Читать книгу In the Heat of the Summer - Michael W. Flamm - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

THE GREAT MECCA

Drunk with the memory of the ghetto

Drunk with the lure of the looting

And the memory of the uniforms shoving with their sticks

Asking, “Are you looking for trouble?”

—Phil Ochs, “In the Heat of the Summer”

1873–1963

In the summer of 1933, Bayard Rustin made his first visit to Harlem. A tall and handsome young man with a restless mind, athletic build, and musical talent, he was born in Pennsylvania in 1912, the son of unmarried parents he never really knew. He was raised mostly by his grandmother, who was educated in integrated Quaker schools and influenced by Quaker ideas. But she could not shelter him from the realities of the world. One of Rustin’s earliest brushes with discrimination came when, as a member of the West Chester High School football team, he was denied service in a restaurant in the nearby town of Media and decided to stage his own sit-in, three decades before the famous Nashville protests of 1960. “I sat there quite a long time,” he noted later, “and was eventually thrown out bodily. From that point on, I had the conviction that I would not accept segregation.”1

After his first year at Wilberforce University in western Ohio, Rustin came to New York to see his aunt, a teacher who lived in Harlem. By then the Great Depression was in full force—only months earlier newly elected Franklin Roosevelt had taken the oath of office and assured the nation that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” But pure excitement was the twenty-one-year-old Rustin’s initial reaction when he arrived in Harlem. “A totally thrilling experience,” he recalled. “I’ll never forget my first walk on 125th Street.… I had such a feeling of exhilaration.”2

New arrivals often had a similar response because 125th Street was the main artery of Central Harlem, the historic and symbolic heart of black America. Stretching roughly from 110th Street (the northern border of Central Park) to 145th Street, Fifth Avenue to Morningside Park and St. Nicholas Park, the neighborhood was overwhelmingly African American. By contrast, East Harlem and Spanish Harlem were more mixed, with large numbers of Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, and Puerto Ricans.

“Harlem is indeed the great Mecca for the sight-seer, the pleasure-seeker, the curious, the adventurous, the enterprising, the ambitious, and the talented of the whole Negro world,” James Weldon Johnson, the noted author, poet, lawyer, diplomat, and first black executive secretary of the NAACP, wrote in the 1920s. “It is a city within a city, the greatest Negro city in the world.” But the energy of Harlem could not disguise the fact that it was also a ghetto, with all of the underlying social and economic problems that typically added fuel to the fires of outrage. Periodically, the community exploded, most notably in 1935 during the Great Depression and in 1943 during World War II, even as the same conditions persisted into the 1950s and 1960s. To appreciate what happened in 1964 it is important to understand the history of Harlem.3

After the Civil War, New York City underwent an urban revolution. New neighborhoods were needed as the population surpassed a million, and in 1873 Harlem was annexed. By 1881 the elevated railroad had reached 129th Street and a building boom soon followed, with row upon row of elegant brownstones and exclusive apartments constructed on broad and leafy streets in the next two decades. It was, predicted a magazine in 1893, inevitable that “the center of fashion, wealth, culture and intelligence must, in the near future, be found in the ancient and honorable village of Harlem.”4

The real estate speculators assumed that if they built it, wealthy whites would come to Harlem in search of fresh air and living space as well as an escape from the noise and congestion of the city. But not if they had to share the area with blacks, who were not welcome. So commercial banks were pressured not to offer mortgages to African Americans. Property owners were forced to sign restrictive covenants stating that they would rent or sell only to Caucasians. And neighborhood associations were formed to defend the color barrier. “We are approaching a crisis,” declared the founder of the Harlem Property Owners Improvement Corporation in 1913. “It is the question of whether the white man will rule Harlem or the Negro.”5

But by then it was too late. A wave of speculation in Harlem had swamped the housing market, causing it to collapse in 1905 amid a sea of unsold and unrented buildings. Meanwhile, black migrants from the South and immigrants from the Caribbean were flooding into other parts of the city, causing apartment shortages and rising rents. Tensions also festered between longtime residents and new arrivals, both the native- and foreign-born, which caused lasting divisions within the black community. At the same time, urban renewal and commercial expansion, such as the construction of the original and ornate Pennsylvania Station, were destroying affordable housing and dislocating black residents in Hell’s Kitchen on the West Side and in Midtown Manhattan.

Into the breach stepped entrepreneurs such as Philip Payton, founder of the Afro-Am Realty Company, which began to lease Harlem properties from white owners and then rent them to black tenants. Payton was a graduate of Livingston College in North Carolina who had moved to New York in 1899 to make his fortune. After working as a handyman, a barber (his father’s trade), and a janitor in a real estate office, he saw his chance and seized it. Another opportunist was Solomon Riley, a barrel-chested Barbados native with a Caucasian wife who followed the same strategy as Payton. “I decided to turn the sword’s edge the other way” was how he put it.6

The Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) line along Lenox Avenue, completed in 1904, opened the floodgates to black families eager to enjoy the good life and spacious apartments in Harlem. Their ranks grew as the economic stimulus of World War I created job opportunities in northern factories and reinforced the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South. In the decade after 1918, almost a hundred thousand blacks moved to Central Harlem, which by 1930 was home to almost two hundred thousand African Americans, more than 65 percent of New York’s black population and 12 percent of the city population.7

By the Jazz Age Central Harlem had become the place where African Americans could enjoy the “fundamental rights of American citizenship” according to Johnson, whose mother hailed from the Bahamas. “In return, the Negro loves New York and is proud of it, and contributes in his way to its greatness.” During the 1920s and 1930s, greatness was everywhere as the Harlem Renaissance attracted the most gifted and talented blacks from across the United States and the West Indies.8

Entertainers like Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Florence Mills, Bert Williams, Bessie Smith, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and Fats Waller graced the stages of the Apollo Theater, the Cotton Club, Small’s Paradise, and the Savoy Ballroom. Writers and poets like Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston dazzled the literary world. And scholars like E. Franklin Frazier, a Howard University sociologist, and Alain Locke, the first African American Rhodes Scholar and author of The New Negro, produced important studies of black society.9

At the same time, institutions both sacred (such as the Abyssinian Baptist Church, which soon had the largest Protestant congregation in the country) and secular (such as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) enriched life in Harlem. It was also the center of African American political thought and hosted The Crisis, a magazine published by the NAACP and edited by W. E. B. Du Bois and Jessie Faucet; Opportunity, a journal published by the National Urban League and edited by Charles S. Johnson; and the Messenger, a monthly originally sponsored by the Socialist Party and edited by A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen.

But the glamour and sophistication of the Harlem Renaissance could not hide the fact that the community was not monolithic. On the contrary, it was diverse, with deep divisions between the “respectable” churchgoers and the “rebellious” street people, the middle class and the lower class, the native-born and the foreign-born, the light-skinned and the dark-skinned. In the 1920s, most blacks also could not escape the strains of everyday life in Harlem, where it was a constant struggle to make ends meet amid low incomes and high rents (whites continued to own the vast majority of properties and businesses). With crowding and congestion at extreme levels, death by violence and disease was rampant. Mothers in Harlem died in childbirth at twice the rate of mothers in other parts of the city; the infant mortality rate for blacks was almost twice as high as for whites. Rickets, a bone disorder caused by malnutrition, was common.10

No wonder that when the Great Depression arrived it “didn’t have the impact on the Negroes that it had on whites,” observed George S. Schuyler, a novelist, journalist, and skeptic of the Harlem Renaissance, because “Negroes had been in the Depression all the time.” He was essentially right, but by the early 1930s a bad situation had grown even worse. Across New York the homicide rate fell—but not in Central Harlem, where it rose significantly. Malnutrition among children was three times the rate of the rest of the city. And disease remained at epidemic levels—the rate of tuberculosis among blacks was four times the rate among whites, although mortality rates on the whole declined due to better health care and free medical clinics.11

Led by Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, a liberal Republican with strong ties to the black community, New York offered relatively generous relief assistance. Federal aid also came from the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a liberal Democrat and former governor of New York who actively sought black votes. But although African Americans in Central Harlem enjoyed real benefits that prevented mass hunger and deprivation, in general they received less than their fair share of public welfare, often as a result of racism and discrimination. In response, private institutions like Abyssinian Baptist, headed by the influential minister Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. and his son Adam, the assistant pastor, tried to meet the growing need with soup kitchens, clothing drives, and homeless shelters.

Under the dynamic leadership of Powell Sr., who was named pastor in 1908, Abyssinian Baptist had a congregation of ten thousand and was the most prominent church in Harlem. Powell Jr. was an only son, the adored and pampered child of mixed-race parents. With straight hair and fair skin, he could pass as white, which he briefly chose to do while a student at Colgate University. After college he returned to Harlem in 1930, earned a master’s degree in religious education from Columbia University, and entered the ministry at his father’s side. Handsome and charismatic, he became a popular civil rights leader during the Great Depression, and in 1938 succeeded his father as pastor. Three years later, he was the first black elected to the city council; in 1944, he joined Congress as the first black representative from New York State.12

The root of the problem, Powell Jr. believed, was a lack of jobs. Last hired and first fired, blacks suffered from an unemployment rate at least several times that of whites. In Central Harlem, whites owned three-quarters of the businesses including Blumstein’s, the largest department store on 125th Street. And only one-quarter of those businesses would hire blacks, even for entry-level positions. Frustrated, a broad and uneasy coalition of moderate, radical, religious, and nationalist organizations launched a “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign, which persuaded Blumstein’s to agree to hire fifteen black female clerks, all of them light-skinned and attractive.13

But the department store reneged on promises to hire more black employees, other businesses followed suit, and in 1935 the campaign collapsed amid charges of corruption and anti-Semitism (a majority of white store owners in Harlem were Jewish). “I remember meeting no Negro in the years of my growing up, in my family or out of it,” recalled James Baldwin, the celebrated writer and Harlem native, “who would really ever trust a Jew and few who did not, indeed, exhibit for them the blackest contempt.”14 In the bitter climate of dashed expectations and mutual distrust, the stage was set for an explosion whose causes and aftermath were similar to the 1964 riot.

On the cool afternoon of March 19, 1935, Lino Rivera walked into the Kress Five and Ten store on West 125th Street across from the Apollo Theater. Unemployed and broke, the sixteen-year-old Puerto Rican had spent the day looking for work in Brooklyn and catching a movie. As he strolled through the store around 3 P.M., he noticed a ten-cent penknife on a counter. “I wanted it and so I took it,” he later admitted. Two employees (both white) saw him and grabbed him, but Rivera bit one of them in the hand, drawing blood. They managed to restrain him and summon a police officer, who took the youth to the basement for questioning.15

As a group of onlookers formed, a black woman screamed that they were going to beat or kill Rivera. After she was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct, the arrival of an ambulance—to treat the employee—added to the rumors flying through the crowd. Then the driver of a hearse stopped at the scene and another woman shouted, “There’s the hearse come to take the boy’s body out of the store.” In fact, Rivera was already on his way home—uninjured, he had left Kress through a rear exit after the manager had chosen not to file charges against him. The manager also tried to inform the bystanders, but many had dispersed and so word of the supposed brutality spread like wildfire throughout Central Harlem.16

With counters overturned and merchandise scattered in the aisles, the police began to clear the Kress store and ordered it closed at 5:30 P.M. But as people returned from work and heard the rumors, a fresh crowd gathered. Between 6 and 7 P.M. two groups of young communists, black and white, arrived with newly painted placards and printed pamphlets alleging that Rivera was near death and that the police had broken the arms of the woman who was arrested (neither charge was true). The radicals also organized a picket line and made inflammatory speeches at street meetings. Suddenly, bottles or rocks shattered the large plate glass windows and hundreds of looters swarmed into the five-and-dime, grabbing whatever items they could reach. Thousands of others quickly joined the fray, smashing windows and robbing stores along 125th Street from Fifth to Eighth Avenue.17 The Harlem Riot of 1935 had begun.

The rioters were not solely the “riffraff” or hoodlums as many blacks and whites later claimed—they were a mix of the poor, the provoked, and the prominent. “One of the most unusual was a Harlem playgirl and relative of one of the most conservative of Harlem’s ministers,” wrote Claude McKay, the gifted author and poet from Jamaica. “Under her coat she was carrying a bag full of bricks and was taxied from place to place hurling them through the plate glass.”18

Sixteen years earlier, during the race riots that marked the “Red Summer” of 1919, McKay had composed “If We Must Die,” an anthem for the “New Negro” movement. “Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,” the poem declared, “pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” Now McKay belittled the 1935 riot as little more than a “party.” Few whites were affected, he observed, and then “not nearly to the extent they might be during the celebration of a Joe Louis victory.”19 But as always, blacks who lived and worked in Harlem would pay for the party and suffer the hangover.

After a desperate search, the police located Rivera and brought him back to the Kress store at 2 A.M. to demonstrate that he was unharmed. But they failed to make effective use of radio stations or sound trucks and by then the looting had spread south to 120th Street and north to 138th Street as owners rushed to post signs indicating that the business employed African Americans or was black-owned. In his classic novel Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison described the scene: “The crowd was working in and out of the stores like ants around spilled sugar…. I saw a little hard man come out of the crowd carrying several boxes. He wore three hats upon his head, and several pairs of suspenders flopped about his shoulders, and now as he came toward us I saw that he wore a pair of gleaming new rubber hip boots. His pockets bulged and over his shoulder he carried a cloth sack that swung heavily behind him.”20

More than five hundred officers raced to Harlem and flooded the area. In the streets, squads of mounted and foot patrolmen waded into the crowds, which had grown to around three thousand, using their night sticks and gun butts on rioters. On the rooftops, police combed tenement buildings in an effort to arrest snipers and halt the fusillade of “Irish confetti” (bricks, bottles, and bats) that rained down on their fellow officers below. Emergency units and prisoner wagons occupied strategic positions throughout Central Harlem while radio cars cruised the blocks and tried to coordinate operations. The next morning order was restored, but not before one male was dead (two more would die later) and more than a hundred (including seven officers) were wounded. Another 125 were arrested (mostly black youths charged with disorderly conduct or inciting to riot), and more than two hundred stores were vandalized if not looted.21

The overwhelming majority of police were white, which aggravated the confrontation. Before the riot began, several black residents politely asked officers in the Kress store about the condition of Rivera. It was, they were gruffly informed, “none of their business.” An older woman made another plea: “Can’t you tell us what happened?” She was warned to move on “if you know what’s good for you.” Once the looting was under way, witnesses asserted that one of the victims, a high school student coming home from a movie with his brother, was shot and mortally wounded by a white policeman who never fired a warning shot or told the black youth to halt when he ran from the officer as part of a crowd outside an auto supply store.22 More black police, testified the ranking African American officer in the NYPD at the first public hearing of the mayor’s commission to investigate the riot, could have made a difference because they were better suited to handle trouble in Harlem.23

In the debate over who caused the explosion, Mayor La Guardia and city officials immediately cast blame on the communists, who in their view had sought to exploit the racial unrest for political gain. “We have evidence,” charged Manhattan District Attorney William Dodge, “that two hours after the boy stole that knife the Reds had placed inflammatory leaflets on the streets.” He announced that he would convene a grand jury “to let the Communists know that they cannot come into this country and upset our laws.”24

Black conservatives were careful to finger white radicals and agitators. “The peace of Harlem was disrupted by people from other places last night,” stated Fred R. Moore, editor of the New York Age (an African American newspaper) and a former alderman. “These people were dissatisfied with the place they came from and they are dissatisfied with American ways. They were determined to incite irresponsible people to revolt against law and order.… We are a peace-loving people who never subscribe to so-called ‘red’ notions.” An elderly waiter called white communists the “prime instigators,” and a window washer concurred.25

Black radicals in turn initially pointed to the white police, whose “brutality and provocation against the Negro people” had triggered the “race riots” according to James Ford, executive secretary of the Harlem section of the Communist Party.26 But most African Americans—including the communists in time—placed primary responsibility on the economic pressures in Central Harlem.

“Continued exploitation of the Negro is at the bottom of all the trouble, exploitation as regards wages, jobs, and working conditions,” contended the younger Powell. A porter stated that the “rioting was due to economics” and a barber agreed. “The Communists are only responsible for setting off the fuse; the situation already existed,” he told a reporter for the Amsterdam News. In “Declaration of 1776,” educator Nannie Burroughs outlined a broad and deep history of oppression and discrimination. “The causes of the Harlem Riot are not far to seek,” she asserted. “Day after day, year after year, decade after decade, black people have been robbed of their inalienable rights…. That ‘long train of abuses’ is a magazine of powder. An unknown boy was simply the match.”27

After the initial hysteria had subsided, La Guardia had second thoughts about the communist plot, alleged or otherwise, and convened a commission with E. Franklin Frazier as researcher to explore the underlying causes of the Harlem Riot of 1935. Chaired by Dr. Charles H. Roberts, a black dentist and city alderman, the commission held twenty-five hearings and interviewed 160 witnesses; ultimately, it concluded—as would the FBI report after the 1964 riot—that the “outburst was spontaneous and unpremeditated” with “no evidence of any program or leadership of the rioters.” At first looters targeted white stores, but soon “property itself became the object of their fury.”28

The report was highly critical of the NYPD in general and how it reacted on March 19 in particular. “The police practice aggressions and brutalities upon the Harlem citizens not only because they are Negroes but because they are poor and therefore defenseless,” the commission stated. “But these attacks upon the security of the homes and the persons of the citizens are doing more than anything else to create a disrespect for authority and to bring about mass resistance to the injustices suffered by the community.”29

The bulk of the 135-page report, however, focused on the social and economic ills of Harlem. Like the War on Poverty and Great Society programs of the 1960s, it touched on the pressing need for vastly improved public health, education, and housing. The report focused on widespread discrimination in employment and relief, public and private, at both the city and federal levels. And it offered a sweeping set of recommendations—so sweeping, in fact, that when finished a year later, La Guardia opted not to release the report, perhaps because it highlighted problems he could not solve and raised expectations he could not meet. Or perhaps the findings simply were, in the words of the Amsterdam News, which published the full document in July 1936, “too hot, too caustic, too critical, too unfavorable” to his administration.30

The report nevertheless inspired La Guardia to take a more direct interest in the community. “He was not prepared to place Harlem at the center of his agenda,” wrote his biographer, “but he did place it far higher on his list of priorities.” That summer, on his way to a concert, he heard the police broadcast news about a murder in the area and raced uptown to assume personal control and defuse the tense situation. And over the next four years he acted upon many, though by no means all, of the commission’s recommendations. He appointed the city’s first black magistrate, named African Americans to many other municipal posts, integrated the staffs of the city hospitals, built two new public schools, constructed the Harlem River Houses, and added a Women’s Pavilion to Harlem Hospital. For La Guardia, who would serve as mayor from 1934 to 1945, it was a start, albeit overdue and incomplete.31

Two years after the Harlem Riot of 1935, Bayard Rustin moved to New York, where he first lived with his aunt and then found an apartment of his own on St. Nicholas Avenue. The exact reason for his departure from Pennsylvania remains murky. It is possible that he had little choice: Rustin by then had accepted that he was gay and had begun to act upon his sexual desires. The West Chester police may even have caught him having sex in a public park with a prominent young white man and made it clear to him that he had no future in the small town. But it is also likely that he was attracted by the political and cultural opportunities presented by Harlem—not to mention the personal anonymity and social freedom it offered.32

Once Rustin arrived in the fall of 1937, he quickly embraced New York, where he would spend the rest of his life. With his polished tenor voice, he became a member of the Carolinians, a singing group that performed regularly at the Café Society Downtown, a popular club in Greenwich Village. He also joined the Young Communist League (YCL), which was dedicated to the struggle for racial equality and the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine black Alabama teenagers falsely accused of rape. In 1941, after Nazi Germany invaded Soviet Russia and Moscow insisted that the struggle against racism take a back seat to the fight against fascism, Rustin left the YCL. But he was not bitter because his experience as a Communist had given him—a man who never earned a college degree—a crash course in planning and organizing. “It taught me a great deal,” he readily admitted later, “and I presume that if I had to do it over again, I’d do the same thing.”33

Even when Rustin was an active Communist, he continued to sing in church choirs and attend Quaker meetings. So it was not surprising that in 1941, with war on the horizon, he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a Christian pacifist organization led by the socialist A. J. Muste. Like Rustin, Muste was a former Communist, and for a time he served as a sort of father figure to his gifted protégé. He also enabled Rustin to join the crusade of the man who would become his great mentor and patron: A. Philip Randolph, the head of the most important black union in the country, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and the inspiration behind the 1941 March on Washington protest and movement.

As the United States mobilized for war under President Roosevelt, who had won an unprecedented third term in 1940, an economic boom began and the Great Depression at last came to end. Hopes rose in New York, where the black population had grown by another 150,000 since 1930. But prices and rents in Harlem remained high, while discrimination and segregation in training programs and war plants remained common—90 percent refused to hire African Americans, who represented less than half a percent of the workforce.34 In 1941, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which had the strong support of La Guardia and banned racial discrimination in defense industries. The action came in response to Randolph’s threat of a mass demonstration in Washington, and it led to the creation of the Fair Employment Practices Commission, which had some effect. Eventually, African Americans received real benefits from war mobilization as jobs arrived and paychecks grew. But as with the New Deal, blacks again failed to receive their fair share of government programs and contracts.

Frustration and resentment mounted. In 1941, at the age of thirty-three, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. was elected to the city council and became a harsh critic of La Guardia, who had failed to implement many of the recommendations in the 1935 report. “The Mayor is one of the most pathetic figures on the current American scene,” Powell wrote in 1942. “Now that his political future is finished, we are no longer potential votes for him. We are therefore ignored.”35

A year later, a race riot erupted in Detroit, where tensions between southern whites and blacks who had migrated north in search of jobs had reached a crisis level. On June 20, a hot Saturday evening, crowds clashed in Belle Isle as rumors swept the city that blacks had raped and murdered a white woman while whites had murdered a black woman and her child, then dumped the bodies in the Detroit River. Over the next three days, thirty-four people were killed, twenty-five of whom were black (seventeen were shot by white officers). Hundreds were injured. Only the arrival of the U.S. Army, ordered to Detroit by President Roosevelt, restored a fragile and bitter peace. The nation watched in shock and horror.

In New York, the fear was that Harlem was next. On June 24, Powell demanded that La Guardia meet with him and said at a city council meeting that if a riot erupted in New York “the blood of innocent people … would rest upon the hands” of the mayor and police commissioner.36 La Guardia refused, perhaps understandably, to meet with Powell, but conferred with other black leaders. In July he made plans in case of violence to close bars, divert traffic, place guards at stores that sold weapons, and protect passengers using public transit. The mayor also had the police commissioner emphasize that officers should demonstrate restraint by using tear gas and deadly force only as a last resort against physical harm.37

At the same time, La Guardia prodded the NYPD to promise to hire more blacks—of the roughly 19,000 officers on the force, only 140 were African American, with 130 stationed in Central Harlem or Bedford-Stuyvesant. Another twenty cadets (the largest group to date) were in the Police Academy. Among them was Robert Mangum, who in 1943 helped found the Guardians, an association of black officers, because the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) refused to accept them. At first the Guardians had to meet secretly at the Harlem YMCA because of opposition from supervisors. Not until 1949—with the support of Powell, who in 1944 had joined the U.S. House of Representatives—would the Guardians receive a charter of recognition from the city.38 It would take far longer for them to gain respect from their fellow white officers.

La Guardia’s efforts in the summer of 1943 were in vain, although they may have limited the bloodshed to come. On August 1, a hot Sunday evening, everyone in Harlem was outdoors, trying to beat the heat in the absence of air conditioning. At 7 P.M. Marjorie Polite registered at the Hotel Braddock on West 126th Street, which was under surveillance for prostitution. Unhappy with her room, she demanded a refund and then got into an argument with the elevator operator, who refused to return a dollar tip that she had allegedly given him. Patrolman James Collins, who was on duty inside the hotel, first tried to calm Polite and then ordered her to leave. When she refused and began to curse at him, he arrested her for disorderly conduct.39

In the hotel lobby was a Connecticut woman, Florine Roberts, who was meeting her son Robert Bandy, an Army private on leave from the 703rd Military Police Battalion in Jersey City. Together, they demanded that Collins release Polite. He refused. What happened next was a matter of dispute. According to Collins, he was attacked for no reason by Roberts and Bandy, who seized his nightstick and began to strike the officer in the head, forcing Collins to use his revolver when the soldier fled and refused to halt. According to Bandy, he objected and intervened only when Collins shoved Polite; the officer then threw his nightstick at Bandy, who caught it and was shot in the shoulder when he was slow to return it.40

Fortunately, the injuries of both men were not serious. Unfortunately, word quickly spread that a white officer had killed a black soldier attempting to protect his mother. The police tried to correct the false rumors, but by 8 P.M. a crowd estimated at three thousand was gathered outside the 28th Precinct, threatening to take revenge against the officer responsible for the alleged atrocity. At 9 P.M. La Guardia rushed to the station house, which was already surrounded by army infantry and military police, and conferred with the police and fire commissioners. With almost manic energy, La Guardia began to give orders and speak to the crowd, urging people to go home. He also took a tour of the riot area, accompanied by local black leaders. Meanwhile, efforts were made to recruit volunteers from the community and bring in reinforcements by keeping all patrolmen on duty when their shifts ended at midnight. Soon Central Harlem was flooded with five thousand police officers and contingency plans went into effect.41

But it was to no avail. At 10:30 P.M. the sound of breaking glass rang through the streets. Claude Brown, author of the memoir Manchild in the Promised Land, was six at the time and thought Harlem was under attack from German or Japanese bombers. He asked his father, a sharecropper from South Carolina, where the sirens were. “This ain’t no air raid—just a whole lotta niggers gone fool,” he replied. But the noise kept Brown scared and awake in his bed for hours.42

Soon looters were rampaging the streets from 110th to 145th, Lenox to Eighth Avenue, filling the air with screams and laughter, although there was a deep undercurrent of anger. “Do not attempt to fuck with me,” a young man told the Amsterdam News. Author Ralph Ellison again found himself in the middle of a riot when he exited the 137th Street subway station after dinner with friends. In the New York Post, he wrote that he sensed shame in some looters like “the woman with her arms loaded who passed me muttering ‘Forgive me, Jesus. Have mercy, Lord.’” Still others seemed filled with self-disgust when “faced with an embarrassment of riches and took only useless objects.”43

By Monday morning Harlem was calm even if 125th Street, the epicenter of the riot, was littered with shattered windows and scattered debris from ransacked businesses. “It would have been better to have left the plate glass as it had been and the goods lying in the stores,” commented novelist James Baldwin, who was in New York to attend the funeral of his estranged father and celebrate his nineteenth birthday. “It would have been better, but it also would have been intolerable, for Harlem had needed something to smash. To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need. Most of the time it is the members of the ghetto who smash each other, and themselves. But as long as the ghetto walls are standing there will always come a moment when these outlets do not work.” For his part, Ellison saw the riot as “the poorer element’s way of blowing off steam.”44

At 9:50 A.M. La Guardia, exhausted, went on the air for the third time. “Shame has come to our city and sorrow to the large number of our fellow citizens, decent, law-abiding citizens, who live in the Harlem section,” he said. “The situation is under control. I want to make it clear that this was not a race riot, for the thoughtless hoodlums had no one to fight with and gave vent to their activity by breaking windows [and] looting many of these stores belonging to the people who live in Harlem.” He also had praise for the police, who were “most efficient and exercised a great deal of restraint.” And he informed the people of Harlem that he expected “full and complete cooperation” while pledging that he would maintain law and order in the city.45

To ensure he would keep his promise, La Guardia had fifteen hundred volunteers, most of whom were African Americans, and six thousand police (civilian and military) patrol the riot zone. In reserve and on standby at several armories were eight thousand New York state guardsmen, including a black regiment. They were not needed, for the rioters were also exhausted. Over the next week life slowly returned to normal as the mayor lifted the liquor and traffic bans and city workers began a cleanup campaign. But the toll was costly. At least six persons, all black, were dead. Almost seven hundred were injured and nearly six hundred were arrested (most of whom were young adult males from a broad range of backgrounds), with property damage as high as $5 million.46

In the aftermath, the Amsterdam News echoed La Guardia when it declared that “we take our stand on the side of law and order, firmly asserting that those persons who violate the law ought to be arrested and punished.” Yet many officers routinely employed excessive force and expressed contemptuous attitudes. “Policemen can be efficient without being brutal!” it editorialized. Officers who were “efficient and understanding” would find the community supportive and sympathetic. But “Harlem will not be bullied, brow-beaten, or bull-dozed,” warned the newspaper.47

Langston Hughes also offered an ode to the woman whose arrest had led to the riot. In “The Ballad of Margie Polite,” he celebrated her refusal to accept her fate as a victim or go gently into the night. “If Margie Polite had of been white, she might not’ve cussed out the cop that night,” wrote Hughes. “In the lobby of the Braddock Hotel, she might not’ve felt the urge to raise hell.” But she was black and she had resisted arrest. In the process, she had become more than a footnote to history. “Margie warn’t nobody important before,” the poem continued. “But she ain’t just nobody now no more.”48

From a comparative perspective, the Harlem riots of 1935 and 1943 had similar roots and outcomes. In the words of Robert M. Fogelson, a noted urban historian, both were “spontaneous, unorganized, and precipitated by police actions.” Both featured looting aimed at property rather than people (unlike in Detroit). And both were, according to Fogelson, “so completely confined to the ghetto that life was normal for whites and blacks elsewhere in the city.” Even if the riots were a form of political protest, the prompt actions of black leaders and city officials effectively contained the violence and damage. “Nevertheless,” wrote Fogelson, who praised the “virtuoso performance” of La Guardia, “these efforts (and the riots themselves) indicated the inability of the moderate black leaders to channel rank-and-file discontent into legitimate channels and when necessary to restrain the rioters.” Thus the clashes of 1935 and 1943 were, in a sense, the “direct precursors” to the Harlem Riot of 1964.49

But for now what was more critical was how little had changed in the aftermath of the upheaval of 1943. More than three hundred thousand African Americans continued to face “obscene living conditions” as they crowded into substandard housing intended for seventy-five thousand. Harlem was still, asserted an article in Collier’s, “very inflammable, dynamically race conscious, emotionally on the hair trigger, doggedly resentful of its Jim Crow estate.”50 It remained ready to explode—all it would take was another spark.

Bayard Rustin was not in Harlem when it erupted in August 1943. At the time, he was on the road, tirelessly moving from city to city organizing and recruiting for Muste and Randolph. He was also working as a trainer for the newly formed Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which fellow FOR field secretary James Farmer had launched in an effort to promote racial justice through nonviolent resistance. Then in November Rustin received his draft notice and was arrested when he refused to report for civilian public service. He spent the next two years in federal prison, where he protested against segregated dining facilities, studied the ideas of Gandhi, and endured hunger strikes. He also faced homosexual misconduct charges, which delayed his release until 1946.51

The following year, Rustin and CORE executive secretary George Houser organized the Journey of Reconciliation, the first Freedom Ride to protest segregation in interstate travel. As a participant, Rustin was sentenced to a chain gang in North Carolina. But the arrest that shattered his life came in 1953, when he was taken into custody in Pasadena, California, and charged with lewd vagrancy for performing oral sex on two white men in the backseat of a car. It was not his first arrest for illegal sex, but it brought his homosexuality to public notice. After pleading guilty to a single charge of “sex perversion” (the official term for consensual sodomy at the time), he was fired from his position as director of race relations with FOR after twelve years of dedicated service.52

Feeling abandoned and adrift, Rustin struggled to make himself again acceptable and respectable in the eyes of the friends and allies he had once had. For the rest of his career, his sexual orientation would shadow him even more than his communist background. In 1953, he joined the War Resisters League (over the objections of Muste) and soon became executive director; four years later, Rustin was instrumental in persuading King to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. But in 1960 Congressman Powell (a board member and social conservative) forced Rustin to resign by threatening to expose his sexual orientation on the floor of Congress and feed false allegations to the press that he and King were lovers.53

While Rustin fought to restore his reputation, demographic change swept across many neighborhoods in New York in the 1950s, generating racial tension and conflict. Segregation, especially in housing and education, remained a serious problem. Economic factors—especially deindustrialization, automation, and discrimination—affected the workplace and job market, which in turn contributed to the depressed social conditions experienced by a large majority of African Americans in Central Harlem. And youth crime, often connected to the drug trade, was a growing concern of many residents.

The black migration to the North from the South, where the mechanization of cotton farming led to an exodus of millions of sharecroppers from rural areas, continued unabated after World War II. By 1950 more than one million African Americans lived in New York—a 30 percent increase since 1948. During the 1950s, almost half a million more blacks arrived, only to discover that the federal government and local banks preserved residential segregation by “redlining” neighborhoods and restricting loans. Meanwhile, more than a million whites departed for the suburbs of New Jersey, Long Island, and Westchester County, where blacks were usually not welcome. Even more whites might have left if not for the Lyons Law, which required city residency for municipal employees. But in 1960 the state legislature added a loophole for police officers, which enabled many of them to relocate and reinforced the sense in Harlem and Bed-Stuy that the NYPD was an outside force of occupation and oppression.54

The inflow of blacks and the outflow of whites changed the complexion of neighborhoods and boroughs. It also increased the pressure on housing as conditions worsened, especially in Harlem, where almost half of the buildings predated 1900. In an unpublished article on the first mental health institution in the area, the Lafargue Psychiatric Clinic, Ellison provided an almost hallucinogenic description of the plight of the community. “Harlem is a ruin,” he wrote, “[and] many of its ordinary aspects (its crimes, its casual violence, its crumbling buildings with littered area-ways, ill-smelling halls and vermin-invaded rooms) are indistinguishable from the distorted images that appear in dreams, and which, like muggers haunting a lonely hall, quiver in the waking mind with hidden and threatening significance.”55

Dr. Kenneth Clark offered a similar assessment in Dark Ghetto, his classic study of Harlem. “The most concrete fact of the ghetto is its physical ugliness—the dirt, the filth, the neglect,” he wrote. “The parks are seedy with lack of care. The streets are crowded with the people and refuse. In all of Harlem there is no museum, no art gallery, no art school, no sustained ‘little theater’ group; despite the stereotype of the Negro as artist, there are only five libraries—but hundreds of bars, hundreds of churches, and scores of fortune tellers. Everywhere there are signs of fantasy, decay, abandonment, and defeat.” Like Ellison, Clark saw a psychological dimension to the physical deterioration. “The only constant characteristic is a sense of inadequacy,” Clark observed of Harlem. “People seem to have given up in the little things that are so often the symbol of the larger things.”56

Here Clark’s analysis was not entirely fair or correct. Plenty of residents had not given up—on the contrary, they often engaged in political activism and mobilized against racial discrimination and segregation where they lived, worked, and went to school. In the 1930s, blacks in Harlem had participated in “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” demonstrations. In the 1940s, they had enthusiastically supported the successful campaigns of Powell for Congress and Benjamin Davis, a Harvard Law School graduate and staunch member of the Communist Party, for city council. They also picketed against Stuyvesant Town, a middle-class apartment complex that refused to rent to blacks despite the fact that the developer, Met Life, had received tax exemptions from the city. In the 1950s, a group of African American mothers who became known as the “Little Rock Nine of Harlem” pulled their children from three junior high schools as a protest against segregation.57

As overcrowding intensified, resentment over segregation deepened. In Harlem, where the number of residents had doubled since 1940, the number of apartments had not increased despite the construction of the Riverton Houses, a large middle-income housing development created by Met Life in response to the protests over Stuyvesant Town. White store owners, observed Jesse B. Semple (the Harlem character created by Langston Hughes), “take my money over the counter, then go on downtown to Stuyvesant Town where I can’t live, or out to them pretty suburbs, and leave me in Harlem holding the bag.” By 1952 blacks had finally won, after an unrelenting fight by a coalition of political and religious organizations, the right to live in the apartment complex—but only after it was fully occupied. Eight years later, when Lieutenant Gilligan was a resident, only a tiny handful of his neighbors were black.58

During the 1950s, the population of Harlem fell by 10 percent, mainly because poor blacks were moving to other ghettos like Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn. But a few middle-class black professionals were also starting to take advantage of the opportunity to relocate to the suburbs, among them Clark, who moved his family to Westchester in 1950 because it had better public schools than Harlem. “My children have only one life,” Clark said. “I can’t risk that.” It was, nevertheless, a difficult decision for the distinguished psychologist who with his wife produced the famous “doll study,” which documented the harmful effects of school segregation and influenced the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. “More than forty years of my life had been lived in Harlem,” Clark wrote. “I started school in the Harlem public schools. I first learned about people, about love, about cruelty, about sacrifice, about cowardice, about courage, about bombast in Harlem.”59

The departure of middle-class professionals like Clark coincided with the loss of decent-paying jobs for working-class residents. During the 1950s, deindustrialization came to New York as factories began to relocate to the South. Automation also invaded the service sector, leading to fewer opportunities for those with poor English or dark skin, little experience or limited skills. The first Latino borough president and member of Congress, Herman Badillo, arrived in New York from Puerto Rico with his mother in 1941. In the early 1950s, he was able to attend City College and law school by working as a pin boy in a bowling alley and as an elevator operator in an apartment building—both jobs threatened or eliminated by technology.60

Coincidentally, when Harlem erupted in 1964, both Mayor Robert Wagner and Congressman Powell were in Europe to attend a conference in Geneva on the impact of automation on cities. Meanwhile, blacks remained largely excluded from the skilled trades because labor unions and apprenticeship programs refused to accept them. Together, deindustrialization and discrimination ravaged Harlem. In 1962, Clark received a large grant from the President’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency, which believed that black teens posed a significant threat to urban peace. The grant funded the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU) project, which employed two hundred “associates” to conduct interviews and gather information about the community. Their research, which would become the statistical basis of Dark Ghetto, showed that most black families maintained a “marginal subsistence,” with a median income of $3,995 compared to $6,100 for white families.61

Compounding the inequity was the fact that blacks often paid more in rent than whites even though almost half the housing in Central Harlem was substandard compared to 15 percent in the city as a whole. Residential segregation led to higher rates of population density and left residents with fewer options about where to live. “Cruel in the extreme,” wrote Clark, is the landlord who, like the store owner who charges Negroes more for shoddy merchandise, exploits the powerlessness of the poor.”62

The perception of exploitation by white merchants—especially Jewish businessmen—was real and widespread. But whether it was accurate is more difficult to determine given that store owners of all races and religions had to operate in a “high-cost, high-crime, high-risk environment,” with narrow profit margins and limited returns on investment. Beyond debate, however, was the reality that African Americans owned or managed only 4 percent of Harlem businesses. By comparison, southern cities like Atlanta often had substantially greater numbers of black-owned businesses because of commercial segregation.63

Other measures of social distress were more obvious and less open to dispute by 1964. For example, the mortality rate for blacks as a whole remained 60 percent higher than for whites—73 percent for infants. Even the streets were, literally, less safe—in Central Harlem, a child was 61 percent more likely to get killed by a car than in other neighborhoods. And for black adults the unemployment rate was twice as high as for the rest of the city. Among young men eighteen to twenty-four, it was five times as high for blacks as for whites.64

The problem was likely to worsen, predicted Clark, as the number of teens rose and the number of jobs available to them fell. “The restless brooding young men without jobs who cluster in the bars in the winter and on stoops and corners in the summer are the stuff out of which riots are made,” he wrote. “The solution to riots is not better police protection (or even the claims of police brutality) or pleas from civil rights leaders for law and order. The solution lies in finding jobs for the unemployed and in raising the social and economic status of the entire community. Otherwise the ‘long hot summers’ will come every year.”65

“Brooding young men” on street corners were not new to Harlem. But in the two decades after World War II, the disappearance of jobs and, to a lesser extent, the departure of individuals like Clark weakened the social fabric of Harlem and contributed to the rise in social disorder. According to the NYPD, arrests of teenagers rose 60 percent between 1952 and 1957, with African Americans disproportionately implicated, although the statistics are open to interpretation and challenge.66 The figures nonetheless concerned the NAACP, which feared that conservatives might use them as proof of black criminality and evidence against racial integration. Executive secretary Roy Wilkins stated in 1959 that reducing youth crime was vital because “many of our enemies are using incidents of juvenile delinquency to buttress their fight against us and against desegregation of the schools.”67

Drugs—especially heroin—were a major cause of youth crime. In the 1950s, heroin claimed the lives of author Claude Brown’s brother and many of his friends. By the 1960s, “there were a lot more drugs than we ever saw in our life, a lot more burglaries, and a lot more assaults,” recalled Detective Sonny Grosso, a native of Harlem who also served there. “And that’s all tied to the addicts trying to get more money to pay for their drugs.” Dope pushing and gang banging—although the term was not yet invented—were rampant. According to a Harlem supervisor with the Youth Board, many leaders and members were heroin users, which led to internal conflict and gang disintegration as well as more crime and turf wars.68

At least half of New York’s thirty thousand addicts lived in Central Harlem, where narcotics arrests were more than ten times higher than in the rest of the city by 1964. “Property crimes skyrocketed to pay for habits, and then violent crimes followed, not only in the competition between dealers, but also in the disciplinary and debt-collecting functions of the gangs,” wrote a police historian. “Heroin created thousands of rich killers and millions of derelicts, whores, and thieves. In short, it created crime as we know it.”69

Dealing drugs was not, however, the only visible and profitable criminal activity in Harlem. Gambling was also widespread because “people were always looking for a way out,” recalled Detective Barney Cohen, who also served in Bed-Stuy. “The numbers game remains a community pastime; streetwalking still flourishes on 125th Street; and marijuana is easy to get,” Michael Harrington wrote in The Other America, his famous 1962 expose of urban and rural poverty. “These things are not, of course, natural’ to the Negro. They are by-products of a ghetto which has little money, much unemployment, and a life to be lived in the streets. Because of them, and because the white man is so ready to believe crime in the Negro, fear is basic to the ghetto.”70

Disillusionment and disenchantment were also pervasive according to a black journalist who testified before the state legislature in June 1963. “The mood of the Negro, particularly in New York City, is very, very bitter,” said Louis Lomax, who co-produced the documentary The Hate That Hate Produced about Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. “He is losing faith. The Negro on the streets of Harlem is tired of platitudes from white liberals.” Adding to the impatience and frustration was a sense of invisibility and inadequacy, because while Harlem simmered and suffered in the shadows, the national media spotlight shone brightly on the civil rights struggle in the South.71

In the North, African Americans now felt mounting pressure to become more active and visible in the freedom struggle. “Southern Negroes have shown bravery and should shame the Northern Negro,” said the entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. “They seem to have more spunk and backbone,” said a machinist in Harlem. The protests in Alabama were the turning point—the televised images had a searing impact, especially on urban teenagers. “For the black people of this nation,” wrote Rustin after a visit, “Birmingham became the moment of truth.” The civil rights movement, he believed, had reached a new stage. “The Negro masses are no longer prepared to wait for anybody,” he added. “They are going to move. Nothing can stop them.”72

With the civil rights bill facing an uncertain future in Congress, Rustin in July brought his idea for a march on Washington to the “Big Six” movement leaders—King, Randolph, Wilkins, Farmer, Whitney Young of the Urban League, and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). At a meeting in New York at the Roosevelt Hotel, Rustin called for a mass, nonviolent demonstration, which would require extensive planning and organization. But Wilkins immediately and strongly objected to him serving as director. “He’s got too many scars,” the NAACP leader said, citing Rustin’s flirtation with communism in the late 1930s, his prison term during World War II, and his arrest in Pasadena in 1953. “This march is of such importance that we must not put a person of his liabilities as the head.”73

Farmer, however, defended him, and after Randolph cleverly volunteered to serve as director (with Rustin as his assistant), Wilkins reluctantly agreed on the condition that Rustin remain in the background and avoid the limelight, which proved impossible. With less than two months to prepare, Rustin instantly set to work, hiring a staff, inventing policies, raising funds, and maintaining unity among the many organizations sponsoring the demonstration. It was the most intense period of his lengthy career, but he achieved a remarkable feat, earning forever after the title of “Mr. March” from his mentor, Randolph.

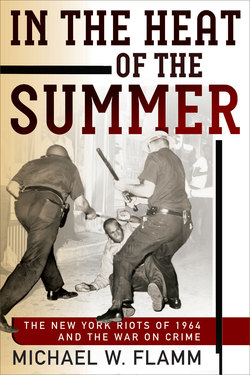

FIGURE 2. Bayard Rustin briefs reporters at the March on Washington in August 1963. Photo by Warren K. Leffler. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection (LC-U9-10332 frame 11).

An estimated quarter million people of all races and religions gathered in the nation’s capital in August to demand jobs, freedom, and passage of the civil rights bill. Behind the scenes, it was a tense time as debates erupted between the White House and civil rights leaders over the length of the demonstration, the tone of the speeches, the role of whites, even the dress of the participants. But in the end, after King had made his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, most Americans saw the March on Washington as a great triumph of the human spirit and a historic occasion when racial reconciliation at last seemed like a realistic possibility. The demonstration, Rustin believed, had also prevented violent unrest in northern cities by channeling hostile energy.74

A month later, the optimism generated by the March on Washington was shattered by the explosion of a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, where four little black girls waiting for the start of Sunday school were tragically murdered. For the slender and soft-spoken Clark, a liberal integrationist, it was a fateful moment. “The present battle for racial justice in America is in its showdown stage,” he wrote in Ebony. “Negroes and committed whites will either remove the last barriers to racial equality in America within the next year or two, or will witness a frightening and revolting form of racial oppression and moral stagnation.” No middle ground existed.75

But on his public television program The Negro and the Promise of American Life, Clark managed to strike a cautiously positive note after a series of conversations with Baldwin, King, and Malcolm X, with whom he was friendly even though they disagreed on most issues. “We have come to the point where there are only two ways that America can avoid continued racial explosions: one would be total oppression; the other total equality,” Clark concluded. “There is no compromise. I believe—I hope—that we are on the threshold of a truly democratic America.” In the coming year, the violence and unrest in New York would sorely test, if not dash, his faith in the future.76