Читать книгу Sierra South - Mike White - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

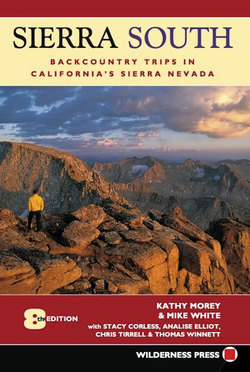

Welcome to what we think is just about the most spectacular mountain range in the contiguous 48 states. The Sierra Nevada is a hiker’s paradise filled with its hundreds of miles of wilderness uninterrupted by roads, hundreds of miles of trails, thousands of lakes, countless rugged peaks and canyons, vast forests, giant sequoias, and terrain ranging from deep, forested river valleys to sublime, treeless alpine country.

Updates for the Eighth Edition

Welcome, too, to the eighth edition of Wilderness Press’s Sierra South. For this edition, we have some new co-authors, and we’ve taken a radically different approach to organizing the trips. This book is divided first into the Sierra’s west and east sides and second, within the west and east sides, into road sections so you can easily locate your favorite part of the southern Sierra. Each road section includes trailheads that serve as starting points for the many individual trips in the book. Additionally, each trailhead includes a map showing every trip launching from that point, and each trip includes an elevation profile. We’ve also incorporated Global Positioning System (GPS) data as UTM coordinates into our trips for GPS users. We think these changes reflect the way in which you’ll actually use this book better than previous editions have.

Sierra South now spans the Sierra from the southern boundary of Yosemite National Park and from Yosemite’s eastern boundary south of Hwy. 120 (the Tioga Road) to the Sherman Pass area, covering a greater north-south region than previous editions. This region includes the true High Sierra, with its abundance of dramatic, above-treeline granite peaks and basins. As of its ninth edition, this book’s sister, Sierra North, covers the Sierra from Yosemite north through the Tahoe area to I-80 and the proposed Castle Peak Wilderness just north of I-80.

Unlike the region covered by Sierra North, in the territory this book covers, no roads cross the range between Hwy. 120 on the north and the network of roads that cross Sherman Pass, a distance of some 140 air miles to the south. However, along those 140 air miles, many roads penetrate the range from its west and east sides, and these are the roads you’ll use to get to trailheads in this book. The book’s first major trip section covers the region’s west side and presents roads into the west side from north to south. The second major trip section covers the Sierra’s east side and, also from north to south, the roads into the range from the east.

If you have used previous editions of Sierra South, you’ll find many of your old favorite trips here, as well as some wonderful new ones. Our coverage now includes Dinkey Lakes, Kaiser, and Jennie Lakes wildernesses, in addition to Ansel Adams, John Muir, and Golden Trout wildernesses. Most longer trips can be abbreviated to create fine, shorter ones, and many can be linked to other trips to create multiweek adventures. As before, this edition includes the must-see High Sierra Trail (now Trip 31).

It’s our hope that this new edition will help you enjoy our superb southern Sierra as well as give you an incentive to work to preserve it.

We appreciate hearing from our readers. One of our goals is to keep improving these books for you. Please let us know what did and didn’t work for you in this new edition and about changes you find. We’re at 1200 5th St., Berkeley, CA 94710; mail@wildernesspress.com; 800-443-7227; 510-558-1666; fax 510-558-1696. Please visit us online at www.wildernesspress.com.

Care and Enjoyment of the Mountains

Be a Good Guest

The Sierra is home—the only home—to a spectacular array of plants and animals. We humans are merely guests—uninvited ones at that. Be a careful, considerate guest in this grandest of Nature’s homes.

About a million people camp in the Sierra wilderness each year. The vast majority of us cares about the wilderness and tries to protect it, but it is threatened by some who still need to learn the art of living lightly on the land. The solution depends on each of us. We can minimize our impact. The saying, “Take only memories (or photos), leave only footprints,” sums it up.

Learn to Go Light

John Muir, traveling along the crest of the Sierra in the 1870s with little more that his overcoat and his pockets full of biscuits was the archetype.

Muir’s example may be too extreme for many, but we think he might have appreciated modern lightweight equipment and food as a great convenience. A lot of the stuff that goes into the mountains is burdensome, harmful to the wilderness, or just plain annoying to other people seeking peace and solitude. Please leave behind anything that is obtrusive or that can be used to modify the terrain: gas lanterns, radios, hatchets, gigantic tents, etc.

Carry Out Your Trash

You packed that foil and those cans and bags in when full; you can pack them out empty. Never litter or bury your trash.

Sanitation

Eliminate body wastes at least 100 feet, and preferably 200 feet, from lakes, streams, trails, and campsites. Bury feces at least 6 inches deep wherever possible. Intestinal pathogens can survive for years in feces when they’re buried, but burial reduces the chances that critters will come in contact with them and carry pathogens into the water. Where burial is not possible due to lack of enough soil or gravel, leave feces where they will receive maximum exposure to heat and sunlight to hasten the destruction of pathogens. Also help reduce the waste problem in the backcountry by packing out your used toilet paper, facial tissues, tampons, sanitary napkins, and diapers. It’s easy to carry them out in a heavy-duty, self-sealing plastic bag.

Protect the Water

Just because something is “biodegradable,” like some soaps, doesn’t mean it’s okay to put it in the water. In addition, the fragile sod of meadows, lakeshores, and streamsides is rapidly disappearing from the High Sierra. Pick “hard” campsites, sandy places that can stand the use. Camp at least 200 feet from water unless that’s absolutely impossible; in no case camp closer than 25 feet. Don’t make campsite “improvements” like rock walls, bough beds, new fireplaces, or tent ditches.

Avoid Campfires

Use a modern, lightweight backpacking stove. (If you use a gas-cartridge stove, be sure to pack your used cartridges out.) Campfires waste a precious resource: wood that would otherwise shelter animals and, upon falling and decaying, return vital nutrients to the soil. Campfires also run the risk of starting forest fires.

Exercise special care when using an ultra-lightweight alcohol stove, as its flames tend to be uncontrollable when the pot is off the burning stove. Be sure the area is cleared for at least a cubic yard of flammable materials above, around, and below the stove.

If your stove fails and you must cook over a campfire in order to survive, here are some guidelines: If possible, camp in an established site with an existing fireplace you can use. If you must build a fireplace, build with efficiency and restoration in mind: two to four medium-sized rocks set parallel along the sides of a narrow, shallow trench in a sandy place. Set the pot on the rocks and over the fire, which you can feed with small sticks and twigs (use only dead and downed wood). Never leave the fire unattended. Before you leave, thoroughly extinguish the fire and pour water over the ashes, and then restore the site by scattering the rocks and filling the trench.

To use a stove or have a campfire where legal, you must have a California Campfire Permit. One such permit is good for the season. Your wilderness permit can double as your California Campfire Permit. If you’re taking a trip that doesn’t require a wilderness permit, you still need a California Campfire Permit, available at any ranger station.

Respect the Wildlife

Avoid trampling on nests, burrows, or other homes of animals. Observe all fishing limits and keep shorelines clean and clear of litter. If angling, use biodegradable line and never leave any of it behind. If you come across an animal, just quietly observe it. Above all, don’t go near any nesting animals and their young. Get “close” with binoculars or telephoto lenses.

Deer

Grouse

Safety and Well Being

Hiking in the high country is far safer than driving to the mountains, and a few precautions can shield you from most of the discomforts and dangers that could threaten you.

Health Hazards

Altitude Sickness: If you normally live at sea level and come to the Sierra to hike, it may take your body several days to acclimate. Starved of your accustomed oxygen, for a few days you may experience shortness of breath even with minimal activity, severe headaches, or nausea. The best solutions are to spend time at altitude before you begin your hike and to plan a very easy first day. On your hike, light, frequent meals are best.

Giardia and Cryptosporidium: Giardiasis is a serious gastrointestinal disease caused by a waterborne protozoan, Giardia lamblia. Any mammal (including humans) can become infected. It will then excrete live giardia in its feces, from which the protozoan can get into even the most remote sources of water, such as a stream issuing from a glacier. Giardia can survive in snow through the winter and in cold water as a cyst resistant to the usual chemical treatments. Giardiasis can be contracted by drinking untreated water. Symptoms appear two to three weeks after exposure.

Cryptosporidium is another, smaller, very hardy pest that causes a disease similar to giardiasis. It’s been found in the streams of the San Gabriel Mountains of Los Angeles, and it is spreading throughout Southern California. Probably it will eventually infest Sierra waters.

At this time, boiling and filtering are the only sure backcountry defenses against giardia and cryptosporidium. Bring water to a rolling boil; this is easy to do while you’re cooking and is now judged effective at any Sierra altitude. To be effective against both giardia and the much-smaller cryptosporidium, a filter must trap particles down to 0.4 micron.

Halogen treatments (iodine, chlorine) are ineffective against cryptosporidium and hard to use properly against giardia—but they are better than no treatment at all. There are chlorine-dioxide water treatments available for backpackers as well as a device that claims to zap the bugs. The chlorine-dioxide treatments reportedly take 30 minutes to kill giardia and four hours to kill cryptosporidia. Consider these treatments as back-up systems—to use only when boiling or filtering isn’t possible; use only as directed.

This may feel cool and refreshing, but it’s advisable to filter or boil water before drinking it.

Hypothermia: Hypothermia refers to subnormal body temperature. More hikers die from hypothermia than from any other single cause. Caused by exposure to cold, often intensified by wet, wind, and weariness, the first symptoms of hypothermia are uncontrollable shivering and imperfect motor coordination. These are rapidly followed by loss of judgment, so that you yourself cannot make the decisions to protect your own life. Death by “exposure” is death by hypothermia.

To prevent hypothermia, stay warm: Carry wind- and rain-protective clothing, and put it on as soon as you feel chilly. Stay dry: Carry or wear wool or a suitable synthetic (not cotton) against your skin, and bring raingear, even for a short hike on an apparently sunny day. If weather conditions threaten and you are inadequately prepared, flee or hunker down.

Treat shivering at once: Get the victim out of the wind and wet, replace all wet clothes with dry ones, put him or her in a sleeping bag, and give him or her warm drinks. If the shivering is severe and accompanied by other symptoms, strip him or her and yourself (and a third party if possible), and warm him or her with your own bodies, tightly wrapped in a dry sleeping bag.

Lightning: Although the odds of being struck are very small, almost everyone who goes to the mountains thinks about it. If a thunderstorm comes upon you, avoid exposed places—mountain peaks, mountain ridges, open fields, a boat on a lake—and also avoid small caves and rock overhangs. The safest place is an opening or a clump of small trees in a forest.

The best body stance is one that minimizes the area your body touches the ground. You should drop to your knees and put your hands on your knees. This is because the more area your body covers, the more chance that ground currents will pass through it. Also make sure to get all metal—such as frame packs, tent poles, etc.—away from you.

If you get struck by lightning, there isn’t much you can do except pray that someone in your party is adept at CPR—or at least adept at artificial respiration if your breathing has stopped but not your heart. It may take hours for a victim to resume breathing on his or her own. If your companions are victims, attend first to those who are not moving. Those who are rolling around and moaning are at least breathing. Finally, a victim who lives should be evacuated to a hospital, because other problems often develop in lightning victims.

Wildlife Hazards

Rattlesnakes: They occur at lower elevations (they are rarely seen above 7000 feet but have been seen up to 9000 feet) in a range of habitats, but most commonly near riverbeds and streams. Their bite is rarely fatal to an adult, but a bite that carries venom may still cause extensive tissue damage.

If you are bitten, get to a hospital as soon as possible. There is no substitute for proper medical treatment.

Some people carry a snakebite kit such as Sawyer’s extractor when traveling in remote areas far from help and where snake encounters are more likely: below 6000 feet along a watercourse. This kit is somewhat effective if used properly within 30 minutes after the bite—but it’s still no substitute for hospital care.

Better yet, don’t get bitten: Watch where you place your hands and feet; listen for the rattle. If you hear a snake rattle, stand still long enough to determine where it is, then leave in the opposite direction.

Marmot

Rodents and Birds: Marmots live from about 6000 feet to 11,500 feet. Because they are curious, always hungry, and like to sun themselves on rocks in full view, you are likely to see them. Marmots enjoy many foods you do, including cereal and candy (especially chocolate). They may eat through a pack or tent when other entry is difficult. Marmots cannot climb trees or ropes, so you can protect your food by hanging it (though this is illegal in some areas because of bears). Smaller, climbing rodents might get into hung food. We’ve heard reports of jays pecking their way into bags, too. Sealed bear canisters are excellent protection against all kinds of rodents, birds, and insects. (Please see for information about bears.)

Mosquitoes: Insect repellent containing N, N diethylmeta-toluamide, known commercially as deet, will keep them off. Don’t buy one without a minimum of about 30% deet. Studies show adults can use deet in moderation, but it is dangerous for children. To minimize the amount of deet on your skin, apply it to your clothes and/or hat instead—but test first to be sure that deet won’t damage the garment.

A newer, time-release deet preparation works well and is much less objectionable than straight deet; however, it may be more expensive. Try this if you can’t abide straight deet.

Most non-deet and low-deet repellents work much more poorly than those with 30% deet or more, and electronic repellents are useless. Clothing may also act as a bar to mosquitoes—a good reason for wearing long pants and a long-sleeved shirt. If you are a favorite target for mosquitoes (they have their preferences), you might take a head net—a hat with netting suspended all around the brim and a snug neckband.

A tent with mosquito netting makes a world of difference during mosquito season (typically, through late July). Planning your trip to avoid the height of the mosquito season is also a good preventive.

Terrain Hazards

Snow Bridges and Cornices: Stay off them.

Streams: In early season, when the snow is melting, crossing a river can be the most dangerous part of a backpack trip. Later, ordinary caution will see you across safely. If a river is running high, you should cross it only there is no safer alternative, you have found a suitable place to ford, and you use a rope—but don’t tie into it; just hold onto it.

Here are some suggestions for stream-crossing:

If a stream is dauntingly high or swift, forget it. Turn around and come back later, perhaps in late summer or early fall, when flows reach seasonal lows.

Wear closed-toe shoes, which will protect your feet from injury and give them more secure placement.

Cross in a stance in which you’re angled upstream. If you face downstream, the water pushing against the back of your knees could cause them to buckle.

Move one foot only when the other is firmly placed.

Keep your legs apart for a more stable stance. You’ll find a cross-footed stance unstable even in your own living room, much less in a Sierra torrent.

One or two hiking sticks will help keep you stable while crossing. You can also use a stick to probe ahead for holes and other obstacles that may be difficult to see and judge under running water.

One piece of advice used to be that you should unfasten your pack’s hip belt in case you fell in and had to jettison the pack. However, modern quick-release buckles probably make this precaution unnecessary. Keeping the hip belt fastened will keep the pack more stable, and this will, in turn, help your stability. You may wish, however, to unfasten the sternum strap so that you have only one buckle to worry about.

The Bear Problem

The bears of the Sierra are American black bears; their coats range from black to light brown. Unless provoked, they’re not usually aggressive, and their normal diet consists largely of plants. The suggestions in this section apply only to American black bears, not to the more aggressive grizzly bear, which is extinct in California.

American black bears run and climb faster than you ever will, they are immensely stronger, and they are very intelligent. Long ago, they learned to associate humans with easy sources of food. Now, keeping your food away from the local bears is a problem. Remember, though, that they aren’t interested in eating you. Don’t let the possibility of meeting a bear keep you out of the Sierra. Respect these magnificent creatures. Learn what you can do to keep yourself and your food safe. Some suggestions follow.

Bears—Any Time, Anywhere: You may encounter bears anywhere in the areas this book covers. If they present special problems on that trip, we mention them in the “Heads Up!” paragraph of that trip. Bears are normally daytime creatures, but they’ve learned that our supplies are easier to raid when we’re asleep, so they’re working the night shift, too. Also, it used to be that you rarely saw bears above 8000 to 9000 feet. As campers moved into the higher elevations, the bears followed.

To avoid bears while hiking, some people make noise as they go, because most American black bears are shy and will scramble off to avoid meeting you. Other people find noise-making intrusive, consider those who make noise rude, and accept the risk of meeting a bear. You will have to decide.

In camp, store your food properly and always scare bears away immediately. (See Food Storage.)

Plan Ahead: Avoid taking smelly foods and fragrant toiletries; they attract bears—bears have a superb sense of smell. Ask rangers and other backpackers where there are bear problems, and avoid those areas; also ask them what measures they take to safeguard food and chase bears away.

Carry a bear canister (see more below). If you need to counterbalance your food bags, practice the skill before you need it. After cooking, clean up food residue. Before going to sleep or leaving your camp, clean any food out of your gear and store it with the rest of your chow; otherwise, you could lose a pack to a bear that went for the granola bar you forgot in a side pocket. Don’t take food into your tent or sleeping bag unless you want ursine company. Store your smelly toiletries and garbage just as carefully as you store your food. Set up and use your kitchen at a good distance from the rest of your camp. Also make sure your food, even in canisters, is stored a good distance from your campsite.

Food Storage: Backcountry management policies now hold campers responsible for keeping their food away from bears. You can even be fined for violating food-storage rules. You’re also responsible for cleaning up the mess once you’re sure the bear won’t be back for seconds. And you have an ethical responsibility to keep bears from becoming pests, which may mean that they have to be killed.

Here are some food-storage suggestions that will help you do this:

Bear Canisters: The first ones were lengths of sturdy plastic pipe fitted with a bottom and a lid only a human can open. Today there are several more choices, including lighter-weight aluminum ones and still lighter ones of exotic aerospace materials. Using these canisters is the best method for protecting your food where bear boxes (below) aren’t available.Canisters aren’t perfect, but they work very well when used properly. Using a canister is much easier and more secure than counterbalance bearbagging. They make good in-camp seats, too.There’s also an extremely lightweight sack of bulletproof material, now available with an aluminum liner and with an odor-barrier inner sack. It is less secure than a canister, is slightly more difficult to use properly (but much easier than counterbalancing), and may not be approved for use in areas that require you to use a canister, like Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. You can check online or call the controlling agency(ies) to see if the areas through which you plan to pass permit use of these sacks. One of us has had good luck with them.The materials you receive with your permit will tell you whether canisters are required. If you don’t own a canister, you can rent one from either an outdoors store or perhaps from the agency that issues your permit.

Counterbalance Bearbagging: If you don’t have a bear-resistant food canister or access to a bear box where you camp, counterbalance your food. Note that in areas with severe bear problems, like most of Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks, counterbalance bearbagging is ineffective and probably against regulations.Assuming you’re traveling in an area where bears aren’t yet a severe problem, counterbalance bearbagging may protect your food not only from bears but from ground squirrels, marmots, and other creatures. It’s best to get to camp early enough to get your food hung while there’s light to do it. Counterbalancing is not completely secure, but it may slow the bear down. It gives you time to scare it away. When you get a permit, you may get a sheet on the counterbalance bearbagging technique. The technique is also well-covered in numerous how-to-backpack books. Practice it at home before you go.If a bear goes after your food, jump up and down, make a lot of noise, wave your arms—anything to make yourself seem huge, noisy, and scary. Have a stash of rocks to throw and throw them at trees and boulders to make more noise. Bang pots together. Blow whistles. The object is to scare the bear away. Never directly attack the bear itself. Note, however, that some human-habituated bears simply can’t be scared off.

Bear Boxes (Food Storage Lockers): Bear boxes are large steel lockers intended for storage of food only, and they will hold the food bags of several backpackers. Their latches, simple for humans, are inoperable by bears. Everyone shares the bear box; you may not put your own locks on one. Food in a properly fastened bear box is safe from bears; however, some boxes have holes in the bottom, through which, if the holes aren’t plugged, mice will squeeze in to nibble on your goodies.There are bear boxes at popular areas in Sequoia National Park and southern Kings Canyon National Park. Their locations and numbers, as well as regulations and a list of approved bear canisters, are available at or through links at www.nps.gov/seki/snrm/wildlife/food_storage.htm.The presence of a bear box attracts campers as well as bears, and campsites around them can become overused. However, it isn’t necessary for everyone to cluster right around the box. A campsite a few hundred yards away may be more secluded and desirable; the stroll to and from the bear box is a pleasant way to start and end a meal.Bear-box don’ts: Never use a bear box as a garbage can! Rotting food is smelly and very attractive to bears. Never use a bear box as a food drop; its capacity is needed for people actually camping in its vicinity. Never leave a bear box unlatched or open, even when people are around.

Above timberline: Up above the tree line, there are no trees to hang your food bags from. But there are still bears—as well as mice, marmots, and ground squirrels—anxious to share your chow. If you don’t have a canister or bulletproof sack (the latter only where legal) but must hang your food, look for a tall rock with an overhanging edge, from which you can dangle your food bags high off the ground and well away from the face of the rock. Unlike bears, marmots and other critters have not learned to get your food by eating through the rope suspending it.Another option is to bag your food and push it deep into a crack in the rocks too small and too deep for a bear to reach into—but be sure you can still retrieve it. One of us has had good luck with this technique; use it only above timberline. You may lose a little food to mice or ground squirrels, but it won’t be much.When dayhiking from a base camp where you can’t put your food in a bear box or leave it in a canister, it’s safer to take as much of it with you as you can.

If a Bear Gets Your Food: Never try to get your food back from a bear. It’s the bear’s food now, and the bear will defend it aggressively against puny you. You may hear that there are no recorded fatalities in bear-human encounters in recent Sierra history. Of course, this isn’t true: Plenty of bears have been killed as a result of repeated encounters. Every time a bear gets some human food, that bear is a step closer to becoming a nuisance bear that has to be killed. And there have been very serious, though not fatal, injuries to humans in these encounters.

If, despite your best efforts, you lose your food to a bear, it may be the end of your trip but not of the world. You won’t starve to death in the maximum three to four days it will take you to walk out from even the most remote Sierra spot. Your pack is now much lighter. And you can probably beg the occasional stick of jerky or handful of gorp from your fellow backpackers along the way. So cheer up, clean up the mess, get going, and plan how you can do it better on your next trip.

A Word About Cars, Theft, and Car Bears: Stealing from and vandalizing cars are becoming all too common at popular trailheads. You can’t ensure that your car and its contents will be safe, but you can increase the odds. Make your car unattractive to thieves and vandals by disabling your engine (your mechanic can show you how), hiding everything you leave in the car, and closing all windows and locking all doors and compartments. Get and use a locking gas-tank cap. If you have more than one car, use the most modest one for driving to the trailhead.

Bearproof your car by not leaving any food in it and by hiding anything that looks like a picnic cooler or other food carrier—bears know what to look for. To a bear, a car with food in it is just an oversized can waiting to be opened. Some trailheads have bear boxes. Leave any food and toiletries you’re not taking into the backcountry in these bear boxes rather than in your car.

The Regulations: Call, write to, or get on the website of the agency in charge of the area you plan to visit in order to learn the latest regulations, especially those concerning bears and food storage. For each trailhead in this book, you’ll find the agency’s name, physical address, phone number, and web address (if there is one) under Information and Permits.

Wilderness and Campfire Permits

In most places, everyone who travels overnight into a national park or national forest wilderness is required to carry a wilderness permit from the agency administering the starting trailhead. If your trip extends through more than one national forest or through both a national forest and a national park, get your permit from the forest or park where your trip starts.

A wilderness permit is issued for a single trip with a specific start date, for specific entry and exit points, and for a specified amount of time. Your permit is inflexible as to the trailhead entry point and start date. A separate permit is required for each trip. Group sizes and numbers of stock are usually restricted.

The permit system has a couple functions: The agencies responsible for the backcountry learn how many people and head of stock are using each trailhead, so they can make better decisions to prevent overuse of these areas. By giving out information with the permit on how to camp safely, avoid impact on the wilderness, and properly deal with bears, the agencies also educate wilderness users.

During the summer months, forest rangers patrol many backcountry trails, and they may ask to see your wilderness permit. If you do not have one, you may be fined and expelled from the backcountry.

There are two ways to get a permit: in person (on demand) and by advance reservation. Whether you plan to apply for your wilderness permit in advance or at the time of your trip in person, we strongly suggest you telephone the administering agency or check its website first. Rules, regulations, and procedures for issuing permits change fairly often. Further, weather, runoff conditions, and forest fires sometimes close trails in the backcountry; you can learn about this, too, in your telephone call or web research. Within each trailhead chapter, we identify the agency in charge and how to get in touch with them for more information.

HELPFUL WEBSITE

SierraNevadaWild.gov (http://sierranevadawild.gov/) is a user-friendly government source for backcountry trip planning in Sierra Nevada national parks, forests, and public lands. You’ll find a wealth of wilderness information here—some via links—for all established Sierra Nevada wilderness areas, though not for proposed wilderness additions and wilderness study areas.

On-Demand Permits

You can go in person for a permit to an agency location near your entry point the day before or on the day you plan to begin your trip. The national forests and the national parks maintain a number of conveniently located facilities to serve you. Because of the severe cutbacks in funding, however, the agencies don’t know from year to year which locations will be open during the summer season. Use the information provided in each trailhead section to find the visitor center, ranger station, or satellite most convenient for you.

Reserving Permits in Advance

You can also reserve a permit by mail (and sometimes by email, fax, or phone) up to six months in advance of your trip. Use the information provided in each trailhead section to discover how and when to apply.

If you apply for a permit reservation in advance:

Know whether a fee applies; if so, include payment in the appropriate form. By mail: Include a money order or check for that amount made payable to the US Department of Agriculture—Forest Service for Forest Service wilderness areas and to the National Park Service for Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks, or use a credit card. By fax or phone: Use a credit card. When using a credit card, supply the card type, number, and expiration date. Applications lacking the required fee will not be processed.

If applying by mail or fax, enclose or fax a completed wilderness permit application form, one for each trip, or write a letter containing the same information. If applying by phone, be ready to supply the same information. Some agencies’ websites have permit-application forms you can print out or download. If not, here is the information you need to supply: name, address, daytime phone, number of people in the party, method of travel (ski, snowshoe, foot, horse, etc.), number of stock (if applicable), start and end dates, entry and exit trailheads, principal destination, alternate dates and/or trailheads. You may also be asked for an itinerary.

Be sure to provide a second and even a third choice of trailhead and/or entry date, in case your first choice is not available.

If the agency will not mail your permit, find out where you should pick it up.

Quotas

For most trailheads, the agencies have set limits or quotas on the number of people who can enter a trailhead per day. Quotas are in effect mainly in the summer months; the time when they are in effect is called the quota period. Where quotas apply, only a limited number of advance reservations are accepted. The remainder of the quota is set aside for in-person applications, up to 24 hours in advance of your entry, on a first-come, first served basis.

If you plan to begin your trip from one of these trailheads, especially on the weekend, you would be wise to reserve your permit in advance. A reservation for a permit is not the same as the permit itself. Only a few agencies mail you the actual permit; most require that you pick up the permit near the trailhead entry. The purpose of the reservation is to guarantee you’ll get a permit for that trailhead on the day you wish. Where no quotas apply, the only reason to reserve your permit by mail is to allow you to pick it up during off hours.

Maps and Profiles

Today’s Sierra traveler is confronted by a bewildering array of maps, and it doesn’t take much experience to learn that no single map fulfills all needs. There are topographic maps, base maps (US Forest Service), shaded relief maps (National Park Service), artistically drawn representational maps (California Department of Fish and Game), aerial-photograph maps, geologic maps, three-dimensional relief maps, soil-vegetation maps, and compact discs containing five levels of topographic maps already pieced together for you as well as software for drawing routes. Each map has different information to impart, and it’s a good idea to use several of these maps in your planning.

For trip-planning purposes, the trailheads in this book include their own gray-scale map or maps, which show all trips and are based on the United States Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps or USDA Forest Service wilderness maps. (More information about these maps.)

A useful map series for planning is the USDA Forest Service topographic series for most individual wilderness areas. The scale of most maps of this series is 1:63,360 (1 inch = 1 mile), which is very close to that of the former USGS 15’ series (1:62,500), and each conveniently covers the entire wilderness area on one map. However, you may find these maps a bit bulky for the trail.

Most backpackers prefer to use a topographic (topo) map with finer detail than the above overview/planning maps. Hikers typically prefer the USGS 7.5’ series, where the elevation is usually shown in 40-foot contour intervals (although some 7.5’ topos show 80-foot contour intervals or even 20-meter contour intervals) and the scale is 1:24,000 or about 2.625 inches per mile.

Wilderness Press still publishes and regularly updates a few 15’ topos for some areas covered by Sierra South. These Wilderness Press 15’ topos include indexes of the place names on them and are printed on waterproof, tear-resistant plastic. If any one or more of these maps covers all or part of a given trip, their titles appear in boldface at the beginning of the trip under the section Topo. Unlike ordinary USGS topos, these maps show details of the adjacent national forest or park for your greater convenience in trip-planning. Wilderness Press still publishes the following 15’ quads that apply to Sierra South: Merced Peak, Devils Postpile, Mt. Abbott, and Mt. Pinchot.

You can also use commercially available software to print out your own topographic maps at your choice of scale and detail. Protect these printouts if the ink is prone to run.

How and Where to Get Your Maps

Order Wilderness Press 15’ topos and other maps as well as books directly from Wilderness Press online at www.wildernesspress.com or by phone at 800-443-7227.

Backpacking stores and some bookstores—especially those near popular hiking areas—carry at least the topographic maps for hikes in their areas as well as the software required to print your own. USGS topographic maps and US Forest Service maps are available at many ranger stations and at stations that issue wilderness permits.

USGS’s online store sells USGS maps at store.usgs.gov. Or contact the USGS Western Region office at 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025; 650-853-8300.

How to Use This Book

Terms This Book Uses

Destination/UTM Coordinates: This new edition provides UTM coordinates for GPS users. When the datum is from the field, we note this by including “(field)” after the datum. Otherwise, the datum is from mapping software. Because these data are all UTM data with the appropriate meters east (mE) and meters north (mN), we don’t repeat those labels but show UTM data in this form: 11S 395115 4034251.

Trip Type: This book classifies a trip as one of four types. An out-and-back trip goes out to a destination and returns the way it came. A loop trip goes out by one route and returns by another with relatively little or no retracing of the same trail. A semiloop trip has an out-and-back part and a loop part; the loop part may occur anywhere along the way, and if it’s in the middle, there are two out-and-back parts. A shuttle trip starts at one trailhead and ends at another; usually, the trailheads are too far apart for you to walk between them, so you will need to leave a car at the ending (take-out) trailhead, have someone pick you up there, or rely on California’s scanty and ill-organized public transportation to get back to your starting (put-in) trailhead.

Best Season: Deciding when in the year is the best time for a particular trip is a difficult task because of yearly variations. Low early-season temperatures and mountain shadows often keep some of the higher passes closed until well into August. Early snows have been known to whiten alpine country in late July and August. Some of the trips described here are low-country ones, offered specifically for the itchy hiker who, stiff from a winter’s inactivity, is searching for a warm-up excursion. These trips are labeled early, a period that extends roughly from late May to early July. Mid is from early July to the end of August, and late is from then to early October.

Pace: For each trip, we give the number of days you’d spend hiking at the trip’s described pace—leisurely, moderate, or strenuous—as well as the number of layover days (below) you might want to take. Since this book is written for the average backpacker, we chose to describe most trips on either a leisurely or a moderate basis, depending on where the best overnight camping places were along the route. We call a few trips strenuous. A leisurely pace lets hikers absorb more of the sights, smells, and “feel” of the country they have come to see.

Layover Days: These are days when you’ll want to remain camped at a particular site so you can dayhike to see other beautiful places around the area or enjoy some adventures like peakbagging. The number of layover days you take and where are purely personal choices, to be balanced with how much time you have and how much food you can carry. Our trip descriptions will help you pick where and when you want to take layover days.

Total Mileage: The trips in this book range in length between 5 and 110 miles, and many trips can be shortened or extended, based on your interest and time.

Measuring distances in the backcountry is more an art than a science. We use decimal fractions for indicating distances, but don’t imagine that we measured them to the tenths and hundredths of miles. The numbers represent our best estimates of distance based on techniques like the time it took us to get from point to point. You can’t represent thirds accurately as decimal fractions, so we use 0.3 for one third and 0.6 for two thirds.

Campsites: Campsites are labeled poor, fair, good, excellent, or, occasionally, Spartan, which usually means an above-timberline site with few amenities, much exposure, and breathtaking scenery. The criteria for assigning these labels were amount of use, immediate surroundings, general scenery, presence of vandalism, availability of water, kind of ground cover, and recreational potential—angling, side trips, swimming, etc. Camping is forbidden on meadows and other vegetated areas and within a certain distance of any stream or lake. You will be informed of these rules for your areas when you get your wilderness permit. “Packer campsite” indicates a semi-permanent camp (usually constructed by packers for the “comfort of their clients”) characterized by things like nailed-plank table or benches, nails in the surrounding trees, and/or a large, rock fireplace.

Be careful to oberve all camping and fishing regulations.

Fishing: Angling, for many, is a prime consideration when planning a trip. While we note the quality of fishing throughout the book, experienced anglers know that the size of their catch relates not only to quantity, type, and general size of the fishery, which are given, but also to water temperature, feed, angling skill, and that indefinable something known as “fisherman’s luck.” Generally speaking, the old “early and late” adage holds: Fishing is better early and late in the day, and early and late in the season.

Stream Crossings: Stream crossings vary greatly depending on snow-melt conditions. Often, June’s raging torrent becomes September’s placid creek. If a ford is described as “difficult in early season,” fording that creek may be difficult because it is hard to walk through deep or fast water, and getting caught in the current would be dangerous. Whether you attempt such a crossing depends on the presence or absence of logs or other bridges, downstream rapids or waterfalls, your ability and equipment, and your judgment. We mention manmade bridges and other manmade aids for you to cross on, but we usually don’t mention chance aids like logs and rocks, because they can vary from year to year. (See for tips for crossing streams more safely.)

Trail Type and Surface: Most of the trails described here are well maintained (the exceptions are noted) and are properly signed. If the trail becomes indistinct, look for blazes (peeled bark at eye level on trees) or ducks (two or more rocks piled one atop another). Trails may fade out in wet areas like meadows, and you may have to scout around to find where they resume. Continuing in the direction you were going when the trail faded out is often, but not always, a good bet.

Two other significant trail conditions have also been described in the text: the degree of openness (type and degree of forest cover, if any, or else “meadow,” “brush,” or whatever) and underfooting (talus, scree, pumice, sand, “duff”—a deep humus ground cover of rotting vegetation—or other material).

A “use trail” is an unmaintained, unofficial trail that is more or less easy to follow because it is well worn by use. For example, nearly every Sierra lakeshore has a use trail worn around it by anglers in search of their prey.

Landmarks: The text contains occasional references to points, peaks, and other landmarks. These places are shown on the appropriate topographic maps cited at the beginning of the trip. For example, “Point 9426” in the text would refer to a point designated simply “9426” on the map itself.

Fire Damage: The Forest Service and the Park Service have a policy of letting fires in the backcountry burn as long as they are not a threat to people or structures. One result has been some pretty poor-looking scenery on some trips in this book. However, most of the fire-damaged areas have begun to recover soon enough that we have chosen not to delete the affected trips from the book.

How This Book Is Organized

Trips in this book are organized according to the roads and highways you must drive to get to the trailheads in this book. Unlike the region covered in Sierra North, no road crosses the range south of Hwy. 120 for about 140 miles to the road that goes over Sherman Pass far to the south. Rather, in this region, roads penetrate the range from the west and from the east without crossing the range. Therefore, Sierra South is organized first by which side of the Sierra you must start on (west or east) and then, in north to south order, by the roads you must take into the range to get to the trailheads. The trailheads appear in the order you’ll find them as you drive into the range on that road.

Trailhead and Trip Organization: As previously noted, each trip is located within trailhead sections in the book. Those sections begin with a summary table, such as the fictitious one below, that uses the trailhead’s name, elevation, and UTM coordinates as its title. The table briefly summarizes each trip from this trailhead:

Black Powder Trailhead 7654’; 11S 736921 4328622

Following the table are details about information, permits, and driving directions to that trailhead.

Next comes the first trip from this trailhead. The trip data—UTM coordinates, total mileage, and hiking/layover days—are included with each trip entry. All trips include an elevation profile, a list of maps, and highlights. Some include HEADS UP!, or special considerations for that trip, and shuttle trips include directions to the take-out trailhead.

1 Bear Corral

Trip Data: 11S 735694 4338773; 18 miles; 2/1 days

Topos: Pickle Springs

Highlights: Follow a pair of delightful streams to a secluded basin rimmed by granite cliffs on the eastern fringe of XYZ Wilderness.

DAY 1 (Black Powder Trailhead to Bear Corral, 9 miles): From the trailhead, make a short climb northeast through a canopy of lodgepole, red fir, and white fir. Birds are abundant here, especially Steller’s jays, white-crowned sparrows, juncos, and chickadees. Soon the route reaches a junction with the PCT. Turn right (east) here and….

…to the good camping at forested Bear Corral (7654’; 11S 735694 4338773).

DAY 2 (Bear Corral to Black Powder Trailhead, 9 miles): Retrace your steps.

After this comes the next trip, if any, from this same trailhead. Trips in the same general area, especially multiple trips from the same trailhead, often build upon each other. For example, the first trip from a trailhead is usually the shortest—one day out to a destination, the next day back to the trailhead. The second trip will build on—extend—the first trip by following the first trip’s first day and then continuing on a second and subsequent days to more distant destinations. Rather than repeat the full, detailed description for the first trip’s first day, we recapitulate it as briefly as possible with the essential trail instructions to get you to that day’s destination. We also identify this as a recapitulation and give you a reference to the trip and day we’re recapitulating, like this: (Recap: Trip 1, Day 1.). If you wish, you can turn to that description to read everything we have to say about that day, which includes details about natural and human history—things that are fun to know but not essential for getting from the trailhead to the destination.

Trailhead Maps: Each trailhead section includes a map such as the one below. The legend that follows defines the symbols used in the maps in the book.

Great Western Divide from a rest stop at Panther Gap (Trip 30)