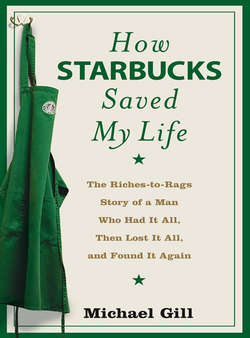

Читать книгу How Starbucks Saved My Life - Michael Gill - Страница 8

APRIL

ОглавлениеSeveral agonizing weeks went by, and I heard nothing further from Crystal. Every moment I was consciously or unconsciously waiting anxiously for her to call. I continued going to the Starbucks store at Seventy-eighth and Lexington where we had met, hoping to catch sight of her, but she was never there.

I also kept calling potential clients for my marketing business, but my voice mail remained empty. More than ever I needed a job, any job. When I had first met Crystal, I was not terribly serious about the idea of working at Starbucks. But over these last weeks, waiting for her call, without any other options surfacing to give me hope, I had realized that Starbucks offered me a way—perhaps the only way—to handle the costs of my upcoming brain tumor operation and support my young son and my other children. To support myself. I was facing the reality, in my old age, of literally not being able to support myself. I had left my former wife with our large house, was down to the last of my savings, and now I was facing the prospect that I might not be able to meet next month’s rent. I was even more desperate than I had been just a couple of weeks ago. Whenever my phone rang, I found myself almost praying it was Crystal.

Had I done something wrong during the interview? I wondered. Said something wrong? Or was I just the wrong gender or race or age for Crystal to want to work with me?

As I sat willing the phone to ring, I thought back to casting sessions for the television commercials I had created over the last decades. I had not hesitated to eliminate people for any imperfection. If an actor’s smile was too bright, or not bright enough, if a young lady had the wrong accent, that person was dismissed. When hiring, I chose the people who were like me, with backgrounds like mine. Now, as the days went by and Crystal still did not call, I had a sinking feeling that maybe Crystal operated in the same way: Do the easy thing, stay clear of anybody different.

“Diversity” is a big word these days. But few that I knew ever really moved beyond their own class or background—especially in hiring people they might have to work with every day. In corporate America, diversity was an abstract goal that everyone knew how to articulate, but few I had known actually practiced it. Rather, it was simply a word we discussed in a vague way when the government might be listening.

My only hope was that Crystal needed new employees enough—or was courageous enough—to give me a chance. Wasn’t it ironic that I was hoping Crystal would be more merciful than I?

I forced myself to stop thinking about it. Then, one morning when I was in Grand Central Station, my cell phone rang.

“Mike?”

“Yes?” I answered with some suspicion. The person on the other end didn’t sound like anyone I would know.

“It’s Crystal.”

My guarded attitude changed instantly.

“Oh, hi!” I said enthusiastically. “So good to hear from you!”

“Do you still want a job …,” she paused, and continued coolly, “working for me?” It was as though she were eager to hear a negative response and get on with her day. I imagined she had a list of potential new hires she was working through. And most of those on the list were probably easier for her to imagine working with than me.

“Yes, I do want to work with you,” I almost yelled into my cell phone. “I am looking forward to working with you and your great team.”

Calm down, Mike, I told myself. Don’t be overenthusiastic. And why had I said “team”? Crystal had talked about “partners.” I knew that every company had a vernacular that was important to reflect if you wanted to be treated well. I was already going crazy trying to fit in. Take it easy, I said to myself, or you will blow this last chance.

It didn’t seem to matter—Crystal didn’t really seem to be listening. You know how you can be talking to someone on the phone and sense that they are pretending to listen to you while doing something they feel is more important? I felt that way that day with Crystal. For me, this phone call was of crucial importance. To her, it was just another chore in a hectic day.

The casual way in which she offered me the job was humiliating.

“Okay,” she said. “Show up at my store at Ninety-third and Broadway at three-thirty P.M. tomorrow.”

“Ninety-third and Broadway?” I echoed, surprised by the address.

“Yes.” She sounded like she was instructing a three-year-old. “Ninety-third … and … Broadway, and don’t be late.”

I was confused. “But we met at Seventy-eighth and Lex.”

“So?” She was almost threatening. “I met you there ’cause we had a hiring Open House going on. That’s the way we do things at Starbucks.”

Crystal had taken on a tone I knew well. I had used this corporate by-the-book attitude when dismissing people I did not want to deal with.

“At Starbucks,” she continued, “we pick a store, have an Open House, and the managers who need people interview. But that doesn’t mean that’s the store you will work in. I’m the manager of the store at Ninety-third and Broadway.” She paused, and added, “Do you have a problem with that?”

Once again, the threatening tone. Yes or no? She had other people to speak to and was eager to complete this call. I could sense she was not enjoying this job offer.

“No problem,” I hastened to assure her. “I’ll be there tomorrow, and on time.”

I sounded—even to myself—like an old guy speaking like a new kid at school. How embarrassing!

“If you want to work, wear black pants, black shoes, and a white shirt. Okay?”

“Okay,” I answered.

She hung up. She did not even say good-bye.

Shit! That little call made me feel really depressed. In the last few weeks, as the reality of my hard life grew clear to me, to keep depression from overwhelming me I grasped at straws—any signs that I might have a chance to maintain my position at the top of American society rather than drop so precipitously to the bottom rungs. Through these days of waiting for Crystal to call, the prospect of working at Starbucks humiliated me, but I told myself at least I’d be working in the neighborhood I had grown up in. A nice neighborhood. A location that would help me in my transition from a member of the Ruling Class to a member of the Serving Class. In the midst of my obvious, impossible-to-deny fall from financial and social heights, Seventy-eighth Street was a comforting place to be.

I had never even been to Ninety-third Street and Broadway—wherever the hell that was. My policy in New York City was never to go above East Ninetieth Street or below Grand Central. Now I was going to be working in what I envisioned could be a very dangerous neighborhood. It was certainly far from the Upper East Side, where I felt at home.

And I also didn’t like Crystal’s attitude toward me. She acted as though I were some dummy. I felt how unfair she was being. Then I remembered with remorse that I had treated a young African-American woman who had once worked for me at JWT with exactly the same kind of dismissive attitude. Jennifer Walsh was part of a big push we made in the 1970s to hire minorities. It was our token—and short-lived—effort at diversity.

Simply because she was part of this minority-hiring initiative, Jennifer was suspect to me. I was supposed to be her mentor. Yet, until that moment in Grand Central after talking to Crystal, I had never experienced what it was like to be so casually dissed because of my different background. I realized with a sinking heart how casually prejudiced of anyone different I had been in my reactions at JWT. At the agency, we liked the fact that most of us had gone to Ivy League schools. We thought we were the elite of the advertising business. We all approached the idea of hiring anyone who hadn’t gone to the crème de la crème of universities as lowering the status of our club—and that included many in the minority-hiring initiative.

Jennifer was nice, but she had graduated from some minor junior college with a two-year degree, and I never took her career at JWT seriously. I had told her to read ads for several weeks, not even to try to write one. Then I had given her a newspaper ad to write for Ford. Her very first ad.

Jennifer came into my office. It was clear that she was scared, even petrified, as she approached my big desk. Which made me feel that she was wrong for JWT; we had to project self-confidence to our clients. I blamed Jennifer for being insecure in this new circumstance. When I read her draft of an ad, I noticed that she had copied a whole paragraph from some other Ford ad I had given her to read. This was a form of plagiarism that we really hated at JWT. Perhaps because we were called copywriters, we could not stand anyone who was accused of actually copying someone else’s work. Jennifer had just committed an unpardonable corporate sin. At least as far as I saw it.

Thinking back, I realize that she might not have known that this was against policy, and I certainly didn’t point it out to her then. I literally did not give her error a second thought. Her stupid mistake gave me the excuse I needed. I went to management and told them that Jennifer might make a great secretary someday, but she did not “have what it takes” to master the higher art of advertising. I had no time for her, or the idea of diversity.

I realized with a kind of horror now, recovering from Crystal’s casual handling of a job opportunity that meant so much to me, how casually cruel I had been in “helping” Jennifer. I had been a classic hypocritical member of an old boys’ club, congratulating myself for my belief in minority advancement in the abstract, while doing everything possible in the practical world of the workplace—which I controlled—to make such opportunity impossible. I had consciously or unconsciously derailed Jennifer’s attempt to penetrate my little world just because she was an African-American without the education or experience that mattered to me.

Jennifer had been moved into some clerical job in Personnel, and had gone from my mind until this very moment. Now I felt terrible. I imagined Crystal thought I was some dumb old white guy whom she mistakenly offered a job. I wouldn’t fit into her world or be a good match for her needs—just as I had felt about a young black American woman several decades ago.

I also kicked myself for not listening to my daughter Laura over many years. Laura had a beautiful halo of brown hair that echoed the sparkle of her hazel eyes, and I had a picture of her now shaking her head in angry frustration as I refused to “get it.” She had devoted much time to trying to introduce me to a more realistic view of the world, and because I had been so insensitive, I had failed to listen to her. Laura had a dynamic, positive energy; she laughed easily but she also had a feeling for how unfair life could be and as she grew up had adopted African-American causes like affirmative action. She would sit across the table from me during dinner and toss her beautiful curls in frustration as we argued. I had dismissed Laura’s feelings and ideas of how to help others less fortunate as “hopelessly naïve.” I had been secure in my bubble of self-congratulation: convinced that my top job in advertising and my resulting affluence were my just reward for being a great, talented guy … not simply status and success virtually given to me by birth and fortunate color in a world ruled by “middle-aged white men of your generation,” as Laura had once phrased it. Laura and I had a kind of running argument when she was growing up. It seemed like from the time she was about ten years old, she took my whole affluent lifestyle as an affront when so many people had so much less.

Even though she was now at college, she had not lost any of her sympathy for people less fortunate. She had actually cried when I had dropped her off at the picture-perfect campus I had picked for her.

“What’s wrong?” I asked her. I had worked hard to get her into this particular college, even calling up a trustee I knew to put in a good word.

“This place has no diversity,” she had said, struggling to express her frustration with me and my attitude of entitlement as she gestured at the all-white group of freshmen streaming into a fancy, newly built dorm she was to inhabit. “You still don’t get it!”

Now I realized with a painful awareness how wrong I had been to try and stifle Laura’s view of the “real world” as unfair to those not born in the right class with the right skin color who could afford the right higher education. I felt an actual pain in my heart at that moment, realizing with regret my arrogant assumption that God had created me and those like me to rule because we were worthier than other races of people. Now, finally, I was “getting it” as I faced a new reality of what the world could be like without inherited advantages.

But was my hard-won knowledge too late to change my fate?

Maybe there was bad Karma, I thought to myself. I certainly deserved it. But I was not about to turn down Crystal’s offer—whatever her attitude.

I woke early the next day and realized with a shock that I was just weeks away from my sixty-fourth birthday. They say April is the cruelest month, and as I struggled into my black pants for my Starbucks job, I shook my head in disbelief that I was probably going to celebrate my birthday by working as a lowly coffee server.

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at my feeling of trepidation as I hurried from my inexpensive apartment in suburbia and leapt on a train to Grand Central. Then I ran as fast as I could with the mass of people for the subway shuttle over to Times Square. Even though there would be another shuttle in a few minutes, we stampeded toward the one in front of us as though it were our last opportunity to go anywhere that day. I could not believe how fast the crowd moved—it seemed like we were in a hundred-yard dash for some Olympic event. Why rush? I hadn’t commuted to a job for years, and back then I had taken a taxi or a company car as I moved up in the privileged hierarchy of JWT. I had never been one of the people who took subways. Yet now I had no time to doubt the sanity of the forward motion—I rushed along with everyone else.

From Times Square, I transferred from one crowded train to another that was heading up to Ninety-sixth Street. Squeezing in just as the door was closing, I found myself pressed against people I would never want to know; forced into a kind of primal physical proximity. All faces were unfriendly. How did I get to this place in my life? I thought to myself. Soon the doors opened, and I was forced out onto the dirty platform. I climbed the steep stairs to Ninety-third Street with a pumping heart, beginning to sweat, although it was a cold day in the beginning of April.

Emerging from the subway, I struggled against the wind and then actually staggered as I approached the Starbucks store at the corner of Broadway. Icy rain made the pavement slippery. I paused. Now that I was there, I was in no hurry to open that door.

As I stared at the Starbucks sign, the reality of my situation hit me with a sickening impact. I felt numb, standing on the icy pavement in the wrong part of town. My dream of rejoining a big international company to become rich and in control and happy once again had turned into a humiliating nightmare. Yes, I was going to join a big international company, but in reality as nothing better than a waiter with a fancy name. I would have the very visible public embarrassment of being Michael Gates Gill dressed as a waiter serving drinks to people who could have been my friends or clients. It was like the old days when the Pilgrims put sinners in the stocks in the public square as a visible example to others to watch their ways.

The Puritan minister Jonathan Edwards had said: “We all hang by a thread from the hand of an angry God.” Maybe there was an angry Puritan God who had decided to punish me for all my sins. Over every minute of the past few years, I had felt the heavy weight of guilt for hurting so many I loved. My former wife, my children, and even those few friends I still had. My Puritan ancestors would be raging at me. Yes, I thought to myself, maybe there really was a vengeful God whom I had offended.

Yet I had to admit that my reality was more mundane, and sad. I could not pretend that I was living out some kind of mythical biblical journey. I was not a modern Job; I was looking for a job. And I had to face the brutal yet everyday fact that I was here because of my own financial mismanagement, my sexual needs that had led me to stray. I was not some special person singled out for justice by God. I was, and this really pained me to admit, not even that unique. It was hard, terribly hard, for me to give up my sense of a special place in the universe.

Now I was forced to see a new reality: What I was experiencing, as a guy too old to find work, was a reality for millions of aging Americans today who could not support themselves and were no longer wanted by the major corporations in our country. In this state of numbed anxiety, ambivalence, and forced humility, I opened the door to the Starbucks store.

Inside, all was heat, noise, and a kind of barely organized chaos. There was a line of customers almost reaching the door. Mothers with babies in arms and in prams. Businesspeople checking cell phones. Schoolkids lugging backpacks. College kids carrying computers. All impatient to be served their lattes.

As I looked behind the bar at the servers of the lattes, one of my worries was confirmed: Virtually all the Partners were African-American. There clearly was no diversity. This was not a complete surprise to me, because I had noticed in visiting various Starbucks locations since my interview with Crystal that very few white people worked at any of the New York stores.

For the first time in my life, I knew I would be a very visible member of a real minority. I would be working with people of a totally different background, education, age, and race.

And it was also clear from what was going on in the store that I would be working extremely hard. There were three Starbucks Partners strenuously punching at the cash registers taking the money and speedily, loudly calling out the drinks to other people at the espresso bar. The people at the bar called back the drink names, while quickly, expertly making the drinks, juggling jugs of hot milk while pulling shots of espresso. In rapid-fire order, they then served them up to the customers with an emphatic “Enjoy!” that was almost a kind of manic shout. The customers themselves would reach in for their drinks with a fierce desire.

This coffee business clearly was not a casual one to anybody—on either side of the bar. There was a frantic pace and much focused noise, like being part of a race against time. I had never been good at sports, and this store had that athletic atmosphere of people operating with peak adrenaline. With all the calling and re-calling of drinks, it seemed that I might be auditioning for a role in a kind of noisy Italian opera.

Suddenly I was very worried. Not just about race or class or age. Now I had an even more basic concern. I had originally thought that a job at Starbucks might be below my abilities. But now I realized it might be beyond them. This job could be a real challenge for me—mentally, emotionally, and physically.

I had never been good at handling money—it was a major reason I needed a job so badly now. Math was a subject I had never mastered at school. I had vivid memories of many math teachers claiming, “But this is so easy,” as they scratched out some equation on the blackboard. I hated those teachers for their superiority. Even the simplest additions and subtractions were a challenge for me. Now the reality of all that money changing hands so rapidly at the Starbucks registers terrified me.

I had lost hearing in one ear due to my brain tumor. Hearing the complicated drink orders could be a serious problem for me. I was also scared by the idea that I had to understand tricky orders and call them out correctly in a matter of split seconds. Languages had never been my skill. My French professor at Yale had said, “I will pass you on one condition: You never inflict your accent on anyone else in this university.” Yet it was clear I was now expected to master the exotic language of Starbucks Speak.

In that first instant, I realized with humiliation that my new job might be a test I could easily fail. I had worn the black pants with a white shirt, no tie. I was feeling lonely and afraid. Then Crystal appeared in a swirl of positive energy.

“Let’s share a cup of coffee,” she said, guiding me over to a little table in the corner. “Sit here, I will bring you a sample.”

Maybe this was just Crystal’s public, professional attitude, but I was grateful for it. She seemed much friendlier than on the phone. Perhaps, I thought, she had come to terms with hiring me and did not hate herself or me for taking this chance.

Soon I was sitting down in a small corner with Crystal and sipping a delicious cup of Sumatra. “This is a coffee that is known as having an ‘earthy’ taste … but I call it dirty.” Crystal laughed, and I laughed too. Today Crystal had her hair up under a Starbucks cap, making her look very sophisticated, even glamorous. Two bright diamond earrings caught the light.

Maybe it was the coffee, more likely it was Crystal’s ability to put me at my ease, but I was feeling a lot better.

Still, I was a long way from being comfortable. Out of nowhere, I had a sudden image of myself in a long past life, basking in the comfort of family and friends on a dock on a lake in Connecticut. Now that image of laughing and lounging so comfortably beneath a warming sun seemed like several lifetimes ago. The lake I had grown up on was protected by thousands of acres of private forest. It kept out the reality of a harsher world and surrounded me with fun and privilege.

I remembered as a young boy throwing apples at the poet Ezra Pound. Jay Laughlin, Pound’s publisher, owned the camp next door and had brought Pound down to the lake for the day. Pound sat like a kind of statue at the end of the dock. At one point he rolled up his suit pants and dangled his white legs into the water, still not speaking. His legs looked like the white underbelly of a frog. There was something about Pound’s proud strangeness that got to my young cousins and me. We picked up some apples we had been eating and started throwing them at him, missing him but sending up water to splash against his dark, foreign clothes.

Ezra Pound did not move or speak. My father laughed and kind of encouraged us in our behavior. My father had written a bestselling book, Here at The New Yorker, about his years at the magazine. In the opening, he had stated his philosophy: “The first rule of life is to have a good time. There is no second rule.” Having a good time for my father meant upsetting apple carts. He had no love for Pound’s politics and enjoyed the scene.

My father had won his place on this lake by marrying into my mother’s family, who had vacationed there for a hundred years. My father brought new money, earned by his Irish immigrant father, into her Mayflower ancestry. At the lake there was a powerful combustion of gentle Wasp politeness meeting up with my father’s purposefully provocative Celtic rebel style. With a kind of self-righteous abandon my father joyously spent the money his father had worked so hard to earn.

“It is better to spend your money while you are still alive,” my father would declare, his black eyes flashing with a kind of devil-may-care enthusiasm, seeming to mock his own father’s hard-won acquisition and those uptight Yankees around the lake who pinched every penny.

My father loved to speak, he loved to write, and he loved, above all, to be the center of attention at parties. “Everything happens at parties,” he would say. So there was a constant party on our dock at this exclusive, rustic lake.

My father was a spendthrift with his time as with all his many talents. He gave himself away to so many that there was never enough time at home for me. Never enough time for one-on-one, for father and son. When I was grown, and I moved away from home, he invited me to his parties, and that is the only way we saw each other. When he died, my need to go to parties died as well.

Now I found myself sipping coffee with Crystal—worlds away from the parties during those summers on that exclusive lake—yet as I laughed with her, I could actually feel my heart become a little lighter and my spirits rise a bit. This reality surprised me. Maybe it was the caffeine in this powerful coffee. But I also had to admit that I felt at ease in this totally new scene—having coffee in a crowded, upbeat bar as a way of beginning a new job. It was all so bizarre and foreign, like Alice through the looking glass. Or Michael Gates Gill breaking through to another place and class to find it wasn’t so scary after all. I was stepping out from my old status quo, and as a direct result, I felt better than I had in days. Or weeks. Or months.

It was crazy … but maybe, I hoped, there was a method in this madness.

Crystal’s voice broke through my daydream. “Mike, it is important you learn the differences in these coffees.” I no longer had the luxury of time for philosophical self-concern. The bell had rung. I was in the ring. It was time to get involved in minute-by-minute efforts rather than heavy contemplation. Keeping up with customers’ orders was my new job. I had to give up spending so much time thinking about the past and what I had lost. It was going to be a big challenge just to keep up with the present.

I was about to discover that at Starbucks it was not about me—it was about serving others.

Crystal had a serious look on her face and launched into a lecture as though I were some eager student of coffee lore: “Sumatra coffee is from Indonesia; the Dutch brought it there hundreds of years ago, and it’s part of a whole category of coffees we call ‘bold.’”

“We” again, I noticed, thinking back to Linda White and her “we” when she had fired me. Crystal could do the same.

“This is the way we welcome all new Partners,” Crystal explained, leaning forward toward me as though to confide a great personal secret. “We believe that coffee is our business. Starbucks Coffee is our name. So we welcome all new Partners with coffee sampling and coffee stories.”

Crystal sat back with a smile, and I smiled back at her. Her face now seemed so positive and cheerful. Even her brown eyes, which could be so cold, now seemed to sparkle with a kind of happy interest. It had become clear to me as she talked that she was intelligent and even passionate. At least about the coffee business. And I felt that maybe—just maybe—Crystal really was going to give me a chance to prove myself.

As I sampled the rich Sumatra brew, I was beginning to feel that I could handle this part of the Starbucks business. I loved coffee; I loved learning about the history of things. I glanced over at the Partners behind the counter, all working hard yet seeming to have a great time. While they were all so young, and while there was not a white face in the bunch, maybe, I told myself, I should be, like the coffee I was drinking, part of the “bold” category.

Then the store door swung open. In stepped a scowling African-American guy, well over six feet tall with bulging muscles under a black T-shirt. He was wearing a do-rag wrapped tight around his head that, to my eyes, made him look like a modern pirate. He had a mustache and some sort of hair thing happening on his chin. He was the kind of person that in the past I had crossed the street to avoid.

Crystal called to him, “Hey, Kester, come over and meet Mike.”

Kester walked slowly over to our table. I noticed a bruise on his forehead. He reached out a big hand.

“Hi, Mike,” he said with a low baritone. And then he smiled. His smile transformed his whole face. Immediately, I felt welcomed. In fact, he seemed much warmer than Crystal. Why? Was this because he was much more confident he could handle me? Old white guys definitely didn’t bother him.

“Kester, where did you get that?” Crystal said, pointing at his forehead.

“Soccer.”

“Soccer?”

“Yeah, some of my friends from Columbia got me into the game…. It turns out they think I’m pretty good. A natural.” Kester laughed when he said that.

But Crystal quickly got back to the business at hand. Her face took on what I was coming to know as her hard, professional look. I got a sense Crystal always liked to be in control. “Mike is a new Partner,” she explained to Kester, “and I was wondering if you could do me a favor…. Would you be willing to be his training coach?”

I was to learn that nobody at Starbucks ever ordered anyone to do anything. It was always: “Would you do me a favor?” or something similar.

“Sure,” Kester replied, “I’ll change and be right back.”

After he left, Crystal told me, leaning forward in her confidential way, “Kester never smiled until he started working here. He was leader of a group of bad …” She stopped, seeming to be conscious of telling me too much. She leaned back, adjusting her hair. She had so many moods. Confiding. Confidential. Serious. Cheerful. Professional. Wary. Now she was wary again.

Kester returned, dressed in a green apron and black Starbucks cap, yet still looked pretty intimidating … until he smiled. Crystal got up and gave him her seat.

“I’ll bring you two some more coffee.”

Crystal returned with a cup of Verona for each of us and some espresso brownies. I was surprised by the enthusiastic way she served us. I had never served anything to any subordinate in all my years in corporate life. But Crystal seemed to be genuinely enjoying the experience. She and Starbucks seemed to have turned the traditional corporate hierarchy upside down.

She launched into a detailed description of Verona, telling us it was a “medium” blend of Latin American coffees, perfect with chocolate.

“But, then,” Crystal explained, giving us both a big smile, “all coffees go well with chocolate; they’re kissing cousins. You’ll like the taste of Verona with this espresso brownie.”

She left us to enjoy our coffee and brownies. It was as though we were guests in her home. It was certainly a totally different experience than any I had been expecting. The Verona coffee with the espresso brownies was a delicious combination—Crystal was right.

Then Crystal brought us a Colombian coffee with a slice of pound cake.

“This is in the ‘mild’ category,” she said. “Can you taste the difference?”

“It sure seems lighter than Sumatra,” I said.

“Right, ‘lighter’ is a good word, Mike,” she said, as though she were a teacher congratulating an apt pupil. “Don’t worry, you’ll learn all about lots of different coffees here. By the way, you are going to be paid for the time you have been sitting here drinking coffee and having cake with Kester. Not bad for your first day on the job!”

Crystal left me with Kester. Though she had seemed so relaxed, I realized it might be just part of her management style. She was probably just putting a “new Partner”—me—at my ease. I realized Crystal was hard to read, and that it would take me a long time to really get to know her. She didn’t fit into any of my neat categories.

Ten years earlier, I couldn’t have imagined being so frightened and so eager and so desperate for this young woman’s approval.

And ten years ago, I couldn’t have imagined having espresso brownies, cake, and cups of coffee with someone like the physically intimidating Kester.

“Here’s how it works,” Kester said matter-of-factly. “We call it training by sharing. It just means that we do things together. I learn from you by helping you learn.” He picked up my cup in his and stood up. “Okay, now that you’ve had your coffee, I’ll show you how to make it.”

I followed him behind the bar.

Later, I came to know that Kester was the best “closer” at Starbucks. Closing the store late at night is one of the biggest management challenges because you have to be responsible for totaling up all the registers and making sure everything is perfectly stocked for the next day. Kester always made sure he got everything done on time and done right.

I didn’t know any of this on my first day on the job. I also did not know that one late night, months later, Kester would save my life.