Читать книгу In the Heat of the Summer - Michael W. Flamm - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

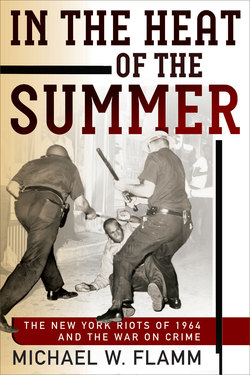

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

“Come on, shoot another nigger!”

With tears streaming down her face, the black teenager taunted a helmeted phalanx of New York City policemen. Amid a barrage of books and bottles from two hundred black students, the officers struggled to maintain order outside Robert F. Wagner Junior High School on East 76th Street in Upper Manhattan. The only serious casualty at the scene was the sole black patrolman, who suffered a concussion when hit in the head by a can of soda. He remained on duty for more than an hour before collapsing, and was raced unconscious to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he eventually recovered.1

The heated protests spontaneously erupted minutes after Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, a white off-duty officer in civilian clothes, fired three shots and killed a black student, fifteen-year-old James Powell, on July 16, 1964. The fatal confrontation followed an earlier altercation that Thursday morning between a white superintendent and black teenagers in front of an apartment building across the street from the school. But tensions were already high from a publicized series of violent crimes featuring black assailants and white victims.2

At that instant, three thousand miles away in San Francisco, weary aides to Barry Goldwater were putting the finishing touches on his acceptance speech to the Republican Convention. At the Cow Palace the previous night Goldwater had received the greatest prize of his political career—the presidential nomination. Now he would announce to the excited delegates in the arena and the American people watching on television that the conservative moment had arrived and what the nation needed was law and order.

Fourteen hours after Powell bled to death on the sidewalk, Goldwater strode to the podium as the band played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and red, white, and blue balloons fell from the rafters. Grim and stern, with black-rimmed glasses that accentuated his political image as an angry prophet of impending doom, he denounced rising crime and “violence in our streets” to roars of approval from the convention. “Security from domestic violence, no less than from foreign aggression, is the most elementary and fundamental purpose of any government,” Goldwater intoned, “and a government that cannot fulfill that purpose is one that cannot long command the loyalty of its citizens.”3

The unexpected conjunction of these two events represented a pivotal juncture in the nation’s history, which had previously featured intermittent episodes of public interest in law enforcement and criminal justice. Although the federal government had periodically embarked on crusades against crime or immorality in the past, and plenty of local, state, and national politicians had voiced similar ideas, Goldwater’s words combined with impending developments would have an impact in the future that few of his listeners or viewers—not even devoted friends or avid foes—could have anticipated.4

On Saturday evening, thousands of Central Harlem residents took to the streets to protest the Powell shooting and other grievances. Most were bystanders, not participants, in the violence that erupted during the next three nights. The unrest then spread to Bedford-Stuyvesant (Bed-Stuy), a section of Brooklyn, for another three nights. In both communities, the rioting and looting were intense, although the vast majority of black residents, regardless of their sympathies or beliefs, never ventured from their homes or apartments.5

The Harlem Riot, as most whites called it, was accompanied by hundreds of injuries and arrests as well as at least one death. In both neighborhoods, the business districts were devastated, with white-owned and black-owned stores vandalized and ransacked. Soon the rebellion or uprising, as some blacks described it, spread to other cities such as Rochester, New York, and sent shockwaves across the country.6 The first “long, hot summer” of the decade had arrived—and with it a new racial dynamic that would drive a wedge between the civil rights movement and many white liberals who had supported it in the early 1960s. The image of the black rioter now joined the symbol of the black criminal, which had deep roots in American history; together, they served as both the real and imagined basis of white anxiety.7

MAP 1. Central Harlem

MAP 2. Bedford-Stuyvesant

Goldwater had predicted the outbreak of civil disorder and blamed it on the doctrine of civil disobedience preached and practiced by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his followers. The Republican nominee also successfully conflated the disparate threats of crime and riots as he borrowed the issue of law and order from Democrats in Dixie, modified it, and propelled “domestic violence” from the margins to the mainstream of presidential politics. For decades southern whites had opposed civil rights in part by claiming that integration would lead to a sharp increase in racial crime and unrest, which conservatives attributed to black immorality. Now growing numbers of northern whites—even those in favor of racial equality—likewise feared that integration would harm public safety.8

The conservative appeal to law and order posed a serious threat to the liberal dreams of President Lyndon Johnson, who responded to the political pressure with a dual strategy. As the campaign for the White House reached a climax in the fall of 1964, he promised with extravagant rhetoric that the War on Poverty would combat the social conditions—rising unemployment, failing schools, and poor housing—that plagued urban ghettos and generated racial violence. With broad and bipartisan support from both liberals and conservatives, the president in the spring of 1965 also declared a War on Crime in the optimistic belief that it would raise the level of police professionalism and lessen the incidence or perception of police brutality—another source of black anger and frustration.

Johnson hoped and thought that better policing combined with social programs and a national commitment to civil rights would reduce black crime and unrest, which liberals attributed to white racism. But the War on Crime had limited impact, although it substantially widened the door to federal intervention in local policing. Within three years it had evolved into an anti-riot program in the wake of the unrest that Harlem had foretold—Watts in 1965, Newark and Detroit in 1967, Washington and more than a hundred other cities after the assassination of King in 1968. By then Johnson had decided not to run for another term and the War on Poverty was also in retreat, denounced and defunded by white conservatives who contended that it had encouraged and rewarded black rioters.9

After Republican President Richard Nixon moved into the White House, he recast the War on Crime as a War on Drugs, with the addict and dealer now joining the criminal and rioter as public enemies. Building on the political consensus in favor of a larger federal role in law enforcement and appealing to the public demand for law and order, Nixon in the 1970s targeted heroin as a major threat to American society, especially to middle-class suburbs where white youths were portrayed as the innocent victims of the drug trade. As cocaine became a growing menace, Republican President Ronald Reagan escalated the War on Drugs in the 1980s and Democratic President Bill Clinton expanded it even more in the 1990s. During these decades, conservatives and liberals in Congress, white and black, were consistently supportive.10

The bipartisan War on Drugs has cost tens of billions of dollars to date. It has also harmed minority families and communities across the nation. In 2014, fifty years after the Harlem Riot, the United States had more prisoners behind bars by a wide margin than any other country in the world—most of them poor young men of color convicted of nonviolent crimes. And it had a rate of incarceration between five and ten times as high as in Western Europe and other democracies. Although on the decline, the rate remained historically high in comparison to incarceration levels in the United States from the mid-1920s to the early 1970s.11

In recent years, public attention has also focused on the militarization of policing—a collective legacy of the 1960s riots—and the deaths of unarmed blacks at the hands of armed whites. Sometimes they result from civilian actions—as when Trayvon Martin was shot in Florida by a neighborhood watch volunteer in 2012. Often the killings are a consequence of police actions, justified or not, which have caused sadness and anger in black communities across the nation. And on occasion they have led to renewed outbursts of civil unrest, as in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 and Baltimore, Maryland, in 2015.12

Today James Powell is forgotten by politicians, policymakers, and even participants in the Black Lives Matter movement. But his death was a catalyst for the Harlem Riot, which holds historical significance because it foreshadowed the disorders of the decade and helped set the stage for the politics of crime and policing, which has affected the lives of millions of minorities for more than half a century.

No one to date has written an in-depth history of the racial unrest in New York City in July 1964.13 This day-to-day, street-level narrative is intended to recapture that story and, in the process, provide some historical background for our current predicament. It is important to understand how the riots in Harlem and Brooklyn, although not the direct cause of the prison crisis, influenced the political context in which the crime and drug policies of recent decades have unfolded. In the Heat of the Summer—the title comes from a song by the folk artist Phil Ochs—shines a spotlight on the extraordinary drama of a single week when peaceful protests and violent unrest intersected, law and order moved to the forefront of presidential politics, the freedom struggle reached a crossroads, and the War on Crime was set in motion.

Why no complete account of this critical moment exists is a mystery. The Harlem Riot typically gets only a couple of paragraphs or pages in the standard versions of urban unrest. Even the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (better known as the Kerner Commission) largely ignored it. Although New York was not the worst riot, it was the first major civil disorder of the 1960s. It also erupted in the media capital of the United States and presaged unrest to come. Yet a comparative silence surrounds the clashes in Central Harlem and Bed-Stuy—an odd oversight given the way the national media have commemorated the racial fires that transformed other cities.14

Watts, Detroit, and Washington have all generated important books. Even a smaller city like Rochester—which had a riot the weekend after Harlem—has become the subject of July ’64, an award-winning documentary film. Perhaps the violent events in New York, which attracted national and international coverage at the time, failed to fit the conventional narrative, which presents 1964 as a year of tragedy and suffering—symbolized by the disappearance and murder of three civil rights workers in the South—that led to triumph and redemption in the form of the Civil Rights Act. Possibly the unrest in Harlem and Brooklyn was simply overshadowed by the far deadlier and more destructive disorders that began in 1965. In the end, it is hard to know exactly why the largest riot of “Freedom Summer” has not received the attention it merits.15

To correct this omission and tell the story as accurately as possible, I have supplemented new discoveries from historical archives with personal interviews I conducted with dozens of Harlem residents, police officers, political activists, city officials, and print journalists, black and white. Few of my interviewees had ever spoken for the record of their experiences in July 1964. For many it was difficult, even painful, to reconstruct the past. Yet their memories and observations provided me with insights that I could not have gained elsewhere.

Nevertheless, it is impossible to reconstruct with certainty what happened in Central Harlem and Bed-Stuy more than fifty years ago. Even then the events were hazy; now they are shrouded by time. This account instead concentrates on the human dimension of the urban unrest by incorporating a broad range of personal perspectives—black and white, young and old, Christian and Jewish, angry and fearful as well as radical, liberal, and conservative. On almost every page, it showcases the voices of demonstrators and police, officials and reporters, merchants and looters, community activists and ordinary citizens. In providing these diverse and divergent perspectives, my aim is to present the viewpoints of those who were involved as fully and fairly as possible without making assumptions or passing judgments unless the evidence warrants it.

Some of the figures in this book are readily recognizable, such as Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (no relation to James Powell), and Governor Nelson Rockefeller; black leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, and Malcolm X; black scholars or artists like Kenneth Clark, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, and Ralph Ellison; and white journalists like Jimmy Breslin of the Herald Tribune and Gay Talese of the New York Times. Others are undeservedly obscure, such as George Schuyler, a conservative black commentator who served on the grand jury that reviewed the Powell shooting; Earl Caldwell, a black reporter who was launching his career; and Lloyd Sealy, the first black police officer to assume command of the 28th Precinct in Central Harlem and then reach the rank of assistant chief inspector.

The narrative, which moves back and forth from the streets of New York to the corridors of the White House, has two central characters: Lyndon Johnson and Bayard Rustin. It is difficult to imagine two more different people in the summer of 1964: Johnson, the coarse and ambitious Texan politician who was determined to win the presidential election so that he could extend civil rights, build a Great Society, and surpass the historic achievements of his political hero, Franklin Roosevelt; and Rustin, the sophisticated civil rights activist, pacifist, and socialist who after decades of nonviolent struggle against racial segregation was eager to seize the opportunity to advance his dreams of racial equality and economic justice.

Even so, Rustin and Johnson were united by their shared goals and common vision of the Harlem Riot as a major threat to their political ambitions. The racial unrest, they worried, might discredit the cause of civil rights; it might even lead to the election of Barry Goldwater by alienating white liberals and moderates who were sympathetic to the freedom movement but afraid of what the urban protests might portend. And so both the activist and the president worked feverishly, with limited success and unforeseen consequences, to stop the rioting and looting before it could spread.

Night after night, Rustin walked the streets of New York promoting nonviolence and risking his personal safety to pacify the angry youths who had lost patience. Day after day, Johnson worked the phones and levers of power in Washington in an effort to find the right political balance between firmness and compassion, law enforcement and social programs aimed at restoring hope to those who were hurling rocks and debris. Ultimately, the crisis made them allies or partners of a sort and led to greater respect between them—but it also left them vulnerable to criticism from both radicals and conservatives, which prefigured the fate of liberals later in the decade.

A final note of my own: I was born in New York in April 1964. At the time my parents were living on King Street in the West Village. In researching this project, I found a letter in the Municipal Archives that my father, a Brooklyn native, had written to the deputy mayor in charge of police brutality on July 27, three days after the final clashes in Bed-Stuy had subsided. In the letter, which was subsequently forwarded to NYPD Commissioner Michael Murphy, my father contended that the “tension and mistrust” between the police and the public was due in part to a mutual lack of respect or courtesy. A middle-class Jewish American, he observed that uniformed patrolmen, who were typically working-class Irish or Italian Americans, routinely addressed him as “Johnny” or “Mac” (not “Mister”) and my mother as “sister” or “girl” (not “Miss”).16

“Presumably the citizen is supposed to bite his tongue and accept this for the sake of law and order,” my father wrote. But he wondered whether officers “insensible to an individual’s dignity” were not also “insensible to the individual’s rights.” If police disrespect was mainly a result of “bad training,” as my father hoped, then perhaps better instruction or stricter discipline could make basic courtesy as important to officers as keeping their “shoes shined and uniform pressed,” although he conceded that preventing police brutality was a higher priority, especially for minority residents. In response, he received a two-sentence form letter. But today police cars in New York have three words—whether observed more often in the breach or not—emblazoned on the side: Courtesy. Professionalism. Respect.17

Discovering my father’s letter—which he had long forgotten—was not only an unexpected connection to family history. It was also a priceless reminder that respect for the dignity of all should matter to all. As a wise and generous friend once told me, the most valuable gift a historian can possess is empathy for the people about whom he or she writes. I hope this book meets that standard.