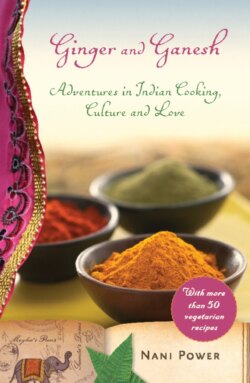

Читать книгу Ginger and Ganesh - Nani Power - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWaiting for Ganesh

A girl looks for spices. A woman finds them, and meets an Elephant God

I’VE BEEN PASSIONATELY in love with Indian cooking for thirty years—ever since I was in my teens and an older gentleman, a friend of the family, a world raconteur, took me to Georgetown to a white tablecloth affair in a raj-like atmosphere, with sitar-playing musicians and turbaned waiters. Of course, I was enchanted by this, but it was the arrival of a swamp-green bowl of coriander chutney that blew me away (back then, in the ’70s, we called it “coriander,” which of course I had never seen as this was the pre-cilantro era). Oh, try this, said my friend who had been many times to India. The spicy yet soapy taste intoxicated and mystified me. I was hooked. A large elephant-headed deity stood at the doorway, festooned with flowers, sprinkled with turmeric, surrounded by burning incense. What is that? I asked innocently.

That, my friend said, is Lord Ganesh. You don’t know Ganesh?

I was eighteen. No, I didn’t know Ganesh. I knew a small, stone Episcopal Church in my tiny town of Delaplane, Virginia, that had a large simple brass cross on the altar, where we attended after my mother remarried. I knew my deeply Catholic grandfather on my father’s side and the velvet-cloaked altar in his house, with a carved crucifix inside of Jesus in thorns. I knew a golden Buddha my mother kept in a small altar in our house, with a flower tucked inside, being the daughter in a foreign service family and having lived for years in Thailand. All these cross-cultural connections led to a mishmash of thoughts, but no clear direction. But this? His wise-appearing eyes shone out. He had the body of a man, with a large stomach. It was sensual, and assaulting—half man, half elephant, yet strangely comforting.

Thank him, my friend suggested.

I did.

He is the remover of obstacles, he said. Very important.

I FORGOT ABOUT Ganesh for some time, but not about Indian food: a suburban foray into the strip malls of Virginia found Indian Spices and Appliances, where I stocked up on all sorts of cookbooks (usually self-published paperbacks with bad, blurry color reproductions, written by Mrs. So-and-So), jumbo bags of spices (apparently one couldn’t buy simply a small jar of turmeric, one had to buy a crate of the stuff, which lasts forever), and various implements, of which I knew not how to use. Compare this to the spice department in your local grocery store: tiny jars containing a few tablespoons of curry powder, usually old and stale, selling for exorbitant prices.

During this time, I studied cookbooks and tried to re-create the dark, fairly unctuous-tasting, mysterious stews I found in Indian restaurants. I hadn’t tried Indian home-cooking—I thought what I was eating in restaurants was the norm. Little did I know!

I puttered around for years, trying all forms of vindaloos, curries, puffs, chutneys, but nothing tasted really good. My curries were watery, full of raw spice. My chutneys, overly gingered or bland. But a quest for wondrous food by reading cookbooks only goes so far: life is an experiential teacher. I remembered the smell of the incense and the statue of Ganesh: as a young woman, I was deeply attracted to the idea of God and spirituality, yet I had been subjected only to church, which I found insufferably boring, tedious, fake, and worst of all, it always smelled bad. I realize now the aura of ritual was missing, which even at my young age, spoke little of joy or ceremony. Hymns seemed heavy and ponderous to me. Still, I sensed that truth lay in all the religious texts, so I read them, anything I could get my hands on. I found the true teachings of Christ beautiful, love-filled, and thoughtful—I just didn’t like the vehicle. For years, I attended a Unitarian church in New York to get my spiritual fix, but found it had the same pared down lack of wonder as the others.

I went to Brazil and was intrigued by the Candomblé rituals I saw on the beaches, where followers left burning candles. One walked out the door at a fashionable restaurant at the heavily trafficked crossroads in Ipanema, only to almost walk into sacrificed chickens. Walking on the beach late one night, I witnessed such a ritual. A woman was possessed by Oxum, Goddess of love, beauty, fertility, and wealth. As the others drummed, the woman danced in a frenzy, laughing around a fire built on the sand. She cackled and sang. And then she saw me, and came forward, a jar of honey in her hand, enticing me to eat it, as she scooped up a spoonful. I was about to go to her—I was enchanted—when I was stopped by a harsh No from the priest, who pulled her away. You are not ready for this, he said. Of course not, I was in formation. My friends explained that I hadn’t been protected, that I needed to know the essence of the Candomblé to accept the gift, that it could be dangerous to my spirit. Nevertheless, it probably was dangerous to my spirit anyway: it left me hungry and searching for more. The thought that somewhere, beyond these soft and gentle suburban hills, there existed something alive and pulsing: in the food, in the rituals. Be it Brazil or Africa, Costa Rica or Nepal, it existed. And India seemed to call to me personally.

JUMP AHEAD FIFTEEN years: I am married, pregnant, have a three-year-old son, and live in Brooklyn. Fortunately my son has an Indian play-mate, a son of two doctors, and the two boys and his nanny and I hang out together, a woman from Kerala, in Southern India. Lo and behold, I am swept away again—entranced by the southern delights of idli cakes and dosas, coconut chutneys and curry leaves. Stella kindly teaches me a few dishes—which become cupboard standards for me. This is my first time encountering real home-cooked dal, which tastes like heaven, flecked with mustard seeds and curry leaves, as is the southern tradition, as opposed to the mud-like porridge generally served in restaurants. Finally, I know what my taste buds have been craving all these years.

We moved away from Brooklyn, after my few months of initiation into the rites of dal and dosas, and years passed by, with nary an Indian flavor, save an occasional buffet here and there or frozen samosas. A divorce followed and a long period of adjustment. Much food was cooked between catering and feeding my sons, heralding the holidays or just simple, comfort fare, but very few Indian dishes passed through our kitchen. No one seemed to share my passion, especially my two little boys who only wanted the simplest nibbles. But after some time, the lion of my spice cravings reared its head once more and I took charge, eschewing the books this time.

It hit me. Why couldn’t I learn from another Stella? Where was Stella? (I never found her again. She went back to India.) In desperation, I put out the ad. It was almost like I was searching for connection as well as good food. Who would’ve guessed that I would find culture, as well? Or even love? Yes, not only was my appetite for real Indian food reawakened in the home kitchens of my Indian neighbors, but my heart was reawakened—after a long, cold spell after divorce—by a love affair with a man who hails from India. Through the process of cooking in these homes, I also found a new spiritual partner, someone I’ll call “V,” a man I could discuss all my interests with, without deities or dogma, an exploration of the consciousness of one’s self. I went looking for Ginger and I found Ganesh. The musings of my palate led me to the cravings of my heart.

I see a small statue of Ganesh in an Indian store, staring at me with his doleful eyes.

I buy it. I buy incense. I start thanking him and ask him to clear obstacles, to bless my creativity. I read Ganesh likes bananas and I give him one occasionally.

Slowly, the obstacles fell away on this journey, and the doors flew open, leading me into a path of discovery, love, and coconut chutney.