Читать книгу I Closed My Eyes - Michele Weldon - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Fiesta Forever

ОглавлениеMoving to Dallas in July might not have been the best idea. It was blow-dryer hot every morning and suffocating at night. The evening we stepped off the plane and into a life together, it was 103 degrees. I learned not to touch the steering wheel of the car after it had been in the sun for more than an hour, and I set the thermostat in my apartment on Gaston Avenue to 64 degrees. The city seemed strange in its sounds and its smells, its small town-ness and its hulking, empty glass buildings. People talked differently in sharp, slow Southern accents. The pickup trucks had gun racks. There were drive-through beer barns and jokes about Yankees.

But I had work that was nearly perfect, writing stories that filled me, and experiences that were new, meeting almost every new experience with a man who loved me. The people I met at the newspaper were like characters from a play. I had a column called “Michele Weldon’s Glitter Gulch Gossip,” so I was invited to parties, concerts, openings, balls. I wrote feature stories and profiled celebrities I flew around the country to interview. I wrote about authors, actors, advocates, anyone in the eighties with an idea to push or a product to sell. From a distance, my life was charmed. I even spent a week in a suite at the Savoy Hotel in London filing stories about the marriage of Margaret Thatcher’s son, Mark, to Diane Burgdorf, the daughter of a Dallas businessman. I was happy.

What could go wrong? For the most part, there had been an ironed, protected smoothness to my life and the lives of the people I knew. With few exceptions, I was not struggling; the pieces came into place as expected. For someone who moved through the world predictably, with a gelatin ease, there is a danger of being insulated and oblivious, of being blind.

It will all be perfect, I thought. I will have this perfect job and this perfect boyfriend and this perfect life. He will become a perfect husband. I will be the perfect wife.

My boyfriend rushed to fill the still, dark, vacuous holes left by the absence of my family and my close friends. Like water pounding into an empty cavern, he flooded the spaces of my life and did not leave me air to breathe. I thought it was love.

He wanted to be near me every second. I craved his company, his closeness, his attention. We would talk a dozen times a day, have lunch together, meet for dinner. Delirious and young, we would kiss and plan and dream, planting the passion for a lifetime that would be as good as we dreamed. He read my stories in the paper and came to all the black-tie dinners in a tuxedo he bought secondhand just so he could be with me. Sometimes he was called Mr. Weldon at events. He said it didn’t make him that mad.

He got a job immediately in Arlington, Texas, at a small daily newspaper on a recommendation from one of my professors at Northwestern University. It was a thirty-minute commute to Dallas, and he lived in an apartment on Pioneer Parkway with a loft and a stubborn population of roaches. But it was an adventure, our adventure.

I missed my girlfriends and my family. I missed my parents, my sisters, and all the birthday parties for my growing school of nieces and nephews. He was thrilled to be away from his family, and from mine. “Now we can work on our relationship alone without the pressures of your family,” he said.

“Your parents hang on every word you say,” he told me once after a dinner with my mother and father at the Drake Hotel’s International Room before we moved. “It’s disgusting. Your mother finishes your sentences, and your father sits there as if everything you say bears the wisdom of Buddha.” He said he was repulsed.

“They get a kick out of me,” I said.

It turned into a circular argument about the kind of person I would become if everything I said was treated with such blind reverence. I ended up apologizing and saying that I knew he was only trying to make me a better person. I dismissed the notion that he was a jealous ass.

Over the months and years, he met my friends, and they mostly liked him and thought he was suitable enough, if a little intense. When Dana, my roommate and closest friend from college, visited from Los Angeles, he was nervous, awkward. He later told me it was because he wanted to kiss her, that she was beautiful and exciting. He told me he loved me so much he could be completely honest with me. “All men really think this way,” he said. I was furious, but I guessed I never knew a man as sincere.

Lorraine, who became my closest friend in Dallas, worked at the newspaper with me and lived two doors down in an apartment complex on Gaston Avenue. She and I spent hours talking about him by the apartment pool and debating if he was the right one. What did we know? We both decided he was worth the minor trouble: his possessiveness, the jealousy he denied but was there nonetheless, the intense arguments out of nowhere about nothing that lasted hours. I mean, he was cute.

Lorraine and I compared him to my brothers, her brothers, our male friends, old boyfriends. He came out ahead on some of the criteria and fell short on others. Still, he was a nice boy from a nice family. What could go wrong?

Lorraine and I both thought it was strange, though, that he called her and a handful of my other women friends when I didn’t come right home after work one night. I’d gone to the Galleria in North Dallas to do spur-of-the-moment shopping, which Lorraine knew (I’d told her on my way out of the office) and explained when he called her, frantic. I was gone two hours, tops.

By the time I got home, he had left a half-dozen messages on my answering machine. Lorraine first thought it was weird, then said, no, he’s really protective, he’s just concerned about you. I never went anywhere again without telling him exactly where I was. I didn’t want him calling everyone in the phone book every time I went to Saks Fifth Avenue for a sale.

I told myself I had nothing to hide, that he was welcome in every inch of my life. He wants to be part of my life, all of my life. I must really be wonderful. Nobody has loved me this much. We started talking about marriage.

One year after we met, the first Christmas that we lived in Dallas, he asked me to marry him. He gave me a white gold and diamond ring with a large stone in the center, diamond baguettes and sapphires on the side. It was his grandmother’s, a keepsake of his mother’s mother, and his mother had helped him to get a larger diamond—one carat—placed in the center. I loved it; it was part of his family, and through it, I felt part of his family. I had known his sisters and brothers my whole life. My mother had given bridal showers for his sisters, and to his parents I had offered cold shrimp with toothpicks at dozens of parties in my parents’ living room. His father was funny and his mother was beautiful. I wanted to be loved by them.

His proposal was planned and ritualistic, not a surprise. After both of us flew from Dallas home to Chicago together for the holidays, we arrived at my parents’ house in River Forest and retreated to the basement. I sat on the yellow chintz couch, and before me he knelt down and said he would love me forever. He asked me to marry him, pulling the ring from a blue velvet box in his gray tweed coat jacket. I put it on my finger, and then he called my parents downstairs to tell them the news I had told them months before. They’d just been waiting for the signal.

My father hugged him and then me, calling me “Mich,” the way he had when I was little. My dad walked over to the bar at one end of the wood-paneled basement and from the wine cellar pulled out a small, dusty bottle of red wine, dated 1958.

“Here, Mich, I bought this for you when you were born. I have been saving it for tonight.” I was astounded that this gentle, gracious man had moved this bottle from house to house, placing it high on a shelf and remembering the gift he would one day give me, his fourth daughter, his sixth child. He loved me enough to hold a secret for me and to share it when it would be the most special.

We toasted each other with raised glasses, and I took pictures, my father with his arm around my new fiancé, both of them smiling as wide as monkeys. Here are the two men I love most in the world, I thought. How could I be so lucky?

My mother hosted an engagement party a few days later, with an accordionist, my husband’s family, my family, great food, and champagne. We took a lot of pictures and set the date for October, the Saturday before Columbus Day. My mother and I talked about Waterford patterns and bridesmaids’ dresses.

We catapulted on, young and determined, making plans, working hard. Months passed. He seemed edgier, more tense, but blamed it on another new job, this time as a reporter for a small weekly business newspaper in Dallas as a reporter. On April 4, six months before the wedding, he told me he could not get married now. To say I was not devastated would be a lie. He said he still loved me and wanted to marry me eventually, but I told him I would only wait six months, and I gave him back his ring.

“Don’t let me hate you,” I pleaded with him when he pulled away after dropping me off at my apartment that night.

I see it now as the first in a litany of betrayals, yanks of control. He later said he felt out of control of the wedding and wanted it to be more about what he wanted, about us and less about ritual. I guess he resented the Waterford pattern my mother picked. I guess he disapproved of the invitation’s script. I couldn’t sleep well for days and stayed awake wondering how I got here, how he could have made such a rash decision alone when it was about me, about us. I was so confused. The dream was fading.

My sisters Mary Pat and Maureen came to Dallas the first weekend after he canceled the wedding, an ambassador’s visit to cheer me up. We went to dinners and I tried to be brave. I tried not to cry, but my heart was shattered. There were days I forgot to eat. I worked long hours and went home and watched tv. I made a lot of long-distance calls. His sisters wrote me kind letters.

As the weeks and months passed, I became less angry and more trusting. I tried to go on a date with another writer I had met and spoken with at parties, but I made it just for lunch. Still I felt dishonest, as if I owed my boyfriend my loyalty. He moved here for me. We’ve been together for nearly two years. He loves me; he only asked me to wait. I didn’t want to lose him.

I will do what he wants.

It was the first time I forgave him for hurting me, and it was certainly not the last. I never understood his reasons; nothing dramatic had happened. We continued to date, though mostly on Saturday afternoons; anything else seemed false. Yet he still called me his fiancée whenever I was introduced to his friends or someone from work. I was confused. My editor at the newspaper called it classic cold feet.

In early September, a few days shy of my six-month deadline, he asked me if I would wear his grandmother’s ring again. I said I would only if we set a date and if he would not change his mind. I would not forgive him a second time, I said.

I did not want to be engaged forever. I had known women who had been engaged for five, six, seven years, only to have their fiancés go on vacation, meet a woman skiing or on a beach, and marry her a month later. I was not going to be a fool. We set a date; he was convinced now it was the right thing, and we targeted our lives toward August 23, 1986. He seemed sincere. I told my parents. My father said he would have to talk to him in person before he agreed. I was still on schedule, though, still on the marriage square.

It will be all right. He will be the perfect husband now. There will be a happy ending.

We went together to Marshall Field’s in the Galleria to pick out the china: Villeroy & Boch, a cream pattern with peach marble trim called Sienna. He had opinions on the crystal, Mikasa, and the silver, 20th Century from Reed & Barton. We toiled over the booklet for the wedding, Psalm 88, “With my chosen one, I have made a covenant,” was his choice for the front cover. An artist friend of his drew two doves beneath a cross, an image borrowed from one of my favorite passages from William Shakespeare’s King Lear: “We will sing like two birds in the cage.” Then I saw it as a symbol of love and commitment.

Three of his friends who were priests—an old friend from his childhood, his roommate from college, and a friend from the seminary—all stood on the altar and helped to concelebrate the mass. People joked that there were almost as many priests as groomsmen.

I later wrote an essay about our wedding for Bride’s magazine: “We had a church wedding followed by a formal, seated dinner for 230 people. Like the many inner circles of a tree’s bark, friends and relatives formed rings around the dance floor. There were cousins, aunts, and the girls I have been friends with since the age of eight. My parents’ close friends were there, as were friends of his family. I had never felt as happy or loved—not only by my groom, but also by my parents, his parents, and all the smiling faces in that room wishing us well.”

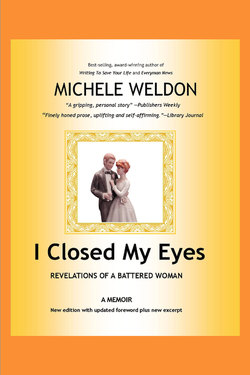

Our wedding photograph was published in Town & Country magazine alongside a collection of other black-and-white photographs of attractive, jubilant couples. While he smiled, handsome and bright, his pose always struck me as odd. He had a tight grip across my left hand, covering all my fingers as well as his grandmother’s wedding ring. It is a forceful hold, and in the photograph I look oblivious. I wonder now if any of those other couples there in those pages with us, captured in a yesterday of bliss, have felt this kind of pain. I hope not. I pray not.

I gave him a gold wedding band with the inscription “Fiesta Forever” after our favorite Lionel Ritchie song, “All Night Long,” the one we heard on our first date. He lost his wedding ring a year or so later at the health club, and I replaced it with another gold band with another inscription. He lost that too. I didn’t bother to have an inscription on the third.

But that Saturday afternoon in August 1986 was perfect. We walked down from the altar, freshly wed, where he had cried at our vows, tears falling to the tops of his cheeks. Then he raised his hand in a fist and held it there, the defiant, jubilant conqueror, as the string quartet in the balcony of Saint Vincent Ferrer’s Church in River Forest, Illinois, played “On Eagle’s Wings.” I tugged at his arm, embarrassed, but let him go. He was impulsive, after all.

I didn’t know that he was telling the world that he now had control over me. He had won. It was a sign, like the thousands of other signs I chose not to see. It was a sign that for the next nine years he would continue his pose as the conqueror, as the victor, and I as his victim.

It was the signal that I was now married to a man who would tell me he wanted vacuum marks on the rug when he got home from work. Who would tell me driving home from the doctor’s office in 1988, where I found out I was pregnant with our first son, that with this news he was sure my mother would now control our lives. This man would later tell me that my job was to take care of the house and the children and that everything else in my life, including my work and my writing, was mere distraction.

Here was a man who would hit me on Christmas Eve. Here was a man who would hit me when I was pregnant with our first son. This man would tell me he didn’t want my friends from high school in our house. And here was the sign that the man I thought was perfect would wound me more physically and emotionally than anyone I would ever know.

“Please, God, let me kill her,” he said nearly ten years later, six months before I obtained the emergency order of protection that led to the end of our marriage.

But that August afternoon, with my friends waving and smiling and the photographer taking pictures, I entered into a life I could not have prepared for. This man’s presence would later make my stomach tighten and my heart pound just by hearing his key turn in the lock. This man would loathe me.

Here was a sign. But I only saw the handsome man in the gray-striped cutaway morning suit telling the world he loved me and that he was triumphant. He won me. I was the prize.