Читать книгу In the Heat of the Summer - Michael W. Flamm - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

THE GATHERING STORM

Down the street they were rumbling

All the tempers were ragin’

Oh, where, oh, where are the white silver tongues

Who forgot to listen to the warnings?

—Phil Ochs, “In the Heat of the Summer”

FRIDAY, JULY 17

The morning after James Powell’s death at the hands of Thomas Gilligan, fifty officers arrived at Wagner Junior High School, site of the confrontation. The patrolmen were armed with nightsticks, not standard equipment for a daytime assignment. Consultations immediately began between the NYPD, school principal Max Francke, and Madison S. Jones, executive director of the City Commission on Civil Rights, who had offered his services to Francke in the wake of the shooting and protests on Thursday. After the police received assurances that only students would participate in the demonstration planned by CORE for later that morning, the nightsticks were returned to the 19th Precinct on East 67th Street. The officers, however, remained in place, hoping for the best but prepared for the worst.1

By 8 A.M. around seventy-five demonstrators had arrived, many with their school textbooks. Led by Chris Sprowal, the tall and slender chairman of Downtown CORE, they chanted “Police Brutality Must Go” and “Freedom Now.” They waved placards that proclaimed “Save Us from Our Protectors” and “Stop Killer Cops.” And they sang civil rights freedom songs such as “We Shall Overcome.” The protests were peaceful and organized in contrast to Thursday’s demonstrations. “We all know there are agitators around who profess violence,” said Sprowal. “We saw who they were and we weeded them out.” The pickets also were integrated. Most of the demonstrators were black, but several were white or Puerto Rican—one sign read “Demandamos El Fin De Brutalidad Policia.”2

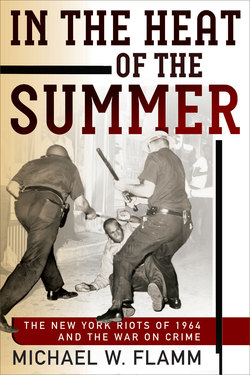

FIGURE 3. Police observe as demonstrators on East 67th Street protest the killing of James Powell. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection (LC-U9-12259 frame 1).

At noon the ranks of the demonstrators swelled with the addition of a hundred or so summer school students who had finished their morning classes. “People around here just want you to get into trouble,” warned Sprowal through a bullhorn as they prepared to march to the 19th Precinct. “Act like the young ladies and gentlemen that you are. Don’t act like they expect you to act. Hold your heads up.” Because the station house was on the same block as a firehouse, the Russian Mission to the United Nations, and the Kennedy Child Study Center, only a token group of twenty-five demonstrators was permitted to picket in front. The remainder paraded a block away next to the Lexington School for the Deaf, whose students came outside to observe and discuss the protest in sign language. An hour later, the demonstration ended and Sprowal urged the students to return daily until the date of the funeral was set.3

As the students began to disperse, three members of the Organization of Afro-American Unity arrived. Followers of Malcolm X, who had formed the group after he split with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, they counseled the teens not “to let people push you around.” But their leader was not in New York at the time—he was in Cairo attending a meeting of the Organization of African Unity. In his capacity as an observer, Malcolm X issued a statement that linked the struggles in America and Africa. “Our problem is your problem,” he informed the delegates. “It is not a Negro problem, nor an American problem. This is a world problem, a problem for humanity. It is not a problem of civil rights, it is a problem of human rights.”4

Segregation and discrimination in the United States, Malcolm X added, were worse than apartheid in South Africa because white Americans hypocritically preached integration and equality. “Out of frustration and hopelessness our young people have reached the point of no return,” he wrote. “We no longer endorse patience and turning the other cheek. We assert the right of self-defense by whatever means necessary, and reserve the right of maximum retaliation against our racist oppressors, no matter what the odds against us are.”5

The implied threat triggered an immediate reaction from Police Commissioner Michael J. Murphy. “Nobody will be allowed to turn New York City into a battleground,” he declared. Local activists like Malcolm X, he contended, had a “lust for power” and “other sinister motives.”6 Many blacks in Central Harlem would nevertheless heed the message in the coming days, although without the leadership and direction Malcolm X might have provided. His absence contributed to a vacuum that others would try, without success, to fill.

The Progressive Labor Party (PLP) also had representatives at the protest on East 67th Street that day. Formed by dissident members of the Communist Party in 1961, the group believed that both the Soviet Union and American leaders had betrayed the revolution by advocating reformist positions such as “peaceful coexistence” with the noncommunist world. The PLP was dedicated to an immediate grassroots class struggle based on the Chinese Communist model of resistance. The most prominent black member was William Epton, chairman of the Harlem branch, who was later convicted of conspiring to riot and criminal anarchy in the aftermath of the violence that would erupt on Saturday night. But on Friday morning he too was not present. Instead, a teenager from Monroe, North Carolina, was representing the PLP and distributing leaflets. In his hometown, the youth said, “If the cops shoot a Negro, we arm ourselves and get that cop worse than he got us.” Such talk alarmed the CORE officials, who urged the students to remain peaceful and orderly.7

But as the demonstrators started to head home, a white passerby saw the “Stop Killer Cops” placard and yelled, “He [Powell] deserved killing.” The students made a rush for the man, but the police got to him first, hustled him behind their barricade, and told him to keep his mouth shut and leave. When asked by reporters to give his name the man refused to answer, but offered two rhetorical questions: “What the hell business do they have carrying knives? What was the cop supposed to do, stand there and get stuck?” Other white New Yorkers were likely having a similar reaction to the Thursday shooting because of a rash of crimes in the streets and on the subways.8

On Friday afternoon, two white men were assaulted and robbed in the Bronx by roving bands of black teens who were not part of the CORE demonstration. On a southbound train, an elderly actor named Julian Zalewski was attacked by a gang of youths, who threw him to the floor and took his wallet and watch. “I got my Polish up and began to fight,” he said. “I yelled in my best theatrical voice, so loudly that the whole gang took off.” But not before he was punched and kicked. Elsewhere, a white pharmacist from Yonkers was accosted on a downtown express by two dozen black teenagers, six of whom punched and kicked him while their friends watched. None of the fifteen other adult passengers in the car came to his assistance, which the victim found disappointing though understandable. He would, he admitted, have done the same. Neither incident was unusual—according to the Transit Authority, subway crime had increased 30 percent in the past year.9

In early 1964, the subways were not the only unsafe place in New York, where police neglect, corruption, and brutality as well as disrespect had caused tensions between black residents and white officers for decades. According to the NYPD, every category of violent crime experienced a double-digit surge between June 1963 and June 1964. Rapes and robberies soared by 28 and 26 percent, respectively. Assaults rose by 18 percent and murders—usually a statistic beyond dispute because of the presence of a body—increased by 17 percent. Not since 1953 had the crime rate swelled so dramatically across the board. It was not surprising, then, that fear and anxiety over violence in the streets had reached a crescendo by mid-July, especially since New York historically experienced more homicides in the summer, when temperatures climbed and tempers flared, than in any other season.10

Many liberals, black and white, refused to accept the statistics at face value. Some contended that they were the product of new data systems or the public’s growing willingness to report certain crimes, such as rape or burglary (for insurance purposes). Others argued that the police had a vested interest in either minimizing crime (to demonstrate effectiveness) or exaggerating it (to justify more funding). Even the FBI at times expressed doubts about the NYPD’s numbers. Selective enforcement (lax or strict) of certain laws could also affect the statistics, as could the biased actions of prosecutors, judges, and juries. Black leaders such as Congressman Powell regularly asserted that the disproportionately high arrest rate of African Americans was proof of police racism.

Beyond dispute were the racial tensions created by police neglect of minority neighborhoods, which was a long-standing issue. In the aftermath of the Harlem Riot of 1943, the Amsterdam News had insisted that the NYPD had a duty and an obligation to provide black residents with the same degree of protection as white citizens elsewhere in the city. “While unalterably opposed to police brutality, we are equally strong and all-out for police efficiency,” it editorialized. “[W]e cannot agree that the interest of Harlem or New York—its welfare, its health, its morals, its safety—is being served by allowing a criminal element, however small, to overrun any special community.”11

Twenty years later, however, many white officers remained leery of inciting trouble in black communities. David Durk was an unusual recruit, an Amherst graduate from the Upper West Side whose father had a medical practice on Park Avenue. After a year at Columbia Law School, he decided to join the NYPD in fall 1963 and was assigned to the 28th Precinct in Central Harlem. At roll call a veteran sergeant offered clear instructions to the rookie patrolman: “Don’t lose sight of your partner, don’t go down any block alone, don’t go into any buildings, and no arrests unless you’re personally assaulted.” In other words, be careful, avoid trouble, and leave the residents to fend for themselves.12

Not surprisingly, a survey conducted on the eve of the riot in 1964 revealed that although 51 percent of African Americans in New York credited the police with doing a “pretty good job,” 39 percent disagreed and an equal number named “crime and criminals” as the “biggest problem” facing the city. The fear cut across gender, class, and generational lines in the black community. “There’s just too many junkies and drunks around here,” said a teenage woman who lived in a rundown apartment on West 146th Street and had a scar on her arm from a slashing by a wino. “It’s hard for decent people to live right. I feel like I’m smothering.”13

Ten blocks north, in a cool and spacious apartment, a middle-aged city official offered his view from a comfortable sofa. “You don’t know how much it tears me up to say this,” he admitted, “but the most hellish problem Negroes up here have to worry about, next to bad schools and bad housing, is personal safety from muggers and thugs. I don’t let my wife go out, even to the grocery store, at night unless she is escorted or takes a cab.” In Queens, a subway motorman argued that blacks could not depend on the police. “The only solution to all this mugging and stealing is to organize block associations or civilian patrols,” he said, bemoaning police indifference. “It’s time we did something to protect our own.”14

Police corruption was another source of hostility between many residents of Harlem and the officers who patrolled it. A housewife interviewed in 1964 was blunt: “The real criminal in Harlem is the cops. They permit dope, numbers, whores, gangsters to operate here, and all the time they get money under the table—and I ain’t talkin’ about $2 neither.” A college-educated Brooklyn resident was equally direct: “A ghetto police force is a force in league with all of the underworld, a bribed force. If this is not so, why is it that anyone can buy narcotics, alcohol, women or homosexuals freely on Harlem’s streets—even on Sunday?”15 Other socially conservative African Americans held similar views.

Congressman Powell spoke for these residents when he gave a series of speeches on police corruption in 1960 on the floor of the U.S. House, where he had immunity from charges of libel or slander. In his remarks, he offered what a historian has described as a “phone directory of the Harlem underworld” and a detailed description of the regular police protection pad. With names and dates, facts and figures, the congressman outlined how the bribes were distributed in the NYPD chain of command. Noting that all 212 captains and 59 of 60 inspectors were white, Powell charged that organized crime and police graft were “pauperizing Harlem” by siphoning funds from poor blacks to white mobsters and officers.16

Few paid attention, with the important exception of the New York Post, which assigned a team of investigative reporters led by Ted Poston, who had moved from Kentucky to Harlem in the 1920s and become the first black journalist at a major white newspaper. He confirmed the substance of Powell’s allegations. But then the congressman appeared on local television, where he had no immunity, and named a black woman, Esther James, as a courier of money from gamblers to the police. She decided to sue him for libel. When Powell arrogantly chose not to attend his own trial, the jury reacted negatively and found him guilty. In 1963, the court imposed $211,500 in damages. He in turn refused to pay, which led to a self-imposed exile from Harlem for five years. Powell could visit only on Sundays because, by state law, no one could serve civil contempt warrants on that day. As a result, he was unable to play a major role in restoring peace in 1964, even after he returned to Washington from his latest European excursion.17

The full extent of police corruption became public knowledge in 1970, when the Knapp Commission held hearings and heard testimony from dozens of witnesses, many of whom vividly described decades of bribes and payoffs in Harlem. Inspector Paul Delise, a decorated twenty-seven-year veteran with six kids and retirement on the horizon, told how, as a mounted cop in Harlem in the 1950s, he had arrested a drug dealer outside a pool room on 116th Street. The dealer offered him a wad of cash. When a squad car arrived, he reported the bribe. The officers suggested he take it. “You son of a bitch. How can you suggest something like that?” replied Delise heatedly. “We’re all doing it,” the officer responded. “We kick these guys in the ass, we take their works from them, we put ’em on a subway train, and whatever they have in their pockets is what we take.”18

Other policemen offered similar accounts. Jim O’Neil recalled how in 1964 he and his partner always gave the duty officer a half share of the “hat”—a tradition where “illegal gamblers, wanting to show their gratitude, would walk up to a detective and stuff a twenty in his shirt pocket and say, ‘Why don’t you take this and buy yourself a hat?’” It was, according to O’Neil, “more of a thank you than a bribe.”19 But according to Robert Leuci, who joined the force in 1961 and also appeared before the Knapp Commission, a captain told him that Harlem alone contained forty numbers operations that paid $100 a day, 365 days a year, to remain open. “The money was major, the backbone and heart of corruption in New York City,” testified Leuci, who became a pariah in the department and was the subject of the film Prince of the City starring Treat Williams and directed by Sidney Lumet. “The pad went all the way up, right through police headquarters into the mayor’s office.”20

The verdict of the Knapp Commission was blunt: “We find corruption to be widespread.” The “nut” (the monthly share per officer) ranged from $400 in Midtown to $1,500 in Harlem, which was known as the “Gold Coast” because it offered so many opportunities for bribes and payoffs. The “meat-eaters” were those who actively sought them; the “grass-eaters” were those who passively accepted what came to them. “You can’t work numbers in Harlem unless you pay,” testified a runner. “You go to jail on a frame if you don’t pay.” Police corruption weakened “public faith in the law and police,” concluded the commission. “Youngsters raised in New York ghettos, where gambling abounds, regard the law as a joke when all their lives they have seen police officers coming and going from gambling establishments and taking payments from gamblers.”21

No joke to many blacks was the ever-present possibility of police brutality, a constant source of conflict in Harlem, where black citizens often viewed white officers with hatred and suspicion. James Baldwin perhaps put it best. “It was absolutely clear that the police would whip you and take you in as long as they could get away with it,” he wrote in The Fire Next Time. “They had the judges, the juries, the shotguns, the law—in a word, power. But it was a criminal power, to be feared but not respected, and to be outwitted in any way whatever.”22 Sometimes the police would not even bother with an arrest. According to the NAACP, which took an active role in investigating police brutality, forty-six unarmed blacks were shot and killed by officers in New York between 1947 and 1952—only two unarmed whites met similar fates.23

Two incidents in particular generated outrage. The first came in 1950, when two white officers shot and killed a black Korean War veteran discharged from the Army twelve hours earlier. John Derrick was in uniform and missing $3,000 in discharge pay when his body was identified on 119th Street at Eighth Avenue. “John never even had a gun,” a witness told a crowd of three thousand at a rally the next day. “He was murdered.” The Amsterdam News pledged that “while there is an ounce of ink in our presses, we will pursue this case until justice is done.” But Republican Mayor Vincent Impellitteri refused to express remorse, offer condolences, or take action until Congressman Powell demanded that the commissioner transfer the officers out of Harlem within twenty-four hours. “We don’t call them that,” said Powell angrily, “but we do have lynchings right here in the North. If a lynch mob can be investigated in Georgia, the murder of a Negro by two police officers in New York should be investigated.” It was, but both local and federal grand juries failed to indict.24

The second incident came in 1951, when white officers beat William Delany unconscious outside his home. A polio victim with severe disabilities, Delany was the nephew of Justice Hubert Delany, a political powerbroker who had served officially as the tax commissioner in the La Guardia administration and unofficially as the mayor’s liaison to the black community. The justice was enraged by the attack on his relative. The “police in Harlem consider that they have the God-given right … to keep the peace with the nightstick and blackjack whenever a Negro attempts to question their right to restrict the individual’s freedom of movement,” he said. “Police brutality has been the mode in Harlem for years. The nurses and staff at Harlem Hospital see the bloody results daily. No policeman in Harlem has been convicted for police brutality or murder in over thirty years of many unnecessary killings, and hundreds of cases of brutality.”25 And none were in the Delany case.

Police brutality was a major cause of racial tension in Central Harlem. But it is difficult to determine how widespread or prevalent it was. On the eve of the riot in 1964, the New York Times had conducted a survey of blacks from all walks of life and all over the city. More agreed that there was no police brutality (20 percent) than “a lot” (12 percent). More than half of those surveyed believed that it was not common or routine; 85 percent had never witnessed a single act of police brutality, compared to only 9 percent who said they had. For most African Americans the main problems were jobs and housing, followed by crime and education.26

At times some black police may have used excessive force on the job. Jim O’Neil joined the NYPD in June 1963. One night, his first alone on post, he was stationed at the corner of 129th Street and Lenox Avenue when he heard a commotion from a nearby bar. Before he could take action, three large black officers in uniform—“at least a thousand pounds of cop on the hoof”—had exited a 1959 Chevy and entered the establishment. O’Neil watched as one of the policemen moved behind the man who was screaming at the bartender, “balled his hand into an enormous fist, and brought it down on top of the guy’s head in a pile driver-like motion.” With the man on the floor unconscious, the officer walked out and said to O’Neil, “If you want him, kid, take him, he’s your collar.” But O’Neil was afraid to take credit for what seemed like police brutality. He told his sergeant, who laughed at him. “You were just introduced to the King Cole Trio,” he said. “There isn’t a person in Harlem who doesn’t know them. They’re famous up here and probably do more to keep the peace than all the other cops in the precinct combined.”27

For Baldwin, however, white officers were primarily responsible for police brutality. “[T]he only way to police a ghetto is to be oppressive,” he wrote of them. “Their very presence is an insult, and it would be, even if they spent their entire day feeding gumdrops to children. They represent the force of the white world, and that world’s criminal profit and ease, to keep the black man corralled up here, in his place.” In Harlem, the white policeman was simply hated. “There is no way for him not to know it: there are few things under heaven more unnerving than the silent, accumulating contempt and hatred of a people,” continued Baldwin. “He moves through Harlem, therefore, like an occupying soldier in a bitterly hostile country; which is precisely what, and where he is, and is the reason he walks in twos and threes.”28

But Police Commissioner Stephen Kennedy refused to station more black officers in Harlem, ironically because of liberal pressure. “It seems to me this would be turning back the clock and you would be segregated in the department,” he said in a decision applauded by major civil rights organizations, now opposed to what they saw as the ghettoization of black patrolmen. Kennedy added that “an integrationist believes that a policeman is a policeman, regardless of color.” Whether he truly believed in the wisdom of dispersing the department’s relatively few black officers—African Americans were 16 percent of the city’s population but only 5 percent of the police force in 1964—is impossible to know. But not until after the unrest in Harlem was a black captain—Lloyd Sealy—placed in command of the 28th Precinct.29

Sensing trouble, Commissioner Kennedy created a special unit to handle urban unrest in 1959. The Tactical Patrol Force (TPF) was an elite squad of physically imposing young men (all under thirty years old and most over six feet tall) with special training in the martial arts and unit tactics. It attracted officers with a taste for adventure and the rough side of urban policing. For O’Neil, the son of a city fireman, the path to the TPF was circuitous. After leaving high school and serving in the Navy, he worked in retail management for five years before a friend asked him to take the Police Department’s entrance exam with him. They made a bet to see who would get the higher score.30

O’Neil won the bet—and his reward was a spot in the academy, where a veteran sergeant informed the cadets that they had to become proficient in the use of their weapons. “Just remember once you pull the trigger only the hand of God can take that bullet back,” he warned. Then he offered what O’Neil described as “unofficial department policy”: “Never shoot to wound, always shoot to kill.” Before graduation in 1963, O’Neil applied for an assignment to the TPF. At his interview, he met the commanding officer, Inspector Michael J. Codd, who was tall and fit “with a full head of neatly combed gray hair and blue eyes that cut the air like sharpened steel.” Codd was courteous but curt, and O’Neil assumed that he had not made the cut. But then he got the word and was ecstatic. “I was going to be part of an elite, ass-kicking, crime-fighting, gut-busting squad,” he recalled in his memoir A Cop’s Tale, “and I couldn’t wait to get started.”31

Robert Leuci joined the TPF in 1962 after calling every day for weeks in search of an opening, despite the fact that he was only five feet nine inches tall. What excited him was the work and that most of the men in the unit were “ex-marines and paratroopers, all with an appetite for the things that active street cops enjoyed, the jobs that most other cops avoided as a matter of course.” He was from a poor family in Bensonhurst, an Italian section of Brooklyn, and his brother had died of a drug overdose, which was probably why narcotics graft continued to trouble Leuci long after many other police officers ceased to see it as “dirty money.” His father was a union organizer who read four newspapers a day and was a staunch liberal (it was only during the Red Scare of the 1950s that he had stopped reading the Daily Worker and dropped his membership in the Socialist Party). At first he opposed his son’s choice of career, but during the social change and racial turmoil of the 1960s he came to support it. “Just be a good cop, don’t be a schmuck, treat working people fairly,” he counseled.32

Leuci tried his best to follow the advice, but it was difficult. On his first night with the TPF, he recalled assembling on a street corner and receiving the hostility of the neighborhood. “We thought we were there to help,” he wrote in his memoir All the Centurions, “but they saw it as an invasion of their neighborhood. Back then I didn’t understand the rage I saw in their faces, the contempt.” Aggressive policing was the only kind practiced in the TPF, and in the ghetto that created anger and antagonism. “They didn’t like us, simple as that,” he remembered. “They felt we were intruding in their lives. And we were. TPF didn’t only patrol the streets—we went into the alleyways, the basements, onto the rooftops, through the tenement hallways.”33 But for Leuci the job provided an adrenaline rush like no other, even if the price was alienation from the community.

By 1964 the corrosive combination of police neglect, corruption, and brutality had led many blacks in Central Harlem to question and challenge, directly or indirectly, the authority and legitimacy of the NYPD. But of perhaps equal or even greater importance, although less publicized, were the daily discourtesies inflicted upon many residents by white officers. It was the “small indignities”—the constant rudeness and casual racism—that most offended Percy Sutton, a prominent lawyer and future borough president. He wondered why the Police Academy could not devote more time to training cadets in basic civility. Police harassment of black residents was, admitted then-Lieutenant Anthony Bouza, who visited 125th Street regularly, “a form of Chinese water torture” that led to a flood of resentment and anger.34

At the same time, the growing violence and disorder in New York posed a classic case of cognitive dissonance for many whites. Intellectually, they knew that most blacks were not muggers; emotionally, they could not ignore the sense that most muggers seemed black. Adding to the racial tension and providing human faces to the grim statistics were a dramatic series of high-profile events and a disturbing number of sensational black-on-white crimes in the first six months of the year.

Even before the Harlem Riot, Bayard Rustin was a well-known figure in New York. In mid-January, on the heels of the March on Washington, he received an urgent call from Milton Galamison, a Brooklyn minister. He wanted to know whether Rustin was willing to dedicate his organizing talents to a citywide boycott designed to protest the rampant segregation and glaring inequities in the school system. More than 40 percent of the students were minorities; fewer than 3 percent of the teachers were black. A decade after the Brown decision, spending on white students was seven times higher than on nonwhite students. Despite reservations about the mercurial Galamison and the shaky coalition of parents and activists behind the boycott, Rustin agreed. But he had only two weeks to work his magic. No matter—with extraordinary energy and unrelenting attention to detail he largely succeeded.35

At Siloam Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, Rustin established a “war room” staffed around the clock with volunteers. At age fifty-three, he still had the energy of a much younger man, routinely putting in eighteen-hour days and at times sleeping at the church in pajamas, a bathrobe, and slippers rather than returning to his Manhattan apartment on 28th Street and Eighth Avenue. “Do not think,” he told others in reference to the white in his hair, “that just because there is snow on the roof there is no fire in the furnace.” To keep the fire stoked, he subsisted on cold coffee and cheese sandwiches while making endless lists and taking copious notes on yellow legal pads. The holes in his shoes were a testament to his dedication and a reflection of his pay—around $71 a week for a labor of love and principle.36

On a cold and blustery Monday in early February arguably the largest civil rights demonstration in history took place. More than 450,000 mostly African American students (45 percent of total enrollment) boycotted classes in an effort to promote school integration. An estimated hundred thousand students attended almost five hundred freedom schools staffed by supporters of the protest. The president of the Board of Education was dismissive, but Rustin was publicly elated by the turnout (more than three times the normal absentee figure) and predicted that “we are on the threshold of a new political movement.” In a prescient moment, he also cautioned that the “winds of change are about to sweep over our city” and that those “who stand aloof from the frustrations and deprivations of the ghetto” could expect more unrest in the near future.37

The next day an exhausted Rustin canceled a speaking engagement at Syracuse University and agreed to meet with peace activists from Eastern Europe at the Soviet consulate. When he arrived he was greeted by photographers and reporters from the Journal-American and the Daily News, both conservative tabloids. “Boycott Chief Soviets’ Guest” blared the headline on Wednesday in the Daily News, which blasted Rustin for “consorting with the Soviets.” The presence of the press was not coincidental. The FBI, which back in November had tapped Rustin’s phone and planted a bug in his apartment (with Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s approval), had alerted the newspapers to discredit Rustin and the movement.38

In public, Rustin stood his ground, calling the controversy a “red smear.” But the damage was done and he knew it. In private, he told a friend that visiting the Soviet consulate was “a mistake.” The incident again made him persona non grata, at least officially, to moderate black leaders like Roy Wilkins and King, who now distanced themselves from him. After his long and arduous return from exile and isolation, Rustin was once more back on the outside.39

As the publicity surrounding Rustin subsided in March, white fears of racial violence resurfaced with news of the brutal murder and rape of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese, a twenty-eight-year-old Italian American bar manager. She lived in the Kew Gardens section of Queens in an apartment that she shared with her lesbian partner Mary Ann Zielonko. On the ground floor was the Interlude Coffee House, where folksinger Phil Ochs, who later wrote a song about the murder called “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends,” performed from time to time between bigger gigs. As Genovese was returning home from work in the early morning, she was attacked by Winston Moseley, a twenty-nine-year-old African American who later confessed to killing two other women and committing at least thirty burglaries. Genovese saw Moseley approach as she walked from her car to the building. She tried to run, but he caught her and knifed her in the back twice. “Oh my God, he stabbed me!” she screamed. “Help me!”40

A few of her neighbors heard her, but it was a cold night and, with the windows closed, they were not sure what she had said. When one man shouted, “Leave that girl alone!” Moseley fled and Genovese staggered toward the building, seriously injured. She was alive, but not visible to the residents and unable to enter because of a locked doorway. Ten minutes later, Moseley returned and found Genovese, who was still conscious. Despite her efforts at self-defense, he stabbed her several more times, stole $49, and raped her while she lay dying. Media accounts subsequently claimed, dramatically but inaccurately, that thirty-eight of her neighbors had heard her cries for help and failed to respond, which spurred psychological research into the “bystander effect” and led to an overhaul of the NYPD’s telephone reporting system.41

Ten days after the murder of Genovese, the police commissioner met Abe Rosenthal, metro editor of the New York Times, for lunch at Emil’s, a popular restaurant close to City Hall. Murphy, a large man with grim blue eyes, took his usual position (back to the wall) and ordered his usual meal (shrimp curry with rice). Three years into his tenure, he still resembled, in Rosenthal’s description, “a tough Irish cop because he is a tough Irish cop.” But unlike many of his fellow officers, Murphy was not born into the job. A native of Queens, he spent six years after high school with the Equitable Life Insurance Company. The work was monotonous, however, so he responded to an ad to become a state trooper. From the start he loved it. “One day I was solving a homicide,” he said, “and the next day I was on a motorcycle chasing speeders.”42

But after Murphy was married he joined the NYPD in 1940 so that he would not have to worry about a transfer out of the city. After five years he made sergeant—the fastest rise in the history of the department. At age thirty-two he was the youngest sergeant on the force; within nine years he was promoted to deputy inspector and put in charge of the Police Academy, where he instituted the equivalent of a college curriculum. A dedicated student, Murphy earned three degrees while working full-time. “He had a great legal mind,” said the dean of Brooklyn Law School, where Murphy graduated summa cum laude and first in his class in 1945. “You rarely get a student with the combination of alertness, pleasant personality, curiosity, and the power of analysis that this man had.”43

After the Academy Award–winning film On the Waterfront depicted brutal racketeering among dock workers, Murphy took a leave from the NYPD in 1955 to become executive director of the New York–New Jersey Waterfront Commission. Four years later, he returned to the department as chief inspector. In 1961, he became police commissioner, succeeding Stephen Kennedy. By then he was above all an administrator, but he remained an officer at heart. “Police work is the most fascinating in the world,” he said. “I don’t know of any other occupation that can approach it for variety and challenge.”44

On the day Murphy dined with Rosenthal at Emil’s, the challenge that most worried the commissioner was not the Genovese killing. “In the spring of 1964,” the Times editor wrote in Thirty-Eight Witnesses, his account of the case, “what was usually on the mind of the Police Commissioner of New York was the haunting fear that someday blood would flow in the streets because of the tensions of the civil rights movement.” Murphy was supportive of activists—to a degree. “If New York had a whole system of laws I considered unjust, I’d probably be out there breaking them,” he said. “But we don’t have those kind of laws here.” Nevertheless, he defended the actions of protesters—within limits. “I think they have a right to demonstrate,” the commissioner said, “and I’m prepared to protect and assist them so they can have their say with a minimum of interference to other men and women in the community.”45

Later in March, art imitated life—with a surprising and deadly twist—when a one-act play by LeRoi Jones (who had not yet changed his name to Amiri Baraka) premiered at the Cherry Lane Theater. Dutchman was a short but brutal play about Lula, a thirty-year-old white temptress in a tight dress, and Clay, a twenty-year-old black professional in a three-piece suit. They meet on the subway, where Lula first tries to seduce Clay. Then she challenges his authenticity and manhood as the dialogue crackles with insults and innuendo. Finally, Lula provokes Clay into slapping her twice and threatening to cut off her breasts.46

“Shit, you don’t have any sense, Lula, nor feelings either,” Clay explodes. “I could murder you now. Such a tiny ugly throat. I could squeeze it flat, and, watch you turn blue, on a humble. For dull kicks. And all these weak-faced ofays squatting around here, staring over their papers at me. Murder them too. Even if they expected it. That man there … as skinny and middle-classed as I am, I could rip that paper out of his hand and just as easily rip out his throat.” Clay finishes and prepares to leave the train. But Lula grabs a knife and stabs him twice. She and the other passengers quickly remove his body from the car. And when another young black professional enters and takes a seat behind her, she turns and gives him a long, slow stare.47

Dutchman was an immediate sensation and turned the twenty-one-year-old Jones into an instant celebrity. A year later, radicalized by the assassination of Malcolm X, he divorced his Jewish wife, moved from Greenwich Village to Harlem, changed his name to Amiri Baraka (or “blessed prince”), and became a founder of the Black Arts Movement. Baraka was later elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and named the poet laureate of New Jersey. But Dutchman was his first success, perhaps because it truly captured the tensions of 1964. “If this is the way the Negroes really feel about the white world around them, there’s more rancor buried in the breasts of colored conformists than anyone can imagine,” wrote the New York Times reviewer after opening night. “If this is the way even one Negro feels, there is ample cause for guilt as well as alarm, and for a hastening of change.”48

By the spring even moderates like Kenneth Clark were losing patience. The city’s failure to implement a comprehensive plan for school integration and Congress’s refusal to pass the civil rights bill rankled. “I must confess that I now see white American liberalism primarily in terms of the adjective ‘white,”’ he wrote in Commentary. “And I think [that] one of the important things Negro Americans will have to learn is how they can deal with a curious and insidious adversary—much more insidious than the out-and-out bigot.” Increasingly, Clark saw liberalism as an ideology of words rather than deeds, which “attempts to impose guilt upon the Negro when he has to face the hypocrisy of the liberal.”49 The fragile alliance of whites and blacks in the freedom struggle was fraying as disappointments multiplied and strains deepened.

More tensions flared in early April. With the World’s Fair set to open in several weeks, the Brooklyn and Bronx chapters of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) announced that they would conduct a massive stall-in unless the city immediately addressed the problems of police brutality, substandard housing, and failing schools. On the roads, bridges, and tunnels leading to Queens, black motorists would deliberately run out of fuel, pretend to have car trouble, or simply abandon their vehicles to block traffic. “Our objective is to have our own civil rights exhibit at the World’s Fair,” declared Oliver Leeds of Brooklyn CORE. “We do not see why white people should enjoy themselves when Negroes are suffering.” The plan generated an instant and negative response from James Farmer, executive director of CORE, who called it a “hare-brained idea” and suspended Leeds’s chapter. Similar reaction from city officials, daily newspapers, ordinary citizens, and liberal officials in Washington was equal parts outrage at the possible disruption and fear that the protest might damage public support for civil rights.50

Most mainstream civil rights leaders agreed with Farmer that the stallin was a tactical mistake. King and others found it difficult, however, to condemn the activists for proposing nonviolent civil disobedience. “Which is worse, a ‘Stall-In’ at the World’s Fair or a ‘Stall-In’ in the U.S. Senate?” King asked in reference to the filibuster against the civil rights bill. “The former merely ties up the traffic of a single city. But the latter seeks to tie up the traffic of history, and endanger the psychological lives of twenty million people.”51

Aware that he was losing control of CORE, Farmer stated that he would lead a protest at the exhibit halls of southern states that supported segregation. Meanwhile, Mayor Robert Wagner, who called the stall-in a “gun to the heart of the city,” announced that he would have more than a thousand police officers on the road and in the air, supported by three command centers and dozens of tow trucks, to act if needed. In the end, they were not—only a dozen motorists were arrested. But significant protests unfolded at subway stations and the opening ceremony, where Lyndon Johnson gave one of his first public speeches since becoming president. Farmer was taken into custody with supporters after blocking the doorway to the New York City Pavilion.52

Back in Harlem, crime continued to create anxiety. On April 11, a young white social worker named Eileen Johnston, who had only recently moved to New York from Chicago, went to Count Basie’s Night Club with a black co-worker. A few steps from the front door, two black youths confronted them. “This one’s mine,” said one of the assailants as he jammed a knife into Johnston’s back. Six days later, seventy-five teens overturned a fruit stand on Lenox Avenue near 128th Street and began to throw apples, oranges, and melons at each other. When four patrolmen arrived on the scene, they were greeted with a barrage of fruit and rocks. After twenty-five more officers responded to calls for assistance with pistols drawn and nightsticks swinging, the melee ended with five arrests and charges of police brutality at the station house where the suspects were taken. On April 29, a black teen stabbed to death a middle-aged Hungarian immigrant whose husband was critically injured when he tried to come to her aid in the used clothing store they operated.53

The crimes generated headlines in the mainstream media because they crossed racial boundaries. But in reality most acts of violence were either white-on-white or black-on-black, with African Americans disproportionately represented as both victim and perpetrator. That, however, was not news. “If a reporter phoned in what he believed was an interesting robbery or homicide in which the victim happened to be black, the editor invariably muttered, ‘Forget it,’” recalled Arthur Gelb, deputy metro editor of the New York Times. “Reporters, of course, knew better than even to suggest stories about crimes involving blacks against blacks. That was copy more suited for the Harlem-based weekly, the Amsterdam News.”54

Violent crimes that featured white victims and black assailants attracted national attention—even on the floor of the U.S. Senate, where the debate over the civil rights bill was under way. In mid-April, Democratic Senator Olin Johnston of South Carolina, an opponent of the measure, repeated the common conservative claim that the black freedom struggle encouraged lawlessness. Southern states, Johnston asserted in defense of segregation, “do not have the high rates of crime and juvenile delinquency of those states which are hotbeds of agitators against so many American institutions.” Another foe of the bill, Democratic Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, later raised the grim specter of Kitty Genovese during a verbal confrontation with liberal Republican Jacob Javits of New York, a staunch advocate of civil rights. “I say that couldn’t happen in the South, demean it as you may,” Russell heatedly charged.55

Individually, the crimes caused concern among whites. Collectively, they generated panic when a recently hired black reporter for the New York Times, Junius Griffin, reported in May that a new Harlem gang known as the “Blood Brothers” had formed with the “avowed intention of attacking white people” without provocation as part of an initiation ritual. “Why shouldn’t I hate all white people?” a member told the reporter. According to Griffin, the gang numbered between two and four hundred, although exact figures were hard to find. Allegedly, it was responsible for the murder of Johnston as well as the melee at the fruit stand and other crimes. Based on information supposedly provided to the reporter by a researcher for Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU), who had conducted taped interviews with many of the members, they were trained in martial arts and taught how to construct homemade weapons.56

A leader interviewed by Griffin said that “the main reason the gang started was to protect ourselves in a group against police brutality. If they’re going to hit one of us, and we’re by ourselves, then there’s no protection.” The “Blood Brothers,” he claimed, received financial support from numbers runners and drug dealers in Harlem. The NAACP and CORE wanted to help and had staged the school demonstrations. “But who wants an education,” he asked, “when you are going to have your brains knocked out or see your brothers or cousins shot by policemen?”57

Griffin was only the fourth black reporter on the New York Times, which like every major daily in the city had few African American writers on staff, a practice that would start to change during the summer of 1964. George Streator, a Fisk graduate, was hired in 1945 but fired four years later when it was found that he had fabricated quotes. Layhmond Robinson, Jr. was a Syracuse graduate and U.S. Navy photographer in World War II who joined the paper in 1950 after he earned his degree from the Columbia School of Journalism. Theodore “Ted” Jones was raised in Harlem and worked for the Amsterdam News while attending City College. After graduation, he joined the New York Times as a copyboy, and in 1960 was promoted to reporter. He was “the paper’s authority on Harlem,” recalled Gelb in his memoir. “But there weren’t many stories about Harlem that the Times—or, for that matter, any other white newspaper—deemed newsworthy.”58 Griffin was hired to rectify the situation.

Like Robinson, Griffin got his start in journalism in the military after growing up in a coal town and attending the two-room Stonega School for the Colored in Virginia. “I was in the Marines. I wanted to be another Ernie Pyle,” he recalled. “I struck a bargain: I agreed to reenlist; after a year, I’d get a transfer to Tokyo and be assigned to Stars and Stripes.” In Korea, he became one of only two black correspondents working for the military paper. In 1962, Griffin was discharged and headed to New York, where he joined the Associated Press and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize as one of eight reporters who wrote the series “The Deepening Crisis” on the civil rights movement. Two years later, he joined the New York Times when Rosenthal decided that he “wanted me in Harlem; Abe thought I could bring more depth to the black coverage.”59

Whether Griffin added more depth remains a matter of controversy within journalism circles—Ted Poston of the New York Post later contended that police had peddled the story for weeks before Griffin jumped at it, in part because “Negro scare stories” were a time-honored tradition at the metropolitan newspapers. Five days after his front-page article on the “Blood Brothers” appeared, the NAACP challenged his account. In a statement, it demanded that the state attorney general “put an end to the slanderous lies being propagated concerning the Harlem Community by daily press exaggerations of the so-called blood brothers.” Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins added that “from my own information, reports on [the gang] are without foundation.” And the Reverend Dr. Donald Harrington of the Community Church of New York was equally scathing. “I believe that this is an irresponsible story patched up out of fear and malice and a few instances of violence,” he said. “Not only will it be used to justify police violence in Harlem, but it has already further alienated the great racial communities.”60

Although the NYPD affirmed the gang’s existence, other newspapers were quick to criticize the Griffin article. It was, wrote Gay Talese, a New York Times reporter in 1964, “an opportunity they never miss when they think The Times has overstepped its traditional caution.” Even some veteran reporters on the paper wondered, however, when other journalists were unable to make contact with any gang members. In the newsroom, some began to describe the “Blood Brothers” story as “Rosenthal’s Bay of Pigs,” a reference to John Kennedy’s disastrous decision to approve an invasion of Cuba by armed exiles in April 1961.61 Like the former president, both Gelb and Rosenthal were relatively inexperienced—they had assumed their editorial positions only in the fall of 1963. More important, both were unfamiliar with what was happening in Harlem.

Rosenthal, the son of a house painter from the Bronx, was familiar with poverty. But his specialty was foreign reporting—he had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1960 for his coverage of Eastern Europe. Gelb was equally unprepared. “We did not know how to cover the wants and dreams of black people,” he admitted. “Harlem—it was like a foreign country.” When he and Rosenthal questioned Griffin, the reporter always claimed that the gang had dispersed after the attention and notoriety it had received. Twenty years later, when Gelb again spoke to Griffin, who by then was working for Motown Records in Los Angeles, he still “insisted that every fact in his stories had been the truth. Even though at times I had harbored some doubts, overall I found Griffin’s sincerity convincing.” Gelb also pointed out in an interview that no one has ever proven that Griffin fabricated the article. But fifty years later, Talese had no doubts. “That story was a fake,” he declared.62

The “Blood Brothers” article had a lasting and insidious impact. “The press, the radio and television had been building a kind of horrified lynch mob in the rest of the city against Harlem,” wrote a radical white journalist in a book about the “Fruit Stand” incident in April 1964. “The phrase about the long hot summer coming on was taken as a direct threat against whites. Every act of casual rowdyism involving black people was reported as an atrocity story. The Negroes were beginning to be described as completely out of control, tearing up subways, molesting and raping white women. White neighborhood vigilantes organized into roving patrols stopped and questioned every black man straying out of his home block. New York sounded to the rest of the country like some frontier town helpless before the uncontrollable violence stalking its streets.”63

Regardless of whether the “Blood Brothers” were fictitious, the fear that crime was causing in New York was all too real. In May, the Hasidic community in Brooklyn formed a civilian patrol quickly dubbed the Maccabees after the fierce Jewish tribe whose resistance to the Greek occupation of Judea is celebrated every Hanukkah. On the Sabbath, the patrol was augmented by Christian volunteers, both black and white. The decision to create the Maccabees came after a gang of fifty black teenagers attacked a group of Hasidic children and a rabbi’s wife was the victim of an attempted rape. The hope was that, if nothing else, the patrol might prevent another Genovese tragedy. “Yet no sooner do you rush reinforcements to Crown Heights than the terror leaps out in another part of the city or moves along underground,” commented National Review, a conservative magazine, “and the knife may be at anyone’s throat.”64

Tensions between the Police Department and many liberal New Yorkers had also risen to dangerous levels. In mid-May, Councilman Theodore Weiss introduced a bill with the support of CORE and the NAACP to create a new civilian review board composed of individuals without ties to the NYPD. The existing review board, created in 1955, consisted of three deputy police commissioners. As a result, observed Arnold Fein, chairman of the New York Committee of Democratic Voters, it lacked credibility. “In much of the public mind,” he wrote to Mayor Wagner, “such a board is engaged in the business of self-investigation and self-justification.” This perception was especially dangerous given the unrest and distrust in the city. “In the current period of racial tension, picketing, and demonstrations,” Fein added, “it is almost inevitable that there will be misunderstandings and clashes involving police, with recurrent charges of police brutality.” Even if most charges were false, which he believed was the case, a truly independent review board was needed to “clear the air, increase respect for legitimate police operations, restrain the lawless cop, and restrain those who make unfounded charges.”65

FIGURE 4. The Maccabees, a Jewish anticrime organization, patrol the streets of Brooklyn. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection (LC-U9-12191 frame 24).

Although the proposed review board would have limited authority—it could only make recommendations to the mayor and police commissioner—it met with fierce and immediate resistance from Commissioner Murphy. “In my opinion,” he stated at a city council public hearing, “this entire push for a citizens’ board is a tragedy of errors compounded by half-truths, innuendos, myths, and misconceptions.” The allegations of police brutality were “maliciously inspired,” he charged, and came from “self-aggrandizing, self-appointed leaders” whose “blind assertions” are “aimed at destroying respect for law and order and are, in effect, calculated mass libel of the police.”66

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which represented the twenty-six thousand officers of the NYPD, was equally critical. In a letter to Mayor Wagner in May, President John Cassese called the new board a “deliberate slap in the face” to his rank and file, who were overwhelmingly committed to the fair and impartial enforcement of the law despite a few isolated and inevitable abuses of power. Moreover, the police already worked under careful and constant scrutiny from the existing board, the general public, and Commissioner Murphy, who “is tougher and more stringent than any group of civilians would dream of being.” Above all, the police labored in a city filled with watchful, if not hostile, eyes.67

“Nowhere is there greater awareness of, sensitivity to, and sympathy with, the cause of civil rights and civil liberties,” Cassese contended. “Nowhere are the courts more vigilant, the news media more pervasive and aggressive.” He also offered two predictions or warnings. The first was that civilian appointees to the new review board would no doubt be “members of pressure groups that cannot be impartial,” such as CORE. The second was that an independent board would “deal a devastating blow to police morale and lead policemen to ignore sensitive situations rather than take the chance of getting into trouble with a civilian board with a special axe to grind.”68 Civilian oversight would cause the police to handcuff themselves and a city on the brink of chaos would become even more dangerous.

In June, Commissioner Murphy attempted to reassure the public. “All of us together can turn the threat of a long, hot summer into a cool, calm, constructive period of progress,” he said at the seventh annual pre-summer conference of the Police Department and the Youth Board. Among the gangs discussed were the Tiny Tims, the Buccaneers, the Imperial Lords, and the Medallion Lords, with an estimated total of seven to eight hundred members. No new information about the supposed “Blood Brothers” was made available, although the NYPD continued to claim the gang existed. Murphy made no mention of subway crime, including the nine incidents reported since May 29 alone, but emphasized that he did not believe that “this city will explode into bloodshed in the coming months.”69

At a press conference, Whitney Young, Jr. also tried to calm the racial fear by providing some perspective and balance. The executive director of the Urban League emphasized that he had always deplored violence “whether inflicted by Negro youth in urban settings like Harlem or by those who dynamite Negro churches in Alabama.” But he observed that “crime of all sorts—murder, rape, robbery, burglary and assault—has been no stranger to Harlem. Its citizens have been victimized for years with amazing indifference on the part of the general public, which turned its eyes and thoughts elsewhere. The only new dimension to the current violence is that the frustrations of the ghetto are spilling out beyond its boundaries and directly affecting the public at large.”70

Young recited the facts for all to hear—if they were willing to listen. The crime rate in Harlem was significantly greater than in the rest of the city. The murder rate alone was six times higher. In the overwhelming majority of cases, which the white media almost always chose not to report, it was black-on-black, with African Americans both the victims and perpetrators. It was time, Young added, to eliminate racial identification in crime stories. Reporters should not assign false motives or promote racial bias. “Crime does not carry a racial label,” he asserted. “There has always been crime and rioting, particularly among the poor of all races and nations, and especially wherever full citizenship, liberty, and opportunity were denied.”71 It was a brave but ultimately futile effort to soothe the jangled nerves of white residents.

The subways in particular seemed to provide daily tales of terror even as Mayor Wagner ordered an extra shift for all city and transit police, who were also told to wear their uniforms to and from work as an added deterrent. On one train, reported Newsweek in mid-June, a group of four black teens threatened to cut off the head of a motorman; on another, a group of five black youths demanded $10 from a white teen and then stabbed him in the shoulder when he refused to pay. “They’re animals, vicious animals,” said a middle-aged white woman. “And they talk about civil rights.” But Rustin objected strongly to what he saw as a false equivalence. “When such acts of hooliganism are carried out by whites,” he noted, “it is then called ‘juvenile delinquency’ and not ‘Irish delinquency’ or ‘Italian delinquency.’”72

In Washington, President Lyndon Johnson and Attorney General Robert Kennedy met to discuss the summer’s likely hot spots. On the top of the agenda were New York and Mississippi, where CORE volunteers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, part of the “Freedom Summer” voter registration campaign, disappeared in June after police officers and Klan members had beaten, tortured, and murdered them. “It is clear,” warned special assistant Richard Goodwin, “that the one domestic issue which could cause real trouble for the party this year is civil rights…. The chance of violence is high.” Rising expectations and temperatures might lead to a “series of explosions” in the South and the North that could have “serious political repercussions” and might require federal action. “We might well treat this as if we were waging a war,” he advised.73

In New York, two new anticrime measures went into effect in July. The “No-Knock” law enabled officers who had obtained warrants to search private residences without first notifying the occupants. The “Stop-and-Frisk” law allowed the police to question individuals and gather evidence on the basis of “reasonable suspicion.” Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a liberal Republican who later championed harsh antidrug measures in the early 1970s, had signed both laws four months earlier despite protests from the New York Post and Amsterdam News, which contended that they would give a “green light” to the most “bigoted or sadistic” officers. The NAACP also argued that “aggressive preventive patrol”—a common practice in urban policing by the early 1960s—would lead to greater harassment of racial minorities.74

Aggressive policing certainly led to greater tensions in Central Harlem, where the battle to control the street corners escalated. A member of the “Blood Brothers” declared that the gang planned to protest the new laws by staging a “hit” on either a patrolman in the 32nd Precinct or an officer with the elite TPF, which had flooded the area in pairs since the wave of high-profile crimes in April. Even if the threat was a bluff or bravado, it put the police on edge and made them apprehensive.75

As the school year ended, the panic among whites was growing and spreading. On July 16, two weeks after President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act and the same day that Thomas Gilligan shot and killed James Powell, National Review reminded readers that over Memorial Day weekend, twenty black teens had vandalized an entire subway car, punching, kicking, and knifing the terrified passengers. It was not simply another incident of urban mayhem. “What is happening,” asserted the conservative magazine, “or is about to happen—let us face it—is race war.”76

Forty-eight hours later, the riot began. “Harlem’s history is made on Saturday night,” observed author Claude Brown, “because for some reason or another, Negroes just don’t mind dying on Saturday night.”77