Читать книгу I Closed My Eyes - Michele Weldon - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

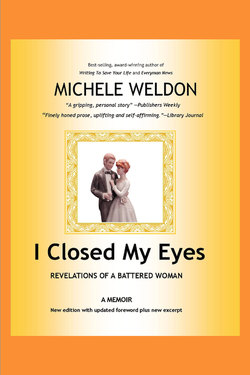

I Closed My Eyes

ОглавлениеI closed my eyes.

Because I knew what was coming.

It was always the same: the air just before thick with rage, red-ripe with anger. I never watched when his hand flew toward me; I only waited for the sound of the strike—shoulders clenched, neck tight—as if all I was waiting for was a balloon popping or the brief, shrill cry when a child falls from a bike, outstretched hands scraping cement.

And when it came, I never knew where his hand went first, which way his fingers grasped me, which arm sent me to the floor. I could never answer the questions properly, the ones that I asked myself, only myself. I could only feel the throbbing and the stings, like battery-powered flashes across my face, sometimes my chest, an arm, a shoulder. And I mentally mapped the argument in bruises and splits of skin, the blood warm and wet, my cheeks puffing up to apologize like air bags upon collision, the truth suffocating within me.

In twelve years together, including nine years of marriage, there were repeated split-second eternities when the man who was my husband was someone I didn’t know. And in those crimson flashes before each time he struck, I always remembered his eyes before I closed my own. Cold blue, pale as stone, the pupils wide, black chasms, his dark eyebrow arrows aimed at my face, his teeth gripped hard to his mission.

And before I closed my eyes, I held my breath, knowing that sanity does not hold court here. With my own eyes closed, the image of his eyes stayed before me in the darkness, like the square image of a television screen or the fading imprint of a lamp’s white-hot bulb across the inside of your eyelids when you first surrender to sleep. In my darkness, I was swimming underwater, without sound and without weight, body-less, soul-less, lost, unable to breathe or speak or remember.

As soon as the sound came, I felt a relief in the distant place where he struck, for there was no more need to recoil, only recover. This was the end, not the beginning of it all. There was no more reason to be afraid. Today. Ever. This has to be the last. This can’t happen again. The stinging radiating through my body reminded me that all I had to do now was heal. A different movie was playing, a slower soundtrack, with a woman’s soothing voice.

I would cry without sound at first, the hole inside me so vacuous, so unforgivably hollow that the loudest knell could not penetrate its emptiness. I was already beyond it; I had flown past and above and could no longer be touched.

You didn’t get me. My eyes were closed. It didn’t count.

I closed my eyes, yes, I always closed my eyes. I didn’t want to see him smiling. I didn’t want to see what he promised he would never do again. And with my eyes safely closed, I could escape to the mountains inside me, the paradise he couldn’t poison or devour with his words. I would find again the haven where I kept the kaleidoscope of colored drawings, where I could hear the songs inside me sing again, the tears heralding their own chorus of comfort. Inside me, I could feel the heaving breath of my children sleeping, soft as puppies.

I couldn’t hear him, really; the sounds about him were muffled and strange, animal-like, sometimes cursing, sometimes whimpering, never quiet or calm. I could not attend to him for I was somewhere else, always, somewhere he could no longer touch me. The apologies would come later; they needed time to warm up.

The man with the cold blue eyes and the percolating apologies was not the same to anyone else in the world. He was a different man. Completely.

Handsome and convincing, he had once looked charming and regal in the navy blue Bigsby & Kruthers suit my mother had bought him to celebrate his graduation, cum laude, from law school in 1992. He was a litigating attorney in one of Chicago’s largest firms, Sunday school teacher, mentor, all-around great guy, the kind of guy other fathers called to play handball, the kind of man who was just a little too intense in a Saturday game of basketball. He cheered at my oldest son’s T-ball games and carried the children in the rain under umbrellas on Halloween, ringing all the doorbells. He called my mother on Mother’s Day. He smiled in all the pictures and sent me flowers in colors so brilliant they eclipsed the bruises on my arms. He wrote me beautiful letters.

“Your husband is so wonderful,” cooed more than one woman friend—envious and ignorant, part of the throng who knew us from church or work or the neighborhood—from across the social distance you keep when you want a secret hidden. “You are the perfect couple,” I heard often. “You have it all.”

He was even a good dancer.

Athletic, articulate, intelligent, funny—he seemed to be the perfect husband, the perfect father. I watched other women flirt with him, some innocently, and each time I thought, If only you knew. He delivered passionate soliloquies at parties about how proud he was of my career as a journalist, my accomplishments, my love for our boys, my ability to keep all the pins in the air. But behind the curtains, away from the crowd, I was juggling barefoot on shards of glass, spinning, tiptoeing past him, around him, to keep intact the wounds that would spill our family secret, hoping no one else would see.

If they find out, it’s over.

“You talked too fast,” he whispered in my ear once as I sat down at a starched white-linen table. I had just delivered a speech at the annual fund-raiser for Tuesday’s Child, a nonprofit intervention program for children and their families, where I was on the board of directors. The hotel ballroom was moving with applause and cheers. I drank in the approval and absorbed the nods and smiles sponge-quick, eager to be liked, eager to be loved. He had to criticize.

They like me. You’re wrong. Could I be married to one of the smiles instead?

“Psycho wife,” he would sing to himself in the kitchen loud enough so I would hear. “Loser,” he would call to me to underline a thought. And sometimes the taunts lasted until the moment the car, filled with our friends, honked in front of the house, beckoning us on a Saturday night. I wiped my tears as he walked brusquely past, pushing my hand aside as I tried to reconcile.

And then, only hours later—sometimes less—he could smile and lift a glass of blood red wine in a toast to tell all the world how much he loved me. And I prayed that this public face would become the face he wore at home.

Maybe if we stay out all night. Maybe, this time, he won’t change back.

Because whoever this man was in private was someone I did not want in our house. Without him, his stress, his excuses, our house was filled with joy and promise for me, filled with the laughter of my women friends and our children. Our house was a mosaic of bold colors, flowers, and pillows I covered in silk and tied with ribbons, photographs of smiles, the picture of a happy family growing, the face of love, completeness.

In the kitchen the refrigerator was covered in crayoned pictures, and in the family room, toy boxes spilled bad guys and trucks. On the table in the breakfast room a bowl was filled with apples the color of love.

But with him it was often a completely different address, a scary place where my stomach tightened and my head pounded, hammering behind my eyes, hammering them shut. When the boys went to sleep, I did not feel safe.

He’s dangerous. Get away from him.

I felt he brought the violence with him, his rage so palpable at times, it had its own seat at the dinner table. It took all my energy to avoid it and to pretend it could stay hidden. It was the monster under the bed, the bogeyman in the closet. His rage was the reason, in the last few months before he left, that I reached for the asthma inhaler when I heard his footsteps on the back stairs, the reason my hands shook at times when he called on the phone from work, the reason I rarely complained when he worked early and late, weekends and holidays. It was the reason I slept soundly only when he was away.

But I stayed. Married, committed for better or worse, and it was worse than anyone would ever suspect, worse than I would ever admit. Each day the violence, for years even just the memory of violence, eroded more and more of me.

I dreamed I didn’t have a face, Mom. You gave me a small bag of bright fuchsia lipsticks, black and shiny in their containers, five in all. “Here, you love this color, dear.” And I couldn’t use them, Mom, because I didn’t have a face. Where is my face? Did he hit it away?

I thought the proper response was to endure, to be a good Catholic wife, to help him through it, over it, under it, wherever the hell he needed to go to get away from it. I told myself I should stay to fix it for him, for the children, lastly for me. I would stay so I wouldn’t be alone, so there could be a happy ending, so I could stop gripping the edge of the bed and praying he wouldn’t touch me. Where were the sincere promises, the soul-baring letters, the words imploring me to love him, the eyes that asked forgiveness? How could it have come to this from such a happy beginning?

I prayed the terror would vanish as quickly as it came.

I chose him, at first, because he seemed safe. He was from a good Irish Catholic family. We were in the same high school class at Oak Park–River Forest High School. He graduated from a Catholic university, majoring in philosophy and literature, Great Books they called it. After a year in the seminary, he decided to be a writer instead. For God’s sake, he almost became a priest.

He was a man with promise, a man filled with dreams I wanted to share. He was witty, captivating, smart, and strikingly handsome. He didn’t smoke, drink, gamble, or do drugs; he wasn’t even rude to strangers. He loved his sisters. He hugged his mother hello. He could admit his faults, and he was always so sorry.

When we started dating in October 1983, I was not looking to be saved, rescued, delivered. I was looking to love and be loved, have a partner, share a life, build a family. I had known him in high school and saw him again eight years after we graduated, on State Street. I was walking home from work, and he was walking to his late-shift job at a news service. I handed him a card with my home phone number.

Before our third date he said he loved me, on the phone from his office. I wanted the kind of deep, passionate love he professed. I was flattered he couldn’t live without me. Of course I deserve all this attention. Of course he fell in love with me right away. He was infatuated, adoring. I am this wonderful, so he must be too. Isn’t everyone young and in love deserving of it all? Isn’t it always this simple?

For the three years before we were married, he was a man whose life seemed ruled by his love for me. I relished it and loved him back.

So I forgave the violence when it arrived, unannounced and without warning, three years after we started dating, shortly after we were married. I treated it as if it were only a minor transgression, like forgetting to take out the garbage or coming home long after dinner was put away in Tupperware bins. I forgave him because I didn’t want it to be true. I only knew about violent men from television, movies, or an occasional talk show. The man I married couldn’t be like them. That was impossible.

The first time he hit me was on New Year’s Eve, 1986, four months after our wedding, when the world was silver-and-crystal perfect, and we danced to Lionel Ritchie songs and toasted to forever. I don’t remember why we fought; perhaps the wine cost too much at dinner. I remember where we were—in the second bedroom of our duplex on Oram Street in Dallas. I remember he was wearing a brown suit, and I was wearing a black skirt, white silk top, black satin shoes; I remember looking at my shoes. I remember his eyes as he pushed me on the chest, his hand outstretched and hard, forcing me down as I lost my breath, lost my balance, and lost my trust. He had never hit me before. Afterward his eyes were full of tears. I wore turtlenecks to hide the bruises.

I’ll do everything perfectly. I’ll make my life full. He won’t have to do anything. We can be happy.

Of course I accepted that I contributed to the argument, he made sure of that. Of course he was a good man who lost his temper. Of course we worked to break the pattern. I put all the flowers he sent in the living room. We took walks, we made love, we went to a marriage counselor. But it was never good for long, and it was never good enough.

He hit me again. And again.

It started sometimes as a slap, a sudden sharp-dagger movement, hitting my mouth, my eye, my nose, an arm. It could have been an argument over bills, a party, a misunderstanding, the boys. Sometimes he didn’t hit me; he only raged. Once he mangled a blue wicker hamper because I cleaned the kitchen floor while he was reading the newspaper. The arguments always ended as quickly as they began. One strike. One hit. It was over. He would run away.

The counselors—three in three different states—each spoke in soft, generic tones, sometimes for $90 for fifty minutes and sometimes in rooms so small I wanted to vomit. There was Anne-Marie in Dallas in a pristine office in a stark boxy building with a tape recorder. In South Bend, there was Mickey, a university counselor, handsome and athletic, just like my husband. In Chicago, there was Father Gerry, the kind pastor who had known my husband’s family his whole life. In each office, I stirred my coffee or bitter tea in a white foam cup and couldn’t look at my husband playing the melody of deceit with his church voice. And each counselor said to contain the anger, be kind, be careful, tell each other you love one another. Be sorry. “Say the word suitcase,” Mickey said, “when you feel as if you are about to blow. Have passwords.”

After each time, we went to a counselor, and he sent more flowers, enough blooms to fill a cemetery. He let me sleep late on Saturday, made dinner a few times a year, changed the oil in the cars every few months. He brought me blouses from Ann Taylor and wrote me long letters. He put a patio in the backyard. He made new screens for all the windows in the house. He called our boys gifts from God. He recounted the moments when each child was conceived. He said he believed in me, and he said I was good.

I am not a battered wife.

But it began to occur to me, in the urgings from a small voice deep inside that I could not silence or avoid, that the good man with the bad temper was just a bad choice.

He has to know that what he is doing is wrong. He is logical, intelligent. It is stress. It is his own fury. It isn’t me. He only hits me once in a while. I cannot only bear it, I can change it. I did not cause it, but I can solve it. I can make this man be who he says he is, be who I need him to be. I will make it all better. No one has to know.

So I would not tell. I knew that my close friends and my sisters would tell me to leave—no, make me leave. My friend Ellen knew the smallest part of the puzzle and wondered why I stayed, as she wondered why the whole family—even Colin—bristled when the garage door went up and Daddy was home. “Why are you still married to him?” my friend Dana asked.

I was afraid my brothers would hurt him back and my mother would pack our things and drive us away, with my boys screaming for their father. I was afraid of someone, anyone, seeing what really happened at our home.

What did you do to make him mad?

What would I say? Wasn’t he the handsome lawyer? What was wrong with me? Wasn’t I able to keep the family safe? I was ashamed to let anyone know what was happening to me.

I am not a battered wife.

I hated that I forgave him, that I was seduced by his explanations, his reasoning that his love was so vigorous it defied boundaries. “No one has ever loved you like this,” he said, not knowing how true it was.

“I am a beautiful woman, and look what you have done to my face,” I cried once.

“I am sorry your self-esteem is hurt,” he shrugged, as if all he had done was drop a bottle of my makeup on the bathroom floor.

I hated that I forgave him—such a weak, chameleon move—like those weeping, pleading women in the country western songs, the lead roles in made-for-TV movies. Even months after each episode, when the apologies no longer hung between us like clouds, I could never answer the why. So I stopped asking it out loud. And in the weeks and months that swelled to fill the voids between the violence, what was real became blurred. It was just a blip on a time line once the bruises had bloomed past yellow and the blood had been bleached from my nightgowns.

I am not a battered wife.

“Pack your bags. Gather your children,” I was told. “Violent men never change,” the voice on the shelter hot line said. “Have an escape plan,” the counselor in South Bend told me.

Get out. Your children are not safe. Do not stay.

But I did, and we went on to have three children, anniversary dinners, family picnics, and New Year’s Day parties. And in these cramped parking spaces of hope and laughter, there was temporary shelter for my fears, the terror slipcovered neatly in promises. And he thought I forgot. But if I told my story to no one else, I told it to myself a thousand times.

With time, the unspeakable was no longer spoken of. I wondered sometimes if this handsome man—with our youngest, Colin, on the back of his bicycle in a baby seat, waving to the neighbors—was really the bogeyman I feared. I wondered sometimes if it all had ever really happened. If my eyes were closed, was I only sleeping? Did I remember it wrong?

“What happened in Dallas will never happen again,” he told me as I folded the laundry in the basement just four days before the final blow. Which time in Dallas? The black eye? The bruised chest? The slap? I dared not ask. He seemed contrite.

But there were forever the black eyes and the fat lips to halt me, to distort the dream, to remind me this man was not at all safe. “A man hits you in the face,” a police officer told me later, “because he knows you won’t tell a soul.” And I didn’t.

Opening the presents on Christmas morning, 1992, the videotape shows my swollen lip. Is this all you gave me for Christmas?

There was the punch when I was five months pregnant with our first son in 1988. I locked myself in the small bathroom with the mint green towels, and I stripped off my clothes to take a bath. I saw myself swollen, my belly bursting with the child I craved. My image shook in the clouded mirror.

What am I supposed to do now?

I didn’t leave then, compelled by loyalty and the belief that he did not mean it, propelled by the encouragement of Anne-Marie—who said we could stop the violence by being kind and by discussing the roots of the anger, as if any of it was my choice. I tried to believe, wrestling with rationality, suspending my fears that this man I loved was not married to rage.

I believed in him far beyond what was real, what was called for. I told myself he was not a violent man.

I can’t be that stupid. I am not a battered wife.

I pictured the violence like a cloak, a shroud really, jet black, thick, consuming. I imagined it was something he could choose to wear (like the red tie instead of the blue one, or the brown shoes instead of the black) or choose to keep hidden in the closet forever. I pictured the violence as outside of him, as outside of us, instead of at his very core, welded to him, inseparable from him, a part that was immutable and not in my control. I should have known that a man who hits me once will always hit me. I should not have let my dreams overcome me. But when your life is covered in fog, you cannot see the exit signs.

And when your eyes are closed, you see nothing at all.

As the years wore on and hope became more forced, I kept loving him out of habit, out of loyalty, trying to keep the hurt at bay. I kept up the game, bringing the boys downtown to meet him for dinner, having his parents and family to the house for brunches, throwing parties for the law review staff where he was editor-in-chief, hearing his opening arguments in court, buying his secretaries Christmas presents. All the time, I kept my fingers crossed, hoping that he really was a man like my father, that he was gentle and that he loved me no matter what. I hoped that these instances of violence were aberrations, that he would change back for good, that each time was the last.

But there comes a time to stop pretending.

The soul, I have learned, has its own agenda and knows the truth even if you dare not acknowledge it. When the slaps, bites, and punches are long since anesthetized in afterthought, there comes a moment when, of its own volition, your soul says, “No more.” You may not even hear it shout, or simply nod to its defiance, but it is there. And from that voice comes the solution and the strength, the voice no longer mute, the voice so clear it is deafening in its resolution.

There is a last time. And though it begins the same, the end is different.

At 10 p.m. on July 1, 1995, I walked behind my husband to the back bedroom of his parents’ Wisconsin summer house to go to sleep. I had earlier placed Colin, who was one, in the crib in his parents’ room. Brendan and Weldon were sleeping in the third bedroom facing the road. We argued. I told him I was angry he had made demeaning sexual comments about me to his brothers earlier that day. He wanted to leave to go to a local bar with his brothers and his old friends; I wanted him to stay to resolve the conflict. I wanted him to say he was sorry. In a half hour, we argued for what felt like forever.

“You hate me! Say you hate me!” he screamed, his teeth clenched. He leapt up from the bed where he was sitting as I stood above him, holding baby wipes in one hand and diapers in the other.

Lightning fast the air closed in between us. As always, I closed my eyes. Fingers cold and stiff as steel grabbed my jaw, and my mouth was struck before I landed headfirst against a wall. It happened in slow-motion darkness, like a B movie on pause in the vcr while the children slept; his mother watched a Dorothy Malone movie in the living room, and his father dozed on the front porch during the news.

The last time is different. After days and months and years of bandaging the violence, it suddenly failed to matter why. It was time to get away. It was as if someone else trapped inside of me long ago demanded to be set free.

I screamed.

In the black pool governed by my blindness, my eyes closed still, I was whole in the resolve that in spite of the confessions and promises no doubt to come, a resilience inside me was growing so cancer-fast that I knew it was over. And as I lay there on the cool white tile floor—blood filling my mouth, my jaw aching beyond movement, my head reeling—a part of me was joyful. I will never do this again. I will never again be a battered wife.

Footsteps came down the hall.

I will tell. It was, after all, time to open my eyes.