Читать книгу The Mountain Knows No Expert - Mike Nash - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Young Man Blossoms

Chapter 3

When George Evanoff was about thirteen years old, he went to work part-time in the butcher’s shop in Edson. His brother, John, recalled that George worked because he wanted spending money: “There wasn’t much money in those days; Dad was just a section hand, a car man; he didn’t make that much money — there were four kids, and he had to raise a family. Mum didn’t work; although of course she did, she worked hard in the home.”

John remembered that George’s first job was to deliver meat on his bike: “I think that was the first bike that George had. He had to buy it, and he had a big carrier on the front, and another big carrier on the back. We would load it up and wheel it around town delivering the meat — in the winter it was a little difficult with the snow. George did that for a couple of years, after school and all day Saturday. He probably started doing some butchering after a while.”

Despite their new responsibilities, John noted that he and George still made time for outdoor activities, especially on Sundays: “That’s when we went out in the bush, we and our neighbours, the Kutyns. On Sunday mornings when they went to Mass, we would wait until eleven o’ clock before we could do anything.” John added that he and George never went to church at all, even though most families were religious at that time. (George Evanoff’s evident spirituality later in life is discussed in the Epilogue.)

Anyone who hiked with George Evanoff in later years quickly realized that, for a man of apparent average build, he could out-walk almost anyone. Apart from his obvious fitness and determination in the outdoors, he had a physical advantage that wasn’t obvious at first glance — a short torso and long legs. John remembered this from when they were kids: “George had long legs, same build as Bob — we used to go fishing and take the canoe. I would be quite small, and they would be running; George never walked. There were the two of them, and I’m in the middle, hanging on for dear life as they’re running through the muskeg.”

John shared more memories from their youth:

We had a good childhood. We never had much in the way of material goods because the money just wasn’t there, but we always had enough to eat, and fresh warm clothes in the winter out of the Eaton’s catalogue. Every fall, Dad would measure us and would go out and visit the local Indians and trappers and there would be fresh moccasins every year. We always loved running through the bush in them. And the gauntlets — beaded and made by the local Indians, from whom Dad used to buy furs. He would load the car up on Friday night, and put the axe, saw, and chains in, and quite often he would have to build his own road to get out there. He would visit the trappers and would come back with his car loaded with wolf, fox, and coyote pelts. We would have loved to go with him, but this was business. He was selling to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and to another buyer in Vancouver, and he would go away on selling trips from time to time. George and Luby would also go on the train to sell the furs; Luby was more or less in charge, and George was there to protect them. George would be sixteen or seventeen at the time.

Along with his early entrepreneurial bent, George also had a strong sense of fair play that led him to organize some youthful protests in Edson. One of these occurred as a result of a price increase for chocolate bars after the war. Mary explained: “Chocolate bars had gone from five to eight cents, and George was one of the leaders of the protest in Edson. As a result, all the stores put the price down to five cents. It lasted two days — we had a two-day victory.” It was the spring of 1947, and chocolate companies had boosted the price of chocolate bars, claiming that production had dropped because of a disease afflicting cocoa beans on the west coast of Africa, increased demand from post-war Europe, and the removal of American import controls. All had combined to trigger a large price increase overnight. But Canadian kids weren’t buying it, and the famous chocolate-bar war quickly spread across Canada, ending only after a Toronto newspaper suggested that Communists had fooled Canadian kids into organizing the protest.1

Introduction to the Mountains

George’s introduction to the mountains came when he and John were still young. John recalls that they did quite a bit of hiking in the mountains when they were kids: “I remember one summer when we took the train from Edson to Jasper, and took the bus to Miette Hot Springs. My cousin, Bob, and another guy rode their bikes from Edson.” Later, when Marmot Basin opened in Jasper, George went there to race.

The person who played a pivotal role in introducing George to skiing in the mountains was Norman Willmore, the member of the legislative assembly for Edson-Jasper. John remembered him:

Willmore had the clothing store right across from the butcher’s shop where George had a job. And there was another fellow, I think he was a schoolteacher; they were avid skiers and they used to take the kids skiing. I went with him once; we drove up to Marmot Basin, back in 1948. We got to Jasper on gravel road in the winter … with Norman Willmore and the schoolteacher. Marmot Basin ski hill wasn’t developed then, but there was a snow cat, and it was four to six miles up to around treeline, where there was a chalet consisting of an unheated Quonset hut. From there we climbed; all we had were wooden skis with cable bindings that you tightened. We had no climbing skins; we just put a scarf or a rope on the skis — whatever we had — and we wound it around the skis. The snow was so deep; nothing was packed; it was just pure powder; and we would climb up and ski down.2 We made two or three runs in a day, if that many, and at the end of the day we skied out about six miles through a cut in the trees. Norman Willmore used to take the kids up regularly. George went often to Whistlers in Jasper;3 they would take the train up — it was only a three- or four-hour ride.

Lillian recalled that the Whistlers, later the site of the famous gondola ride, once had a rope tow. George had told his own children how they used to ski race there, and how one time he couldn’t stop, and went over a bank and ended up on somebody’s car. Looking at a picture of three people at a ski race in Jasper, John picked out his brother as the good-looking one with the trophy. John explained: “He is wearing a uniform shoulder patch that could be the Edson ski club, and he looks pretty spiffy,” adding that he always did.

Edson School Reunion

It was the Canada Day weekend in 2000, and I was driving from Prince George to Edmonton. En route I made a planned stop in Edson to see what I could find of George Evanoff’s roots. In the twenty-two years since I moved to Prince George, this was only my second drive through Edson, and so it was by a remarkable providence that the July 1, 2000, weekend coincided with a high school reunion. By that time, the population of Edson was about 7,400 — four times the size of the Edson of George’s youth, but still very much a small town.

Located over halfway from Edmonton to Jasper on the Yellowhead Highway, Edson’s economy today is based mainly on oil, gas, coal, and timber. It has a long airport runway, which was a factor in Edson’s emergence as the local centre for oil and gas development over the rival town of Hinton, located eighty-five kilometres to the west. The city emblem shows distinctive snow-capped mountains with forests and a river, and in the foreground is a two-lane highway, fronted by a tree — this imagery sums up aspects of George Evanoff’s life.

First I drove out to the Willmore Municipal Park on the McLeod River, southwest of town. I walked around the park, talked with the caretaker, and looked at George’s first ski hill, now used for tobogganing. I bushwhacked along the McLeod River, and saw the rapids that George and Bob had nearly drowned in. After lunch, I drove into town and parked near the red-brick school. This imposing three-storey structure was built in 1913, only two years after the town of Edson was incorporated. It was Edson’s only school until the mid-1940s, and was the one that George Evanoff attended until grade nine. The building was used as an elementary school until 1967, after which it was used by the school district for maintenance and busing purposes. The Edson Cultural Heritage Organization took it over in 1984, and began the lengthy process of renovation to create the Edson Red Brick Community Arts Centre and Museum.

As I first walked around the outside of the building, I saw a large structure set on spacious grounds. Inside, I found George’s old classroom, still looking pretty much as it had in his day, with decades-old sturdy wooden furniture. In the grade twelve graduating class yearbook for 1950, there was a photograph of the Teen Club executive, which included tall, teenaged George Evanoff, the treasurer, and an accompanying biographical rhyme:

He taps his pencil, the girls complain,

Say he’s driving them insane,

Keeps Teen Club finances straight,

Skiing, bowling, fill his slate.

Earlier yearbook entries for George Evanoff provided by Paul Kindiak and Lillian Evanoff reveal his nickname, “Pork” or “Porky,” an antonym, no doubt, for his trim build. It is noteworthy that at only sixteen years of age, George already had his sights set on his eventual career path:

Grade ten (1948) Name: George Evanoff Nickname: Pork Chief Interest: Rods and Reels Chief Dislike: Dancing (oh, those fast ones) Weakness: The opposite sex Favourite Saying: ‘Don’t be nuts’ Ambition: Electrical Engineer

George Evanoff’s official Government of Alberta high school transcript for 1947 to 1950, showed that he was an overall A student. Except for a C in social studies, all of his grades were either As or Bs. Not surprisingly, in light of his later path through life, he earned As for physical education, math, sciences, and business.

New Horizons

As George Evanoff matured as a teenager, he was no longer satisfied with the activities that were available in Edson. According to his son, Craig, George “could see the mountains on the eastern boundary of Jasper National Park, and was drawn to higher places.” From Edson, George started making trips on the train out to Jasper to go skiing, and then he worked in Jasper in the summer. When he was sixteen or seventeen years of age, he also worked on the road to Marmot Basin as a blasting assistant, pounding dynamite into drill holes.

Lillian Evanoff recalled that George enjoyed his summer jobs in Jasper:

He spent many summers working there, and was even in jail for one night. He had a free pass on the Canadian National Railway (CNR) because his dad worked for the CNR. So he and his friend took the train to Jasper, but they had no money, and since it was easy to get work the next day, they slept in the park under a bush. A policeman came by and told them, “You can’t sleep here.” They answered, “But we have no money.” So he took the two young kids and put them in the jail. The next day they got a job. These were George’s growing up years.

Times have changed; it was so easy to get work then, all they had to do was hop on the train with a free pass and the next day they got a job. Young workers had facilities in the Jasper Lodge, where they played tennis and went to the parties. George worked there for the railroad one summer; they would travel around and do the repairs, and they would live in the bunk cars on the train. During another summer, he worked for the Interprovincial Pipeline near Jasper.

Chicago and Toronto

After George graduated from high school, his younger brother took over his part-time butcher job at the local meat market. George got a job in an electrical shop in Edson, which was soon followed by a position in refrigeration with an Edson plumber. These work opportunities likely spurred him to take his first steps towards his eventual profession.

In 1950, George left Edson and travelled to Chicago to learn about refrigeration. He was there for between eight months and a year, and lived with his mother’s uncle. John Evanoff recalls that they had a lot of relatives in Chicago on their mother’s side. He enrolled in the Greer Shop Training School from March to June 1951, and earned a diploma in refrigeration. While in Chicago, George went to a lot of big-name musicals in his free time, and developed an appreciation of music, including classical, that lasted throughout his life.

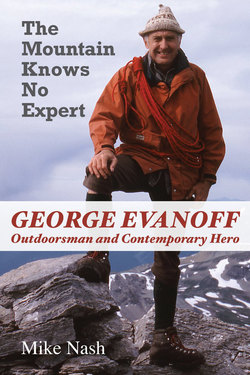

Portrait of George Evanoff soon after his graduation in 1951.

Although he did not have a work visa in Chicago, George managed to get work in a butcher’s shop or fish market to help support himself. But the immigration department was soon after him, and he had to quit his job and leave the city. With his diploma from Greer in hand, he went to Toronto, where he worked in refrigeration for a little over a year. Little information is available about this period in George’s life, since he was away from the friends and relatives that lived in his hometown, and he had not yet met his future wife. It is known that George skied at Collingwood and other Ontario hills, as he later compared them with the dry-powder skiing that he relished in western Canada.

George did have one celebrated misadventure while working in Toronto. While making a delivery using the company service vehicle, George tried to take a shortcut by doing a U-turn. He accidentally took out all the boards in a picket fence. George, who was only nineteen years old, tried to make a run for it, but the owner caught him, and George had to make it right by paying for the materials and doing the work to rebuild the fence. There is one other tantalizing clue to George’s life in Toronto. His future wife, Lillian, notes that George must have partied in Toronto because “he came back with quite a wardrobe.”

Return to Edmonton

George’s parents moved to Edmonton in 1952, the same year George returned to Alberta. George switched careers after settling in Edmonton, and undertook a four-year electrical apprenticeship from 1952 to 1957 with Hume and Rumble, a major western Canadian electrical contractor for industry. George went to Calgary for 240 hours of courses each winter during the months of January and February at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. In the summers, he worked mostly on pipelines, installing industrial electrical equipment, and designing controls for new pumping stations. His electrical apprenticeship was entirely separate from the refrigeration work that he had done earlier, although undoubtedly that experience benefitted him. He had completed half of his apprenticeship with Hume and Rumble when he met Lillian on a blind date in Edmonton in October 1954. It was on Sadie Hawkins Day, an occasion popularized by Al Capp’s Li’l Abner cartoon two decades earlier, during which the girls ask the guys out. On this occasion, George and Lillian’s mutual friends arranged the dinner that they attended. George made an immediate impression on Lillian, who observed many years later that he was “a big city dresser.”

Marriage

Lillian Minailo was raised in a Ukrainian family in Wasel, a small farming community on the North Saskatchewan River about ninety kilometres northeast of Edmonton.4 Lillian’s parents had a mixed farm in Wasel, and Lillian was the second youngest of seven children, with two brothers and four sisters. As a child, Lillian loved to go outdoors, and from an early age she had a feeling for nature.

Apart from the usual movies, parties, and dancing, she also used to go out walking with George during their courtship. George and Lillian saw a lot of each other after that, or as Lillian put it, “George was at my doorstep all the time.” They were engaged after a few months, on George’s birthday, March 19, 1955, and were married less than five months later at St. John’s Ukrainian-Greek Orthodox Church in Edmonton on August 5, 1955.

George and Lillian’s wedding on August 5, 1955.

George’s younger sister, Mary, was engaged just before George, and she recalled that he had approached her fiancé to ask how he had proposed: “We didn’t realize what he had in mind until a week later, when he proposed to Lil; and then they were married a week after us.”

Tumult of Early Domestic Life

After his marriage, George still had two years to complete on his apprenticeship. He graduated as an electrician in 1957, shortly before his first child, Delia, was born. His final progress report from the Alberta Provincial Apprenticeship Board, dated April 1957 showed a 100 percent attendance record, a school rating of 92 percent, and significantly, an employer rating of 95 percent.5

George and Lillian lived in Edmonton for another seven years after George completed his apprenticeship. During their first winter together as a married couple, George and Lillian lived in a rented suite in Edmonton. The following year, George and his dad, Louis, built a duplex. George and Lillian moved into one half, while George and Louis worked on the other. George also continued to work for Hume and Rumble. After a year living in that home, they purchased a lot in a good neighbourhood in Edmonton, and eventually sold the duplex.

“Human Rumble” — George Evanoff, second from the left, with colleagues at Hume and Rumble in 1956.

George, again with his dad’s help, built a house on the new lot in the summer of 1957.

John remembers that both George and his dad were stubborn, and he could never quite picture the two of them working together. But Lillian said that she didn’t see any friction, and John admitted that “it seemed to work,” noting that George’s dad had the necessary experience to undertake the projects. John added that their dad was self-taught and meticulous: “It had to be done right or don’t do it.” This was an ethic that Louis passed on to his children, and it was evident in everything that George did in his adult life.

While the second house was being constructed, Lillian was pregnant with Delia, who was born in August 1957. With George working full-time, all of the work on the house had to be done in the evenings and on weekends. Nevertheless, the house was soon completed, and George and Lillian moved in before Christmas of 1957. Lillian remembered that the house was modern for that time, with a vaulted ceiling and beams. They continued to live there until they moved to Prince George in 1964.

Their first few years together were hard. Lillian described it as a survival period; the main problem was George’s frequent absences for work. For the first two years, George worked mostly in Edmonton, but he still had to go to Calgary for extended periods to complete his technical training. From 1957 to 1961, he was away for even more time, working on the Interprovincial Pipeline in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. George and Lillian’s son, Craig, was born nearly three years after Delia, in April 1960, and while George was there to bring Lillian home from the hospital, he had to leave right away for the pipeline. These extended periods apart lasted until Craig was nearly a year old.

When George was working on the pipeline in Saskatchewan, he came home on leave once a month. Lillian remembered: “He would drive day and night to get home, and then when he got home, he wanted a home-cooked meal, and I wanted a break from the kids. Those were terrible weekends; he was tired, and I was just looking forward to a break and going out. He didn’t see much of Craig as a baby. Delia and I visited him in Regina; we flew down in a Northstar [DC-4] just for a weekend; it was a very rough ride.” In a later interview, George and Lillian’s daughter, Delia Christianson, told me that this trip is one of her earliest memories: “I remember the propellers of the plane, and I remember my dad standing there, watching, pants flapping in the wind, wearing a white shirt and sunglasses, hair slicked back — looking like Sean Connery.”

While George was away in Calgary working on his apprenticeship, he often wrote to his wife. Lillian recalled: “George would come home every weekend, so his letters were just a daily communication. People wrote letters in those days instead of [using] long-distance telephone.” She kept the letters for many years:

Once, when my grandchild was visiting, after George died, she asked me what was in a chest. I told her that it was just a bunch of old letters, but she begged me to just see one letter. So I pulled one letter out and read it, and I said “OK, you can read this letter.” We were married by then; he was spending two more years at technical school in Calgary, but he would write every day. My granddaughter emailed her mother, Delia, and said “Grandma allowed me to read one of Grandpa’s thousands of love letters!” She was so thrilled that she was allowed to read that one letter. George was working for his room and board in Calgary, doing carpentry in the home of a friend of his parents, and that was partly what was in the letters; as well as occasional ski trips with his friends. I didn’t want my family to read them, but later I was told that it was very important that my granddaughter could read that letter.

While their children were small, Lillian and George would take them camping, sometimes to Jasper by train before the highway was completed from Prince George. Lillian recalled that Delia was a very social person, and Craig’s friends were always calling on him. She noted that George knew how to play with the kids, adding that “sometimes it got a bit rambunctious, and I had to separate them.” Years later, when he was visiting Delia in Kimberley, George had once told me that he was left in charge of his grandchildren, who were still quite small, and when Delia returned, he was teaching them how to climb a wall.

During his years with Hume and Rumble, George Evanoff had many interesting experiences. Lillian remembered that he was something of a daredevil and would get good pay for climbing microwave towers. Craig related a story that his dad had told him of the time he was working on a radio tower: “He was on a ladder, when the guy working above him dropped a hammer. In those days they didn’t wear safety belts and the hammer came down and hit George on the head, about a hundred feet off the ground. He almost became unconscious and fell, but one of the ladder pieces ended up under his arm, and he hung there while he got his wits back together.” George had once confided to me that on another occasion he and another person were assigned to wire a pipeline building. When they reached the site, they found that a fierce wind had blown the structure over on its side. Wondering what to do, George proposed that they just wire it anyway — perhaps the only building ever to be electrically wired while lying on its side.

George’s responsibilities extended beyond pipelines, and included the electrical system and panel in a new brewery that was built on the south side of Edmonton. After touring the brewery, George’s cousin Bob commented that “George saved the company a lot of things; unbeknownst to them, too. He had everything so programmed that the machine would almost be thinking for itself.” According to Lillian, the manager of Hume and Rumble, George Firth, liked George Evanoff because he was dependable. He put him in charge of a crew and gave him a lot of responsibility. Like some of George’s other work relationships, this one extended into a friendship outside the job.

Reconnecting with the Outdoors

During his years in Edmonton and before making the move to Prince George, George Evanoff’s life had settled down sufficiently to allow him time to resume some outdoor pursuits. At that time, George had not yet taken on the mountain-based activities that he was known for in his later years, and was still mainly interested in fishing and hunting.

George and Paul Kindiak were both living in Edmonton, and Bob was still in Edson, where he was busy with the family farm. Bob had a cabin there that George could use, and this helped provide a connection to the countryside of their youth. The focus in this three-way friendship had shifted to George Evanoff and Paul Kindiak; they became fast friends through their outdoor pursuits. Occasionally they were joined by Bob and/or George’s brother, John.

One of Bob and Paul’s projects in the early 1950s was to build a new sixteen-foot canoe, a superior craft to the pirogue that almost took George and Bob’s lives as youngsters. They made it from waterproof mahogany plywood. It was wood-framed, wetted, steamed, bent, stretched, glued, clamped, and screwed to the framework. After drying, the outer plywood was completely covered with fibreglass cloth, and resin applied two or three times to finish it. Paul showed me this canoe in his backyard during a return visit to Edson in July 2006. Although patches marked various misadventures, the now forty-five-year-old canoe looked well cared for and nearly as good as new. Paul, then seventy years old, but looking fit and twenty years younger, was still using the canoe. The canoe was hard to tip because of the unusual concave keel that they had designed. The three of them once took a whole bull elk across the McLeod River in the canoe with almost no freeboard and without mishap.

Using this canoe, they fished the creeks and beaver dams twenty kilometres northwest of Edson that were part of Little Sundance Creek. There, beaver dams had flooded the muskeg valley, and the only access into and out of the central areas of the stream was via channels made by the beavers. This was where George developed a passion for fly-fishing. Paul described how they could often see fish jumping everywhere, although it was difficult to fly cast because of willows and other bush close to shore. On one occasion, Paul, George, and his brother, John, came out to Edson to fish the Little Sundance Creek beaver ponds. The three of them packed the canoe about a kilometre down a seismic cutline, and then across almost two hundred metres of muskeg to a large beaver dam. George became so excited that he started fly casting as soon as Paul and John paddled out into the first stretch of open water. Paul remembered that he sat at one end of the canoe, with John at the other end and George in the middle: “Each time George fly cast, in his excitement he would lean over one side, John and I had to lean over the opposite way to avoid George dumping the canoe.”

On another occasion when they were fly-fishing at Little Sundance Creek, an eclipse of the sun caught George, Paul, and Bob by surprise. They were out in the beaver ponds with the canoe, and although the fish were biting, they had to work for them. Suddenly, George noticed that the light had changed, as if the sun had gone behind a cloud, except that it was darker. It became as dark as evening, and the fish began jumping and biting so much so that they couldn’t get them off the hook and into the boat fast enough.

Another favourite place to fish was Beaver Creek, a tributary of the Athabasca River, located fifty kilometres northwest of Edson. The Athabasca Hills and Beaver Creek area was once home to the Grand Prairie Trail.6 Bob related the story of an epic day that he, George, John, and Paul had while fishing the creek:

The rivers and creeks around Edson were an important part of the outdoor life of George Evanoff both as a child, and later as a young man.

The creek was a beautiful stream, crystal clear with many boulders and fast water tumbling into various sized pools where we would catch up to six or more rainbow trout, depending on the pool size. We all raced downstream from one eddy or pool to the next, to try and be the first one to catch the first fish or two. The result was a stampede all the way down the creek, the pools and fish getting bigger the farther downstream we went. We simply forgot ourselves in our fishing enthusiasm until we almost got down to the Athabasca River.

By then, it was nearly evening and they had to hike a long way back uphill. They reached Bob’s place at midnight, and George and Paul still had to drive back to Edmonton; they arrived there just in time to start work on Monday morning.

Paul Kindiak

George Evanoff, right, and Paul Kindiak with “arrowed lynx” in Bob’s cabin in Edson around 1961.

When I first met Paul Kindiak in Edson in July 2000, he was still employed as engineering coordinator with the Town of Edson. When we met again six years later, he had retired but was still busy. Although three years younger than George Evanoff, Paul had clearly been a maturing influence on him regarding their shared outdoor interests. Paul explained that it was in 1960 and 1961, when George was in his late twenties and already married, that they began going back to Edson for fishing trips. Paul and George would drive down from Edmonton together. Paul stayed with his mother in Edson, and George (and John, when he came along) stayed at Bob’s cabin. Bob’s cabin was a substantial structure, with a rock fireplace and interior wood panelling that may have given George ideas for his future ski lodge in the North Rockies. Paul taught George how to fly cast on the lawn in front of the cabin, and George used to practise there.

Paul showed me a black and white photograph of him and George with a lynx they had shot with a bow and arrow while walking thirty-two kilometres south of Edson and the McLeod River on a circular, early-season scouting trip for elk. The photo was taken in Bob’s cabin in 1963. Bob Evanoff told me that Paul pulled up to ninety pounds, a lot for his size, but that it was Paul’s skill with the bow, and not just strength that counted.

Paul also talked about George Evanoff’s first bull elk, taken just south of the McLeod River. Paul had called up the elk using a tube made from a cow parsnip stem. The elk began answering, and Paul told George to stay in the pines while he circled around. Paul said: “We heard the elk crashing its antlers against trees, and it approached George, crashing its antlers some more against pine trees. George became very excited and shot at forty yards. The elk ran thirty or forty yards and dropped. It was a nice six-point royal bull, and dressed out at 750 pounds. George was big-eyed when he got that elk.”

Paul Kindiak described George as “very active, very interested in wildlife, hunting, and fishing; he loved the outdoors. He challenged anything and would walk whatever was required to do it — very energetic. He could not often be found lying around, except after a trip. He always talked about hunting and fishing, and was always looking for new things to do in the outdoors. He was not so keen on bow hunting, but was more interested in fly-fishing, rifle-hunting, calling elk, and learning more about wildlife and the lives of animals: how they survived, what they ate, how to track them.” Paul taught George the difference between the tracks of a white-tailed deer and a mule deer. Many years later, when George was a member of the Prince George Search and Rescue group, he learned a different tracking skill — following people who were lost in the bush.

After moving to Prince George, George’s passion for hunting gave him an excuse to explore many remote areas of northern British Columbia. Paul has an old colour print of George, with a familiar grin on his face, holding up a full-curl Dall ram. Perhaps George gave the photo to Paul as a thank you for helping to introduce him to that aspect of the outdoors. The two of them might have shared a lifetime of outdoor adventures together, but George’s career was about to take him across the familiar Rocky Mountains of his youth into north-central British Columbia.