Читать книгу The Mountain Knows No Expert - Mike Nash - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThanksgiving 1998

Chapter 1

The morning was clear and cool as we began an hour of bushwhacking to reach the mountainside. There were still yellow and green hues on the trees, and the vegetation carried just enough frost to get us wet without soaking us through. With winter approaching, the bush was quiet, apart from the sounds that we made pushing through it. George Evanoff had invited me to ski with him to his lodge in the Rocky Mountains northeast of Prince George on the Thanksgiving weekend. It was October 1998. Less than a day earlier I had been sitting in my office contemplating the long weekend. Not having any definite plans for Thanksgiving, I had imagined three relaxing days at home, with excursions to enjoy the dramatic fall colours of British Columbia’s interior.

The phone rang; it was George. “What are you doing for the weekend?” he asked.

“Oh, nothing special,” I replied.

“Well, I’m going up to the cabin,” he continued. “Why don’t you come with me?”

Already past his mid-sixties, and a recent five-year colon cancer survivor, George set a pace in the mountains that few people of any age in north-central British Columbia could match. More than a decade earlier, he had conceived of and built a backcountry lodge in the Dezaiko Range of British Columbia’s Rocky Mountains, northeast of Prince George. He used it as a base for a company that he called North Rockies Ski Tours. With his wife, Lillian, he had run commercial backcountry ski tours there for thirteen years. Later, his son, Craig Evanoff, took over the operation, renaming it the Dezaiko Lodge. In the winter months, George flew clients to the lodge by helicopter for four to seven days of backcountry skiing. During the rest of the year he made regular trips to the lodge, usually on foot, to check on the place, do maintenance work, cut firewood, or to just enjoy the mountain wilderness, its wildlife, and its solitude. Located more than fifty kilometres from the nearest permanent human settlement, the lodge’s further isolation from adjacent forest roads was afforded by steep, wooded mountain slopes, and high ridges that had to be traversed to reach the site.

I thought over George’s invitation. The trip to the lodge would mean racing around after work getting food and gear ready, and getting up at five o’clock in the morning for the two-hour drive east to the staging area. I didn’t think of it as a trailhead, as this would incorrectly imply the existence of a trail. The first part of the hike was a three-kilometre walk carrying skis through wet, recent-growth McGregor Valley jungle, where I had gotten lost a couple of years earlier. George had deliberately allowed what had passed for a trail to grow in and all but disappear. The approach hike would be followed by a 1,200-metre vertical climb through the forest, across alpine meadows, and over a ridge, where we expected to don skis for the six-hundred-metre descent to the lodge. We would be alert for grizzly bears as this was an area of frequent sightings, where I had personally had five close encounters in as many years, and George many more.

We would be prepared for winter weather — storms and whiteouts are common in the Rocky Mountains, but as George often pointed out, “that’s how you get the good snow.” Winter comes early enough in the north, and it is easy to question the desire to climb up to it while the valleys below are still green. Part of the motivation lies in the joy of walking in the season’s first embrace of snow and returning to the fall colours below; in this instance, visiting a well-appointed backcountry lodge added further incentive.

Thanksgiving weekends in the Northern Rockies can afford beautiful golden fall colours, with pleasant shorts-and-T-shirt weather and dry alpine meadows stretching to distant ridgetops that are brushed with a hint of white. Or they can produce a metre of new snow at alpine elevations, as was the case during the first hike to the newly completed lodge on the same weekend in October 1985. On that occasion George carried a seven-kilogram turkey up the mountain and all the way back down again after we were rebuffed by thigh-deep snow at the treeline. With several kilometres of higher and more exposed terrain still to cover, and with more precipitation in the forecast, there was a heated debate as to whether, having lacked the foresight to bring skis or snowshoes, we should turn back. With the group evenly split, it was agreed that we would wait for Craig Evanoff and his partner, Bonnie Hooge, who were coming up behind the main party, to cast the deciding vote. Those who favoured continuing on, including George, were sure that youthful enthusiasm would carry the day. In due course, however, Craig, who would later go on to become a certified ski guide, demonstrated that the wisdom of youth sometimes trumps that of age when he arrived with the deciding words, “Are you guys crazy?”

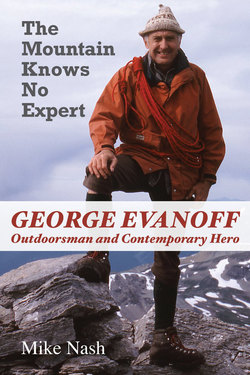

After carrying a large turkey up the mountain, George Evanoff argues in favour of continuing on before agreeing to abort the Thanksgiving 1985 trip to his just-completed backcountry ski lodge.

In the days leading up to Thanksgiving 1985, it had rained steadily in Prince George, but our minds had not been in winter mode, and nobody had thought of snow. Thirteen years later there had been a few days of cool, wet weather in town prior to Thanksgiving, which probably meant some new snow in the mountains. We wouldn’t know how much until we were there, but this time we would carry skis.

The deciding factor to accept George’s invitation was simply that I hadn’t seen much of him for several weeks. This would be a chance to renew our friendship in the type of mountain setting that was its foundation. As we drove out to the Rocky Mountains on Saturday morning in George’s truck, I pulled out a tape recording that I had made from a CBC radio show that had been broadcast a few weeks earlier. It was a chance recording of a fifteen-minute debate between two men who had each written books about bear safety. The authors had differing views on the subject, and the drive out to the Rockies that morning would be a good opportunity to listen to and discuss the debate with George. We had both had many encounters with black and grizzly bears, some of which were shared experiences.

We didn’t start the tape until we were close to the mountains and were driving along the Pass Lake Forest Service Road. As we listened, we were travelling beneath the Bearpaw Ridge where, just two weeks later and a few hundred metres above us, George Evanoff would encounter a grizzly bear that was defending a moose carcass. A few months earlier, he had been appointed as a lay expert in a University of Northern British Columbia grizzly bear study in the northeast Rockies,1 recognizing a lifetime of experience gained in the mountain backcountry. George discussed his thoughts about bears as we listened to the tape.

In his later years, George did not feel that it was necessary to carry a firearm for defence in grizzly country, although an entry in one of his journals suggests that he may have felt differently during his big-game hunting days.2 He knew from experience that you would have to be both skilled and very lucky to use a gun successfully in a surprise encounter with a grizzly bear. But neither did he carry bear spray, which is considered to be a very worthwhile grizzly bear deterrent. I later discussed the circumstances of George’s death with one of the men we had listened to on the tape recording, a man widely regarded as Canada’s foremost grizzly bear expert.3 He told me that while bear spray is somewhat effective in the case of females defending their young, it is really dicey in carcass situations. He stressed that there is an irreducible bottom line with grizzly bears.

In the twenty years that I knew George Evanoff, we talked many times about his experience with wildlife and his feelings about bears. He respected them, and he was not generally afraid of them. That was not always the case for me. I grew up in England, a country where there aren’t any dangerous wild animals, and despite thirty years of roaming Canada’s bear country, I have never quite overcome this aspect of my youth. I have had many grizzly bear encounters that I excitedly described as being close, ranging from a few hundred to only a few metres. During some of those encounters, I was travelling with George. “That wasn’t close, I don’t know what you’re so worried about,” he once told me. But George did occasionally worry about being too close to a grizzly. His neighbour, Bob Wiseman, recounted one such incident to me that took place in the Blue Sheep Lake area of northern British Columbia. Like the Bearpaw Ridge, it involved a carcass.4

At least one other encounter gave George pause during his final hunting trip to the Kusawa/Takhini area of northwestern British Columbia, when he walked alone without his rifle down the valley from his camp to look for two companions, Laurie Marquis and Fred Wuertch, who were scheduled to fly in later. That evening George wrote in his journal:

August 19, 1977 (Kusawa/Takhini): Went down valley about 1730 [hours] to see if Laurie and Fred were coming. Watched for them about one and a half miles below camp. Didn’t see them so headed back at 1830. Seen a cow moose and a grizzly one and a half miles from camp — no rifle!!!!! Saw a goat across valley from camp. Fred and Laurie arrived about 2000 hours, tired and hungry. Fed them goat stew and meat. Stayed up quite late around fire. Didn’t sleep good thinking about the grizzly.

George’s matter-of-fact writing style belies the intensity of this bear encounter. He had once related this story to me, describing with feeling how he was a good distance away from his hunting camp without his rifle, sitting beside a creek, when suddenly a grizzly bear appeared on a large rock only a few metres away. His written account understates the anxiety that he must have felt at the time, and that clearly lingered well into the night.

We put the tape aside as we neared our destination. Passing through the McGregor Mountains, we parked the truck on a side road below the Dezaiko Range of the Northern Rockies, and started our approach hike. Because of the early morning frost on the vegetation, we didn’t get too wet. After the first hour, we entered the mainly primordial forest on an old horse trail that had been built some thirty years earlier by guide outfitter Clarence Simmons.5 Once we were under the cover of the old trees, where the vegetation changes more slowly over time than in the open, our route became much more distinct. We arrived at a familiar stream crossing at the bottom of the gully that led up the mountain, and we each found a different way to cross according to our individual temperaments. George took the most direct route, moving with a sure foot over a slippery log. I can almost hear the words of his childhood mentor, his cousin Bob, admonishing him: “George, do not hesitate.” I gave the problem more thought, and hesitantly worked my way upstream over moss-covered rocks and woody debris to make a precarious crossing on slippery rocks. George’s temperament, born of experience and confidence in the outdoors, was to just go for it.

George’s patience in situations like this stood in stark contrast to the restless energy that he exhibited in almost everything else that he did. The first ski trips that I had done with him nearly eighteen years earlier were taken at a time when I was ill-equipped and inexperienced in steep terrain. He would sometimes wait for me for what must have seemed like hours to him as I struggled up or down the mountain. I often wondered where his patience came from. “Perhaps,” someone who knew him well once confided to me, “he’s worn out so many prospective hiking companions that he’s learned to be patient with those who remain.”

The trail climbed steeply up the ridgeline to the east of the gully, and we paused partway as a golden eagle sailed past us up the draw. The previous evening, I had dreamt of a golden eagle perched next to me as I sat with a companion on the edge of a steep gully or valley. The bird in the dream was brightly coloured, although these eagles are not; yet for some reason, in the hazy world of sleep, I knew it as a golden eagle. To the best of my recall, I had never dreamed of an eagle before, and I couldn’t remember a dream object being so vivid.

We continued climbing. For nearly twenty years, I had been writing for various publications, and for some time I had harboured the idea of writing a book. Several topics had eddied around, but nothing definite had settled out. As we climbed the mountain in the quiet, crisp morning air, a thought hit me with sudden clarity. My book would be a biography of this man I was travelling with. I was taken aback — where had that idea come from? This was not the first time I had a flash of insight on this route — another had occurred while climbing alone on a Friday evening, an hour away from a nine o’ clock rendezvous on the top of the mountain with George, who had hiked in earlier in the day. On that occasion I emerged from forest into alpine meadows, lost in a deep reverie as I climbed in the evening light, and suddenly I had a rare glimpse of life’s meaning. Now, as I watched George push through the wet rhododendron, both of us content with the rhythm of the climb, I began to sift through book ideas, wondering how I would broach the subject to this modest and private man. I decided to sleep on it and discuss it with George if the moment seemed right in the days ahead. Later, as with the chance recording of the bear debate and my dream about the eagle, I was to wonder at the manner and coincidence of the book’s genesis at this fateful time.

Stopping just below the treeline, George lit a fire to help us dry off while we ate lunch. As we continued the climb into the alpine meadows, there was now just enough snow to ski on, and my pack felt light and secure again. We travelled in a magical realm with clouds above and below us. The valleys glimpsed through breaks in the clouds now belonged to another world. Our route narrowed to a thin ridge overhanging a steep-sided valley, and we paused to savour the clear, cool air and to catch our breath.

Suddenly, another golden eagle soared from the valley and passed only a few metres away from us, closer to me than ever before. The white markings on its wings and tail feathers identified it as immature, but it was followed a moment later by a mature companion that was a little farther out. I was so struck by the vivid manifestations of my dream of the night before, and the enigmatic implications of the eagles, that immediately after returning to town I went to the public library and took out every book I could find on dream interpretation. They didn’t provide an answer, but I had a sense that a meaning would become clear. In belief systems such as shamanism and the Australian Aboriginal dreamtime, there are clues to our existence and our relationship with the world around us beyond those that are apparent in our waking lives. According to these ideas, which appear in many forms in various spiritual traditions, it is only at certain times or in certain places, or in special frames of mind that we are receptive.

We resumed our climb, at last reaching the high point of the approach hike. All my doubts about coming on the trip had long since fallen away, and we gazed down the snowy bowl to the lodge. Its metal roof and red-stained walls stood out in the midst of a small clump of trees far below us. Unfortunately our plans to ski down to the lodge in style evaporated as we saw that the slope had countless rocks sticking out, meaning that it would be a slow and treacherous descent. I opted to keep climbing skins on my skis, and take wide, slow traverses. Climbing skins attach to the base of backcountry skis to allow skiers to climb in steep terrain without slipping backward. Skis were almost natural appendages to George, and he took his skins off and went straight down the middle; in doing so, he had to take many necessary falls to avoid hitting the boulders that were everywhere. For the first time in my life, I stood at the bottom of a ski slope and waited for him to catch up.

The weather was pleasant during our two-day stay at the lodge, and we enjoyed the time that we spent touring and looking for wildlife. Apart from a few caribou tracks and the body of a rodent that had been mysteriously dropped onto an otherwise empty expanse of snow by a bird of prey, perhaps one of the numinous eagles, there wasn’t much to see. The absence of grizzly bear tracks suggested that the season had sufficiently advanced for them to be in their winter dens, an observation that made the events of two weeks later even harder to comprehend. The small amount of snow covering the rocks made it dangerous to ski downhill without the braking action of climbing skins. So again, I kept mine on and had a couple of slow runs. To George, it was unthinkable to ski down a mountain with skins on, just as he had steadfastly refused to snowshoe in the mountains with me over the years — it was ski or nothing. So on our excursion from the lodge on Sunday, he chose the latter and walked back down the slope carrying his skis, and for the second time in our twenty-year association, I waited for him at the bottom of a snow slope.

On Sunday evening in the lodge, I was reading one of George’s favourite books, Memoirs of a Mountain Man by Andy Russell. Three weeks later, I telephoned Andy Russell, then in his early eighties, to try and locate a passage that George had liked in one of Russell’s books to read at George’s memorial service. During my short telephone conversation with this man, an icon of western Canadian outdoor literature, a respected lifelong conservationist, and a 1977 recipient of the Order of Canada, I found him to be interested in George and the manner of his passing. He shared with me his thoughts about what might have happened on the Bearpaw Ridge, based on his own experience with grizzly bears gained over a lifetime spent in the mountains. I had read one of his best-known books, Grizzly Country, soon after moving to Prince George twenty years earlier. Andy Russell wondered if wolves might have killed the moose, which had then been claimed by the bear; a circumstance, he said, that could have made the situation far more dangerous as the bear would be more protective of the kill. A conservation officer who attended the scene later told me that he found the idea interesting. Andy Russell had turned away from guiding big-game hunting in the mountains to concentrate his talents on conservation and education, and his writing about this may have helped influence George Evanoff to do likewise.

George was his usual restless self as I tried to read from Andy Russell’s book. As usual, he was busy with activity, a habit that inevitably rubbed off on any companion who happened to be within range. I asked him if I could read aloud from a few passages that had caught my interest, and this gave George a reason to sit down for a few moments. It also created an opportunity to broach my book idea. Knowing how much he disliked self-aggrandizement, I voiced the notion with much trepidation. His first reaction was surprise rather than dismissal.

Sensing the opening, I pushed on with my thoughts about a book that would inspire others to discover and to experience the mountain backcountry as he had. To my surprise, George was warm to the idea, perhaps in part because of his connection to Norman Willmore. An address that Willmore gave to the Edson community in February 1955, a few months before he became Alberta’s minister of lands and forests, suggests the range of influence he might have had on the young Evanoff.6 Like Willmore, in his later years George was an entrepreneur and a mentor, who was involved in public land use planning and demonstrated great environmental sensitivity. While he was hiking in the Willmore Wilderness in 1997, a year before his death, George Evanoff had again remarked on his connection with Norman Willmore, and the impact that Willmore had on his life as a young man. George was sensitive to the effect that he, in turn, was now having on others.

It was beginning to snow as we started to ski out at first light on Monday morning. I had a sudden feeling of melancholy as I stood waiting in the meadow below the lodge watching George close the last shutters and install the porcupine defences on the doorstep to stop them from chewing the structure. I had watched him do this many times, but on this day I felt an inexplicable wave of sadness as if I was watching him close up the cabin for the last time. I wondered again where that emotion had come from. The feeling passed as we set out. George travelled on foot, deciding to leave his skis at the lodge with the intention of retrieving them during the first fly-in trip he planned to do in a few weeks time. He had unknowingly hung up his skis for the last time.

I climbed ahead of him, enjoying the advantage of skis at this stage of our journey. Later, the tables would be turned when we left the snow behind and I had to carry my skis. By the time we reached the summit, we were caught in an easterly blizzard and whiteout. The mountains were behaving predictably for departure time. My eyeglasses iced up and rendered me nearly blind. With hood up and head down, I followed the shadowy form of the sixty-six-year-old man, secure in his presence as he led us back to the green- and gold-coloured world below, where it wasn’t quite winter yet.

My first encounter with George Evanoff in early 1979 had begun a long association that was fun, often physically demanding, and always rewarding. Nearly twenty years later, during the Thanksgiving weekend of 1998, we talked in his mountain lodge and the seed that became this book was planted. To appreciate the real origins of his story, however, we must traverse half a world, and nearly a century back in time, to the Balkan state of Macedonia in the early twentieth century, and to rural Alberta of the 1920s and 1930s.