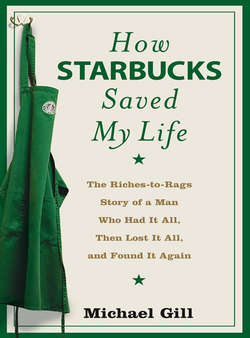

Читать книгу How Starbucks Saved My Life - Michael Gill - Страница 9

Оглавление3 One Word That Changed My Life

“The human catalysts for dreamers are the teachers and encouragers that dreamers encounter throughout their lives. So here’s a special thanks to all of the teachers.”

—a quote from Kevin Carroll, a Starbucks Guest, published on the side of a Decaf Venti Latte

MAY

I stood at the Bronxville station waiting for the 7:22 train to New York. I was not due to start my shift until 10:30 that morning—but I wanted to give myself more than enough time. The train from Bronxville to Grand Central took at least thirty minutes. The shuttle from Grand Central was another ten to twenty minutes to Times Square. From there I would jump on an express up to the West Ninety-sixth Station. I could then walk just a block or so to my store. I was anxious. I had not mastered the commuting routine and did not want to be late. I did not think I could afford any mistakes at my new job.

Waiting on the platform on that May morning, I had a chance to look around Bronxville. The little suburban village had changed a lot in the last few days as April showers heralded May flowers. Like in the movie The Wizard of Oz, the black-and-white winter had gone and the spring colors had arrived. There were now masses of bright red and white tulips everywhere—almost garish in their profusion. The forsythia was a burst of yellow. The trees had that first green tint that was like a soft mist against the brightening blue morning sky.

I sighed and then out of nowhere began to cry softly. The tears silently ran down my cheeks as I tried to suppress them. I did not want to draw attention to myself in that mass of energetic commuters. The men and women all seemed to be dressed in Brooks Brothers suits and were bubbling with a kind of self-congratulatory exuberance that I now found sickening.

I was jealous of them for their confidence about their lives.

I hated them for the ease with which they seemed to face their commute.

I knew I was relatively invisible to them. Dressed in my black pants, shirt, and Starbucks hat, I looked like what I was—a working guy. Just another of those people who showed up at odd times to join the commuter rush—but were heading for service jobs too menial for the Masters of the Universe to notice.

I tried to brush the tears away, but they would not stop. Maybe it was an allergy from all the pollen now filling the air? But I knew it was not.

There was something so incongruous and sad about my standing on that platform waiting for a commuter train in my uniform so many decades after I first arrived in this exclusive town. My father had decided, after my mother had several more children (it seemed to me that my father was anxious for another son, that I was a real disappointment to him, and that was why he kept trying) that we had to leave the city.

My father chose a huge Victorian mansion in Bronxville because it was close to the city and a good public school. But Bronxville was not a happy place for me.

Every single day when I walked to school, a bully named Tony Douglas would leap out from behind a bush, push me down, and twist my arm until I cried. It was humiliating to cry at eight or nine, but I could not—eventually—resist. I knew crying was the only way to get him to stop. He really hurt me. He scared me. It was like he might break my arm. In the winter he would push my face down into the snow and rub it until I begged him for mercy. I had to beg to get away from him. Then he would leap up and run away laughing. I would slowly rise, in real pain, trying to gather up my books.

Not that I could read. That was another reason that I was so unhappy in Bronxville. When I got to school, I was in for more daily humiliation. Try as I might, I could not learn to read. I really tried. All my classmates learned. It was terrible to be sitting there in the midst of my classmates and not see what they could see and not be able to speak out loud the words that they could so proudly speak. The words in the books the teachers gave me to read seemed to be created in some secret code that I could not break. The sentences jumped before my eyes. I tried to will myself to break the code, but could only guess what those black lines meant.

How horrible it felt to me to be alone in this public proof of my stupidity, my obvious inability and misery.

My failure was impossible to ignore.

Miss Markham was the principal in the elementary school. She was a terrifying figure. Dressed in a black suit, she would march down the halls issuing commands in a deep voice.

I was brought to her attention.

She called my parents to come in and speak to her.

My mother was embarrassed; my father was clearly angry. I had ruined his day.

“Why couldn’t she see us at some other time?” my father asked my mother. “It’s right in the middle of my morning!”

For some reason Miss Markham took my side. Somehow, she had decided, despite all the signs to the contrary, that I would turn out all right. She also had insisted on including me in the “parents” conference.

“I never talk about children behind their backs,” she explained.

Right in front of me, she told my parents, “Michael will read when he wants to. Stop badgering him.”

I was dumbfounded by her attack on my parents. For she was clearly very cross with them. I had always been told how wonderful my parents were. She seemed to feel that I should be protected from them in some way.

Her apparently irrational faith was eventually justified, although reading came to me not through any act of concentration or panicky desire, but just gently, easily, one summer in the country when I was ten.

Every summer we would leave Bronxville for a small country town in the mountains of Connecticut. Mother was much happier there. She had gone to Norfolk for summers when she was young, and there were still many friends from her youth who summered there. Her best friend from childhood had a house just a few fields away, and her son became my best friend. We would ride our bikes down the old dirt roads and go for swims in the little lake.

Mother would get me out of bed early in the morning so I could see the dew sparkling in the sun.

“Elves’ jewels,” she would say, hugging me with delight. “Is there anything more beautiful in the world than a summer morning in Norfolk?”

Sometimes she would get me out of my bed at night after I was asleep and take my hand and lead me out to look up at the moon.

“Isn’t it glorious?” she would say, a happy lilt in her voice.

But my happiest memory was sitting with Mother on a steamer rug while she read to me. Across the field I could see a group of birch trees. Their leaves would flutter in the soft breeze…. One moment they would be green, and then silver in the bright sun of a late summer afternoon.