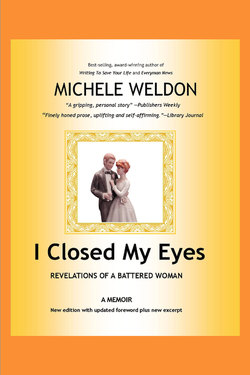

Читать книгу I Closed My Eyes - Michele Weldon - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

Оглавление“Will you ever forgive me?”

His voice was familiar, plaintive, beckoning in its mock sincerity. But now I was keen and unwilling to erase all that had come before. I knew this voice too well, the somber, innocent voice, the one that always comes after, the one that sometimes comes right before. I’ve heard it hundreds of times. And what he has done is not okay.

“No.”

In a drumbeat, a denial. There was silence. And then he asked for a favor, to switch a visitation, to have our three boys longer than he is allowed by the courts. I said no. I will not forgive him simply because he demands it. I can possibly forgive him because I have grown to the point where it is better for me to release the pain. But not now, not that day. Not at his request.

His voice changed. He told me if I had sex I would be easier to deal with.

I have read shelves of books and magazine articles extolling the healing qualities of forgiveness, and I wonder. I know it is a popular notion. I know the nation wrestled with the forgiveness of a president. Television talk shows center on themes of forgiveness, bringing out guests begging for redemption for a scorecard of betrayals, hoping to be acknowledged as the audience pleads for a happy ending. I know that atrocities between people are forgiven as easily as coins of red and white striped candy are thrown from a float at a Memorial Day parade.

I know for many an apology embraced is freeing. But apologies are what imprisoned me. I cannot honestly absolve my former husband of the abuse. To say I do would be a lie. He dismisses all he has done as trivial, while the abuse, no longer physical, has transformed to verbal and emotional, playing itself out in bitter phone calls and seemingly endless litigation, with the children as pawns when convenient.

Forgiveness for me means absolution, wiping the slate clean. I cannot do that to a man who I feel deliberately and cyclically abused me. I do not hate him, but I am aware of who he is, and it is not excusable. What he has done to me, and continues to do, cannot be dismissed. Sometimes the only one you can forgive is yourself.

Forgiveness undeserved is what compelled me for one-third of my life, the twelve years spanning the time I was twenty-five years old until just after I turned thirty-seven. Nine years of marriage and three children all added up to a monument to forgiveness. And it was forgiveness that perpetuated the spiral, a forced compassion required to constantly understand and forever swallow explanations that were hollow and unworthy. I was moved further into this quagmire by my own driving desire to make my marriage work, to succeed at all costs, and to cover up the glaring evidence that this model man I married was not at all who he seemed. I see now that forgiving him is what granted the violence permission. Being the forgiving rubber wife is what allowed this to unfold.

Perhaps the word I need for him is not forgiveness but understanding. That may heal me. The anger does wash cleaner as time passes. It does get farther away, lost in the separateness of our lives, the wholeness I feel without him, the fullness of work that I love, and the business of loving my boys. The harsh, jagged edges of my rage at having been so duped and gullible are worn smooth by time and new experiences, but the rage is there, nonetheless. Ubiquitous, but tamed. The passion of my indignation has faded, bleached by the new, honest life I began the day he left.

I know it would be futile to say I will forget. I cannot forget that I was the victim of a hushed, private violence; it is as much a part of me as are my three small boys who shout desperately for my attention from rooms down the hall. To forget would mean to embrace the chance that it may happen again. My memories, aggressive and ravenous as tigers, will not let me forget. I can pray someday I will understand why he did what he did. I am beginning to understand why I accepted the violence, and it has not been simple.

Surviving domestic violence is like walking away from a raging fire that has consumed your home, your life, and your self-definition. You are plagued with the details of how this atrocious fire began, how it spread, and how it took so long for you to jump to safety. Sometimes it just starts with a forgotten match. And before you acknowledge the danger, your life is engulfed in flames.

In June 1997, on my thirty-ninth birthday, I came home from dinner with my friend Mariann, her treat for my birthday. I pulled my gray 1990 Volvo station wagon into my garage, pressed the automatic garage door button, and walked up the back stairs into the kitchen. I paid the baby-sitter for the evening and watched her through the window as she walked to her parents’ car, parked at the front curb. I paused in the kitchen for a glass of ice with water, walked quietly upstairs, and kissed each sleeping boy as he lay in his bed.

Weldon, then eight, was in his room decorated with a sports theme, his favorite Goosebumps books lying on the floor where he had thrown them. Brendan, six, and Colin, three, were asleep in their beds in the room with the bright red farmhouse my sister had made for them. They looked small and peaceful, their blond hair brilliant as moonlight as the hall light shone on them.

I went to my room to put on my nightshirt and get ready for bed. Reliving the laughter Mariann and I had shared, I opened the medicine cabinet in my bathroom, reaching for contact lens solution. The glass and oak cabinet door, one in a triptych, came loose in my hand and fell on me, heavy and blunt, sudden, unprovoked; a thunder hit above the cheekbone and against my chest. My arms strained to keep it from crashing to the ground. I laid it slowly on the floor, against the gray-tiled wall.

Then, the past erupted of its own volition, memories I could not contain, like rubber snakes in a trick cannister.

The panic I knew from years of rehearsals raced through me, triggering that familiar fire drill. Ice. Stop the swelling. Will anyone see? My face roared in pain, my chest throbbed. How will I camouflage it? Is there a cut? How big is the red mark, and is the white epicenter smaller than a dime, bigger than a golf ball? I knew the routine well.

If I get the ice on it right now, this second, I can hold it down, I can fool the skin, I can pretend it never happened. Have I been able to deny a blow this big before? Concealer, blush, the thick matte foundation, maybe powder; the Chanel foundation won’t work, it’s too thin.

Desperately checking the red marks in the mirror, minutes fresh, I moved down the checklist, a path grooved from experience. Fingering the ice cube in a glass of water I had filled just moments before, I placed it cool-stinging on my face, grimacing at the stunning, frigid solution. I can let the chest and arms go for now. I must hide what is on my face.

And so I relived each hurt there that night, remembering who I fooled and where I was, congratulating myself on how clever I was to be such a master of disguise and deceit. This isn’t so bad. He isn’t so bad. If no one sees what he has done, then no one will think he is a monster and I am a fool.

The time in 1986 when he punched me on the chest in Dallas (he was just trying to stop me from walking away,

and his hand accidentally was formed into a fist, he said), I wore high collars. The bruise on my arm from his bite after we had moved to South Bend, Indiana (when he was so angry at the progress of his own therapy he became infantile, the counselor declared), was simple enough to ignore in winter. In 1991, with two boys under two, I saw no one else during the day, filing stories for newspapers by my computer’s modem. Play group with other mothers in the area was only once a week. I was away from my family. No one would see.

Also during our time in South Bend—during his first year of law school in 1990—we flew back to Dallas during his spring break. We attended the wedding of the sister of a close friend. We mingled, eating carefully fashioned hors d’oeuvres from silver platters served by young men wearing white gloves. We danced only hours after he gave me a black eye (the time, you know, when he just momentarily lapsed because we were staying with friends and our son was so young and law school was so stressful). I was quite sure our hosts had overheard, and Weldon, then one, was terrified, crying and clutching me. But no one had asked.

That night, I danced with the priest from Holy Trinity Catholic Church, Father Lou, who had counseled us in the Pre-Cana requirement before our own wedding. Even he did not know the pain filling my brown satin shoes. “Weldon hit me with the toy phone accidentally,” I told him, I told them all. They all believed me. That my handsome, witty, charming, loving husband would act violently was absurd.

No one would believe me. I can’t ruin our vacation. It will be fine. It will never happen again. Ever.

At his family’s Christmas party in 1992, his oldest sister joked about my lip, swollen and blue-black from a blow he gave me December 24, after an argument about the Christmas rituals of our families. “Did he hit you?” She laughed at the insanity of the prospect and went into the kitchen to get me a glass of white wine, with ice. “No, Brendan threw a toy train, aiming for the toy chest, and I was in the way.” This was my practiced response. “He is so strong,” I said. “I bruise easily.”

But just so you know, I wanted to say, your brother did this because Christmas with our families is so tense. “Can you pass the dip? Did you melt the cheese with the salsa or stir it in after? These egg rolls are so good.” Will you still love me if I tell you what your brother has done?

And then there was the aftermath of the last time in 1995—though my husband did not know it was the last—when he came to me in our bed, the bed we had bought for our new home. It was four days after the last assault and two days before the morning in domestic violence court that changed our lives, the morning I stood up and spoke the truth about the man I married. Just before 6 a.m., he was dressed for work in one of the white shirts (medium-starch, boxed please) that I picked up at the cleaners dutifully every week.

He sat near me on the bed as I laid there, not having slept much or well, dreading another day with him in our house. He said impatiently, “Just write an apology for me. Anything you want me to say, and I will sign it.” He refused to be the architect of his own contrition. I didn’t do it, of course, but the wisdom of that choice often strikes me—in court mostly—that it would have been a great document for the file.

Only seconds had passed since the cabinet fell, but each memory was vivid and searing, demanding to be acknowledged as if it had happened just now, just then. And then I remembered where I was. It was my birthday, and he was gone. He had been gone for almost two years. Exhausted, I stopped reciting the excuses and reliving the fallout, the cover-up, and the victory of concealment.

There was no need to keep throwing the dice with a memory of another injury, long healed. This time it was innocent, an accident. The medicine cabinet fell. No one was to blame. He did not hit me this time. He was gone.

I cried loud and strong, the tears dropping fast and full on the floor, my voice making a sound of anguish so powerfully hoarse and deep it didn’t feel as if it came from me. I thought that after he left our home and our daily lives, I would never be forced to walk through the checklist again, grabbing for ice, wondering who would see and whether they would know. I hadn’t planned to ever feel this hurt again.

I sat on my bed, the same bed we bought together, but now in a new house and covered in all white: a new white duvet cover, all-white pillows, even a white canopy. I was claiming purity for myself, though I could no longer claim innocence.

So the boys wouldn’t hear or be afraid, I closed my door and I kept crying. I cried for all the nights when I came into a room singing, only to leave hours later performing a triage dance of camouflage, spreading leaves and branches over a dark hole so no one would know it was there. I cried for all the women I met at the battered women’s shelter, Sarah’s Inn, where in our weekly group sessions, we shared the stories of men who seemed to be the same person. I cried that I had needed to take my children to a sanctuary for battered women, for help, for relief, to understand, to heal. I cried for the women on this Saturday night rushing for ice, hurrying themselves through their own checklists.

I was one of them, they were part of me: a sorority of good, kind, smart, trusting women who loved men whobused them. I cried that I knew a quick way to hide a black eye and that I had once thought love meant forgiveness was mandatory and unconditional, as it is with children.

My shoulders pulsed up and down as my insides released a howling, jailed horror. And then I knew that this hurt I was feeling would always be there, making itself known in the cabinets that fall innocently or the balls and toys the children throw that land here and there and hurt nonetheless.

I realized I was still wounded, like a soldier, and that loud noises or the sudden bruises recalled the gunshots and the grenades. They unleashed the wild dogs inside me who guarded my long-strangled secret. When I could breathe smooth and slow again and my chest didn’t feel as if it would collapse from the weight of my memories, my tears stopped. I could be calm.

The honest answer to his plea for forgiveness, right now at least, must be no. But one day I may look inside and find the anger has burned away to ashes. I will live better, love honestly, learn well from the madness.

“I’m sorry, you know,” he said brusquely once as he dropped off Brendan after an afternoon visitation. He had been gone from the house a few months. He was ordered by the court to stay outside; he came in the house anyway.

I was not able to acquiesce on demand. “It’s not okay. It’s not enough. Are you sorry for hitting me? Are you sorry for ruining our lives? Exactly which part are you sorry for?” My hands were shaking.

“I’m sorry for it all,” he said smugly, as if all he had done was spill a cup of coffee on a white carpet or track mud on the kitchen floor. He was smiling.

I didn’t buy it then; I had grown immune to his apologies because they were followed, always, by new aggression, in whatever form it took. He would retreat in his attacks for weeks, sometimes months, then reappear, unprovoked, with new hostility, another fight, another battle, another twist of truth.

I may eventually forgive him. I am not there yet.

But I do forgive myself.

Forgiving myself for staying with a man who abused me has not been an easy act, an automatic assumption. It has taken every moment of the years since July 7, 1995, when the man I married left our home for the last time under an emergency order of protection. I have had to work hard to convince myself it was all right to stay as long as I did, that I did what I needed to do at the time. I had tried to make it better.

I was vulnerable, naive, blinded. I believed in a man I loved, and I did not believe he would keep hurting me. I stayed with him, and I chose not to see the man I married, the father of my three children, as a batterer who would always be a batterer. I saw each instance as an isolated nightmare, all explained away, all forgiven. I didn’t connect them to see the pattern.

I excused his rage because I could not bear seeing him as he really was. That meant I would see myself as I was, and I refused to be a battered wife. But it was not until I could make that admission that the abuse could possibly end. It was not until I could say out loud what he had done that the carousel of pain would stop, and I could get off the painted horse and walk away.

Now I forgive myself for staying. I try to forgive myself for choosing for my sons a father who battered their mother, though that has been the most difficult. I forgive myself for trying so hard, for believing in something impossible, for having hope. I forgive myself for pretending to be happily married and pretending that a man who abused me just didn’t know how to handle the demons inside him. I forgive myself all the excuses.

I can forgive myself because the game is over and he is gone. I saved myself, and I saved my sons. With only his occasional appearance, we are happy and whole, a family. I forgive myself because I can now fill my children’s lives with new memories and laughter that I pray sustains them. These new memories include ones of a mother who is strong, a mother who loves them beyond measure, a mother who taught them that forgiveness is earned. I taught them, by what I have done, that sometimes you have to leave.

I taught them that it is never all right to hurt anyone; it is wrong to impose your strength on anyone else. I taught them and myself that it is foolish to think you can change another person’s behavior, no matter how hard you try. I taught them to love with kindness, not control.

Forgiveness is a choice, always a choice. It is not a forced requirement.

Yes, I forgive myself, and writing this book has initiated the process. In speaking the unspeakable, in writing and witnessing the truth, the power of the secret is diminshed. I no longer carry the ghosts of domestic violence with me in every conversation, every act, every movement. I don’t feel that I wear a scarlet letter V for violence.

I can be someone more than a once-battered wife. I have exorcised the terror of spousal abuse by writing it down. Jarring memories reclaim me at times of their own volition, and I know they are there. I respect them and the lessons they have taught me. I acknowledge their power. I am thankful sometimes for those memories because they keep me humble and remind me to be sensitive. On paper now, it seems so clear. It never did when I was living it. My eyes are open. I will not close them again, look away, or deny what is right in front of me. I am conscious. I will not distill the truth and spin it so it no longer shames me. No longer crippled by my wish for a happily ever after or deluded by my self-deceit, I see what is there.

I have won because I have won myself back.

I claim me.