Читать книгу The Mountain Knows No Expert - Mike Nash - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSettling in British Columbia

Chapter 4

When George Evanoff moved to Prince George in 1964, he set about establishing himself in a community that was just emerging as an industrial forestry centre, and a transportation and service hub for north-central British Columbia. In addition to its rapid economic growth in the 1960s, Prince George was, and still is, surrounded by some of the best outdoors to be found anywhere in the world — George Evanoff soon made good use of the opportunities that the environment presented, and his interests and activities veered off in many directions.

Lillian Evanoff described how George received the opportunity to work in British Columbia: “After a few years, George got a job with the pipeline in Prince George. Dick Littledale,1 the engineer in charge with Interprovincial Pipeline, had known George in Edmonton before getting a job in Prince George with Western Pacific Products and Crude Oil Pipelines Ltd., a company that later became Westcoast Petroleum. Dick was impressed with George’s work on the Interprovincial Pipeline and needed someone to do the electrical contract work for him, so he asked George … if he would like to come and work here.” Dick and George became good friends and shared several early hunting trips in northern British Columbia.

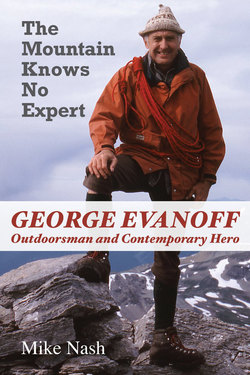

George, Lillian, Delia, and Craig Evanoff in their new Prince George home, 1966–1967.

George and his family moved to Prince George in April 1964; they drove “there via the northern route, because Highway 16 wasn’t finished yet.” At first, they lived in a duplex while George designed their new house. A contractor built the house while George did the electrical work and some of the finishing. His workplace was located just off Fifteenth Avenue in Prince George, a few blocks west of their new home. Its well-equipped shop catered to mechanical as well as electrical projects, and was home to more than a few of George’s personal and volunteer undertakings over the years.

Prince George and Its History

Prince George’s origins date back to the heyday of the fur trade, as that historic commerce pushed into Canada’s farthest reaches. In 1807, Simon Fraser of the North West Company established a camp at the site of the present-day community on the banks of the river that now bears his name. Within two years the camp was abandoned. In 1823 the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort George in the same general location. Simon Fraser was not the first white man to visit the site of present-day Prince George. Alexander Mackenzie had passed through there in 1793, on the last leg of his journey to cross the full width of the North American continent, more than twelve years before Lewis and Clark succeeded in a similar quest in the United States. As he passed through the area that later became Fort George without mentioning it in his journal,2 Mackenzie instead described the cutbanks on the eastern side of the river: “The banks were here composed of high white cliffs, crowned with pinnacles in very grotesque shapes.”3 Those cutbanks and pinnacles are comprised of glacial silts originating from a large post-glacial lake that used to lie over the surrounding area. Two hundred years later, George Evanoff built a recreational trail atop the Fraser River cutbanks overlooking downtown Prince George.4

Prince George lies near the geographic heart of British Columbia, at the confluence of the Nechako and Fraser rivers, in the traditional territory of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation. The two rivers carved out the bowl that is the site of much of the present-day city, and they form the backdrop of the Heritage River Trail System that George and Lillian Evanoff used often.

The City of Prince George was incorporated in 1915, following the arrival of Canada’s second transcontinental railway (Canadian National Railway), the same railway that played a key part in the life of George’s parents on the other side of the Rockies. Lumber was a mainstay of Prince George’s economy in the first half of the twentieth century, and in the 1960s, rapid growth took place with the arrival of pulp mills, highways, airlines, pipelines, and hydro power. A process of consolidating timber rights and many hundreds of small bush mills into a few large sawmills began. The new sawmills were integrated to supply wood-chip fibre to the pulp mills, utilizing what was previously considered a waste by-product as a raw material. With the arrival of the pipelines came George Evanoff.

Today, the city is home to two advanced educational institutions: the College of New Caledonia, where George Evanoff furthered his technical education, and the University of Northern British Columbia, where in his last years, George Evanoff was invited to speak to students, advise on recreation opportunities, and participate as a lay advisory member of a grizzly bear study conducted north and east of the city. The city’s cultural life includes a symphony orchestra, to which George and Lillian were regular subscribers.

Because Prince George is centrally located in British Columbia, the city’s residents can travel in any direction without being constrained by borders or shoreline. It takes less than two hours to drive from Prince George to the Cariboo and Rocky mountains, and only half a day to travel to Jasper National Park. Prince George is surrounded by wild backcountry where it is still possible to explore untrodden ground within short reach of home, an experience that George Evanoff eagerly pursued.

New Opportunities

After completing his new house, it wasn’t long before George Evanoff again turned his attention to the outdoors. At the top of his list of favourite activities were hiking, fly-fishing, and hunting in the summer and fall, and skiing in the winter and spring. In the days before the completion of the Yellowhead Highway east of Prince George, there were few serious local ski opportunities, although a ski hill did operate on Tabor Mountain, just east of the city. George started skiing there in 1964 and 1965, initially buying rope-tow tickets for himself, while Lillian and the children skied around at the bottom of the hill. Still, he yearned for the big mountains of the Rockies, and it wasn’t long before he turned back to the CN railway as a means of accessing Jasper, this time from the west instead of the east.

Lillian remembered the family’s trips to Jasper in 1965 and 1966: “We would get onto the train in the evening, put the kids to bed, and arrive in Jasper at 8:00 a.m. the next morning. Then, George would run into the baggage car and throw our skis out. We had to hurry, as we had to check into the Athabasca Hotel where we used to stay, and catch the bus for the ski hill at 8:30 a.m.”

According to his son, Craig, the train crew would be annoyed with George because he would barge his way into the baggage car to throw skis, bags, and other stuff out. Then they would run from the station to the Athabasca Hotel in a panic. I asked Lillian if they ever missed the bus. “No, no way!” she said emphatically:

We used to spend all day up at the ski hill. On the first trip, Craig was about five years old, and we weren’t going to buy lift tickets for the kids as it was too much money; we thought they would just play at the bottom on the rope tow. I was just learning how to ski and George and I were going up the steep slope on the T-bar when George said, “Look who’s behind us!” Craig and Delia were riding up the steep slope. I don’t know how the kids got on the lift, but I was so scared … We bought them lift tickets from that moment on. We skied Saturday and Sunday, and took the night train back, and arrived in Prince George on Monday morning.

Delia later told me that she and Craig had simply snuck onto the ski lift that first time. “It was my idea,” she said, sounding much like her father.

From this beginning, Craig went on to become a mountaineer with a number of significant ascents, as well as a professional member of the Canadian Avalanche Association (Level 2), and a certified ski guide with the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides. Delia excelled as a runner, winning all of the ten-kilometre races that she entered as an adult, and setting a Cranbrook, British Columbia, ten-kilometre record that held for fifteen years. After that, she ran the Vancouver Marathon before turning to cross-country ski racing. She entered the famous Cariboo Marathon fifty-kilometre cross-country ski race three times, finishing in the top three women, and winning her age class on each occasion. She finished first overall among the women in at least one of the races. Delia remembered that once when George and Lillian came to watch her compete, her dad was so excited that he inadvertently skied up and down the racetrack at the finish line and had to be told to stand back. Delia later took up bicycle touring, which she continues to enjoy.

Professional Standing in British Columbia

After moving to British Columbia, George Evanoff applied for membership in the Applied Science Technologists and Technicians of British Columbia (ASTTBC) as it is now known, which is the professional association responsible for registering technology professionals in the province.5 George Evanoff was registered with the association as a senior engineering technician on May 24, 1968, in the electrical engineering discipline, and he was reclassified to applied science technologist (AScT) on October 28, 1982.6

In his original application, dated October 16, 1967, George described his job as maintaining existing electrical and instrumentation equipment, analyzing and correcting equipment problems, advising and instructing operating personnel, preparing training courses and texts, preparing technical reports and studies, selecting new electrical equipment and preparing cost estimates, assisting in new design work, preparing drawings and specifications, and supervising new installations. These professional skills were evident in George’s many outdoor interests, such as installing and maintaining ski lifts, and designing and building avalanche and backcountry rescue gear, and eventually designing his ski lodge.

Lillian recalled that George was proud to receive his AScT seal so that he could at last stamp his own professional work, without asking an engineer to do it. George’s enthusiasm about using his own seal speaks to the fact that he was not shy about standing behind his work. George Evanoff retained his professional membership in the ASTTBC for nearly five years after his retirement, terminating it on October 24, 1995.

Work Life

Don Doern was the manager of pipeline operations for Westcoast Petroleum Ltd. at the time of George’s retirement from the company in early 1991, and he spoke at George’s remembrance service in November 1998.7 When I contacted Don Doern in 2005, he explained that George Evanoff was a one-of-a-kind type of guy:

George started with the company in 1964, and retired in 1991. It was during this time that the pipeline underwent a huge transformation, by doubling the number of pumping stations, tripling its horsepower, and almost quadrupling its pumping capacity. It was also transformed from a totally manned, twenty-four/seven system to being fully automated with a state-of-the-art computer-run control system. George was instrumental in developing the plans and overseeing the expansion projects on the electrical side. In between major projects, he constantly tweaked systems so they operated more efficiently, and provided insight for future projects. George and his fellow employees in the technical planning departments could truly make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

But Don also noted another side of George Evanoff’s character:

Anyone who knew George knew that he was an individual of boundless energy; everywhere he went was at the dead run, but following close on his heels was disaster just waiting to happen. Early in George’s career with the pipeline, he was working at the Kamloops Tank Farm on some upgrades. He was running back and forth from the control room to the tank manifold area when, on one trip out the door, he managed to hook his coat on the carriage-return arm of the superintendent’s prized typewriter. This was in pre-computer days, and no one was allowed to touch this typewriter without the express permission of the superintendent. George’s jacket pulled the machine off the table, where it crashed to the floor and disassembled itself into its many component pieces. George was oblivious to this incident until he returned from his trip out to the manifold, and found the superintendent sitting in a chair staring woefully at his prized possession lying on the floor. George, in his most cherubic voice asked, “What happened here?” We were uncertain how he managed to survive that day, but thankfully he did.

Despite George Evanoff’s propensity for near-disaster, Don Doern remarked that “he was one of the most intelligent, thoughtful, and caring men I have ever worked with. He always had time for you, and was eager to teach you new things if you were willing to learn. The pipeline truly benefitted from his presence and he was sorely missed when he retired.”

Vehicle Woes

Don Doern recalled an occasion when George borrowed a company truck for the weekend to get some firewood for the winter. On Monday morning, “he reported that ‘he had had a bit of an accident.’” Doern noticed that the cab of the truck was severely dented in the middle, almost crushed down flat, and that the rear window was missing and the front windshield was broken. According to Doern, “George explained that he had found ‘the perfect birch tree’ and positioned the truck in such a manner that he would not have to carry the cut-up tree very far. As fate would have it, Mother Nature decided to play a trick on him and decided to soften the fall by having the tree land on the cab of the truck. To add a certain amount of horror to the story, Lil was sitting in the truck at the time. George had instructed her to stay there, where it would be ‘safe.’”

This was not an isolated incident with a vehicle — George was well-known for a series of driving mishaps that likely began with the picket-fence incident that took place while he was working in Toronto. In fairness, he spent decades driving in severe winter weather on back roads and mountain highways where problems were inevitable, but his scrapes became legendary nonetheless. As a pipeline coordinator, George was provided with a succession of company cars for business and personal use, and more than one of these vehicles did not survive unscathed. On one occasion George was returning from an avalanche course and skidded on a slippery mountain road; the rear end of the car landed in a snow-filled ditch after surmounting a concrete barrier. Apart from its compromised position, everything seemed to be fine with the vehicle, so he gunned the engine and tried to drive out. Nothing happened. George got out of the car to see how badly his wheels were mired, and discovered that they were not just stuck, but were missing altogether, along with part of the drive train.

George was a skilled driver, but like many of that ilk, he sometimes pushed his skills to the limit, usually on unpaved forestry roads while negotiating snow, ice, or loose gravel. Paradoxically, on paved highways he drove with meticulous attention to the rules of the road, rarely speeding or overtaking incautiously. On one occasion, George and I were driving back from the Cariboo Mountains along an ice-covered forest road. The road surface was smooth — seemingly better than pavement — and we were cruising along easily at over a hundred kilometres per hour. It was a case of blissful ignorance, because upon exiting the vehicle when we stopped to relieve ourselves, we both fell flat on our backs on what proved to be an impossibly slippery surface of meltwater on smooth ice. On another occasion, one of George’s friends was driving home with him after a day of skiing in the McGregor Mountains. Turning the car around to start the trip home, George backed hard into a snowbank, and unknowingly plugged the exhaust pipe with snow. A short while later while cruising along, the muffler system blew up.

George’s misadventures with vehicles were not limited to the wheeled kind, as evidenced by the time he put one of his heavy ski-boot-clad feet through the bubble of a Jet Ranger helicopter during one of his avalanche patrols. I had joked with George after that incident that it was a good thing he didn’t have a pilot’s licence, as aircraft are much less forgiving than cars — he readily agreed. George’s neighbour, Bob Wiseman, summed it up after relating how George’s car rolled backwards out of his driveway, crossed the street, and banged into the back of Bob’s car, which was parked in his own driveway: “George just didn’t have any respect for vehicles, they were just there for him to use, as hard as he could.”

Purden Ski Hill

A few years after arriving in Prince George, George Evanoff turned his attention to a new ski hill that was being developed at the western end of the Cariboo Mountains, close to his new home. In the late 1950s, the grade for the future Highway 16 east of Prince George to McBride was being cleared, and by 1966 the new highway had been completed between Prince George and Purden Lake, sixty kilometres east of the city. The road initially had a gravel surface, but people quickly saw the recreational potential of the Purden Lake area. One such man was Joe Plenk, who later worked on the new ski hill development above the lake, blasting rock and clearing brush and trees. Joe also became known for his volunteer efforts a few kilometres east of Purden, where he worked alone, cutting and maintaining trails to and around the historic Grand Canyon of the Fraser, now a provincial park, for many years.

Joe Plenk was not a stranger to the Purden area. As early as March 1962, he travelled from Sinclair Mills on the CNR right-of-way to ice-fish on Purden Lake. Then, in 1967, a group of Prince George residents decided to pursue the prospect of a ski hill development above Purden Lake. It would be located in the first really high country east of the city on the new Highway 16, at a spot where the land nearly reached subalpine elevations. In the winter of 1967–68, a snow survey was completed on Purden Mountain; three and a half metres of snow were measured in the Purden Bowl at the heart of the proposed development. In 1968, construction of the ski hill began. The plan was to put in a road from the highway up to the intended base of the ski hill, and from there to install the towers for the chairlift. Unfortunately, that summer was very wet, and although the road was completed, Joe Plenk remembers that it was mostly eight inches of mud, and the towers had to be assembled down below. At first, not much clearing was done for ski runs, which were mostly laid out in alder glades.

The first season of 1968–69 was nearly a total loss. In March 1969, an unseasonable early rainfall caused the established ski hill on Tabor Mountain, closer to Prince George and at a lower elevation, to ice up. It was unable to open. The new ski hill at Purden was just above the snow line, and Joe remembers that somebody on local radio announced that Purden had six inches of powder snow. Within two hours, carloads of people started to arrive, and soon afterwards the food concession ran out of supplies. The Purden ski hill didn’t look back after that, although its financial viability still hung in the balance. A man named Bob Buchanan took over as president in 1969, and he was able to persuade one of Prince George’s iconic business establishments, Northern Hardware, to provide building materials on credit. This provided timely relief, and helped leverage further bank support.

That was also the year that George Evanoff got involved with the new ski hill. Lillian remembers that once he had heard about the ski hill being developed near Purden Lake, the couple was “there constantly.” George had earlier joined the ski patrol at the Tabor Mountain ski hill, and within a year of Purden opening, he became the ski patrol leader there. It was a position that he held for eleven years, until he turned his attention to planning a backcountry ski lodge. Because of the cash flow situation of the new ski hill, many people who worked there during the first few years, including Joe Plenk and George Evanoff, were paid in small numbers of shares. In George Evanoff’s case, most of his contributions outside of the ski patrol involved electrical work on the ski lifts and generator.

Right from the start, George demanded that things be done correctly; for example, he insisted on adding a transformer to the generator after the first season. “Whenever George spoke,” Joe said, “Bob Buchanan was full attention; no nonsense.” Joe Plenk, who was a steam engineer by profession, worked on clearing trees and brush at the new ski hill, and putting in cement forms and steel. He also did some dynamiting, for which George loaned him his blasting book that showed him how to set the charges for desired effect. Joe described one incident that demonstrated George’s proclivity for doing things right.

It was in the early 1970s, and Joe was using dynamite to lower a rocky ledge that was being used as a natural ski jump near the top of the hill. After he had set the charge under a rock, lit the fuse, and retreated to cover, he realized that the telephone line that was part of the chairlift’s emergency stop system was directly over the rock. Too late, he watched in dismay as the debris from the explosion severed the line. Joe’s attitude was that since he had broken it, he would fix it. The next day, he hauled ladders and equipment up to the site, rigged a scaffold to reach the line, and spent many hours meticulously replacing telephone wires, individually wrapping them with electrical insulation tape. He thought he had done a pretty good job, but later, when he described the work to George Evanoff, George replied bluntly, “Not good enough!” So George hauled his own equipment up to the top of the hill and laboriously replaced Joe’s work, this time putting electrical sleeves on the wires.

George’s concern for safety was always paramount. He once told me about a tragic accident that occurred at Purden, and his immediate response to it. Joe Plenk also described what happened: A skier had gone over a natural jump and had collided with another skier below, and both of them hit a lift tower. One of the skiers died at the scene, from major chest injuries that resulted from the force of the impact with the tower. Shortly after the accident, without waiting for an inquiry or consulting anyone, George erected protective netting around the towers.

One of the ski patrol’s responsibilities every year is to practise a chairlift evacuation. In the event of an extended breakdown or stoppage of the lift mechanism, it is essential to be able get skiers down from the chairs as quickly as possible, especially in cold weather. Organizing and practising this evacuation was one of George Evanoff’s favourite jobs, and he was understandably upset when a real lift evacuation finally happened on a day that he was out of town, and he missed the big event that he had practised for. George had done his job well, however, and the other patrollers accomplished the task without incident. Notwithstanding his personal disappointment, he had met one of the essential challenges of leadership by ensuring that things ran well in his absence.

The ski hill’s first president, Bob Buchanan, recalled how he first met George in the fall of 1969 on Purden Mountain as the operation was getting started:

Some avid Prince George skiers had started building a ski area and it had struggled along for a year, but was unfinished and undercapitalized; there were no paid employees, and the lifts, ski runs, equipment, and lodge were unfinished. The company that supplied the ski lifts was owed a large debt, and was threatening to remove them as they had another buyer. George had organized a ski patrol for the hill, and he was out doing training and other things on the weekend. We introduced ourselves and I told him that we were trying to get things going, and that some volunteers who were to install the safety system and communications on the new T-bar had not shown up for the second weekend in a row. It was causing considerable problems since we needed a government inspection before we could use the lifts. George immediately decided to do the necessary work himself, and shortly the lift was up to Code, inspected, and ready for use.

When the operational company required more money to continue, George became a shareholder, and was paid a token amount in shares for the many jobs he did on the ski lifts, equipment, and ski lodge. Being a helpful and concerned shareholder, he was also imposed upon to become a director of the Company. The ski area was a marginally profitable operation, existing as it does at a rather low altitude. It was kept going in the early years by shareholders who loved to ski enough to keep it operational through a series of financial crises while it paid off its early loans … Most of all, I remember George helping out at critical times: such as replacing a broken gearbox on the chairlift, working with only a few people for most of the night, to be ready for the weekend. We became personal friends, and I have many memories of skiing with him.

Bob Buchanan has many other memories — a canoe-fishing trip on the Bowron, helicopter skiing in Valemount, and climbing a mountain one spring above the treeline. But it was George’s exceptional talent as a technician that stood out. Once, a rather large and expensive snow groomer and packer that cost $150,000 developed a glitch of some sort, and an aircraft technician who was at the hill examined it to see if he could find the electronic problem, but couldn’t help. Later, when Bob had George take a look, he found the problem in a short time, and corrected it. “You came to expect that of George, but sometimes it was surprising.”

Craig Evanoff has recollections of his father’s intense involvement with the operating equipment at Purden ski hill: “If we were going hiking, for example to Sugarbowl Mountain,8 we always stopped at the ski hill on the way.” He remembered that, as kids, they would wait for what seemed like hours as George checked out some aspect of the lift system. I had similar memories of occasions when George and I were going hiking or backcountry skiing in the area; George would invariably stop at Purden ski hill on the way home to check on something. In the 1990s, George was no longer involved with the hill, and when a new chairlift was added, Craig, who was by then working as a forestry technician, did the layout of the new runs. He bushwhacked up and down the forested slopes about five times before settling on the eventual locations, noting that in the end, they were roughly based on what his father had already mapped out in anticipation of such an expansion.

Both of George Evanoff’s children were involved in ski racing at Purden. To support this activity he organized a summer ski school at Smithers, for which he built and installed a portable rope tow on Hudson Bay Mountain each summer for three or four years, taking advantage of the snow that lingered there well into July. Craig recalled that the same portable rope tow also saw service at the Purden ski hill.

The hill gave George an outlet for his boundless energy and many talents. The ski patrol helped him to develop his flair for leadership and mentoring. He acquired new skills through first-aid training with an emphasis on field improvisation, and he was afforded regular opportunities to put them into practice. It also gave him the impetus to develop the snowcraft skills that led to his avalanche work.

George Evanoff sold out his interest as a shareholder of the Purden ski hill when he built his North Rockies Ski Tours lodge, and after that, he was too busy with his other interests to have much further involvement there. Yet only a few days before George died, the electrician who was working on one of the old ski lifts was having difficulty — there were no longer any drawings, and he wasn’t familiar with the old equipment. He asked if the electrician who understood the equipment was still around; he didn’t want to bother him with the actual work, but felt that it would be helpful to talk with him for fifteen minutes. George’s reaction was predictable. He drove the seventy kilometres out to Purden and spent the whole day helping the electrician work on the controls that he had designed and installed many years before.