Читать книгу The Mountain Knows No Expert - Mike Nash - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

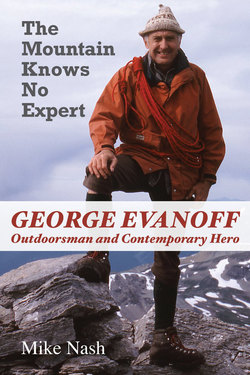

ОглавлениеPath of a Hero

Prologue

This book began as an idea while hiking with George Evanoff in Canada’s Northern Rocky Mountains on a Saturday morning at the beginning of the Thanksgiving weekend in 1998. Exactly two weeks later, on Saturday, October 24, George Evanoff died on a nearby mountain ridge after an encounter with a grizzly bear.

I mentioned the book idea to George Evanoff during that October 1998 trip — the last of many that we had taken together over a nearly twenty-year period. Then, before we had time to digest what we might be getting into, he was gone. The idea did not go away, however, and a few months later I met with George’s wife, Lillian Evanoff, his son, Craig Evanoff, and Craig’s partner, Bonnie Hooge, to talk about writing his story posthumously. Our first conversation took place after dinner in Lillian and George’s home where we reminisced over tea and a tape recorder about an individual who had inspired many outdoor enthusiasts in north-central British Columbia. Ten years on, the result is a book that tells the story of a man who began his time on earth with the free spirit of a first-generation rural Albertan, born of Macedonian immigrants in the 1930s, who went on to become synonymous with the outdoors in British Columbia. George Evanoff never lost his youthful spirit, and gave back to society in his later years for the inspirations and opportunities that he had received.

George Evanoff grew up in the small town of Edson in west-central Alberta, east of the Rocky Mountains and Jasper National Park. The North Rockies were central to George Evanoff’s being, as he spent the first half of his life living about a hundred kilometres to the east of them, and the latter part a similar distance to the west. These mountains provided him with a constant source of inspiration and fulfillment.

George’s story is also about role models and mentors, and their lasting impact on successive generations.1 Several individuals helped shape the teenage George Evanoff in Edson. Among them was the Honourable Norman Willmore,2 after whom Alberta’s Willmore Wilderness Provincial Park was named, and who first introduced George Evanoff to skiing in the mountains. During our first meeting in early 1999, Lillian Evanoff explained that “Willmore definitely had a very big influence on George; he took any kids from the town of Edson who were showing sign of interest in skiing to hike up Whistlers, and later Marmot Basin in Jasper, before those areas were developed. George was amazed that this man would take the time to take him there.” The greatest influence on young George Evanoff was his cousin, Bob Evanoff, who introduced George to fishing, hunting, and canoeing at an early age.

I knew George Evanoff during the last twenty years of his life, the period when he had the most impact on the outdoors people of north-central British Columbia. I met him at the tail end of the big-game hunting trips that he used to take in the mountainous wilds of northern British Columbia, adventures that honed his outdoor skills and backcountry ethic before he exchanged his rifle for binoculars and a camera. Years later, I retraced his steps to some of the remote places that he had been, on extended backpacking trips of my own, where I gained a deep appreciation of his exploits. You will experience some of these quests through anecdotes from George’s journals and hunting partners; and in George’s own words in the chapter, “Dall Rams the Hard Way.”

In the early 1980s, George turned his focus to introducing others to north-central British Columbia’s backcountry, just as Willmore had done for him. Notable in this respect were several week-long trips that he organized and led to the area known as Kakwa, which he later championed and helped to become a world-class Rocky Mountain park.

George Evanoff spent the first half of his life living a hundred kilometres to the east of the Rockies, and the latter part a similar distance to the west.

George Evanoff’s meticulousness and attention to detail were evident in everything he did. In going back through some of George’s files, Lillian commented that he planned every detail on paper, right down to the specifics of getting people in and out of the helicopter during a ski trip. I first encountered George Evanoff on such a trip in February 1979, when I participated in an avalanche course that he was teaching to backcountry skiers and search and rescue volunteers. I later assisted him with some of the avalanche and outdoor safety courses that he taught every year to increasing numbers of recreational and industrial backcountry users. Twice I found myself high on mountain ridges in arctic-like conditions, helping him to set dynamite charges to remove threatening snow cornices.

George had his fingers in many pies outside of his profession as an electrical coordinator for a pipeline company, but the one that stood out was avalanche safety. During the period from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, public appreciation of the risks posed by avalanches in British Columbia’s backcountry was not as high as it is today, and there were few avalanche-savvy people in north-central British Columbia. It is impossible to know how many lives George Evanoff saved through the know-how that he passed on, because you don’t hear about non-incidents. I do know that he influenced me many times to take a safer course in the mountains; yet he refused to allow anyone to call him an expert despite his considerable outdoor knowledge and experience.

George Evanoff and I were both members of the Prince George Search and Rescue group in the early 1980s, and I witnessed his unabashed joy the day after he found and carried two small, lost children out from rain-soaked bush during a tense night search. It was easy terrain by his standards, but because of the darkness and miserable weather, time was of the essence. I have no doubt as to the speed and determination with which he hit his assigned area, and his satisfaction with the outcome. Dave Snider was the search leader that night. An officer of the armed forces reserves and leader of a local cadet corps, Dave later told me of the sheer delight that George displayed when he emerged from the bush with the lost kids, and that joy was still evident to me the next day.

I was directly involved with George in the discovery and first exploration of Fang Cave in the McGregor Mountains. This discovery led to the establishment of Prince George as one of Canada’s foremost caving areas. According to Jon Rollins’s definitive book Caves of the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains, Fang Cave is “one of the finest caves in the Rockies.” George and I also participated in nearly a decade of public land use planning meetings regarding an area similar in size and geography to the country of Switzerland. Throughout this process, George was soft-spoken and generally didn’t talk unless he had something significant to say. The effect was that the noise level in the room dropped when he took the floor as people strove to hear him.

I watched George Evanoff assemble and pre-build a ski lodge in Prince George in the summer of 1985, and I was there when it was flown to the site in the Rocky Mountains in the fall of that year. I took part in North Rockies Ski Tours’ first shakedown trip the following January when a valuable lesson was learned from an avalanche accident that took the life of a favourite dog named Wrex, and very nearly claimed George’s son and his partner.

I helped George on several trail-building projects, where I learned the essential art of self-preservation by keeping clear of him while he was swinging trail-clearing tools. One of George’s friends was not so fortunate, as George dropped a small tree on him while clearing the Gunn Trail atop the Fraser River cutbanks in the city of Prince George. Once, while cutting firewood, George told Lillian to take refuge in the cab of the company truck that he had borrowed for the occasion, and then accidentally dropped the tree squarely on the roof of the cab. Yet, like all those who helped him with his projects, I came to know the exacting standards that he demanded of himself and everybody else. I remember working with him on the new Torpy Trail in what is now Evanoff Provincial Park, where he made me bushwhack out at the end of the day, declaring (to my consternation): “You can’t walk on the trail yet, it isn’t set!”

I saw first-hand George’s self-proclaimed “Evanoff Torture Test,” as he invariably broke almost all new outdoor equipment that came his way, then later redesigned the items to create stronger and better products. More than one manufacturer of a tent or piece of outdoor safety equipment received an unsolicited letter and professional drawings from George for design improvements.

I watched him make a lightning fast recovery from the trauma of a serious head injury suffered during a fall on the job. I saw him steadfastly endure surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy treatments in a successful fight with colon cancer. It was only during the final days of his six-week radiation therapy in Vancouver that he was forced to cut back his daily regimen of hikes in the North Shore Mountains; instead he walked around the Stanley Park seawall, an activity that most healthy people would consider energetic enough. More than one physician attributed his successful recovery to his high level of fitness and his mental attitude, as he exemplified the “use it or lose it” philosophy of fitness and health.

George Evanoff was a friend with whom I could discuss things from a foundation of shared values. For these reasons, I have adopted a familiar style of biography, often referring to George by first name, and basing part of the latter narrative on my own personal experiences with him. By sharing with you a slice of the time that I, and others, spent with the man, I will give you a sense of who he was and how he touched those around him.

The opening chapter of the book takes place during the Canadian Thanksgiving weekend of October 1998, and the closing chapter narrates events just two weeks later on the nearby Bearpaw Ridge, east of Prince George. Together they cover a very small part of George Evanoff’s life — his last trip to his backcountry lodge, which I was privileged to accompany him on, and a fortnight later, his final walk alone into the mountains and the ensuing search for him, which I took part in. There is a risk that the dramatic events of his last mountain hike could subsume George’s story. Yet for George, a man who lived life in the outdoors to the fullest, what happened to him then could have taken place on any of a thousand other excursions that he had made; he certainly had more than a few near misses. The events of October 1998 were therefore an important part of a life spent walking towards that moment, and I have used them to frame George Evanoff’s story. One cannot know what went through the sixty-six-year-old’s mind as he lay mortally wounded on the Bearpaw Ridge, but he had twice said that his preferred place to die would be a mountain ridge.

I wrote the first draft of these two sections a few months after George’s death, while emotions were still high. The rest of the book was completed eight years later, with the dispassion that time provides. After completing several interviews for the book in British Columbia and Alberta, my life took new turns and another book struggled to the surface.3 While that book temporarily displaced the writing of George Evanoff’s story, it did introduce George Evanoff to its readers, with many index references and a first-edition cover photograph taken by him.

In early 2005, as my push to complete this book began, my wife commented that I was working on a biography of “late local hero George Evanoff.” My first reaction was that George, a modest a man who resisted being called an expert, would have rejected even more strongly the word “hero.” Yet, for the next few days the notion would not go away. I found myself asking, “What is a hero, really?” I found definitions that went beyond the customary ideas of mythology and battle. They included, “legendary figure,” “a man noted for courageous acts or nobility of purpose,” and “a man noted for special achievements in a particular field.” I thought of mythologist Joseph Campbell’s groundbreaking 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which he introduces the hero story common to every human culture. The hero begins his journey as a youth, and inspired by a person or people of wisdom, begins an adventure of his own. In time, he returns transformed into a hero with the power to stimulate others to undertake their own journeys.

George Evanoff lived his own adventure, and later emerged as the hero ready to inspire others, such as students at the fledgling University of Northern British Columbia in the 1990s. Although I heard many snippets of George’s earlier life when I knew him, I didn’t really appreciate the bigger picture until I undertook this project. In that sense this work has been a revelation and further inspiration to me, as it may be to others who knew a part of George’s story.

One telling moment occurred in 1989 when I needed a trustee for an estate document. I asked George Evanoff if he would be that trustee, and after serious reflection he agreed. The lawyer with whom I had been dealing was not available when I went in to complete the documents, and instead I found myself in the office of the firm’s senior partner, Harold Bogle, a prominent citizen of Prince George. As he solemnly explained the importance of the choice of trustee, I had no reason to believe that he had ever heard of George Evanoff, and I was preparing to justify my choice. Then, giving me a cautioning look, he asked for the name of my nominee. His reaction caught me by surprise. His face lit up the instant I voiced George’s name and he said approvingly, “Oh, George Evanoff’s alright!”

This is the story of an ordinary man, born in rough-and-tumble rural Alberta in the midst of the Depression, a first-generation Canadian who instinctively and fearlessly lived his life well. As the book title suggests, George was not immune to mistakes, including perhaps a final misstep on the Bearpaw Ridge, but he was always willing to learn and to pass on what he had learned to others.

Drawing on the words of Bessie Anderson Stanley in her famous 1905 essay on success, George Evanoff left the world better than he found it. His ever-present smile or outright grin when in the outdoors indicated how much he appreciated the Earth’s beauty. He always looked for the best in others, preferring to keep quiet rather than speak ill of someone. He gave the best that he had, enhancing the outdoor experiences of others, and undoubtedly saving lives in the process. He was an inspiration to those who knew him.

For those who never knew George Evanoff, I hope that his story inspires you to experience and to enjoy life in Canada’s outdoors to the utmost, and especially to tread lightly on the land and in the wild mountain environments that we still have in Canada. That was George’s wish when we discussed this project a few days before his death.