Читать книгу In the Heat of the Summer - Michael W. Flamm - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

THE GROWING MENACE

Now no one knows how it started

Why the windows were shattered

But deep in the dark, someone set the spark

And then it no longer mattered

—Phil Ochs, “In the Heat of the Summer”

THURSDAY, JULY 16

The death of James Powell came almost instantaneously according to the autopsy report. The first .38 caliber bullet, perhaps intended as a warning shot, broke a glass panel in the outer door to the apartment building and smashed into the inner door of the vestibule. The second, perhaps intended to disarm Powell, went through the right forearm close to the wrist and then ripped into the chest, slicing the main artery above the heart and lodging in the lungs. It was the fatal wound. The third shot entered the abdomen just above the navel and severed a major vein. But according to the deputy chief medical examiner, Powell probably could have survived that injury if hospitalized promptly.1

“There was no evidence on the body of smoke, flame or powder marks,” the autopsy report stated, “thus showing that both bullets must have travelled more than a foot and a half before striking [the victim].” There were also no marks in the recently repaired sidewalk. Both findings cast doubt on the claim by some witnesses that Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan had fired the second and third bullets at close range while Powell was lying on the ground. But the forensic evidence would only arrive weeks later—too late to quell the rumors or quench the outrage felt by many in the black community.2

On the final morning of his young life, Powell said goodbye to his mother Annie at 7:30 A.M. and left his home in the Soundview Housing Project, a lower-income apartment complex in the Bronx. At age fifteen he was a relatively small and slight youth, standing five feet six inches tall and weighing 122 pounds. An only child and a ninth-grader at nearby Samuel Gompers Vocational High School, Powell was taking voluntary remedial-reading classes at Wagner Junior High School for the summer term, which had started nine days earlier.3

Since the death of his father Harold three years earlier, Powell had begun to get into scrapes with the law, including arrests for armed robbery and breaking a car window. Twice he was also charged with trying to board a subway or bus without paying the fare. None of those arrests had led to convictions. But according to the FBI, Powell ran with a gang and had suffered a knife wound in his right leg that required hospitalization. That might explain why he gave two knives, one with a black handle and one with a red handle, to Cliff Harris and Carl Dudley, two other boys who joined him on the way to the subway on that fateful morning.4

Neighbors had a mixed view of Powell. Some believed that he was a good kid and doubted that he would have sought serious trouble. Others contended that he was a troubled youth who “liked to get high on whiskey” and was beginning to develop a wild streak. From interviews with school officials and social workers, the FBI learned that Powell was a chronic truant who had been absent thirty-two days in the spring term, which was why he needed to attend summer school. When he was present, fellow students accused him of bullying them, stealing from them, and starting fights—even in the guidance office.5

Powell and his friends were part of a group of about one hundred students who were waiting for classes to begin at 9:30 A.M. Some were standing near the entrance to the school. Others were leaning on cars or sitting on stoops across the street where a superintendent named Patrick Lynch, a stocky thirty-six-year-old Irish immigrant with a strong brogue, was watering the plants, flowers, and trees in front of the apartment buildings at 211 and 215 East 76th Street.6

Lynch and his white tenants had little patience for the summer school students, most of whom were black. The Yorkville neighborhood had few minorities, and during the regular term Wagner Junior High School, which had not previously hosted a summer school session, was roughly half white, a quarter African American, and a quarter Puerto Rican. Those students were not a problem according to the superintendent. “They sit on the stoops to eat lunch and I don’t pass any remarks,” he told a reporter later, in what seemed like a partial confession. “They clean up. They’re good kids.”7

Not so the kids who attended summer school. In Lynch’s eyes, they were rude and loud, creating problems for everyone, especially local merchants, and leaving litter everywhere. He repeatedly complained to the school principal, Max Francke, a mild-mannered, white-haired man who was not sympathetic and tended to side with the students. The building superintendent also lodged more than twenty complaints with the police, who were equally unresponsive. “The other day, my wife was on the street when a couple of kids went for each other with bottles,” Lynch said later in a tone of sadness and regret. “My wife went upstairs and called the police, but they never came. They always come after something serious. But why couldn’t they come before? Then this would never have happened.”8

What happened on July 16 at 9:20 A.M. in front of 215 East 76th Street was unclear and contested, both then and now. The grand jury, which by law automatically reviewed every fatal police shooting in New York, heard testimony from “all known” witnesses, including those brought to the attention of the district attorney by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Of the forty-five interviewed, fifteen were teenagers who were friends or acquaintances of Powell. Among them were his buddies Harris and Dudley. But the eyewitnesses offered conflicting testimony about whether Powell was armed or had attacked Gilligan, perhaps because a repair truck parked in front of the building obstructed their views. Whether the officer had issued a warning or identified himself was also contentious.

Despite the controversy surrounding the incident, the basic cause of the deadly confrontation was not in dispute. According to Lynch, he was washing the sidewalk with a hose at 9:15 A.M. when he repeatedly asked a group of students who were standing near the steps to move so that they would not get wet while he watered some flowers on a fire escape above them. They refused and then claimed that the superintendent had sprayed them with water after calling them “dirty niggers” and threatening to “wash the black off you.”9

Lynch denied the accusation, but Francke backed the teens, asserting that the hosing was done with “malice aforethought.” The principal also accused the superintendent of poor judgment and blamed him for the tragedy. True or not, the incident was laden with overtones from the demonstrations in Birmingham a year earlier, when police officers turned fire hoses and water cannons on black children. Now the students began to retaliate by throwing bottles, trash, and metal garbage can lids at Lynch, who quickly darted inside the building. Yet by then it was too late—the confrontation had already attracted the attention of Powell, Harris, and Dudley across the street.10

“I am going to cut that [expletive],” said Powell, who asked Dudley for the knife with the red handle. When he pretended not to have it, Powell asked Harris for the knife with the black handle. “What do you want with it?” asked Harris. “Give it to me,” said Powell, who added “I’ll be back.” So Harris gave the knife to Powell, who started to cross the street. A girl pleaded with him and tried to restrain him, but he brushed her aside and, with the knife in his right hand, headed up the steps screaming “hit him, hit him, hit him.”11

At that moment, Gilligan emerged from the Jadco TV Service Company next door. For the officer, a solid man who stood more than six feet tall and weighed two hundred pounds, the morning was supposed to be quiet and uneventful. The plan was to get a radio fixed at a shop he knew from previous duty in the precinct. A thirty-seven-year-old resident of Stuyvesant Town, a middle-class, virtually all-white apartment project on the East Side, he was off duty and out of uniform, although he had his badge and revolver with him as department regulations required. Like all officers he was obligated to stop crime, arrest offenders, and protect life as well as property at all times.

On this day, Gilligan was assigned to the 14th Inspection Division in Brooklyn, where he was a decorated officer who had joined the force after serving in the Pacific during World War II. In seventeen years on the job, he had received nineteen citations, represented by impressive rows of enameled bars above the gold badge on his dress uniform. He had four citations for disarming suspects without firing his weapon and two for disabling suspects with his revolver (he had never killed anyone until Powell). In 1958, he had fought for his life with a man on a rooftop; despite a broken wrist, Gilligan managed to shoot him as he fled. In 1960, he was able to wound a youth in the right shoulder who was vandalizing cars outside Stuyvesant Town and had broken two fingers on the officer’s gun hand with a fire nozzle.

Gilligan also had numerous citations for saving lives. He had, wrote two reporters, “rescued women and children from a fire, saved an unconscious man by first aid, stopped a man from a suicidal jump, rescued an unconscious man trapped in a basement after an explosion, and used mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to revive a woman who had attempted suicide by swallowing barbiturates.” By many accounts, Gilligan was a hero cop. By many others, he was a “Killer Cop” whose face was soon plastered on “Wanted for Murder” posters across Harlem.12

The histories of Powell and Gilligan were, of course, immaterial in a court of law. Powell’s background had no direct bearing on his actions that day. Gilligan’s record was also irrelevant—good officers make bad shootings and vice versa. But in the court of public opinion, which the civil rights movement and press coverage had greatly influenced, the information mattered deeply. As in all controversial police incidents with racial overtones, many whites and blacks fit the “facts” as they understood or perceived them into a simplistic narrative with an innocent or menacing victim and an upright or brutal officer.

When the owner of the appliance store told him that Thursday morning of the trouble with the summer school students, Gilligan had no desire to get involved. But the officer would not have a choice. As the merchant watched through the front window of the shop, the teens begin to hurl objects at Lynch and there was a loud crash as glass shattered. At that point Gilligan ran out of the store, removing from his trouser pockets his badge with his left hand and his revolver with his right hand. He was standing at the bottom of the stoop when Powell turned from the entrance to the building and headed back down the steps to the street.13

“Stop, I’m a cop,” Gilligan yelled. “Drop it.” But Powell kept coming down the stairs. With the knife in his right hand, he tried to strike at Gilligan, who had a split second to make a life-or-death decision. With his heart pounding and adrenalin pumping, he fired a shot. The teen slashed again at the officer, who blocked Powell and pushed him away. The knife, however, sliced Gilligan’s arm and when the youth raised it once more, the officer fired again. The bullet struck the teen’s wrist and deflected into his chest, but his forward momentum continued. And so Gilligan stepped back and fired a third time into the abdomen of Powell, who collapsed on the sidewalk, face down, his blood pooling underneath him.14

Seeing Powell on the ground with his body parallel to the curb, his friend Harris raced across the street. “I ran over to where he was and got down on my knees next to him and said, ‘Jimmy, what’s the matter?’” he recalled. But there was no response except for a trickle of blood from Powell’s mouth as he tried to spit. So Harris turned his attention to the officer, who was looming over them with a gun at his side, and asked him if he could call an ambulance. “No, this black [expletive] is my prisoner,” Gilligan replied according to Harris. “You call the ambulance.”15

From the corner candy store, the teen phoned for help as screams started to come from the crowd of students in front of the school. At the same time, Francke stepped outside, saw the body, and instructed his secretary to call an ambulance. But by the time it arrived Powell was dead. Later, a teacher found the black-handled knife, which Harris subsequently identified, in a gutter between parked cars about eight to ten feet from the body.16

That is how most of the adult witnesses interviewed by the grand jury saw the incident, with minor discrepancies such as the precise words Gilligan had used when confronting Powell. Among the adult witnesses, most of whom were white, were a bus driver, a truck driver, a nurse, a priest, two merchants (including the owner of the repair store), five teachers, and eight passersby. But that is not how most of the fifteen black students interviewed perceived the altercation. They maintained that Gilligan had not identified himself as a police officer, had given no warning, and had fired two shots into Powell’s back while he lay wounded on the sidewalk. Most of the students also claimed that Powell was unarmed and unthreatening.17

“I saw the boy go into the building and he didn’t have any knife then,” said a teenage girl. “When he came out, he was even laughing and kind of like running and the cop was on the street going into the building and then he shot him.” Even if she was wrong about the knife, it was understandable. In Harlem, it was common knowledge that police officers routinely carried throwaway knives because they risked disciplinary or criminal charges if they used deadly force against an unarmed assailant. The standard police jacket, which Gilligan was not wearing at the time, even had a concealed breast pocket—ostensibly for that purpose. Although it seems likely that Powell had a knife, especially since the shooting took place in broad daylight before numerous eyewitnesses, it is easy to see why so many blacks in New York would reach the opposite conclusion.18

At the crime scene, more trouble was brewing. As Gilligan was whisked to Roosevelt Hospital to get his arm bandaged (Lynch was also treated there for a possible fracture of his left hand, which was struck by a bottle), the students kept converging despite repeated warnings from police. The arrival of a news photographer caused the confrontation to escalate. “This is worse than Mississippi,” yelled female students in reference to the three missing (and presumed dead) civil rights workers from CORE who had disappeared in June during the “Freedom Summer” campaign to register black voters. “It looked bad,” said Francke. “I borrowed a bullhorn and tried to calm the youngsters but it was impossible to quiet the crowd.”19

As the police issued five riot calls, more than one hundred officers arrived in steel helmets. Eventually, the disturbance ended after ninety minutes without more violence or arrests, although three young women were briefly taken into custody and then released. But as the crowd dispersed emotions continued to run high. At the 77th Street entrance to the Lexington Avenue subway station, a group of fifty black students ransacked a newsstand, scattering papers and candy, and threatened a white motorman with a screwdriver. Another group slapped a white woman on the street and hurled a flower pot through the window of a flower store, terrifying the owner. “Are they going to let that cop go free?” challenged a teenage girl.20

Francke, the school principal, defended the students in the aftermath. “These children are not hooligans,” he said. “They’re dedicated to improving themselves and we never had any trouble with them.” A deli owner agreed. “This is a racial problem,” he observed. “They cry because they feel there’s no justice for them. Whether they’re right or wrong, we have to change their minds.” But other white residents of Yorkville disagreed. “I never thought I’d see the day when I’d be afraid to walk in my own neighborhood in broad daylight,” said an older man, “but when I see these kids coming I duck into the nearest doorway.” And a retired woman expressed resentment: “They hang around our hallways. When we tell them to leave they act as if we are prejudiced against them. We just don’t like having garbage and noisy people in our home.”21

Within hours of the incident members of CORE’s national office and East Side chapter were holding an impromptu press conference at the corner of 77th and Lexington. In front of newspaper reporters and television cameras, they spoke of police brutality and the pressing need for an independent civilian review board not composed of police officials to investigate the shooting. The NAACP also demanded an immediate inquiry by the district attorney. In response, Deputy Chief Inspector Joseph Coyle promised a prompt investigation, but asserted that Gilligan had acted in self-defense.22

The man of the hour, however, was silent and out of sight. Had Gilligan made a public statement in the immediate aftermath of the Powell shooting, it is conceivable that some of the rage and anger spreading across Central Harlem might have dissipated. But on the advice of counsel he was already taking a low profile and avoiding the media spotlight. Not so the presidential nominee of the Republican Party, who at that moment was preparing to deliver the biggest speech of his political life at the Cow Palace in San Francisco.

A year before the Powell shooting, Barry Goldwater had anticipated that racial unrest would spread from the South to the North. “I predict,” he told an interviewer in July 1963, “that if there is rioting in the streets it’ll occur in Chicago, Detroit, New York, or Washington, probably to a greater extent than it will occur in the southern cities.”23 Like most conservatives, he believed that the civil rights movement had contributed to urban black violence. In a letter to a friend, Goldwater wrote that “I am somewhat fearful of what might happen in some of our large northern cities … if this type of fire-eating talk continues among the Negro leaders and those whites who would use them only as a means to gain power…. I am afraid we’re in trouble.”24

Precisely which black leaders and white liberals Goldwater had in mind is not clear. But like millions of other Americans, he had seen the newspaper photos and watched the television broadcasts from Birmingham, Alabama, where Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor had jailed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in May and then unleashed police dogs and water cannons on black children marching for freedom and justice. In June, Goldwater had listened to John Kennedy speak to the nation about the pressing need for immediate action on civil rights.

“We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” said the president, only hours after segregationist Governor George Wallace had made his infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” in a vain attempt to prevent two black students from registering for classes at the University of Alabama. “It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.” Kennedy also expressed concern at how prejudice and discrimination against African Americans discredited the image of the United States in the eyes of the world.25

Like Goldwater, Kennedy saw a threat to order and security—white liberals and conservatives feared black unrest, although they differed on the causes of it. “The fires of frustration and discord are burning in every city, North and South, where legal remedies are not at hand,” the president observed. “Redress is sought in the streets, in demonstrations, parades, and protests which create tensions and threaten violence and threaten lives.” To preempt the danger, he asked Congress to enact legislation making public accommodations such as hotels and restaurants, stores and theaters, open to all regardless of race.26

The introduction of the civil rights bill placed Goldwater in a challenging but promising political position. Kennedy’s action had led more southern whites to reconsider their allegiance to the Democratic Party. But could Goldwater win their votes without becoming known as a racial extremist and losing the support of white moderates elsewhere in the country?

There is no substantiated evidence that the senator was prejudiced in his private life, that he ever made racist remarks or told racist jokes. By the same token, Goldwater was clearly and strongly in favor of gradual and voluntary integration. In his family’s department stores, he had welcomed black customers and hired black employees. In his hometown of Phoenix, Goldwater was a founding member of the National Urban League chapter and had played a major role in promoting the integration of schools and restaurants. And in his Air Force Reserve unit he had led the fight against segregation. Although he tolerated the presence, knowingly or not, of racial and religious bigots at campaign events in the South, he never spent a night in a hotel that refused to provide service to blacks.27

But in his public life Goldwater had voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and anti–poll tax legislation in 1960 and 1962. Now he opposed the civil rights bill on the stated grounds of property rights and states’ rights. With the assistance of ghostwriter L. Brent Bozell, Jr., the brother-in-law of National Review publisher William F. Buckley, he wrote Conscience of a Conservative. In the best seller, which sold more than three million copies, Goldwater objected to forced integration and stated that he was not willing to impose his racial views on “the people of Mississippi or South Carolina…. That is their business and not mine. I believe that the problem of race relations, like all social and cultural problems, is best handled by the people directly concerned.”28

In Goldwater’s mind, legislation in general—and laws imposed by Congress in particular—had little chance of changing people’s hearts, especially on a matter as personal as race. In Goldwater’s heart, he most feared an expansive and intrusive federal government: the United States would become a police state where the executive branch promoted a minority’s rights at the expense of the majority’s freedoms. That Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia were already police states for African Americans was seemingly lost on the Arizona senator.

Goldwater instead worried that property owners would no longer have the right to rent or sell to whomever they wanted. Small businesses would no longer have the right to offer or deny service to whomever they wanted. States would no longer have the right to pass or enforce laws that reflected local values or customs, and employers would no longer have the right to hire or fire whomever they wanted. Free association would become subject to governmental regulation. The Founding Fathers’ dream of limited government and local control would become a constitutional nightmare.

Across the nation, tens of millions of white Americans agreed with Goldwater. But could he harness their support and use it to capture the Republican nomination in the face of strong opposition from New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a prominent supporter of civil rights? Was the “white backlash” against the freedom movement strong enough to sweep him into the White House? By 1963 conservatives were hard at work trying to convince Goldwater to pursue the presidency. But the senator was playing coy and keeping his cards close to his chest. When he met with supporters in January, Goldwater was firm: “Draft, nothin’. I told you I’m not going to run. And I’m telling you now, don’t paint me into a corner. It’s my political neck and I intend to have something to say about what happens to it.”29

But in fact he was already considering possibilities and weighing options. In May he received an unexpected political gift when the front-runner Rockefeller, who had divorced his wife the previous December, announced that he was remarrying. His bride was Margaretta “Happy” Murphy, a campaign volunteer and young mother who only a month earlier had divorced her husband. Most shockingly, she had also surrendered custody of their four small children, who ranged in age from eleven years to eighteen months.

The news generated outrage in conservative circles. “A man who has broken up two homes is not the kind we want for high public office,” declared Phyllis Schlafly, an Illinois activist whose self-published book about the Goldwater campaign, A Choice Not an Echo, became a sudden and surprise best seller. “The party is not so hard up that it can’t find somebody who stuck by his own family.” Overnight, the polls reversed and Goldwater surged into the lead among Republicans, despite gaffes such as his comment on an ABC-TV news program that the United States could block the flow of weapons from North Vietnam to the Communist guerrillas in South Vietnam by using low-grade atomic weapons to defoliate the dense jungles and expose the supply routes to aerial bombardment.30

Although reluctant to declare his candidacy openly, Goldwater was looking forward to running against Kennedy, a political foe and personal friend whom he had come to know and like during their years in the Senate together. But on November 22, 1963, the assassination of the president may also have killed Goldwater’s hopes for the White House. Suddenly, he was faced with a race for which he had no zest and in which he had little chance, since his opponent, Lyndon Johnson, could now campaign as the torch bearer for his mourned predecessor.

Goldwater despised Johnson, whom he saw as a “treacherous” opportunist and blatant “hypocrite” who had never “cleaned that crap off his boots.” Moreover, conservatives had to endure harsh criticism from the national media, which claimed that right-wing elements in Dallas were responsible for the “climate of extremism” that had somehow contributed to the assassination. Goldwater nevertheless announced his candidacy from his home in Scottsdale, Arizona, in January 1964. “I will not change my beliefs to win votes,” he pledged. “I will offer a choice, not an echo.”31 It was a promise he would keep—to his detriment after the nomination.

The campaign got off to a rocky start in New Hampshire in March, when Goldwater lost to former Massachusetts senator and New England favorite son Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., Nixon’s running mate in 1960 and by then the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. Of greater significance than the primary defeat was Goldwater’s decision to make law and order a centerpiece of his presidential campaign. It was a momentous choice by the candidate, who had guaranteed voters a clear alternative.

The issue of law and order would help Goldwater win the Republican nomination, but in 1964 he could not ride it into the White House because of his reputation as a racist and extremist who might trigger a nuclear war. Public fear over “crime in the streets” also had not yet reached a critical level. Law and order would nonetheless become a powerful tool for conservative candidates for decades. And it would help make public support for punitive measures by the police and the courts an enduring foundation of the coming crusades against crime and drugs.

Goldwater was not the inventor or originator of law and order. Since Reconstruction in the 1860s and 1870s southern whites had blamed black criminality on the end of slavery and the beginning of integration. By the 1920s, the Great Migration of African Americans had led to similar fears among northern whites. In the 1940s and 1950s, the rise of the modern civil rights movement led conservatives in Congress to warn repeatedly of the great threat racial integration supposedly posed to public safety. In the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1960, for example, Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina declared that it would lead to a “wave of terror, crime, and juvenile delinquency” in the South as earlier state laws had in the North. Democratic Senator James Eastland of Mississippi likewise asserted that “law enforcement is breaking down because of racial integration” and claimed that the unsafe streets of New York were clear evidence.32

But it was Goldwater who introduced law and order to presidential politics in March 1964, when he charged that crime and riots—which conservatives continually if inexactly conflated—ran rampant in America’s streets. He refused, however, to place the blame on racial integration, unlike Thurmond, Eastland, and Wallace, who made law and order the focus of his presidential campaign when he entered Democratic primaries later in the spring. Goldwater instead asserted that the fault lay with the widespread practice of nonviolent protest, which in turn had led to disrespect for authority. The Arizona senator also ascribed guilt to white liberals like President Johnson, who in a crass and cynical bid for black votes had condoned and even applauded demonstrators when they violated what they viewed as unjust and immoral laws.

“Many of our citizens—citizens of all races—accept as normal the use of riots, demonstrations, boycotts, violence, pressures, civil disorder, and disobedience as an approach to serious national problems,” thundered Goldwater at the University of New Hampshire, where he promised to restore law and order. Passage of civil rights legislation, he predicted, would not lead to lower tensions and less crime—as white and black liberals had asserted for decades—but only to more bloodshed and fewer restraints on individual behavior. Like most conservatives, he saw black criminality as a result of immorality, not prejudice.33

Goldwater used law and order to blend concern over the rising number of traditional crimes—robberies and rapes, muggings and murders—with unease about civil rights, civil disobedience, and civil unrest. If the fear factor reached a critical level, conservative politicians, pundits, and propagandists could emphasize that opposition to crime and violence, not support for discrimination and segregation, was the reason for their resistance to the freedom struggle. Of course, liberals could with justification respond that the calls for law and order frequently rested on racial prejudice. Civil disobedience was often the only recourse left to black demonstrators denied basic freedoms and confronted by white officials who exploited the law or white extremists who defied it. But what made law and order such a potentially potent political weapon for conservatives was that they could turn it into a Rorschach test of public anxiety and project different concerns to different people at different moments.

More fundamentally, Goldwater offered a cogent view of a complicated and threatening world by contending that the loss of security and order was merely the most visible symptom and symbol of the failure of liberalism. In his view, the welfare state had squandered the hard-earned taxes of the deserving middle class on wasteful programs for the undeserving poor. These programs had in turn aggravated rather than alleviated social problems by encouraging personal dependence and discouraging personal responsibility. They had also raised false hopes and expectations on the part of the disadvantaged. “Government seeks to be parent, teacher, leader, doctor, and even minister,” he argued at a New Hampshire high school. “And its failures are strewn about us in the rubble of rising crime rates, juvenile delinquency, [political] scandal.”34

It was a powerful, if premature, indictment of the War on Poverty that Johnson hoped to launch and Goldwater wanted to forestall. But for the moment law and order enabled the Arizona senator to focus on what he and other conservatives claimed were the negative consequences of civil rights without directly opposing what had become a moral imperative to most liberals and many moderates. In the primary campaign, the issue might also help him broaden his appeal in southern and western suburbs. And by enhancing Goldwater’s popularity with working-class and lower middle-class whites, especially ethnic Catholics in northern cities, law and order might facilitate a successful challenge in the general election, if he could first claim the Republican nomination.

In April the campaign continued to stumble, but in May it gained momentum and delegates, including 271 of 278 from southern states. At a rally in Madison Square Garden before eighteen thousand enthusiastic supporters, Goldwater said he supported the right to vote but not the effort to legislate integration, calling it a “problem of the heart and of the mind.” He added that “until we have an Administration that will cool the fires and the tempers of violence, we simply cannot solve the rest of the problem in a lasting sense.” The comment met with scorn from Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP. He warned that the patience of blacks was wearing thin as the civil rights bill remained stalled in Congress. “If [our] pleas continue to be met with sophistry and antebellum oratory there will certainly be violence in the streets and elsewhere,” he predicted. “There is nothing left. There is no place to turn.”35

At a Memorial Day rally in Riverside, part of Goldwater’s all-out effort to defeat Rockefeller and win the critical California primary, he again rejected the liberal claim that passage of the civil rights bill would reduce black crime and promote racial harmony. “Some wobbly thinkers think that laws will stop you from hating, laws will make you generous,” he said with disdain. “But when I read about street crimes, about hatred covered with blood, I ask what’s happening to the land of the free.” Three days later, he attracted 51 percent of the vote and clinched the Republican nomination. Southern California had provided the vital votes. In morally traditional Orange County, Goldwater swamped Rockefeller, whose new wife had given birth the weekend before the election, by an almost two-to-one margin. Now it was on to the convention—but first the senator had to return to Washington, where the debate over the civil rights bill had reached a climax.36

Back in February the House of Representatives had overwhelmingly approved the measure. But in the Senate a core group of southern Democrats had blocked it. After a seventy-five-day filibuster, the longest in history, the Senate took a cloture vote on June 10. Supporters of the bill needed sixty-seven votes to halt debate; in the end, they received seventy-one, including the “aye” of Democratic Senator Clair Engle of California, who was in a wheelchair and had to point to his eye because he could not speak due to a brain tumor.37

On June 18, Goldwater was one of twenty-seven senators—only six of whom were Republicans—to vote against the Civil Rights Act, which Johnson signed into law on July 2. The racial question was “fundamentally a matter of the heart,” Goldwater declared on the floor of the Senate. “The problems of discrimination cannot be cured by laws alone.” He added that “if my vote is misconstrued, let it be, and let me suffer its consequences…. This is where I stand.”38

As anticipated, Goldwater’s vote attracted harsh criticism from liberals. But he received strong praise from conservatives like Ezra Taft Benson, former secretary of agriculture in the Eisenhower administration and later president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Like Goldwater he agreed that the bill would lead to more violence, but he blamed communists—not liberals. “The plans made some years ago for the use of the Negroes in stirring up strife and contention, if not civil war, is being carried out effectively,” warned Benson.39

At the Republican Convention in San Francisco, most of the delegates shared Goldwater’s opposition to civil rights and support for law and order. On July 14, the second night, Dwight Eisenhower arrived and, in a lastminute departure from his prepared text, warned of the danger posed by crime. “Let us not be guilty,” he said, “of maudlin sympathy for the criminal who, roaming the streets with switchblade knife and illegal firearms seeking a helpless prey, suddenly becomes upon apprehension a poor, underprivileged person who counts upon the compassion of our society and the laxness or weaknesses of too many courts to forgive his offense.” As the journalist Theodore White observed, the former president was “lifting to national discourse a matter of intimate concern to the delegates, creating there before them an issue which touched all fears, North and South. The convention howled.”40

Two nights later, on July 16, Goldwater again brought the convention to a fever pitch. In no mood to offer conciliatory words to the moderates who had called him an extremist and sought to block his nomination even after he had secured a majority of the delegates, he made it clear that conservatives were now in charge. “Those who do not care for our cause, we don’t expect to enter our ranks in any case,” he declared. And then he offered the aphorism for which he is best remembered. “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” he stated. “And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

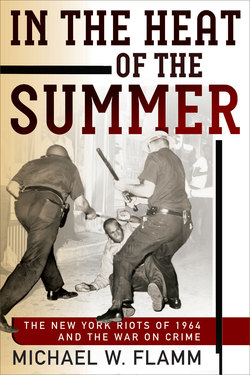

FIGURE 1. Senator Barry Goldwater addresses the Republican Convention on July 16 and accepts the presidential nomination. © Bettmann/CORBIS.

A reporter in the auditorium was stunned: “My God, he’s going to run as Barry Goldwater.”41

But while journalists and historians subsequently focused on that phrase and moment, the part of the speech that ignited and united the delegates was the nominee’s invocation of law and order. Demanding in loaded language with racial overtones that public security “not become the license of the mob and of the jungle,” Goldwater blamed the Democrats for allowing crime to flourish as the more than thirteen hundred delegates, only fifteen of whom were black (none of them from the South), roared their approval.42

“The growing menace in our country tonight, to personal safety, to life, to limb and property, in homes, in churches, on the playgrounds and places of business, particularly in our great cities, is the mounting concern—or should be—of every thoughtful citizen in the United States,” he growled as the crowd hooted and hollered. “History shows us, demonstrates that nothing, nothing prepares the way for tyranny more than the failure of public officials to keep the streets from bullies and marauders.”43

In the final draft of his nomination speech, Goldwater had scrawled in the margins even stronger and more personal language, which he opted not to deliver. “Our wives dare not leave their homes after dark,” he wrote. “Lawlessness grows. Contempt for law and order is more the order than the exception.”44 Later he would use these lines when he gave his first postconvention speech in Prescott, Arizona, in September.

But for now Goldwater retired to his headquarters at the Mark Hopkins Hotel, where he answered questions from reporters and stressed his determination to make law and order a centerpiece of his fall campaign. “I think law, and the abuse of law and order in this country, the total disregard for it, the mounting crime rate is going to be another issue” he said, “at least I’m going to make it one because I think the responsibility for this has to start someplace and it should start at the Federal level with the Federal courts enforcing the laws.”45

Goldwater then cited a New York case in which a woman who had defended herself with a knife against a rapist was facing possible criminal charges while her assailant would probably go free. “That kind of business has to stop in this country,” he said, “and as the President, I’m going to do all I can to see that women can go out in the streets of this country without being scared stiff.” In fact, the rates of murder and rape in Phoenix were substantially higher than in New York, as Democrats would hasten to note in coming days.46

For the moment, however, the top Democrat was silent, almost certainly by design. During a light day of staged domesticity, Johnson in the morning visited the Tidal Basin, where he and Lady Bird viewed the Darlington Oak Tree, which she hoped to plant on the South Lawn of the White House. In the afternoon, the two took a carefully orchestrated stroll from the White House to Decatur House and then through Lafayette Park. In the evening, the First Lady appeared while the president was reading a newspaper. “What time are you going to eat dinner?” he asked. “The minute you are ready,” she replied. “What are your plans for later?” Johnson said he had some mail to sign and would join her in thirty to forty minutes.47

But first the president had one more call to make—to former Senator Ernest “Mac” McFarland, chairman of the Arizona delegation to the Democratic Convention. His surprising loss to Goldwater in 1952 had lifted the conservative Republican to national prominence—but had also opened the door for Johnson, who at forty-six became the youngest Majority Leader in American history when the Democrats regained control of the Senate after the 1954 elections. Now the two old colleagues shared reminiscences as they prepared to watch Goldwater accept the GOP nomination in a few hours.

“Gosh, this fellow you sent up here has caused us a lot of problems,” said the president. “Well, I know what you’re talking about,” chuckled McFarland, who had failed to unseat Goldwater in 1958 despite winning races for governor in 1954 and 1956. “He caused me some.” Then the two men got down to business: Would the president like him to make a statement to the press about Goldwater, given their history? McFarland thought it was a bad idea, but said “if you want me to make one I will and I’ll say whatever you want me to say.” Johnson demurred since he had already informed reporters that he would make no comment at this time: “I just told ’em I was going on sawing my wood and doing my work.”48

But the president was clearly annoyed by Goldwater’s charges. “He’ll call me a faker and he called me a phony and a lot of ugly names, but I didn’t have anything to say about him,” Johnson maintained. “And so I noticed he backed up this morning and said he didn’t want to engage in any personalities.” McFarland was sympathetic—and skeptical. “Well, last night he said there might be a few brickbats,” he noted. Johnson, however, remained adamant: “I’m just going to let him go and we’re going to give him lots of rope.”49

After dinner with the First Lady the president retired for the evening. Presumably, he watched Goldwater’s speech, which began at 11:20 EST on Thursday night, but no aides were present to record his immediate reaction. On Friday morning, as organized protests began in New York, Johnson traveled to his ranch outside Austin for the weekend. From there he phoned special assistant Bill Moyers, who at his request read back to him Goldwater’s already-notorious claim that extremism in the defense of liberty was no vice. “Well, extremism to destroy liberty is,” responded the president. Offering a window into how he viewed the speech, he informed Moyers that he wanted to issue “a balanced statement, not a vicious, violent Goldwater one.”50

Back in the White House, Goldwater’s address and comments to the press about crime and race set off alarm bells. In private, aides worried about an anti–civil rights reaction by whites. “I am disturbed about the continued demonstrations and what I see on radio and TV,” wrote an official. “I am convinced that a great deal of the Negro leadership simply does not understand the political facts of life, and think that they are advancing their cause by uttering threats in the newspapers and on TV. They are not sophisticated enough to understand the theory of the backlash unless they are told about it by someone whom they believe.” Another staffer urged Johnson to initiate a dialogue with Wilkins, CORE leader James Farmer, and other civil rights leaders as soon as possible, which the president would do the week after Harlem exploded.51

But for now Johnson expressed optimism in public. On July 18, the Saturday after the Republican Convention, the president stated at a news conference on his Texas ranch that the United States did not possess, need, or want a national police force, which would contradict Goldwater’s belief in limited government. “If we are going to give the federal government the responsibility for all law enforcement, in the cities and towns, even here in the hill country,” Johnson said, “I would think that the people would believe that it would do more than anything else to concentrate power in Washington.”52

The response was carefully crafted and fully indicative of the confidence the president felt as the polls showed him with a large lead. But at that moment he had no inkling of the storm brewing in Central Harlem.