hearse herself one night, and we fell in love the way a storm rages, or a rock number builds, the way you fly in dreams all by yourself, or go down a roller coaster smiling while you’re screaming, with the wind trying to push you back and the earth turning before your eyes.

“Where is love?” I argued with her our last night in the hearse. “Where is love in all this talk of height and religion and profession?”

“Listen, Wally,” she said, “Maury Posner’s coming by my house in an hour to borrow my notes from Earth Science, so I can’t continue this discussion.” She was still combing her hair.

“Maury Posner’s shorter than I am!” I yelled.

“He’s Jewish, though,” she said, “and he’s already got a bid for the Zebe House at Ohio State.”

“It’s over,” Harriet said. For a second I thought she was reading my mind (only my mind always shouted it: RABINOWITZ IS OVER!), but she was talking about the soap. It was all over except for a last tease, a brief look at the next day’s episode.

On the screen was Sabra St. Amour. She played a teenager on the soap, this tall, green-eyed girl with very light blond hair spilling down to her waist. The same way The Fonz was always saying “H-eee-EEY” on Happy Days or J.J. said “Dy-no-mite!” on Good Times, Sabra St. Amour’s trademark was “Tell me more.” She’d milk those three words for all they were worth, and around school you’d hear kids saying “Tell me more” the same way she said it. There were “Tell me more” T-shirts with her face on them. There was a song called “Tell Me More,” recorded by The Heavy Number. She’d done a T.V. special last winter called “Tell Me More,” which was a series of really bad comedy skits, but it didn’t matter because all she had to say was “Tell me more,” and everybody would fall apart.

During the tease, Sabra St. Amour was hanging up a poster in her bedroom. She’d just moved to another town to start over, after her movie-star mother had shot another woman’s husband in their love nest. The poster was an ocean scene, not unlike the one Harriet and I could see from the Hrens’ beach-house window. There was surf washing up on the beach. Sabra was reading something printed on the poster while the crawl of credits was passing across her face.

“Accept me as I am,” said Sabra in a slow, wistful voice, “so I may learn what I can become.”

Then the music began to swell, and the theme of Hometown sounded on the organ, while the camera did a slow fade-out.

“I can lend you a hundred dollars toward the ring,” Harriet said, punching the Off button on the remote control.

“Nobody else in the senior class is going to have a ring, Harriet,” I said.

“My mother had hers by her senior year,” she said. “She had a half-a-carat Keepsake.”

“Why don’t we take a walk on the beach?” I said.

“You wouldn’t have to pay back the hundred till after we were married.”

“It’s a beautiful day,” I said.

“I don’t want to miss Star Trek,” Harriet said. “Mr. Spock is going to desert the Enterprise for a strange, female creature from an alien colony.”

“Do you mind if I take a walk?” I said.

“Alone?” Harriet said.

“Alone,” I said, but it didn’t turn out that way, even though Harriet stayed behind.