Читать книгу How Starbucks Saved My Life - Michael Gill - Страница 6

MARCH

ОглавлениеI should not have been anywhere near the location of that transforming experience. But on that particular rainy day in March of last year, I could not resist the urge to go back in time.

Have you ever wanted—when life is too hard to bear—to return to the comfort of your childhood home? I had been the only son of adoring if often absent parents, and now I wanted to recapture some sense of the favored place I had once occupied in the universe. I found myself back on East Seventy-eighth Street, staring across at the four-story brownstone where I had grown up.

I had a sudden image of a crane hoisting a Steinway grand piano into the second-floor living room. My mother had decided I should learn to play the piano, and my father had thrown himself into the project. Nothing was too good for his only son, and he had rushed out and bought the biggest, most expensive model. After the purchase of the huge Steinway, the problem became how to get this magnificent instrument into our home, a hundred-year-old house with narrow, steep stairs.

My father had been up to the challenge. He hired a crane, and then had the men raise it up to the second floor, where, by opening the French windows, and turning the piano on its side, they could just make it fit. My father had been terribly proud of his accomplishment and my mother delighted. Of course, I had been secretly happy to be the reason for all this unusual activity.

Today, as I gazed at the stately building that had once been my home, I thought of how much all of that extravagant effort must have cost. How far I had fallen from those happy times. I had come a long way from my childhood, when money was never mentioned. I was now nearly broke.

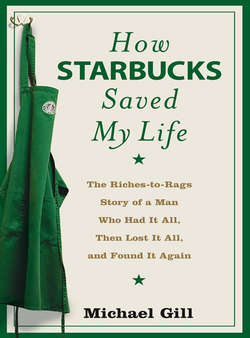

Turning away from the comforts of the past, I looked for some comfort in a latte. One of my last remaining treats. A Starbucks store now occupied the corner of Lexington and Seventy-eighth, where during my childhood there had been a pastry shop. In my depressed daze, I did not notice the sign in front reading: “Hiring Open House”—not that it was the kind of sign that I would have noticed anyway. Later, I was to learn that Starbucks has hiring events at different stores every week or so in New York. Managers from other stores in the area come in to interview prospective employees. Looking back now, I realize that the good fortune that had left my life returned the moment I chose to step into the store at the corner of Seventy-eighth Street.

Still in my own cocoon of self-pity and nostalgia about lost fortune and family, I ordered my latte and made my way over to a small table. I sat down and did not look at anyone nearby. Staring into my interior space, I tried to make sense of a life that seemed to have completely gotten away from me.

“Would you like a job?”

I was startled out of my reverie. The speaker sat at the table right next to mine, shuffling some papers with professional dispatch. She was an attractive young African-American woman wearing a Starbucks uniform. I had not even looked at her before, but now I noticed she was wearing a silver bracelet and a fancy watch. She seemed so secure and confident.

I was struck numb. I wasn’t used to interacting with anyone in Starbucks. For the last few months I had been frequenting many Starbucks stores around in the city, not as places to relax or chat, but as “offices” where I could call prospective clients—although none were now answering my calls. My little consulting company was rapidly going downhill. Marketing and advertising is a young man’s business, and at sixty-three, I had found that my efforts were met with a deafening silence.

“A job,” the woman repeated again, smiling, as if I hadn’t heard her. “Would you like one?”

Was I that transparent? Despite my pin-striped Brooks Brothers suit and Master of the Universe manner—I had my cell phone resting on top of my expensive leather T. Anthony briefcase as if expecting an important call—could she see that I was really one of life’s losers? Did I, a former creative director of J. Walter Thompson Company, the largest advertising agency in the world, want a job at Starbucks?!

For one of the few times in my life, I could not think of a polite lie or any answer but the truth.

“Yes,” I said without thinking, “I would like a job.”

I’d never had to seek a job before. After commencement at Yale in 1963, I’d gotten a call from James Henry Brewster, IV, a friend of mine in Skull & Bones.

“Gates,” he said assertively, “I’m setting you up at J. Walter Thompson.”

Jim was working for Pan Am Airways, the largest airline in the world at the time, and a major client of J. Walter Thompson’s, the advertising firm known as JWT in the business. The two of us had a good time together at college—wouldn’t it be a gas to work together now!

Jim set up the interview. When I went in to meet the people at JWT, I was confident of my chances. Not only did I have the “in” through Jim, but the owner of JWT, Stanley Resor, was another Yale man. His son, Stanley Resor, Jr., had roomed with an uncle of mine at Yale. I had visited the Resor family at their two-thousand-acre ranch out at Jackson Hole just the summer before.

These connections proved invaluable. Advertising was regarded as a glamorous profession. Television commercials had just taken off, and become humorous and interesting. Lots of people wanted to get into a business in which you could make plenty of money but also have a creative edge. JWT’s training program was regarded as the best in the business, and it hired only one or two copywriters a year.

I was one of those hires.

It had been love at first sight. All I had to do was talk and write—skills that came naturally to me—and they paid me amazingly well for it. I was good at my job, and the clients appreciated my creative ideas.

I also found that I enjoyed making presentations, and doing them in original ways to bring some life and laughter into what could be really boring meetings. For example, because we had created the line “The Marines are looking for a few good men,” we were asked to pitch for the Department of Defense’s multimillion-dollar recruiting account. The presentation was held in a war room at the Pentagon. As I walked in, I saw a row of bemedaled men sitting behind a high table. These were the Joint Chiefs of Staff. They sat like stone statues, clearly unhappy that they had been dragged into such a frivolous marketing meeting.

I walked up to the front of the room, carrying my portfolio case. I reached inside and pulled out a bow and arrow. Someone else from my team walked to the opposite end of the room with a target I had drawn with Magic Marker on a piece of Styrofoam. I wanted to dramatize the fact that we believed in targeted advertising. I wanted to speak with a tool to which these military men would relate: a weapon. I also wanted to make sure that since we were the first of thirteen agencies these men would be seeing, they would remember us.

I pulled back the arrow, and let it go. By the grace of God, it hit the bull’s-eye. For a minute there was dead silence in that room. No one moved. No one spoke. Then all four military leaders broke into applause, and there were a few cheers, and laughter. We won the account.

In addition to liking the work, I worked extremely hard. There was a sign-in sheet in the lobby of the JWT office building in New York, and I always tried to be one of the first to sign in and one of the last to sign out. I received promotions early and often, moving from copywriter to creative director and executive vice president on a host of major accounts, including Ford, Burger King, Christian Dior, the United States Marine Corps, and IBM.

I was willing to go anywhere to help our clients. JWT was an international company that expected you to be willing to travel nationally and internationally. I had no hesitation in uprooting my growing family—somehow between ads I had found time to marry, have a two-week honeymoon and, in due course, four children—moving to work in offices in Toronto, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. I looked at work as a big part of my role of being a good provider for them. When it came to family, no sacrifice was too much. As such, JWT became my top priority.

Yet, in a terrible irony, I flew many hundreds of thousands of miles to spend time with clients, and hardly saw my children. My clients became my children, and my children grew up without me. Was that really my pudgy baby, Annie, now a beautiful young woman graduating from high school? It brought tears to my eyes to see her accept her diploma, looking so grown-up and so ready to leave home, and leave me. I realized with a pained clarity that I had missed so many precious moments with her, and with all my children.

And yet I convinced myself—even then—that the sacrifice was worth it, because JWT had supported me. My salary was high and my benefits were excellent, so now that the kids were moving on to college and the bills were about to become even more insane, I didn’t need to be terribly concerned. In the back of my mind, I even congratulated myself: This is why you were smart to dedicate yourself to one company—the stability and the pay. Like many men of my generation accepting of the role of “breadwinner,” I rationalized my devotion to work and trust in JWT.

Loyal to a fault, I worked even longer hours, always ready to adjust my personal schedule for my clients’ needs. I remember getting a phone call from the Ford client one Christmas Day when my kids were little. I had just been getting ready to spend a rare day at home, having a chance to play with Elizabeth, Annie, Laura, and Charles and enjoy a few relaxed moments of being a real family, and being a real family man. The client wanted to do a New Year’s sale event, and could I shoot some commercials? Ford loved beating up on the agency, and since they spent millions of dollars on ads, they never made you an offer you could safely refuse if you valued your job.

“Sure,” I answered. “When?”

“Now,” he said.

I heard those emphatic words and knew I had to go, leaving my children in tears. Their presents were just unwrapped, spread out on the living room floor, and everyone was still in their pj’s. But I was a loyal JWT man. I got a taxi to the airport and flew to Detroit.

I was full of pride that I had never refused any effort JWT ever asked of me. It was a true shock, then, when twenty-five years into my career, I received a call from young Linda White, a senior JWT executive.

“Let’s have breakfast tomorrow,” came her directive.

Those aren’t good words to hear from a colleague. I liked Linda. A few years earlier, I had convinced the old boy network that we needed an intelligent young woman. Linda had done well, and I had helped get her on the Board of Directors. The only woman on the board. In fact, Linda was now president, having passed me in the corporate hierarchy.

She was a favorite of the new owner of JWT, a Brit named Martin Sorrell whose bookkeeper background made him particularly attentive to the bottom line. Before Martin arrived, JWT was almost like a nonprofit organization, dedicated to doing the best communications for our clients and not worrying about the bottom line. Martin had a different idea. He told the stockholders he was more interested in boosting their profits than in spending to achieve the highest caliber work. He made a hostile bid for our company. We fought him, but Martin had the Wall Street bean counters on his side, and he easily prevailed.

I had been in a meeting when Martin said bluntly, “I like young people around me.” I really should have listened to him and seen what was coming.

Martin himself was only in his early forties. Linda was in her early thirties. No wonder they got along. Young, smart people, they were eager to get rid of whom they probably felt were “the old farts.”

On the morning of our breakfast, Linda showed up late. Another bad sign. In corporate America, the higher your status, the tardier you are. Consciously or unconsciously, Linda had adopted the style.

She had red eyes. It looked like she had been crying. Yet another bad sign. I knew that Linda liked me and felt some gratitude to me for helping her career, but I also knew that in modern corporate life there was no time for sentimentality. The facts that I was still good at my job, and was honest, and had spent my whole adult life helping JWT become successful were irrelevant.

I had met Linda at a party. She had just graduated with an MBA from Harvard and held an undergraduate degree in history of art. As I told her, it was a winning combination in advertising—she would be strong in creative ideas, while making sure the whole process made a profit. And I had been right. But her credentials alone would not have gotten Linda hired. I had to present her as more macho than any other guy we could hire. In helping Linda move into the top management of JWT, I had written a memo describing her as an “unforgiving high achiever.” I had shown the memo to Linda.

“Am I really that unforgiving?” Linda asked me, almost hurt.

“No, maybe not,” I said. “But as a female high achiever you have got to be perceived as tough as any male—especially in management. Probably tougher than you really are underneath. Macho number crunching, including crunching people, is the management style Martin really likes.”

I had helped Linda focus on the hard substance of the business: money, and an unforgiving attitude toward cutting “overhead”—which in advertising was always people. Now the overhead was me.

I smiled at her over the table. I wasn’t going to cry. Yet I felt like dying. My heart actually hurt. Was I having a heart attack? No, I just felt really, really sad. And angry with myself. Why hadn’t I seen the signs? Linda went forward and upward in her career at JWT; I stayed in place. Linda passed me flying. Martin liked Linda. In a polite, British way, it was clear Martin could not stand being in the same room with me. With my sparse white hair, I was an embarrassment to the kind of lean, mean, hard-charging, young company he wanted to run.

“Michael,” Linda said, “I have some bad news.” I fiddled with my muffin, willing myself to meet her eye.

The waiter came up to me to see if we needed anything else. Waiters still think that the old guys have the money and run the show.

I shook my head, and he backed off.

“Let me have it,” I said stoically. I wasn’t going to beg for mercy. I knew it would not do any good. I hoped that Linda had at least argued for me, for old times’ sake. But by the time you got to a breakfast meeting, outside the office, the deal was done. I knew I was history.

“We have to let you go, Michael.” She pronounced the words robotically. To her credit, she had a hard time getting them out, especially that phony corporate “we.”

“It’s not my decision,” she hastened to add, and a tear started down her cheek. She brushed it quickly away, embarrassed by her own emotion—particularly in front of a guy who had taught her to be so tough. I don’t think she was acting. I think she was genuinely unhappy that I had been fired, and that she had been chosen to do the dirty deed. From the bottom-line point of view, it was, as they said, a “no-brainer.” Plenty of young people could write and speak as quickly and well as me—for a quarter of the cost. If Linda had refused to fire me, then she could not be part of the management mafia. It was a test of where her loyalty lay: to an old creative guy who had helped her in the past, or to a young financial whiz who now ran the company? Linda had to prove to Martin that she was unforgiving. You had to kill to get in the mafia. Linda would make her bones this day.

I was brave as I could be. At least for those few minutes with Linda.

Linda told me that I would get paid a week of my current salary for every year I had spent at JWT. She was sorry it was not more, adding that she was sure I had saved something during all the good years.

Fat chance! I said to myself. I have a house full of kids to educate!

My mouth was dry. I couldn’t talk.

“Okay,” Linda said, rising. “It’s not necessary for you to go back to the office to pack up. We’ll handle that.”

The “we” again. Linda was ready for prime-time.

“I want to have a going away lunch for you, Michael, you’ve contributed so much,” Linda said, standing. “I will call you to set that up. And Jeffrey Tobin in Personnel will see you whenever you want to go over all the details of your severance package.”

The thought passed through my mind of suing JWT, or writing nasty letters to all the clients. But Martin and Linda had already thought of that. “You will probably want to become a creative consultant of some kind,” Linda continued, her tone more positive now, “and Martin and I would, of course, give you fabulous recommendations. I will personally help you in any way I can,” she added. I was dead at JWT, but she was willing to keep me on some kind of life support, if I was a good boy.

Being fired is not the best way to start a consulting company. Yet I knew I needed the goodwill of JWT to have any chance of getting business from my old clients, or anyone else. If I caused trouble, I was trouble, and I’d never get any work.

The pesky waiter came up again, and I waved him off again.

Linda gave me a squeeze on both arms, almost—but not quite—a hug. “Be sure and call Jeffrey, Michael. He likes you. He will help you as well.”

Then she turned quickly and strode out of the restaurant.

The waiter returned, one last time, and presented me with the bill.

Outside, the sun was shining. I suddenly, desperately realized I had nowhere to go. For the first time in twenty-five years, I had no clients waiting for me to make sense of a communications campaign. I started walking and found myself crying on the street. It was humiliating. Crying! Me! Yet at fifty-three I had just been given a professional death notice. I knew in my heart it was going to be a bad time to be old and on the street.

And so it turned out.

Yes, I’d like a job. I hadn’t said those words for thirty-five years. It had been thirty-five years since I had taken my entry-level job at JWT. And it had been ten years since I had been fired from my high-level position at JWT. I had set up my own consulting company, and I got a few good jobs right away from my old clients. Then, slowly but surely, fewer and fewer of my calls were returned. It had been months since my last project. Even a latte was becoming a luxury I could no longer afford.

Now, looking across my latte at this confident, smiling Starbucks employee, I felt sorry for myself. She seemed carefree to me, so young, so full of options. Later, I would learn that she had seen more hardship in her life than I could conceive of having seen in three lifetimes. Her mother, who died when she was just twelve, was a dope addict. She had never known a father. When her mother overdosed, she had been sent to live with an aunt, another single mother, who already had several of her own fatherless children to care for. Her aunt was an aunt from hell. She would later tell me of the horrifying time she had fallen down the cement stairs of the project in Brooklyn where she lived. Her hip was broken, but her harried aunt just screamed at her for being so clumsy and refused to send her to a hospital. The bone set, but in a terrible way that guaranteed constant pain. Despite the confidence that she projected to me that day, she was even then in pain, physical and emotional.

But at that moment I was still at the center of my own universe, and my own problems were all-consuming.

To me, this young woman had great power—the power to employ me. Yes, I would like a job. As soon as the words had come out of my mouth, I was horrified. What was I doing? Yet, at the same time, I knew I wanted a job. I needed a job. And, I presumed, I would easily get a job at this Starbucks store … or would I?

The Starbucks employee arranged the papers in front of her, her smile disappeared, and she gave me a hard look. “So, you really want a job?” she said incredulously, shaking her head. She had clearly become more ambivalent about me as we got into the real possibility that I might work for her.

It suddenly struck me: Her invitation to a job had been a kind of joke. Maybe she had just decided to pass a few minutes making fun of me, the boring, uptight guy who seemed so full of himself. Maybe she had acted on a dare from another employee. But to her surprise, I had taken her up on her invitation.

She eyed me skeptically. “Would you be willing to work for me?”

I could not miss the challenge in her question: Would I, an old white man, be willing to work for a young black woman?

She later confided to me that her angry, bitter aunt had told her repeatedly as she was growing up, “White folks are the enemy.” From her point of view, she was taking a risk in even offering me a job. She was not willing to go an inch further until she was sure I would not give her any trouble.

I too was ambivalent. The whole situation seemed backward to me. In the world I came from, I should have been the one being kind enough, philanthropic enough to offer her a job, not the one supplicating for the position. I knew that was a wrong sentiment to feel, terribly un-PC, but it was there nonetheless, buzzing under the surface of the situation. This young woman clearly didn’t care if I said yes or no to her job offer. How had she gotten to be such a winner? My world had turned upside down.

New York City, 1945. My parents always seemed to be going out to cocktail parties and dinners. I was a lonely little boy. As usual, they were not home when I returned on the bus from Buckley School, but there was Nana, as always, waiting for me with arms outstretched and a big smile on her face. I rushed into her commodious bosom.

This old woman who lived with us in our imposing brownstone on East Seventy-eighth Street was the love of my young life. She was my family’s cook and my closest companion. I spent all of my time with her in the warm and delicious-smelling basement kitchen, imitating Charlie Chaplin and making her laugh. She gave me delicious treats of nuts and raisins. When her father in Virginia was sick, I told her that she should go back to see him. Two weeks later, her father died. Nana thought I was “sent by God.” She told me I would be a man of God someday, a preacher. I had buck-teeth and big ears, but Nana said, “You are a handsome boy.” She told me I was going to be a real heartbreaker.

Later, I overheard my parents talking in the library. Their voices were low. I crept up to the door to hear them better.

“Nana is getting too old to climb the stairs,” Mother said.

Our brownstone had four floors, with seventy-three steep stairs—I’d counted them many times to ease my boredom.

“Yes, I think it is all becoming too much for her,” Father agreed.

My heart dropped with dread. They must not let Nana go. I ran to her, crying, but couldn’t tell her what I’d heard.

Weeks later, when I came back one afternoon from school, Nana wasn’t waiting for my bus. She was gone. Mother had hired a refugee from Latvia to be our cook. She was nineteen, and Mother told me she was doing a good deed in hiring her. The Latvian worked hard, but she barely spoke any English and didn’t talk to me, or even look at me. And she was scared to go near me, or anyone else, which I learned much later was because the Nazis and the Communists had raped her.

But, as a young child, I only understood that Nana was gone, and I was alone again in the big house. The kitchen was cold and bare without her, yet I didn’t want to leave the room where she had been. I sat quietly on the kitchen windowsill and watched the raindrops racing down the glass. I picked one raindrop to beat another to the bottom of the glass. If I picked the right one, I told myself, I deserved to have a wish come true. Then I wished that Nana would come back.

Less than a hundred yards from the brownstone I lived in from the ages of one to five, as I applied for a job at Starbucks, I was suddenly feeling the hole in my heart for a woman I hadn’t seen for almost sixty years. Nana had been much older than the Starbucks employee facing me today. Nana was loving and large and soft. This young woman was professional, small, with a great figure. Nana had several gaps in her warm smile. This young woman’s smile was a perfect, dazzling white. Nana was like a mother to me. This woman had already made clear she would relate to me as a boss to an employee.

There was really nothing these two women had in common—except they were both African-Americans. Like so many white people I knew, I appreciated the idea of integration, and yet, the older I got, the more it seemed that in my Waspy social circle, white people stuck with white people, black people with black people. For me to relate to an African-American woman on a personal, honest level opened memories of the only truly close relationship I had ever had with an African-American woman.

This young Starbucks employee did not realize that because of Nana, I was emotionally more than willing to work with her—I could not help but trust her. It was an irrational feeling, I told myself. How could a sixty-three-year-old man be influenced by an emotion from the heart of a four-year-old child—but there it was. Would you be willing to work for me? she had asked.

“I would love to work for you.”

“Good. We need people. That’s why we’re having an Open House today, and I’m here to interview people for jobs as baristas.” She barely looked at me as she told me these facts. It was as though she were reading me my Miranda rights instead of selling the job. “It’s just a starting position, but there are great opportunities. I never even finished high school, and now I’m running a major business. Every manager gets to run their own store and hire the people they want.”

She handed me a paper.

“Here is the application form. Now we will start a formal interview.”

She reached out her hand.

“My name is Crystal.”

The whole time, I had still been sitting with my latte and papers at my corner table. My briefcase on the table fell to the ground as I rose awkwardly partway out of my seat, shook her hand, and said, “My name is Mike.”

I had called my business Michael Gates Gill & Friends because I was in love with the sonorous sounds of my full name. But here I felt that “Mike” was the better way to go. The only way to go.

“Mike,” Crystal said, once again shuffling the papers at the table before her, still not looking at me, “all Partners at Starbucks go by their first names, and all get excellent benefits.”

She handed me a large brochure.

“Look through this and you will see all the health benefits.”

I grabbed the brochure eagerly. I hadn’t realized the position offered health insurance. Rates had gotten too high for me to afford my health insurance, and I had let it go, a mistake that I had recently found out might have serious repercussions for me. Any remaining ambivalence I had about the job went out the window.

Just a week before I had had my annual physical with my doctor. Usually, he gave me a clean bill of health. But this time he shook his head slightly and said, “It is probably nothing, but I want you to have an MRI.”

“Why?”

“I just want to make sure. You said you had a buzzing in your ear?”

“A slight buzzing,” I hastily replied. I never gave Dr. Cohen any reason to suspect my ill health. I never even told him if I was feeling ill. He was a great practitioner of tough love—which meant that he was relentless in finding anything wrong with me.

“Slight buzzing. Buzzing!” he said in his usual, exasperated way. He was impatient with my artful dodging. “Get an MRI, and then go see Dr. Lalwani.”

“Dr. Lalwani?” That did not sound encouraging.

“Michael, you are a snob,” Dr. Cohen told me, “and that could kill you someday. Dr. Lalwani is a top ear doctor. He got his doctorate at Stanford. That make you happy?”

After a lifetime of treating me, Dr. Cohen knew me too well.

I had the MRI. Dr. Cohen had told me that it would only take a “few minutes.”

I lay there for at least half an hour. And I also did not like the fact that I heard other doctors come in and out of the room.

“What’s going on?”

“Nothing,” the young orderly told me. “We will send the MRI up to Dr. Lalwani. He wants to see you.”

I was angry. Angry with Dr. Cohen for insisting on this stupid MRI. I had been healthy all my life. And I was not about to stop now. I could not afford any ill health.

Dr. Lalwani kept me waiting for most of the afternoon. I saw people go in and out of his office. Finally, Dr. Lalwani appeared, smiling from ear to ear. Was that a hopeful sign? Lalwani gestured me into his office. It was small and cramped and piled with papers. Not reassuring. I would have preferred a large corner office, with a comfortable couch. He was obviously not doing that well in his profession.

“Mr. Gill,” he said.

“Michael,” I told him, trying to be kind.

But he was insistent, smiling harder. “Mr. Gill, I have some bad news for you … but then you knew something must be wrong … am I correct?”

I knew something must be wrong? Was he crazy? I thought everything was all right.

“What are you saying?” I could barely contain my anxiety and my rage at his calm demeanor.

“You have a rare condition. Fortunately, it is in an area that is a specialty of mine.”

“What is it?” I almost shouted, but Dr. Lalwani was not to be rushed.

“Something very, very rare.” He smiled again. “Only one in ten million Americans.”

I waited, filled with anger, but also with an animal sense I had to let the good doctor do it his way. I was already scared enough to yield to his academic style.

“You have what is called an acoustic neuroma. My specialty. But very rare. It is a small tumor on the base of your brain … that affects your hearing.”

For a second I could not see or hear anything. It was as though I had been given a blow directly to my head and heart. I think I might have stopped breathing.

Dr. Lalwani, sensing my extreme distress, hurried on.

“This condition is not fatal,” he said. “I can operate. But I must tell you the operation is very serious.”

I recovered sight and sound just in time to hear those ominous words. “Serious” coming from a surgeon was not something I wanted to hear.

“What do you mean?”

“We bore into the skull, and it is an operation on the brain. Literally, I am a brain surgeon … this is brain surgery.”

He was so confident in himself. I hated him for being so willing to operate.

“Your hearing may not be restored. The tumor is causing the buzzing. It will take one or two weeks before you can leave the hospital,” he said.

“Before I can leave the hospital,” I repeated numbly.

“And several months before you will be fully recovered. But the rate of recovery is very high. Fatalities are very rare. Only a few actually die.”

A few … die? Was he mad?

“When do I have to have the operation?” I stammered out. My mouth was dry.

“I would do it right away … but you might wish to wait several months, come back, we will have another MRI, see if the tumor has grown. You might have a very slow-growing tumor.”

Finally, a ray of hope. Like everyone, I hated the idea of hospitals. Friends had died in hospitals. Not to mention I was broke. Any postponement was a gift from God.

I got up quickly, shook his hand, left his office, and immediately called Dr. Cohen.

He was not reassuring.

“Sounds like you should have the operation,” he told me.

“Yes,” I said, faking agreement, “but I will wait a few months for another MRI.”

I was buying time.

Giving up health insurance for myself was bad enough, but not to be able to afford health insurance for my children was much worse. I wondered if the tumor was in some karmic way a punishment for my behavior.

Now, sitting across from Crystal, I read the Starbucks brochure about the insurance benefits with particular interest They seemed extensive, and even covered dental and hearing—something I had never been given as a senior executive at JWT.

I looked up at Crystal, hopeful, “Does this cover children?”

“How many kids do you have?”

“Five,” I said, thinking about how I was used to saying “four.” Five.

Crystal laughed. Then she smiled, almost kindly.

“You’ve been busy,” she said.

“Yes.”

I did not want to say any more; it was way too complicated to explain in a job interview.

“Well,” she went on, still with a positive tone, “your five kids can all be covered for just one small added deduction.”

What a relief. My youngest child, Jonathan, was the main reason I was so eager for work. It wasn’t his fault. It was all my fault.

I had met Susan, Jonathan’s mother, at the gym, where I had started to go shortly after I was fired. I needed a reason to get out of the house every day, and exercise became my new reason for getting up and out.

One morning I had been lying down on a mat resting. I was in a room that happened to be empty at the moment and was occasionally used for yoga classes. Susan had come in. It was clear she did not notice me and thought the room was empty. She was crying as she moved over to lean against the wall.

“Are you okay?” I asked. I was uncomfortable around emotional people.

She was startled, but did not stop crying.

“My brother is dying of cancer … just days to live …”

“That’s tough,” I said, sitting up on my blue mat, getting ready to leave.

“And just last year I lost my father to lung cancer.”

“Tough,” I repeated, standing up. I should have continued my progress out of the door, but I did not feel I could just leave her with her sorrow.

I moved closer to her.

“Don’t worry,” I said, not knowing where these words came from. “You will soon be happier than you ever have been before.”

She looked up at me. Susan was small, barely more than five feet, with lots of dark hair and brown eyes. I am over six feet tall, with little hair and blue eyes. We were a study in contrasts, an odd couple for sure.

Susan rubbed her tears away, but more kept flowing.

“What?” she said, not quite believing that she had heard correctly.

I could not believe what I had said. Where had those crazy words come from?

But I repeated them.

“You will be happier than ever.”

She nodded, as though understanding at some level.

I turned to go.

“I like a man who does yoga,” she said. “It shows flexibility.”

Susan and I started our relationship on totally false assumptions. She had taken me for someone interested in yoga. I had no interest in yoga. I did not like to stretch: It made me feel even more inflexible. I was rigid about many things. Physically. Mentally. Emotionally. I liked old songs, old ways. Until now, my past had worked well for me. Susan had no idea about what I was really like. Meeting me in the yoga room, she thought I was a flexible, perceptive person who could understand the deeper, more positive profundities of life. Like I was some wise guru.

It is funny, sometimes, how wrong people can be.

Susan was so wrong about me, and I was so wrong about Susan. I took her for a sad waif, a person who needed comfort and protection. Yet I learned later that she was an accomplished doctor of psychiatry with a large group of enthusiastic patients.

I thought she needed me.

She thought I could help her.

We were both so wrong.

Yet there was an immediate attraction between us. Was our powerful chemistry proof of the saying that opposites attract? Especially early morning in a gym. I had nothing better to do. And she had two hours free before she had to see her next patient.

Since I had been fired, I had found it impossible to make love to my wife, not that we tried that often. Like many married couples, we made love only occasionally. Still, it had scared me when I had tried to perform last time and failed. That physical failure compounded my recent professional failure. I had always counted on sex as a joyous release. Now it was one more sign of my seemingly irreversible decline.

Until I met Susan.

Yet, despite the attraction, I moved to the door. I was inflexible, and did not have affairs … especially with people I met at a less-than-exclusive gym.

“Would you like to have a cup of coffee?” Susan asked gently as I moved toward the exit. I almost did not hear her. She spoke so softly.

I found myself saying, “Sure, let’s have a cup of coffee.”

What could be the harm in having a cup of coffee with a sorrowful little person? We could get a latte at Starbucks and I could cheer her up.

But instead of Starbucks, she suggested her apartment. I went with her, and I was hooked. After that, I saw Susan almost every morning when she was free—which was two or three times a week.

Susan was not that young. In her mid-forties. She told me that her gynecologist had told her she could not have babies. So she said she saw no point in getting married.

“Marriage is for having kids,” she said. “Sex is better without the bonds.”

“Not to mention you already are married,” she reminded me, glancing at my ring to confirm the fact.

I acknowledged her point with a significant amount of guilt. I loved how Susan made me feel, but I wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I loved my wife and wanted my four kids to live in a stable family environment.

Then one morning Susan called me at home—something she had never done before.

“I have to see you.”

“When?” It was seven-thirty A.M. I had not even had breakfast.

“Now.”

She was standing naked in her apartment; the curtains open to the East River. It was a March morning, but the sun was bouncing off the water.

“Michael,” she whispered, “I’m pregnant. And God has told me I should have this baby.”

My heart stopped. This was not on my agenda. I had lost my job and was struggling just to support my own family. I did not need another child.

“What are you thinking?” she asked.

“You have got to decide,” I said.

“Tell me.”

“No,” I said, getting up. I was not going to tell her to have an abortion. This might be her only chance for a child.

“It’s a miracle, Michael, but I need your support.”

“I’m broke.”

She laughed. Susan had another misapprehension: She thought because I dressed well and seemed well off that I was rich. She had no idea that behind my Ruling Class attitude I was getting poorer every day.

I had kept my relationship with Susan secret, but when Jonathan was born, I told my wife. She could not stand it.

“An affair is one thing,” she said. “A child is another.”

Betsy is very clearheaded.

“I just can’t do it,” she told me. “I’m not made for this kind of thing.”

So we got an “amicable” divorce, although she was rightly furious with me for being so stupid.

“I thought we would spend the rest of our lives together,” she said. I felt terrible.

My kids, now practically grown-ups, were understanding in a grown-up way, but hurt and angry too. I had given Betsy our big house, and she had enough family money to be okay, but I knew it wasn’t just about money. I had ruined her life.

And ruined my own life as well.

I took a small apartment in a New York City suburb. Desperately wanting to do the right thing after doing all the wrong things, I resolved to try to be there for Susan and my new child, Jonathan. I would come by around four or five A.M. and play with Jonathan so Susan could have a little sleep.

I was doing it out of a sense of obligation. But an unexpected thing happened. I became more and more attached to Jonathan. And he to me. Together, Jonathan and I would watch the dawn. When my other children were young, I did not have the time to watch them catch the wonder of each new moment. I was working twelve-hour days at JWT.

Here, I was being given another chance to be a father—in many ways, an opportunity I didn’t deserve. I loved to see Jonathan grow before my eyes; to watch as he waved his little hand as though conducting when I would sing a gentle song, or hear him laugh with such uninhibited delight when I threw a stuffed animal up in the air.

One day, when I was putting my sleeping baby back in his crib, Jonathan opened his eyes and smiled at me. He opened his mouth and out came the beautiful sounds “Da da.” Two simple, heartbreaking syllables. Thinking back to how I had missed such magical moments with my other children caused a physical pain in my chest. And for what? For a company that rewarded my loyalty with a pink slip. I wanted to sit each of my children down and instruct them: You only live one life; take it from me, live it wisely. Weigh your priorities.

I spent less and less time chasing new clients, and more and more time with Jonathan. He loved me and he needed me. I was somebody wonderful in his eyes.

Jonathan seemed to be the only one who felt that way these days. Susan had gradually lost interest in me, first as a conversationalist. She told me I was “boring.” I was not open to new ideas. And then she lost interest in me as a lover. She told me I was “too routine.” In a peculiar way, the more available I became to her—after divorcing my wife, and having fewer clients and work to do, more time on my hands—the less appealing I was to her. She imagined me as a man at the top of America, fulfilled, productive, successful, and happy. She got to know me as I was: an insecure little boy not that good at dealing with reality.

Jonathan was my last fan, and my best pal. But now he had started spending his days in school, so I was left with more time on my hands, fewer excuses for not finding work, and a greater need for a job just for bare survival. Hell, I wasn’t even providing my little boy with health insurance.

How had I managed to be so incompetent in all of my personal and professional relationships? I tried to clear my mind of all my guilty, negative thoughts and focus on Crystal and this surprising interview. By luck or on a whim, Crystal had given me a chance—maybe my last chance—to stop my downward spiral. I did not want to blow it.

I looked up at Crystal and tried to give her a confident smile.

She wasn’t buying it. It was clear that Crystal was balancing a personal dislike for me with her commitment to being a professional. Her store was in desperate need of new workers. And I was desperate for work. Convince her, I told myself. Convince her that this is a match made in heaven. I willed myself to be positive.

“Now I want to ask you some questions about your work experience,” Crystal said in a cool professional tone.

I was suddenly very worried. After finding out about the health benefits that Starbucks offered, I really wanted this job. Was Crystal going to be another young woman like Linda White who would end up cutting off my balls? I didn’t care, so long as she hired me.

“Have you ever worked in retail?”

Her question startled me.

I tried desperately to think…. Quick, what is retail?

“Like a Wal-Mart?” she helped. I sensed, for the first time in the interview, that Crystal might have decided to be on my side. This whole thing had started as a joke or a dare with her, but maybe, just maybe, she had come to see me as a person who really needed some help.

It suddenly struck me how much a life of entitlement had protected me from the reality everyone else knew so well. Maybe Crystal could help me get a grip, yet I could not even grab the saving rope she had tossed me in this job interview: I had never even been inside a Wal-Mart.

Crystal made a little mark on her paper and moved on. I felt very nervous. This was not going well.

“Have you ever dealt with customers in tough situations?” Crystal read the question from the form and then looked up at me. But her eyes were softer; now she seemed to be willing me to answer this question correctly.

Yet I was still at a loss. Was it tough to talk to the CEO of Ford? Yes, but that wasn’t what was going to get me this job. I remembered that I had done advertising for Burger King and had worked at a store one morning to get a feeling for the business.

“I worked at Burger King,” I said.

Crystal gave me a big smile.

“Good,” she said. “And how did you handle a customer when things went bad?”

“I listened very carefully to what they were saying, then I tried to correct what was wrong, and then I asked them if I could do anything more.” I spouted gibberish from some forgotten brochure I had written on how to handle bad situations.

Crystal smiled again and made a mark on the paper.

“Have you worked with lots of people under tough time pressures?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, keeping it vague. Working late on an advertising campaign for Christian Dior was different from serving lattes to hundreds of people on their way to work.

Crystal ticked down the list. “What do you know about Starbucks? Have you visited our stores?”

I was off and running. During my job seeking over weeks and months, I had been in many Starbucks around New York. I leapt at the opportunity to show my knowledge. “The Starbucks stores in Grand Central are always busy, and none have seats, so I can’t sit down, but the store on Fifth Avenue at Forty-fifth Street is really comfortable, and the one at the corner of Park Avenue has a great view, and—”

“Okay, Mike,” she said, cutting me off, “I get it.” She smiled. “Since you seem to be a fan, I think you’ll like this question: And what is your favorite drink?”

Once again, I was able to be honestly enthusiastic. I love coffee in many forms, and Starbucks was my favorite place to get it.

“What’s the difference between a latte and a cappuccino?” Crystal asked.

Here she had me. I liked both drinks, but did not know the difference. “I don’t know…. The cappuccino has less milk or something?”

“You’ll learn,” she said, marking my form again, but I thought that response was positive. Just her saying “You’ll learn” was a confidence builder for me. I had almost given up on the thought that I could learn or do anything new, or that anyone would invest the time in helping me learn a new job.

Crystal stood up. The interview was clearly over.

I stood up as well, almost knocking over my latte in my eagerness. We shook hands.

“Thanks, Crystal,” I said, being as thankful as I ever had been in my life. She must have sensed the true gratitude behind my everyday words.

She laughed. What was so funny about what I had said? She was obviously now just getting a kick out of the whole situation. And me. Maybe I had shown her that the “enemy” was someone she could easily handle. Or, even better, maybe she had discovered that I was not just an old white man, but also a real person whom she could help. Whatever the reason, she seemed much more relaxed with me.

But then she got serious again. “The job is not easy, Mike.”

“I know. But I will work hard for you. I promise you this.”

She smiled, and maybe there was a little bit of pride in it. Later, I would learn the reason. Eight years earlier, when she had been on the street, she could never have conceived that in the future, she would have a Waspy guy, the proverbial “Man” himself, all dressed up in a two-thousand-dollar suit, begging her for a job.

Crystal must have recognized the sincerity in my willingness to cross over the bar—from drinking lattes to serving them up. But I realize now that she must have also seen that I still had much to learn, and many preconceptions to shed.

Despite this, she was willing to take a risk, cross over class, race, and gender lines, and consider me for the job.

“I will call you in a few days, Mike,” she said, “and let you know.”